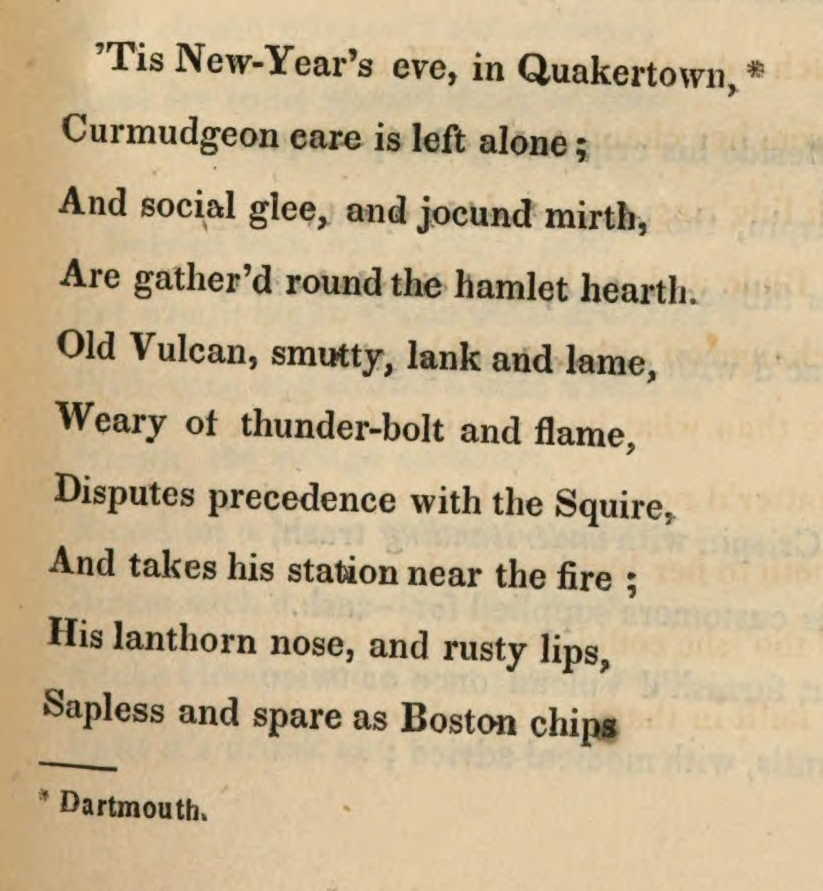

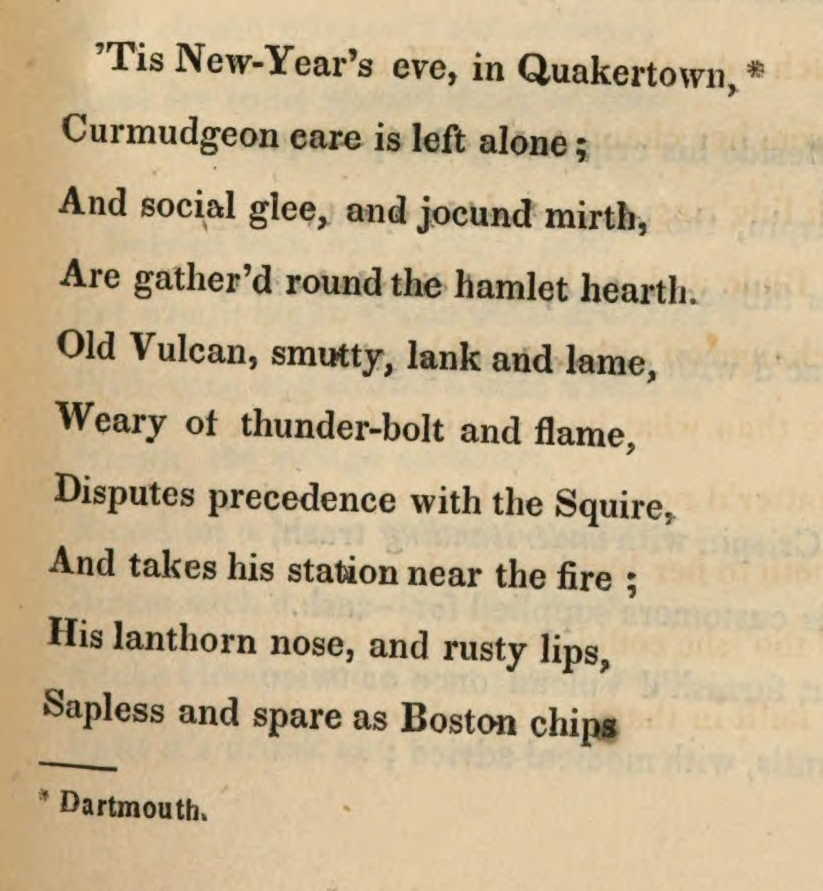

“‘Tis New-Year’s eve, in Quakertown (Dartmouth)”

Shiels, Andrew. The Witch of the Westcot: a Tale of Nova-Scotia, In Three Cantos; And Other Waste Leaves of Literature. Halifax: J. Howe, 1831. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433074874946

Amicitia Crescimus

“‘Tis New-Year’s eve, in Quakertown (Dartmouth)”

Shiels, Andrew. The Witch of the Westcot: a Tale of Nova-Scotia, In Three Cantos; And Other Waste Leaves of Literature. Halifax: J. Howe, 1831. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433074874946

“Rhode Islanders emigrating to Nova Scotia? How is that? …Ah Yes! They must have been a group of Tories… No! The colony of which I speak left the parent stock when all were alike loyal to the sovereign of Great Britain – indeed at just the juncture when it was the proudest boast of every New Englander that he was a British subject.

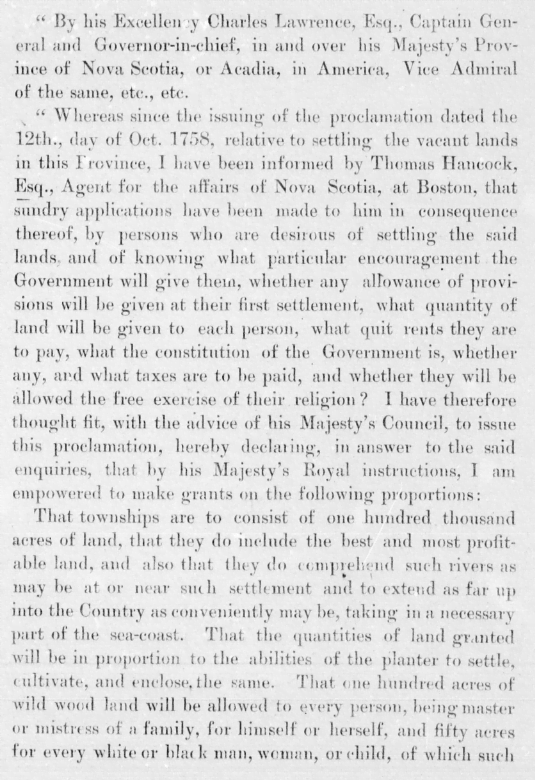

Jan. 11, 1759, Governor Lawrence sent forth from the Council Chamber at Halifax, a second proclamation:

“By his Excellency Charles Lawrence, Esq., Captain General and Governor-in-chief, in and over his Majesty’s Province of Nova Scotia, or Acadia, in America, Vice Admiral of the same etc. etc.

“Whereas since the issuing of the proclamation dated the 12th., day of Oct. 1758, relative to settling the vacant lands in this Province, I have been informed by Thomas Hancock, Esq., Agent for the affairs of Nova Scotia, at Boston, that sundry applications have been made to him in consequence thereof, by persons who are desirous of settling the said lands, and of knowing what particular encouragement the Government will give them, whether any allowance of provisions will be given at their first settlement, what quantity of land will be given to each person, what quit rents they are to pay, what the constitution of Government is, whether any, and what taxes are to be paid, and whether they will be allowed the free exercise of religion? I have therefore thought fit, with the advice of his Majesty’s Council, to issue this proclamation, hereby declaring, in answer to the said enquiries, that by his Majesty’s Royal instructions, I am empowered to make grants on the following proportions:

That townships are to consist of one hundred thousand acres of land, that they do include the best and most profitable land, and also that they do comprehend such rivers as may be at or near such settlement and to extend as far up into the Country as conveniently may be, taking in a necessary part of the sea-coast. That the quantities of land granted will be in proportion to the abilities of the planter to settle, cultivate, and enclose, the same. That one hundred acres of wild wood land will be allowed to every person, being master or mistress of a family, for himself or herself, and fifty acres for every white or black man, woman, or child, of which such person’s family shall consist at the actual time of making the grant, subject to the payment of a quit rent of one shilling sterling per annum for every fifty acres; such quit rent to commence at the expiration of ten years from the date of each grant, and to be paid for his Majesty’s use to his receiver General, at Halifax, or to his Deputy on the spot.

