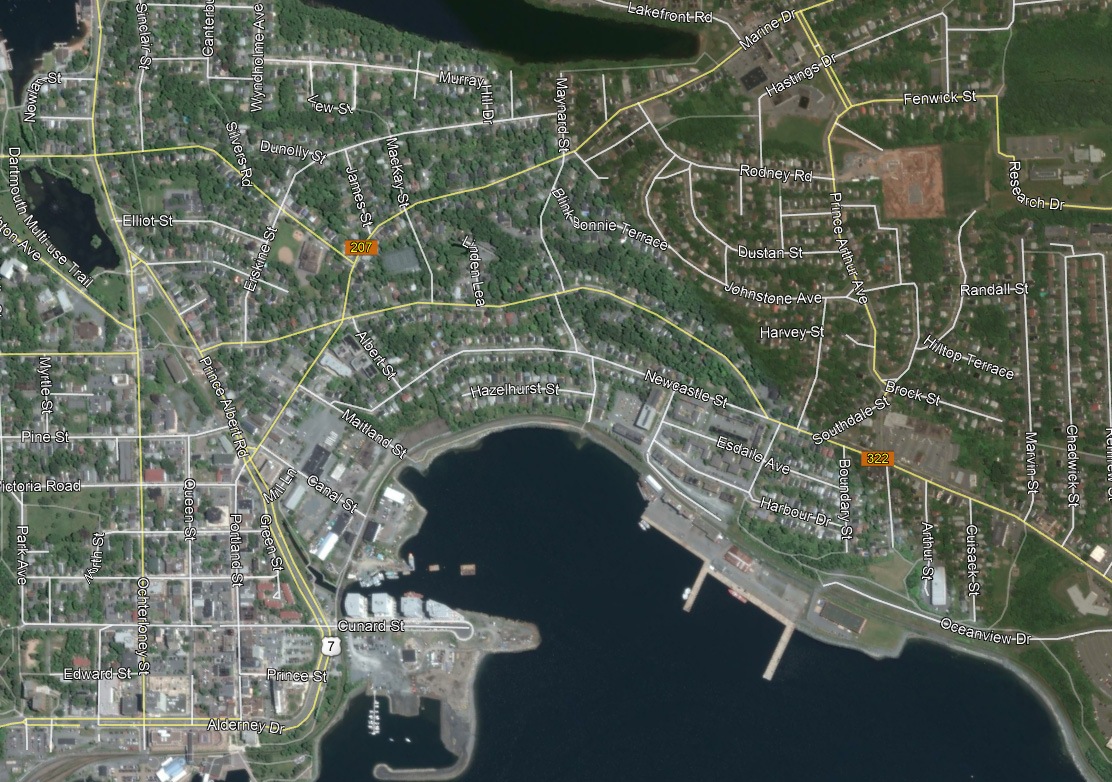

Governor Cornwallis initiated courts of justice based on English common law in 1749, leading to the establishment of County Courts and a General Court. This book asserts that in January 1757 (as do others), Nova Scotia took its first steps in transitioning from being ruled solely by the Governor and Council to establishing a Representative Assembly, comprising twelve members for the province and additional representatives for various townships, including Dartmouth. Members and voters were required to be Protestant, above twenty-one years old, and possess a freehold estate in their district. The first Assembly convened in October 1758 (this time without a representative for Dartmouth), followed by adjustments to representation in subsequent years.

Over time, the judicial system evolved, with the introduction of Circuit Courts and changes in court jurisdictions. The New England town meeting model influenced local governance, coexisting with courts to address various civic matters, including poor relief. Dartmouth held town meetings until its incorporation as a town. The narrative also explores the growth of Baptist communities, the role of the clergy, and the social and political dynamics during the American War. Additionally, it mentions the formation of Light Infantry companies and the challenges faced by Governor Legge in maintaining loyalty during the conflict.

Following this overview, the subsequent text comprises brief biographies of prominent figures and families who are connected to Dartmouth in some capacity.