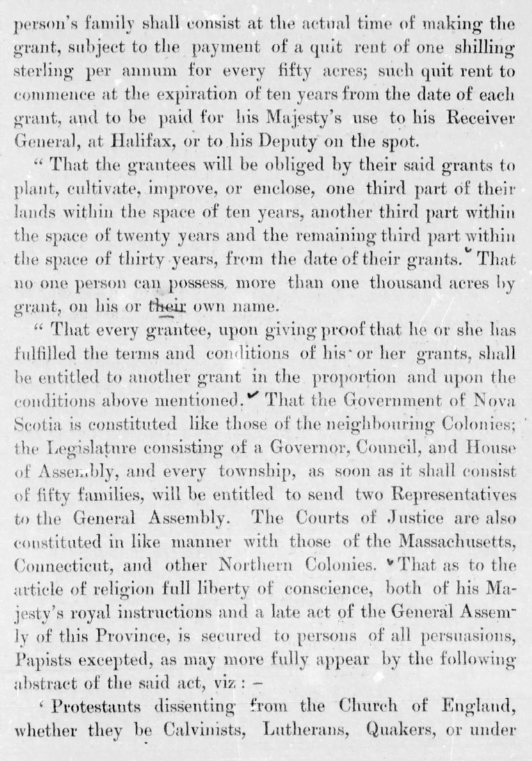

“That the grantees will be obliged by their said grants to plant, cultivate, improve or enclose, one third part of their lands within the space of ten years, another third within the space of twenty years and the remaining third within the space of thirty years, from the date of their grants. That no one person can posses more than one thousand acres by grant, on his or their own name.

“That every grantee, upon giving proof that he or she has fulfilled the terms and conditions of his or her grants, shall be entitled to another grant in the proportion and upon the conditions above mentioned. That the Government of Nova Scotia is constituted like those in neighboring Colonies; the Legislature consisting of a Governor, Council and House of Assembly, and every township, as soon as it shall consist of fifty families, will be entitled to send two Representatives to the General Assembly. The Courts of Justice are also constituted in like manner with those of the Massachusetts, Connecticut and other Northern Colonies. That as to the article of religion full liberty of conscience, both of his Majesty’s royal instructions and a late act of the General Assembly of this Province, is secured to persons of all persuasions, Papists excepted, as may more fully appear by the following abstract of the said act, viz:-

‘Protestants dissenting from the Church of England, whether they be Calvinists, Lutherans, Quakers or under what denomination soever, shall have free liberty of conscience, and may erect and build Meeting Houses for public worship, and may choose and elect Ministers for the carrying on divine service, and administration of the sacrament, according to their several opinions, and all contracts made between their Ministers and congregationalists for the support of their Ministry, are hereby declared valid, and shall have their full force and effect according to the tenor and conditions thereof, and all such Dissenters shall be excused from any rates or taxes to be made or levied for the support of the Established Church of England.’

“That no taxes have hitherto been laid upon his Majesty’s subjects within this province, nor are there any fees of office taken upon issuing the grants of land.

“That I am not authorized to issue any bounty of provisions; and I do hereby declare that I am ready to lay out the lands and make grants immediately under the conditions above described, and to receive and transmit to the Lords Commissioners for Trade and Plantations, in order that the same may be laid before his Majesty for approbation, such further proposals as may be offered by any body of people, for settling an entire township under other conditions that they may conceive more advantageous to the undertakers.

“That forts are established in the neighborhood of the lands proposed to be settled, and garrisoned by his Majesty’s troops, with a view of giving all manner of aid and protection to the settlers, if hereafter there should be need.

Given in the council Chamber at Halifax, this 11th., day of January, 1759, in the 32nd year of His Majesty’s reign.

(Signed) Charles Lawrence.”

“The significance of this document in one respect must have struck the attention of all who are Rhode Islanders in spirit; refer to its lofty sentiments with regard to liberty of conscience.”

Huling, Ray Greene, 1847-1915. The Rhode Island Emigration to Nova Scotia. [Providence, R.I.?: s.n., 1889. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/aeu.ark:/13960/t3nv9vv03

The book delves into the historical and social landscape of Nova Scotia, particularly focusing on religious movements, governance, and societal norms. It begins with a discussion on religious fervor in the late 18th century, influenced by New England revivalism, and the subsequent tensions between Anglicanism and dissenting sects. The text explores the impact of legislation on religious practices and the social dynamics between different religious communities, highlighting the presence of dissenters and the struggles they faced.

Furthermore, it describes the migration patterns from New England to Nova Scotia, emphasizing the collective nature of settlement and the adaptation of New England practices in township organization. The role of government intervention in local governance and its effect on the development of town meetings is examined. Additionally, societal issues such as slavery, education, and moral conduct are addressed, shedding light on the complexities of early Nova Scotian society.

The passage also discusses the repercussions of the American Revolution on religious institutions and the political climate of Nova Scotia, showcasing the diverse responses of ministers and communities to the conflict. It concludes with reflections on the resilience of Nova Scotians amidst uncertainty and the efforts of religious leaders like Henry Alline to provide spiritual guidance during challenging times.

“In the year 1799 the Bishop of Nova Scotia reported to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts that the Province was being troubled by “an enthusiastic and dangerous spirit” among the sect called “Newlights”, whose religion seemed to be a “strange jumble of New England Independency and Behmenism.” Through the teaching of these “ignorant mechanics and common laborers”, the people were being excited to a “pious frenzy,” and a “rage for dipping” prevailed over all the western counties. It was further believed by the Bishop and the Anglican clergy that these sectaries were engaged in a plan for “a total Revolution in Religion and Civil Government.”

“…as Bishop Inglis recognized, the movement was a continuation of the great revival of religion which occurred in New England between 1740 and 1744, it may be properly called “The Great Awakening in Nova Scotia.”

“Although laws — such as 1758’s an Act for the establishment of religious public Worship in this province, and for suppressing popery — were intended only for the proper regulation of the Church of England, and although the Assembly took care to insert a clause in the act providing for the liberty of conscience and freedom of worship for Protestant Dissenters (32 Geo. II, Cap. V, ii), the remaining sections of the act contain very stringent laws against “popish priests,” providing “perpetual imprisonment” for any offenders found within the province after Mar 25, 1759, and a fine of £50 and the pillory for any person harboring, relieving, concealing or entertaining such a priest. These harsh enactments were omitted from the revised laws of 1783, but Test Oaths were required of all Catholics until 1827. The Anglican church was not disestablished until 1851, nevertheless, there was enough of the coercive in the law to arouse the suspicion of the New Englanders… Were not these laws respecting unlicensed teachers and preachers similar to those aimed at the itinerants and exhorters in Connecticut and Massachusetts?”

“…Governor Lawrence was led to issue a second proclamation on January 11, 1759. This document contained the solemn assurances of the government upon the subject of civil and religious liberties within the province, which early won for it the title “The Charter of Nova Scotia.” (T.C. Haliburton, An Historical and Statistical Account of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1829), I, 220. A copy of the original proclamation may be seen in the John Carter Brown Library, Providence, R.I. It also appeared in Boston News-Letter, Feb 15, 1759.)

Regarding religion the proclamation declared:

…full liberty of conscience, both of His Majesty’s royal instructions and a late act of the General Assembly of this Province, is secured to persons of all persuasions, Papists excepted, as more fully appears from the following extract of the said act, viz: “Protestants dissenting from the Church of England, whether they be Calvinists, Lutherans, Quakers, or under what denomination soever, shall have free liberty of conscience, and may erect and build Meeting Houses for public worship, and may choose and elect Ministers for the carrying on of Divine services and administration of the sacrament, according to their several opinions, and all contracts made between Ministers and Congregations for the support of their Ministry are hereby declared valid, and shall have their full force and effect according to the tenor and conditions thereof, and all such Dissenters shall be excused from any rates or taxes to be made or levied for the support of the Established Church of England.”

“With the opening of the Ohio country in 1768, immigration from American colonies practically ceased, and Nova Scotia remained a back-water untouched by the main currents of American migration until the flood-tide of Loyalist refugees burst in upon it at the close of the Revolutionary war. Immigration from the other side of the Atlantic, however, continued.”

“The movement from New England to Nova Scotia was social and not individualistic. Associations of families and not lone pioneers, made the plans, sent their representatives… When they reached their new township they met together, chose their own officers, and laid out their own lands and town-plot. This was all done in accordance with old New England practice. (Cf., R.H. Akagi, The Town Proprietors of the New England Colonies (Philadelphia, 1924), esp. Ch. 1, 3 & 4.)”

“The term “proprietor” is very familiar in New England history. The proprietors were the owners of the land and were responsible collectively for the improvement of the new plantation. “More specifically they were responsible for inducting and enlisting newcomers, for locating home lots and dwelling houses, for building highways and streets, for subdividing the adjacent arable land, and subjecting the meadow and forest, for a time at least to a common management. Records of proprietors meetings at Falmouth, Cornwallis, and Horton show that the Nova Scotia immigrants followed the New England custom.

At the first meeting of the Falmouth proprietors, on June 10, 1760, Shubael Dimock, a former deacon of the Separate Church in Mansfield, Connecticut, was elected Moderator, and, according to custom, a standing committee of three was appointed to manage the prudential affairs of the community. This committee laid out the lands as they had been laid out for over a century in New England; two hundred acres for a Common, sixty acres for a town site and certain tracts for a meeting house, cemetery, school, and for the first resident minister.”

“In one very important respect, however, the Nova Scotian proprietors differed from those in New England. The number of lots or shares in each township was determined by the government and not by the proprietors meeting, and each proprietor received only his exact share; the lands remaining in the township then still remained in the hands of the Crown, and were granted to new proprietors by the Lands Office at Halifax and not by the local proprietors meeting.”

“In 1766 there was a remonstrance from the principal inhabitants of Halifax to the Lords of Trade because “all the scum of the Colonies” was being admitted to the province which they said had been “inundated with persons who are not only useless but burdensome,” and that the passage money of “persons from goals, hospitals and work-houses” was actually being paid by the other colonial governments… There is ample evidence, however, to show that there were among the pioneers self-reliant and socially assured leaders who, given the advantages of a new land, soon forged ahead and achieved prosperity and independence for themselves.”

“The neatly planned towns, with their regularly laid out streets and village greens, did not materialize. Instead, the shortest path across the fields of an absentee owner, or of a deserted homestead, connected the irregularly scattered dwellings of the village.

Because of direct government interference, the associations of proprietors in Nova Scotia never developed into the influential town-meetings which were so familiar in New England. As early as 1761, on the recommendation of Governor Belcher, the Lords of Trade disallowed an “Act enabling proprietors to divide lands held in common,” which had been passed by the first assembly. Belcher’s motive… was to extend the authority of the central government over the townships…

The fate of town-meetings was bound up with the intrigues of the Halifax circle. Instead of permitting the freeholders to elect their own officers, it was arranged that the grand juries of the four principal counties should nominate candidates for the local offices and then the local Justices of the Peace choose from among the nominees the men who should finally be appointed. In this way the offices of the townships were kept in the hands of the friends of the government, or at least that group of enterprising men who held key positions in council. About the only power left to the town meetings was the care of the poor. The change did not pass without protest, but on the whole the towns were too weak to defend “the rights and liberties of Englishmen.”

In 1770 the town meeting of Truro objected to the officers chosen to govern it. Liverpool and other towns also made complaints, but a warning that the Attorney-General had been instructed to prosecute persons who called “Town Meetings for Debating and Resolving on Several Questions Relating to the Laws and Government of this Province” seemed to have a quieting effect. The new settlements were too scattered to unite in any effort to preserve their liberties, and too poor to carry on the struggle. Those who might have been their leaders already held offices under the centralized system and shared in its profits.

It was this lack of leadership, organization, and experience, as well as their remoteness and poverty, which to a great extent determined Nova Scotia’s attitude during the War of Independence. There can be little doubt that Governor Belcher’s policy “prevented the formation of some twenty little republics in western Nova Scotia, and it enabled the central government to establish communications with the townships and to retain a check upon their activities. It also accelerated the moral and social decline which has already been observed.”

“Drunkenness seems to have been the most prevalent evil. Provincial statutes, comparable to the “Blue Laws” of New England, provided severe sentence for all breaches of the criminal code, and for such offenses as profanity, or absence from Church. Church wardens were ordered to walk the streets during the time of divine worship to discover the delinquents. (1 Geo. III, Cap. 1, Acts of the General Assemblies.)

Slavery was practiced by those who could afford it. The Nova Scotia Gazette from time to time carried advertisements such as the following:

Ran Away

On Monday the 10th., of June last, between the hours of 9 and 10 at night, a negro woman named Florimell, she had on when she went away, a red Poppin Gown, a blue baize outside Petticoat, and a pair of Men’s shoes, she commonly wears a handkerchief around her Head, has scars on her face, speaks broken English, and is not very black.. 1 Guinea Rwd. and all charges for their trouble. (Nova Scotia Gazette, July 9, 1776. See Also Ibid., May 28, 1776. The price of slaves varied from £20 to £75 N.S. Money. Cf., T.W. Smith, “The Slave in Canada” N.S.H.S., X, 11 ff.)

In addition to household slaves it was customary for Town meetings to farm-out the local poor. The wealthier rate-payers “bid-off” these unfortunates, who then went to work for them in return for food, lodging and clothes. The town-charges thus became a form of indentured servants, and in addition the good citizen who took them received from the town a sum of money equivalent to his “bid”. (Eaton, Kings County, 162.)”

“Henry Alline, who before his conversion was a leader among the younger set in Falmouth, has left accounts of evenings spent at neighbor’s homes, where the young people amused themselves singing “carnal songs,” telling stories, and causing great mirth by imitating the “extra-ordinaries” of the Newlights, whom some of them remembered before 1760 in Connecticut.”

“In 1765 the Assembly passed An Act Concerning Schools and Schoolmasters, which required all would be teachers to be examined by a minister or two justices of the peace, and to present a certificate of morals and good conduct, signed by at least six inhabitants. He must also take the oath of allegiance. By the same act, boards of school trustees were set up to administer the lands reserved in the original plans of every township for a school. (6 Geo. III, Cap vii, Acts of General Assemblies. The effect of the Act was to place the control of the school lands in the hands of the Anglican clergy, from which they were wrested only after a long and bitter struggle ending in an appeal to the Privy Council in the middle of the nineteenth century. Cf., Eaton, Kings County, 269,270.)”

“…the majority of the population of the province before 1784 were Dissenters. In Halifax, even before the great New England migration of 1760, settlers from the American colonies composed a large and influential part of the community. A protestant Dissenter’s meeting House, known as Mather’s Place in honor of the well-known Boston divines, was erected in 1750 and was supplied by Congregational ministers until the end of the revolution.” (Walter Murray, “History of St. Matthew’s Church,” N.S.H.S., XVI, 137-170.)

“The final blow to congregationalism in Nova Scotia was the American Revolution. (M.W. Armstrong-“Neutrality and Religion in Revolutionary Nova Scotia,” The New England Quarterly, Mar. 1946, 50-62). To the already demoralized and disintegrating churches were now added the calamities of a further loss of ministers, an increased uncertainty because of privateers and possible invasion, and the gnawing uneasiness of a divided loyalty.

By 1775, half of the Congregational pulpits were already vacant. During the war, some of the ministers evinced republican sympathies, but were instantly silenced by the government. The Rev. Benaiah Phelps of Cornwallis was accused of being “an uncompromising Whig” and left the province in 1777. The Rev. Seth Noble of Maugerville, after months of seditious activity, fled to Machias. The Rev. Arzarleh Morse of Granville seems to have been peaceable enough, but at the close of the war gave up his trying charge and returned to New England. John Frost who had been ordained by the church of Jebogue was reported to the Provincial Council in the month of August, 1775, for interfering with a muster of the militia at Argyle and for publicly expressing “his hopes and wishes that the British forces in America might be returned to England confuted and confused. (Minutes of the Council, Aug. 23, 1775. Mr. Frost was deprived of his office as justice of the peace and died shortly after.) The Rev. John Seccomb of Chester was also charged before the Council with “preaching a Sermon tending to promote Sedition and Rebellion,” and with “praying for the Success of the Rebels.” (Ibid., Dec 23, 1776, Jan. 6, 1777) He was placed under a bond of £500 for his future good behavior and henceforth had an uneventful career. Only the Rev. Israel Cheever of Liverpool, “a hard drinker,” and the Rev. Johnathan Scott, the farmer-pastor of Jebogue, avoided the political pitfalls of the times and labored to preserve the New England way in Nova Scotia.

The Presbyterian churches were not so seriously affected by the war… Only the Rev. James Lyon of New Jersey, who had once advised the patient Mr. Bruin Romcas Comingoe “To avoid a party spirit in politics,” showed republican sentiments. Migrating to Machias, Maine, he became the center of plots and schemes to capture Nova Scotian villages and plunder British shipping in the Bay of Fundy. There is some evidence that some of the Ulster settlers in Colchester County shared Parson Lyon’s views. Writing from Halifax to the Secretary of State in 1776, General Massey said, “If you Lordship will pardon me for going out of my walk … I take upon me to tell your Lordship that until Presbytery is drove out of His Majesty’s Dominions, Rebellion will ever continue, nor will that set ever submit to the laws of England.”

“In a time of greatest doubt and discouragement, Alline and his followers in every township pointed out the blessings of peace, and turned men’s thoughts away from the political issues of the day. The uncertain Nova Scotians were made to feel that in contrast with conditions in the other colonies their own lot was good, and that in escaping the horrors of war they had been the particular subjects of divine favor.”