“Until January, 1757, the Governor and Council ruled alone in Nova Scotia, at that time, after long debate, it was decided that a Representative Assembly should be created, and that there should be elected for the province at large, until counties should be formed, twelve members, besides four for the township of Halifax, two for the township of Lunenburg and one each for the townships of Dartmouth, Lawrencetown (both in Halifax County), Annapolis Royal, and Cumberland. The bounds of these townships were described, and it was resolved that when twenty-five qualified electors should be settled at Piziquid, Minas, Cobequid, or any other district that might in the future be erected into a township, any one of these places should be entitled to send one representative to the Assembly and should likewise have the right to vote in the election of representatives for the province at large.

Members and voters must not be “Popish recusants”, nor be under the age of twenty-one years, and each must have a freehold estate in the district he represented or voted for. The first Assembly met in Halifax on Monday, October 2, 1758, when nineteen members—six “esquires”, and thirteen “gentlemen”, were sworn in. At a meeting of the Council in August, 1759, soon after the dissolution of the second session of the first Assembly, the Council fixed the representation of the township of Halifax at four members, and of Lunenburg, Annapolis, Horton, and Cumberland, at two each. For the newly formed counties of Halifax, Lunenburg, Annapolis, King’s, and Cumberland, there were to be two each.”

County Government, Public Officials:

“When Governor Cornwallis came to Nova Scotia in 1749, one of his earliest acts was the erection and commissioning of courts of justice for the carrying out of the principles of English common law. In pursuance of his orders from the crown he at once erected three courts, a Court of General Sessions, a County Court, having jurisdiction over the whole province, and a General Court or Court of Assize and General Jail Delivery, in which the Governor and Council for the time being, sat at judges. In 1752, the County Court was abolished, and a Court of Common Pleas similar to the Superior Courts of Common Pleas of New England erected in its place. In 1754, Jonathan Belcher, Esq., was appointed the first Chief Justice of the province, and the General Court was supplanted by a Supreme Court, in which the Chief Justice was the sole judge.

In 1829 Judge Haliburton wrote: “There is no separate Court of Common Pleas for the Province, but there are courts in each county, bearing the same appellation and resembling it in many of its powers. These courts when first constituted had power to issue both mesne and final process to any part of the Province, and had a concurrent jurisdiction with the Supreme Court in all civil causes. They were held in the several counties by Magistrates, or such other persons as were best qualified to fill the situation of judges, but there was no salary attached to the office, and fees, similar in their nature, but smaller in amount than those received by the Judges of the Supreme Court, were the only remuneration given them for their trouble. As the King’s bench was rising in reputation, from the ability and learning of its Judges, these courts fell into disuse, and few causes of difficulty or importance were tried in them. It was even found necessary to limit their jurisdiction, and they were restrained from issuing mesne process out of the county in which they sat.

The exigencies of the country requiring them to be put into a more efficient state, a law was passed in 1824 for dividing the Province into three districts or circuits and the Governor was empowered to appoint a professional man to each circuit, as first Justice of the several courts of Common Pleas within the District, and also as President of the courts of sessions. In 1774 an act of the Legislature was passed, first establishing the circuits of the Supreme Court. At Halifax the terms were fourteen days, liberty, however, being allowed for longer terms if the number of cases to be tried demanded an extension of time. No less than eighteen or twenty acts of the legislature relative to the times of holding the courts in the province, were passed between 1760 and 1840. In 1824 an act was passed changing the constitution of the courts of Common Pleas, and dividing the province into three Judicial Districts: the Eastern District, to comprise the county of Sydney, the districts of Pictou and Colchester, and the county of Cumberland; the Middle District, the counties of Hants, King’s, Lunenburg, and Queens; the Western District, the counties of Annapolis and Shelburne. In 1841, by an act of the legislature, the Inferior Courts of Common Pleas were abolished and the administration of law was generally improved.

With the advent of the New England planters to the county, came the introduction of New England’s time honoured institution, the Town Meeting.

[An institution on the radar of those in Dartmouth long before being enacted in law in Dartmouth township, a practice which continued for the first few decades of its existence as an incorporated Town. Martin indicates the last of the “old style” (New England) Town meetings in Dartmouth was held in 1902].