Armstrong, Maurice Whitman, 1905-1967. The Great Awakening In Nova Scotia, 1776-1809. Hartford: American Society of Church History, 1948. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89065270951

This traces the early English colonial ventures in North America, commencing with the establishment of Jamestown in Virginia by the London Virginia Company in 1607. This initial settlement led to further expansions, such as the addition of Bermuda in 1612 and the gradual settlement of the New England coast, including Plymouth and Salem, in the early 17th century. English settlers also began occupying Caribbean islands like St. Christopher’s, Nevis, and Barbados.

The motivations behind these settlements varied, ranging from political and religious strife in England to opportunities for establishing new feudal systems. The English Civil War marked a pause in colonial progress, but the capture of Jamaica in 1655 under Cromwell initiated a new phase of expansion.

In the following decades, territories like Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maine, and New Hampshire were established, while proprietary governments emerged in East and West Jersey, heavily influenced by Quaker ideals. Pennsylvania, founded by Quakers, and Georgia, established as a philanthropic and strategic barrier against Spanish aggression, were significant developments in the early 18th century.

The narrative contrasts English colonial endeavors with Scottish efforts, particularly in Newfoundland, where Scottish adventurers attempted settlements in the early 17th century. Despite facing challenges and disasters, Scottish interest in colonial ventures persisted, although with limited success compared to English counterparts.

The text also highlights the influence of individuals like Sir Ferdinando Gorges and Sir William Alexander in shaping colonial policies and ventures. The Nova Scotia scheme, initiated by Alexander, aimed to create a Scottish colony between New England and Newfoundland, strategically countering French influence in the region.

Despite setbacks in his Nova Scotia voyages, Sir William Alexander remained determined to pursue his colonial enterprise. In 1624, he published “Encouragement to Colonies,” aiming to attract more readers and support. However, while his treatise showcased his scholarly and magnanimous personality, it revealed his misunderstanding of the challenges his scheme faced. A comparison with Captain Mason’s “Brief Discourse” highlights Alexander’s focus on historical narrative rather than practical advantages.

His appeal for colonial support centered on idealistic notions of ambition and virtue, lacking the practical incentives Mason provided. Despite this, Alexander’s prose showed both vivid Elizabethan imagery and a tone reminiscent of Sir Thomas Browne’s solemn grandeur.

To boost colonial interest, King James proposed creating an Order of Baronets, mimicking previous successful efforts in Ulster. By 1624, preparations for a colonizing expedition were underway, financed partly by the baronets’ contributions. Yet, the Scottish gentry showed reluctance, leading to modifications in grant conditions.

In 1629, Sir William’s son led the first Scottish settlement in Nova Scotia, facing minimal French opposition. However, the colony’s history is murky, with sparse records detailing its existence from 1629 to 1632. La Tour’s arrival in 1630 brought reinforcement, but tensions with the French persisted.

Royal support continued, with promises of baronetcies for assistance in the colony. Yet, in 1631, King Charles ordered the abandonment of Port Royal due to French claims. Despite this setback, Sir William’s interest in colonial affairs endured, as evidenced by his involvement in the New England Company and the grant of land in present-day Maine.

Ultimately, Sir William’s colonial ambitions were overshadowed by political turmoil in Scotland, and he did not send out more colonists. Long Island, granted to him, retained its name despite his lack of direct involvement in its settlement.

“The tale of effective English settlement begins in 1607 with the plantation of Jamestown in Virginia by the London Virginia Company. In 1612 the island of Bermuda, discovered three years previously by Sir George Somers, was added by a charter to Virginia, but was later formed into a separate colony. On the reorganization of the Plymouth Virginia Company as the New England Council, followed the gradual settlement of the coast well to the north of Virginia: the decade 1620-1630 saw in its opening year the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth; in its closing year it witnessed the migration of the Massachusetts Bay Company to Salem. In the Caribbean Islands English settlers had, within the same decade, made a joint occupation of St. Christopher’s with the French, and had begun the plantation of Nevis and Barbados. In the following decade, Connecticut and Rhode Island were established; Maine was granted to Sir Ferdinando Gorges; the foundation of New Hampshire was laid by Captain John Mason; and Leonard Calvert, brother of the second Lord Baltimore, conducted a band of emigrants to Maryland.

Some of these settlements owed their origin to the political strife between the early Stuart Kings and those who opposed them either on political or on religious grounds: others, again, were founded by courtiers who saw in the undeveloped lands beyond the Atlantic an opportunity of establishing a new feudalism. By absorbing the energies of Cavalier and Parliamentarian the Civil War brought to a close the first epoch of English colonial progress. The second epoch opened with the capture of Jamaica in 1655 by the expedition under Admiral Penn and General Venables, sent out by Cromwell.

The decade following the Restoration saw the grant of a Charter to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina; the capture of New Amsterdam from the Dutch, followed by the grant of New Jersey to Carteret and Berkeley; the founding of a company for the development of the Bahamas. The next two decades saw the development of East and West Jersey, under Proprietary governments, in which Quaker influence was latterly to become very strong, and this led up naturally to the establishment in 1681 of the Quaker colony of Pennsylvania. The establishment of Georgia in 1732 stands outside the general range of English colonial expansion; it owed its origin partly to the nascent philanthropic tendencies of the eighteenth century, partly to political considerations; designed by Oglethorpe as a colony of refuge for men who had suffered imprisonment for debt, Georgia commended itself both to the American colonists and to the Imperial government as a barrier against Spanish aggression.

To the history of English colonial expansion during the seventeenth century the record of Scottish colonial enterprise in the days before the Union of 1707 offers a striking contrast. Virginia had struggled successfully through its critical early years, and the Pilgrims had crossed the Atlantic before Sir William Alexander received in 1621, from King James, the charter that conveyed to him the grant of Nova Scotia, to be holden of the Crown of Scotland. The expedition that sailed from Kirkcudbright in the summer of 1622 did not even reach the shores of Sir William’s new domain, but was obliged to winter at Newfoundland; the relief expedition dispatched in 1623 did indeed explore a part of the coast of Acadie, but did not effect a settlement.

Thereafter the project languished for some years, but in 1629 a small Scottish colony was established at Port Royal on the Bay of Fundy : its brief and precarious existence was terminated by the Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye in 1632. In 1629, too, a small Scottish colony was planted by Lord Ochiltree on one of the coves of the Cape Breton coast: after an existence of a few months it was broken up by a French raiding force. Half a century after these fruitless efforts to establish Scottish colonies, two attempts were made to form Scottish settlements within the territories occupied by the English colonists: the Quaker Scottish settlement of East Jersey met with considerable success; but after a very brief and very troubled existence the small Presbyterian colony of Stuart’s Town in South Carolina was destroyed by a Spanish force from St. Augustine.

The ever-growing desire of the Scottish merchants to have a colony of their own, to have a market for the goods produced by the factories that began to spring up in Scotland during the closing decades of the seventeenth century, found expression in the eagerness with which Scottish investors entrusted their carefully garnered savings to the Directors of the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies: and never was more tragic contrast than that between the anticipations roused by the Darien Scheme and the tale of disaster that is the record of the Darien expeditions.

Yet though the history of Scottish colonial enterprise reveals but a meagre record of actual achievements, that history is invested with a romantic interest that renders it more akin, in its essential aspects, to the story of French colonial activities in North America than to the somewhat prosaic annals of the English settlements along the Atlantic sea-board. When the Scots came into conflict in North America with their Ancient Ally, the course of events seemed to threaten the very existence of the French power, not only in Acadie, where Port Royal was effectively occupied by the Master of Stirling, but also along the St. Lawrence valley: the security of the ocean gateway to that region was menaced by Ochiltree’s fortalice on Cape Breton Island : in 1629 Champlain surrendered his fort and habitation of Quebec to Captain Kirke, who was operating in connection with the Scots: the thistle had for the moment triumphed over the fleur-de-lys.

It is not wholly chimerical to imagine that if and the St. Lawrence valley had not been surrendered by Charles I. in 1632, the feudal organization designed for Sir William Alexander’s province and the adventurous life that Canadian lake and forest and river opened up to the daring pioneer would have offered to the Scottish military adventurer a congenial sphere of activity and a life quite as attractive as that of a career of arms in Sweden or in Muscovy. And the student of military history who remembers that on the Cape Breton coast, near the spot where Ochiltree’s fortalice was razed to the ground, there was erected a French fort that grew ultimately into the mighty citadel of Louisbourg, will not be unwilling to concede that the Scottish station might well have played an important part in colonial naval and military strategy.”

“Scottish traditions, military, economic and religious—traditions deep-rooted and powerful—united, we have seen, to direct to the continent of Europe, Scotsmen who quitted their native shores to live by the sword, to find a competence in trade, or to seek a temporary shelter from the rigors of political-ecclesiastical persecution. When, indeed, the question of transatlantic enterprise was first brought to the notice of the scots privy council, the emotions which it excited were those of distrust and repugnance.

It must, however, be admitted that the suggested exodus from Scotland against which the lords of the privy council made a diplomatic but firm protest to King James, sixth and first, had been designed by that monarch not wholly in the interests of the prospective emigrants. Towards the close of the year 1617, the star chamber, in pursuance of the royal policy of establishing a lasting peace throughout the debatable land, had evolved a code of stringent regulations for the suppression of disorder there. This code was, of course, applicable only to those districts of the middle shires that belonged to England, but the King had sent a copy of it to the scots privy council with instructions to consider how far the measures designed to impart docility to the English borderers might be made to apply north of the tweed. This question was dealt with by the Scots Privy Council on the 8th January, 1618.

To the line of policy suggested by the thirteenth section of the code, the council took decided exception. This section provided for a survey and information to be taken of the most notorious and leud persons and of their faults within Northumberland, Cumberland, etc., and declared that the royal purpose was to send the most notorious leiveris of them into Virginia or to sum remote parts, to serve in the wearris or in colonies. On the course of action implied in this section the comment of the council was discreet but unequivocal: seeing be the laws of this kingdom and general band every landlord in the middle shires is bounded to be answerable for all these that dwell on his land, the counsel sees no necessity that the course prescribed in the article be followed out here. On this judicious remonstrance the editors of the privy council records make the opposite remark, that Virginia and all the other available colonies of that time being English, the council probably disliked the idea of trusting even Scottish criminals to the tender mercies of English taskmasters.

Three months after the dispatch of this diplomatic non placet, the sage of Whitehall informed the Scottish council that their judgment seemed strange and unadvised and insisted on their acceptance of the principle in dispute. Dutifully they deferred to the royal mandate. Yet the conciliar conscience was not altogether easy concerning the possible fate of kindly scots from the borders: at the beginning of 1619, the council instructed the commissioners of the middle shires to intimate to the transportation sub-committee that in the execution of that piece of service concredit unto them they use the advise and opinion of the lords of his majesty’s privy council.

It is perhaps more than a coincidence that almost at the very time when the king’s desire to employ Virginia as a convenient penitentiary for unruly scots was engaging the attention of the scots privy council, the lord mayor of London and Sir Thomas Smyth, the treasurer of the Virginia company, should be not a little puzzled by a problem that had arisen from King James’ determination to send some of his English subjects to Virginia. It was on 8th January, 1618, that the scots privy council discussed the king’s plan for dealing with turbulent borderers. On 13th January, 1618, King James wrote thus from his “Court at Newmarkitt” to Sir Thomas Smyth:

Trusty and well beloved we greet you well; whereas our court hath of late been troubled with divers idle young people, who although they have been twice punished still continue to follow the same having no employment; wee having no other course to clear our court from them have thought fit to send them unto you desiring you at the next opportunity to send them away to Virginia and to take sure order that they may be set to work there, wherein you shall not only do us good service but also do a deed of charity by employing them who otherwise will never be reclaimed from the idle life of vagabonds…”

This letter Sir Thomas Smyth received on the evening of the 18th of January, some of the prospective deportees had already reached London. The perturbation of the worthy treasurer reveals itself clearly in the letter which he addressed to the lord mayor immediately on the receipt of the royal mandate:

Right Honorable: I have this evening received a lice from his Majesty at Newmarkit requiring me to send to Virginia diverse young people who wanting employment do live idle and follow the court, notwithstanding they have been punished as by his highness lres (which I send your lordship Here with to you to see) more at large appeareth. Now for as much as some of these by his mats royal command are brought from Newmarkit to London already and others more are consigned after, and for that the company of Virginia hath not any ship at present ready to go thither neither any means to employ them or secure place to detain them in until the next opportunity to transport them (which I hope will be very shortly) I have therefore thought fit for the better accomplishing his highness pleasure therein to intreat your lordships favor and assistance that by your Lordship’s favor these persons may be detained in bridewell and there set to work until our next ship shall depart for Virginia, wherein your lordship Shall doe an acceptable service to his majesty and myself be enabled to perform that which is required of me. So I commend you to God and rest.

Your lordships Assured loving friend

Tho. Smith. This Monday evening, 18 January 1618.

Of the subsequent experiences of the young rufflers for whom the treasurer in his perturbation besought the temporary hospitality of the Bridewell the London records give no account.

The deloraines of the debatable land were not the only Scottish subjects of King James for whom the new world seemed to offer itself obligingly as a spacious and convenient penitentiary. In the spring of 1619, while the religious controversy aroused by the issue of the five articles of Perth was still raging bitterly, one of the arguments by means of which Archbishop Spotswood sought to influence the recalcitrant ministers of Midlothian was a threat of banishment to American ominous foreshadowing of the practice that was to become all too common in covenanting days.

At the very time when both King and Archbishop were concerning themselves with the repressive efficacy of exile to Virginia, an obscure group of Scottish adventurers had found in the oldest of England’s transatlantic possessions an attractive, if somewhat exciting sphere of enterprise; and the claims of Newfoundland as a place of settlement suitable for Scottish emigrants were soon to be urged with some degree of ostentation. It is, indeed, but a brief glimpse that we obtain from colonial records of the activities of these Scottish pioneers. In march, 1620, there was received by King James a petition from the treasurer and the company with the Scottish undertakers of the plantations in Newfoundland. After references to the growing prosperity of the country and to the magnitude of the fishing industry, the petitioners complain of the losses caused by the raids of pirates and by the turbulence of the fishermen.

Steps, however, have been taken to combat these evils: and therefor since your majesties subjects of England and Scotland are now joined together in hopes of a happy time to make a more settled plantation in the Newfoundland. Their humble petition is for establishing of good orders and preventing enormities among the fishers and for securing the sd. Plantations and fishers from pirates. That your majesties would be pleased to grant a power to john mason the present governor of our colonies (a man approved by us and fitting for that service) to be lieutenant for your Majesty in the sq. Parts. This petition is endorsed: the Scottish undertakers of the plantation in the New-found-land.”

Brief as is this glimpse of the activities of the early Scottish planters in Newfoundland, and tantalizing as is its lack of detail, the meagre information it yields is of no little interest to the historian of colonial enterprise, for it is the first evidence that has come down to us of Scottish colonizing activity in the new world. Moreover, it affords an eminently reasonable explanation of why captain john mason should seek to stimulate Scottish interest in Newfoundland by the compilation of his brief discourse of the New-found-land … Inciting our nation to go forward in the hopefully plantation begun. Fortunately we can gather from the general course of colonial development in Newfoundland a tolerably complete idea of the plantation in which the scots were undertakers: and it is possible to trace with some fulness both in Scottish and in colonial history the romantic career of captain John Mason.

It lies, of course, primarily within the province of the feudal lawyer to determine how these franchises were to be exercised when there were no vassals to assemble in Court Baron, and This slow progress in the development of Newfoundland was due less to lack of effort on the part of Englishmen interested in colonization than to misdirection of effort. Soon after the annexation there was published A True Report of the Late Discoveries, by Sir George Peckhamthe first of a series of commendatory pamphlets that are useful guides to the early history of Newfoundland. In the retrospective light shed by the later history of the English plantations, it is instructive to consider the nature of the inducements held out, in the year of grace 1583, to prospective pioneers. Much is naturally made of the claims of the fishing industry; but the importance of Newfoundland as a base for a voyage to India by the North-West Passage is also urged; and any feudal instincts that may have survived the ungenial regime of the early Tudors are appealed to by the promise to 100 subscribers of a grant of 16,000 acres of land with authority to hold Court Leet and Court Baron.

The first effective plantation of Newfoundland was carried out early in the seventeenth century by a company imbued with a spirit differing widely from the feudal and romantic tendencies of Peckham. The Company of adventurers and planters of the City of London and Bristol for the colony or plantation in Newfoundland, which received its charter in 1611, had as one of its leading members Sir Francis Bacon, and it was probably through his influence that it obtained, despite the royal impecuniosity, a considerable subsidy from King James. Of the merchants identified with the company, the most prominent was Alderman John Guy of Bristol, who in 1611 conducted the first colonists from the Severn sea-port to Cupid’s Cove, a land-locked anchorage at the head of Harbor Grace. The prosperity that attended this settlement from its earliest days may be ascribed almost with certainty to the guidance it received from the practical counsel of Bacon and the commercial acumen of Alderman Guy. It was with the activities of this settlement at Cupid’s Cove that the Scottish planters had identified themselves.

The only dangers that in any way threatened the success of the colony were the hostility shown towards the planters by the fishermen and the devastation caused by the raids of pirates, and when, in 1615, Guy was succeeded in the governor ship by Captain John Mason, the colonists might with reason feel confident that their destinies had been entrusted to a man well fitted, both by character and by experience, to protect them from their foes.”

“By 1619 Virginia had safely weathered the storms of the early years of its existence. The grant in November, 1620, of the fresh charter to the Plymouth Company, remodeled as The Council established at Ply mouth in the County of Devon, for the planting, ruling, ordering, and governing of New England in America, seemed to promise a more successful issue to the efforts to colonize the more northern part of the territory. The leading part in the reorganization of the Plymouth company was taken by Sir Ferdinando Gorges The Father of English Colonization in North America. With Gorges Sir William was on terms of friendship. The colonizing zeal of Gorges proved contagious.

Alexander’s mind was fired by the possibilities of colonial enterprise. His resolution to engage in such enterprise seems to have been strengthened by arguments adduced by Captain John Mason on his return to England in 1621. Alexander no longer hesitated: he, too, would play his part in colonial enterprise. Having sundry times exactly weighed that which I have already delivered, and being so exceedingly enflamed to doe some good in that kind, he declares in his Encouragement to Colonies, that I would rather bewray the weaknesses of my power than conceal the greatness of my desire, being much encouraged hereunto by Sir Ferdinando Gorge and some others of the undertakers of New England, I shew them that my countrymen would never adventure in such an Enterprise, unless it were as there was a New France, a New Spain, and a New England, that they might likewise have a New Scotland, and for that effect they might have bounds with a correspondence in proportion (as others had) with the Country thereof it should bear the name, which they might hold of their own Crowne, and where they might be governed by their own Lawes.

Sir William’s patriotic desires were respected. On August 5th, 1621, King James intimated to the Scots Privy Council that Sir William Alexander had a purpose to procure a foreign Plantation, having made choice of lands lying between our Colonies of New England and Newfoundland, both the Governors whereof have encouraged him thereunto “and signified the royal desire that the Council would grant unto the said Sir William … a Signatour under our Great Seale of the said lands lying between New England and Newfoundland, as he shall design them particularly unto you. To be holden of us from our Kingdome of Scotland as a part thereof… A charter under the Great Seal was duly granted at Edinburgh on 29th September, 1621.”

For Alexander’s New Scotland the Nova Scotia in America of his Latin charter the New England council had surrendered a territory comprising the modern Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the land lying between New Brunswick and the St. Lawrence. Over the province thus assigned to him Sir William Alexander was invested with wide and autocratic power. Some of the sweeping benefactions of the charter seem to contemplate the transference of Scottish home conditions across the Atlantic with almost too pedantic completeness. Along with many other strange and wonderful things Sir William was to hold and to possess “free towns, free ports, towns, baronial villages, seaports, roadsteads, machines, mills, offices, and jurisdiction;… bogs, plains, and moors; marshes, roads, paths, waters, swamps, rivers, meadows, and pastures; mines, malt-houses and their refuse ; hawking, hunting, fisheries, peat-mosses, turf bogs, coal, coal-pits, coneys, warrens, doves, dove-cotes, workshops, malt-kilns, breweries and broom ; woods, groves, and thickets; wood, timber, quarries of stone and lime, with courts, fines, pleas, heriots, outlaws,… and with fork, foss, sac, theme, infang theiff, outfangtheiff, wrak, wair, veth, vert, venison, pit and gallows…“

The colony which was to enjoy the quaint and multitudinous benefits of Scots feudalism as it then existed and was to exist for another century and a quarter occupied a definite place in the scheme of English colonial expansion, and the effort to found and to hold it was a definite strategic move in the triangular contest of Spain, France and Britain for the dominion of the continent of North America.

The Spanish conquest of Mexico and the establishment of the outpost of St. Augustine on the Florida coast had provided Spain not only with a valuable strategic base in America, but with a claim to the coast lying to the north of Florida. The voyages of Cartier to the St. Lawrence had given France pre-eminence in the North. The seaboard stretching from the St. Lawrence to the peninsula of Florida was claimed by England in virtue of Cabot’s discoveries. The foundation of the Virginia Company in 1606 was a definite effort to make good the English claim.

The Virginia Company had two branches. To the London Company, or southern colony, was given authority to settle the territory between the thirty-fourth and forty-first degrees of north latitude. The founding of the settlement of James town in 1607 by the expedition sent out by the London Company was regarded by the Spanish authorities as a challenge, but the Spanish disfavor did not find expression in open hostilities. A more serious menace than Spanish enmity was found in the life of hardship of the earliest colonists the struggle for subsistence, the hostility of the Indians, the harsh regime of Dale and Argall. But the recognition of the value of the tobacco crop soon brought economic security to the young colony, and the grant in 1619 of a certain measure of self-government to the colony by the establishment of the House of Burgesses, marked the beginning of a happier state of political affairs.

In the Plymouth, or Northern Company, to which was given the right to plant lands between the thirty-eighth and forty fifth degrees of north latitude the most influential man was Sir William Alexander’s friend, Sir Ferdinando Gorges, one of the most interesting characters in early colonial history. Gorges belonged to an old Somerset family. He held the post of governor of the forts and islands of Plymouth, but varied his garrison duty with spells of service abroad. In I591, when about twenty-five years of age, he was knighted by the Earl of Essex for valiant service at the siege of Rouen. When Essex rose in revolt against Elizabeth, Gorges played a vacillating and not too creditable part towards his old commander. The active interest of Gorges in colonial affairs began in 1605 when Captain George Weymouth sailed into Plymouth Sound in the Archangel, a vessel that had been fitted out for trade and discovery by the Earl of Southampton and Lord Arundel of Wardour.

From America Weymouth had brought home with him five Indians. Of these, three were quartered in Gorges’ house. As they became more proficient in the English tongue they had long talks with the Governor, who learned from them much concerning the climate, soil and harbors of their native land. And to the knowledge thus romantically acquired was due the desire on the part of Gorges to take some part in the colonizing of these regions beyond the Atlantic. As a colonizing agent the Plymouth Company, in which Gorges was interested, was less successful than the London Company. The expedition sent out in 1607 by the Plymouth Colony did indeed effect a settlement, the Popham Colony on the coast of Maine, but the rigors of the first winter spent on that bleak sea-board proved too much for the colonists. After the survivors of these settlers returned to England, the activities of the company were connected solely with trading voyages until, in 1620, it was remodeled as the Council for New England.

To the Council was assigned the territory lying between the fortieth and forty-eighth degree of north latitude. Within those limits, too, fishing could be carried on only by permission of the Council for New England, who thus acquired what amounted to a monopoly of the lucrative American fisheries. Both from the rival company of London and from those who, on political grounds, were opposed to monopolies, the Council for New England met with determined opposition. During the meetings held prior to the autumn of 1621 the chief subjects under discussion were the settlement of the company’s territories and the prevention of the infringement of the company’s rights by interlopers trading within its territories or fishing the adjoining seas. It soon became evident that, for the time being, the company was more concerned with exploiting its privileges than with settling its territories, and soon a scheme was evolved for passing on to others the burden of colonization. In September, 1621, Gorges himself laid before the Mayor of Bristol the Articles and Orders Concluded on by the President and Counsel for the affaires of New England for the better Government of the Trade and for the Advancement of the Plantation in those parts. . The salient features of this scheme are contained in Articles I, 2, 3, and 9:

With this grandiose scheme the cautious Merchant Venturers of Bristol would have nothing to do. But the scheme brings out clearly the circumstances in which the Scottish venture had its origin, and reveals the exact significance, from the English standpoint, of the Nova Scotia scheme. By the reorganization of 1620 the northern boundary of the Plymouth Company had been advanced two hundred miles farther north. This northern frontier had now reached the sphere of French influence on the lower St. Lawrence. Already in 1613 an attempt on the part of the French to extend their sphere of influence southward had evoked reprisals on the part of the Virginian colonists, and the French Jesuit settlement at Desert Island on the coast of Maine had been broken up by an expedition under Captain Argall; in the following year Argall sailed north again and sacked the French settlement at Port Royal in the Bay of Fundy. But the French settlers had not been wholly driven from these northern latitudes, and the hope that the occupation of the northern territory by the Scots would prove a barrier against French aggression was responsible for the cordiality with which the Nova Scotia scheme was urged on Alexander by Gorges and the others interested in English colonial projects.”

“Despite the losses caused by the Nova Scotia voyages, however, Sir William was by no means inclined to abandon his enterprise. Ever sanguine and ever ingenious, he resolved to employ the learned pen which had attracted to him the royal favor, in an appeal to a wider circle of readers. In 1624 he published his Encouragement to Colonies, a treatise which is at once a tribute to the scholarly and magnanimous aspects of his personality and a convincing revelation of his inability to grasp the nature of the difficulties against which his scheme had to struggle. It is highly instructive to compare with the Encouragement Captain Mason’s Brief Discourse. Mason’s pamphlet opens with a clear, precise account of the geographical position and the climate conditions of Newfoundland: the first six pages of the Encouragement contain a sketch of the history of colonization from the days of the Patriarchs down to those of the Roman Empire; the next twenty-five pages are devoted to a masterly resume of American history from the time of Columbus down to the settlement of New England.

It will be remembered how definitely Mason set out the particular advantages Newfoundland offered to prospective settlers: Alexander’s appeal, if addressed to higher instincts, was correspondingly vaguer: Where was ever Ambition baited with greater hopes than here, or where ever had Virtue so large a field to reap the fruits of Glory, since any man, who doth go thither of good quality, able at first to transport a hundred persons with him furnished with things necessary, shall have as much Bounds as may serve for a great man, whereupon he may build a Towne of his own, giving it what form or name he will, and being the first Founder of a new Estate, which a pleasing industry may quickly bring to a perfection, may leave a faire inheritance to his posterity, who shall claim unto him as the author of their Nobility there… It is with little surprise that we learn that the only person who seems to have been encouraged by the publication of this treatise was Alexander himself. To the text of the Encouragement there was added a map of New Scotland. With the object of either satisfying an academic craving for patriotic consistency or of dispelling that dread of an unknown land which had proved such a deterrent to the peasants of Galloway, Alexander besprinkled his map with familiar names. And what Scot could persist in regarding as altogether alien, that land which was drained by a Forth and a Clyde, and which was separated from New England by a Twede.

If the Encouragement did little to stimulate colonial enterprise in Scotland, it has an intrinsic interest as a literary production. To a modern reader Alexander’s verse, despite its great reputation in his own day, seems to be strangely lacking in vital interest. It may be that the themes of his Monarchic Tragedies, and of his long poem on Doomesday, appealed to his intellect and not to his heart. But when he wrote of colonial enterprise, he was treating a theme that had fired his imagination, and his prose is vigorous and impressive. Now it is vivid with Elizabethan brightness and colour: his explorers discovered three very pleasant Harbors and went ashore in one of them which after the ship’s name they called St. Luke’s Bay, where they found a great way up a very pleasant river, being three fathoms deep at low water at the entry, and on every side they did see very delicate Meadows having roses red and white growing thereon with a kind of wild Lilly having a very dainty Smell. Again, it strikes a note of solemn grandeur that anticipates the stately cadences of Sir Thomas Browne: I am loth, says Alexander, in referring to Roman military colonization, by disputable opinion to dig up the Tombs of them that, more extenuated than the dust, are buried in oblivion, and will leave these disregarded relicts of greatness to continue as they are, the scorn of pride, witnessing the power of Time.

But if Sir William Alexander’s appeal was made essentially to the higher emotions and interests of his countrymen, his friend the king was ready with a practical scheme designed to impart to either indifferent or reluctant Scots the necessary incentive to take part in colonial enterprise. There is, indeed, in the closing lines of the Encouragement, a hint of the prospect of royal aid : And as no one man could accomplish such a Work by his own private fortune, so it shall please his Majesty… to give his help accustomed for matters of less moment hereunto, making it appear to be a work of his own, that others of his subjects may be induced to concur in a common cause. … I must trust to be supplied by some public helps, such as hath been had in other parts for the like cause. For the public helps the ingenious king, well exercised in all the arts of conjuring money from the coffers of unwilling subjects, had decided to have recourse to a device of proved efficiency the creation of an Order of Baronets. To the Plantation of Ulster welcome assistance had been furnished through the creation of the Order of Knights Baronets: the 205 English landowners who were advanced to the dignity of Baronets had contributed to the royal exchequer the total sum of 225,000. The Ulster creation formed the precedent that guided King James in his efforts to help Sir William Alexander.

In October, 1624, the king intimated to the Scots Privy Council that he proposed to make the colonization of Nova Scotia a work of his own, and to assist the scheme by the creation of an Order of Baronets. Both in their reply to the king and in their proclamation of 30th November, 1624, the Council emphasized the necessity of sending out colonists to Nova Scotia. The terms on which Baronets were to be created were set forth with absolute precision in the proclamation. Only those were to be advanced to the dignity who would undertake To set forth “six sufficient men, artificers or laborers sufficiently armeit, apparrelit, and victuallit for two years . . . under the pane of two thousand merkis usual money of this realm.“

In addition, each Baronet so created was expected to pay Sir William Alexander one thousand merks Scottish money only towards his past charges and endeavors. But the Scottish gentry seemed as reluctant to become Nova Scotia Baronets as the Galloway peasants had been to embark on Sir William’s first expedition. When the first Baronets were created six months after the Proclamation of the Council, the conditions of the grant were modified in certain very essential respects. The terms on which, for example, the dignity was conferred on Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonston, the first of the Nova Scotia Baronets, make it clear that the main condition of the grant was now the payment to Sir William Alexander of three thousand merks, usual money of the Kingdom of Scotland, and that the interests of the colony were safeguarded only by an undertaking on the part of Sir William Alexander to devote two thousand merks of the purchase money towards the setting forth of a colony of men furnished with necessaire provision, to be planted within the said country be the advice of the said Sir Robert Gordon and the remnant Barronets of Scotland, adventurers in the plantation of the same. To render attractive the new dignity various devices were employed.

To enter upon possession of the broad acres of his Nova Scotia territory, the baronet did not require to cross the Atlantic: he could take seisin of it on the Castlehill of Edinburgh. The king urged the Privy Council to use their influence to induce the gentry to come forward. When the precedency accorded to the baronets evoked a complaint from the lesser Scottish barons and the cause of the complainers was espoused by the Earl of Melrose, principal Secretary of Scotland, Melrose was removed from his office and replaced by Sir William Alexander. Certain recalcitrant lairds were commanded by royal letter to offer themselves as candidates for baronetcies. Yet the number of baronets grew but slowly, and the growth of the funds available for fresh colonial efforts was correspondingly slow.”

“By the summer of 1626, Sir William appeared to have hit upon the desired means, for preparations were being made for the dispatch of a colonizing expedition in the following spring. The exact nature of these means is clearly revealed in a letter of Sir Robert Gordon, the premier Nova Scotia baronet, dated from London, the 25th May, 1626. At a meeting held at Wanstead some time previously certain of the baronets had covenanted to provide two thousand merks Scots apiece for buying and rigging forth of a ship for the furtherance of the plantation of New Scotland, and for caring our men thither.”

“Early in 1627 Alexander, probably in order to dispel an uncharitable assumption that the share of the baronets’ money destined for colonial purpose was being diverted to his own use, let it be known publicly that he had fulfilled his share of the compact, ” having…prepared a ship, with ordinance, munition, and all other furniture necessary for her, as likewise another ship of great burden which lyeth at Dumbartoune.” At the same time he made a requisition to the Master of the English Ordnance for sixteen miner, four saker and six falcor, which were to be forwarded to Dumbarton. Strenuous efforts, too, were made by King Charles to further Sir William’s plans. The Scottish Treasurer of Marine was instructed to pay Sir William the £6,000 which represented the losses incurred in the former Nova Scotia expeditions, and which, despite a royal warrant, the English Exchequer either could not or would not pay him: it does not appear, however, that in this matter the Scottish authorities proved in any way more complaisant than the English officials. A week after the issue of these instructions the Earl Marischal was directed to make a selection of persons “fit to be baronets” both among “the ancient gentry,” and also among “these persons who had succeeded to good estates or acquired them by their own industry, and are generously disposed to concur with our said servant (Alexander) in this enterprise.” A month later the Privy Council were urged to use their influence “both in private and public” to stimulate the demand for baronetcies.”

“The validity of the English claim to the region the French did not admit, and despite the destruction of the “habitation” at Port Royal by Argall, the French pioneers did not abandon Acadie. One section of these pioneers, under Claude de St. Etienne, Sieur de la Tour, and his son Charles, did indeed cross the Bay of Fundy and set up a fortified post at the mouth of the Penobscot River. But de Poutrincourt’s son, Biencourt, with the rest of his company, clung to the district round Port Royal, wandering at first amid the Acadian forest, and later succeeding in rendering habitable once more the buildings that had housed the Order of Good Cheer. The death of de Poutrincourt in France in 1615, during civil commotion, left his son in possession of the Acadian seignory.”

“Not only was the district around Port Royal in effective French occupation, but on the Atlantic coast, especially in the district around Canso, there had sprung up a number of sporadic settlements, the homes principally of French and Dutch adventurers. In the presence of these adventurers one writer on Canadian history finds a convincing explanation of why Alexander’s second expedition did not attempt to form a settlement.”

“In the summer of 1629 Sir William Alexander’s eldest son, Sir William the younger, had in vessels belonging to the Anglo-Scotch Company carried a company of colonists to Acadie. On the 1st July, 1629, sixty colonists under Lord Ochiltree were landed on the eastern coast of Cape Breton Island : thereafter Alexander sailed for the Bay of Fundy and landed the remainder of the company of colonists at Port Royal. The first Scottish settlement of Nova Scotia was thus carried out in the summer of 1629.”

“The history of the Scots settlement at Port Royal during the few years of its existence (1629-1632) is exceedingly obscure… Of the incidents connected with the visit to the shores of Nova Scotia we have what is practically an official account in the Egerton Manuscript, entitled “William Alexander’s Information touching his Plantation at Cape Breton and Port Royal.” “…The said Sir William resolving to plant in that place sent out his son Sir William Alexander this spring with a colony to inhabit the same who arriving first at Cap-britton did find three ships there, whereof one being a Barque of 60 Tunnes it was found that the owner belonged to St. Sebastian in Portugal, and that they had traded there contrary to the power granted by his Majesty for which and other reasons according to the process which was formally led, he the said Sir William having chosen the Lord Oghiltrie and Monsieur de la Tour to be his assistants adjudged the barque to be lawful prize and gave a Shallop and other necessaries to trans- port her Company to other ships upon that Coast, according to their own desire, as for the other two which he found to be French ships he did no wise trouble them.

Thereafter having left the Lo. Oghiltree with some 60 or so English who went with him to inhabit there, at Cap-britton, the said Sir William went from thence directly to Port Royall which he found (as it had been a long time before) abandoned and without sign that ever people had been there, where he hath seated himself and his Company according to the warrant granted unto him by his Majesty of purpose to people that part.” No opposition was encountered from the French. Claude de la Tour (son of Monsieur de la Tour, Alexander’s ” assistant “), to whom the seignory of Port Royal had passed on the death of Biencourt, had, after having been driven in 1626 from his fort at the mouth of the Penobscot River, concentrated the remainder of the Port Royal colony at a new station which he had established at the south-eastern extremity of Acadie, in the neighborhood of Cape Sable. The Indians of Acadie entered into friendly relations with the new settlers, and during the summer Port Royal became the depot for a thriving trade in furs. When at the close of the season the company’s vessels sailed for home, Sir William Alexander remained at Port Royal to share with his colonists whatever trials the coming winter might have in store. To the hardships endured in the course of his colonial experiences has been attributed his death in the prime of manhood. With the fleet that sailed from Port Royal in the autumn of 1629 there travelled to Britain an Indian chief, the Sagamore Segipt, his wife, and his sons. The ostensible object of the chief’s journey was to do homage to the King of Britain and invoke his protection against the French. Landing at Plymouth, the Indian party broke their journey to the capital by a short stay in Somersetshire. There they were hospitably entertained. The [indigenous] took all in good part, but for thanks or acknowledgment made no sign or expression at all.

In the summer of 1630 the settlers at Port Royal received a useful reinforcement in the form of a party of colonists under the elder La Tour. Captured by Kirke in 1628, La Tour had been carried to England, and it may well have been his knowledge of Acadie combined with a complaisant disposition that soon advanced him to high favor at Court. He had sailed with Sir William Alexander the Younger to Nova Scotia in 1629. His experiences during this expedition seem to have made him decide to throw in his lot with the Scots, for soon after his return to England there were drawn up, in rough outline, on 16th October, 1629, “Articles d’accord entre le Chevalier Guillaume Alexandre, siegnr de Menstrie Lieut de la Nouvelle Ecosse en Amerique par sa Majeste de la Grande Bretagne, et le Chevalier Claude de St. Etienne, siegnr de la Tour et Claude de St. Etienne son filz et le Chevalier Guillaume Alexandre filz dudt seignr Alexandre cy dessus nome … tant pour leur assistance a la meilleure recognaissance du pays.“

It was not, however, till 30th April, 1630, that the agreement between Alexander and La Tour was definitely signed. “The said Sir Claud of Estienne being present accepting and stipulating by these presents for his said son Charles now absent, so much for the merit of their persons as for their assistance in discovering better the said country.” La Tour obtained two baronies, the barony of St. Etienne and the barony of La Tour, “which may be limited between the said Kt of La Tour and his son, if they find it meet, equally.”

But neither the dignity conferred on him nor the wide stretch of territory that accompanied it appealed particularly to the said son Charles now absent. When the two ships that carried La Tour and his party to Acadie anchored off Fort St. Louis in the neighborhood of Cape Sable, La Tour found his son staunch in allegiance to France. The paternal arguments having failed to influence the Commandant of Fort St. Louis, La Tour made an attempt to storm the Fort, but was repulsed. He then sailed on to Port Royal. In the autumn of 1630 Sir William Alexander sailed for Britain, leaving in command at Port Royal Sir George Home, who in the early summer of that year had ” conveyed himself and wife and children to Nova Scotia animo remanendi.

In the summer of 1631 a fleet dispatched by the Anglo-Scottish Company landed a band of colonists and some head of cattle at Port Royal. Nor were continued evidences of royal support lacking: in the spring of 1631 the Scots Privy Council had received an assurance from the king that he was solicitous for the welfare of the Nova Scotia colony; a little later intimation was received that the furnishing of assistance to the colony would be rewarded by the grant of baronetcies.

Yet on the 10th July, 1631, Sir William Alexander, now Viscount Stirling, received from King Charles instructions to arrange for the abandonment of Port Royal: the fort built by his son was to be demolished, and the colonists and their belongings were to be removed, “leaving the bounds altogether waist and unpeopled as it was at the time when your said son landed first to plant there.

This claim on the part of the French to Port Royal stirred the Scots to remonstrance. “We have understood,” wrote the Privy Council to King Charles on 9th September, 1630, “by your Majesty’s Letter of the title pretended by the French to the Land of New Scotland : which being communicated to the states at their last meeting and they considering the benefit arising to this kingdom by the accession of these lands to this Crown and that your Majesty is bound in honor carefully to provide that none of your Majesties subjects doe suffer in that which for your Majestys service and to their great charge they have warrantably undertaken and successfully followed out, Wee have thereupon presumed by order from the States to make remonstrance thereof to your Majesty, And on their behalf to be humble supplicants, desiring your Majesty that your Majesty would be graciously pleased seriously to take to hart the maintenance of your royal right to these lands, And to protect the undertakers in the peaceable possession of the same, as being a businesses which touch your Majesty honor; the credit of this your native kingdom, and the good of your subjects interested therein, Remitting the particular reasons fit to be used for defense of your Majesty’s right to the relation of Sir William Alexander your Mas Secretary who is entrusted therewith. . .

Despite the failure of his Nova Scotia scheme, Sir William Alexander did not abandon his interest in colonial problems. In January, 1634- 1635, Sir William, now Earl of Stirling, and his son the Master of Stirling, were admitted Councilors and Patentees of the New England Company. On the 22nd April, 1635, the Earl of Stirling received from the “Council of New England in America being assembled in public Court a grant of “All that part of the Maine Land of New England aforesaid, beginning from a certain place called or known by the name of Saint Croix next adjoining to New Scotland in America aforesaid, and from thence extending along the Sea Coast into a certain place called Pemaquid, and so up the River thereof to the furthest head of the same as it tended northward, and extending from thence at the nearest unto the River of Kinebequi, and so upwards along by the shortest course which tended unto the River of Canada, from henceforth to be called and known by the name of the County of Canada. And also all that Island or Islands heretofore commonly called by the several name or names of Matowack or Long Island, and hereafter to be called by the name of the Isle of Stirling...” Sir William sent out no more colonists: he was fully occupied with the stormy politics of Old Scotland. Long Island did not change its name. But the earliest settlers on Long Island bought their lands from James Farrell, who acted as Deputy for the Earl of Stirling.“

Insh, George Pratt, 1883-. Scottish Colonial Schemes, 1620-1686. Glasgow: Maclehose, Jackson & co., 1922. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015012259795, https://www.tradeshouselibrary.org/uploads/4/7/7/2/47723681/scottish_colonial_schemes_1620-1686_~_1922.pdf

- When Halifax was first settled, this side of the harbor was the home and hunting ground of the [Mi’kmaq].

- Soon after the settlement of Halifax, Major Gillman built a saw mill in Dartmouth Cove on the stream flowing from the Dartmouth lakes.

- On September 30th 1749, [Mi’kmaq] attacked and killed four and captured one out of six unarmed men who were cutting wood near Gillman’s mill.

- In August 1750, the Alderney, of 504 tons, arrived at Halifax with 353 immigrants, a town was laid out on the eastern side of the harbor in the autumn, given the name of Dartmouth, and granted as the home of these new settlers.

- A guard house and military fort was established at what is still known as Blockhouse hill [—the hill on King Street, at North].

- In 1751 [Mi’kmaq] made a night attack on Dartmouth, surprising the inhabitants, scalping a number of the settlers and carrying off others as prisoners.

- In July 1751, some German emigrants were employed in picketing the back of the town as a protection against the [Mi’kmaq].

- In 1752, the first ferry was established, John Connor, of Dartmouth, being given the exclusive right for three years of carrying passengers between the two towns.

- Fort Clarence was built in 1754.