“The New England town meeting was and still is”, says Charles Francis Adams, “the political expressions of the town”, and many writers have spoken of the influence the institution has had in developing and conserving that spirit of independence and sense of liberty which have been characteristic of the New England colonies and colonies sprung from New England. In all the New England settlements in Nova Scotia, the Town Meeting was from the first, in conjunction with the Court of Sessions, the source of local government. The Court of Sessions was composed of the magistrates or justices of the peace, the chairman of which was the Gustos Botulorum, and its secretary, the Clerk of the Peace. By this court, the constables, assessors, surveyors of highways, school commissioners, pound keepers, fence viewers, and trustees of school lands, were appointed. In the Town Meeting the rate-payers met to discuss freely all local affairs, not the least important matter under its jurisdiction being always the relief and support of the poor and the appointment of overseers and a clerk of overseers for carrying out the provisions for the needy the Town Meeting made. For many years it was customary for certain rate-payers to “bid off” one or more poor men, women, or children, for stipulated sums to be paid weekly by the town. In these cases, where it was possible, the rate-payers made the poor whom they bid off, useful in their homes [“parties in need of domestic servants will now have no difficulty in supplying themselves.”]; for such service, and for the sum they received, giving the unfortunates, board, lodging, and clothes. Many persons also, who became town charges were “farmed out” to men who made their living wholly or in part by boarding them. See also “The Great Awakening in Nova Scotia, 1776-1809”, Armstrong, Maurice Whitman] .

Up to 1790, and how much later we do not know, the Town Meetings of Cornwallis were held in the Meeting-House, but after that they were held in some other convenient place. In 1839 an act was passed to enable the inhabitants of Cornwallis to provide a public Town House for the holding of elections in that township. For this building the township was to be assessed in a sum not to exceed two hundred pounds. In 1879 the three townships of the county were united in a central government, and the Town Meeting and Court of Sessions became things of the past. In place of the three townships now arose the Municipality of King’s County, the sole governing body of which is the Municipal Council. Under this new system the county is divided into fourteen wards, twelve of which elect one councillor each, and two, two councillors, for a term of two years. The Council as a whole then elects a Warden, who corresponds to the Custos Rotulorum, of the old Court of Sessions, and whatever other officers it was the duty of the Court of Sessions to elect. Under the Municipality’s control thus came all the interests that formerly pertained to both the Town Meeting and the Court of Sessions. The change of the county to a Municipality was affected at a meeting held at the court house on Tuesday, January 13, 1879, pursuant to a notice by the then Sheriff, John Marshall Caldwell.”

“Before 1888 the only towns in the Province incorporated, besides Halifax, were Dartmouth, Pictou, Windsor, New Glasgow, Sydney, North Sydney, and Kentville.”

“Barristers and Attorneys in King’s County: … James Ratchford De Wolf (long Medical Superintendent of the Insane Hospital at Dartmouth, N. S.)”

“The next rector of Aylesford was the Rev. Richard Avery, son of John and Elizabeth (Simmons) Avery, who was bom at Southampton, England, and educated there, at Warminster, and at Oxford, his brothers, the Rev. John S. Avery, M. A., and the Rev. William Avery, B. A., being chiefly his tutors. Passing the Clerical Board of the S. P. G. in London, Mr. Avery was sent out as a Deacon to Nova Scotia, and by Bishop John Inglis was given the curacy of Lunenburg. In the spring of 1842 he was called as assistant to St. Paul’s Church, Halifax, and Christ Church, Dartmouth”

“In 1827, the Rev. George Struthers, also of the Established Church of Scotland, who afterwards (the Rev. John Martin of Halifax officiating), January 28, 1830, married Mr. Forsyth’s eldest daughter, Mary, and the Rev. Morrison were sent from Scotland by the Lay Association as missionaries to Nova Scotia. At once Mr. Struthers came to Horton, Mr. Morrison going to Dartmouth, which place he afterwards left for Bermuda.”

“The Baptist body in Nova Scotia had its birth in a general religious Revival, and its growth may largely be traced through later similar revivals. Of these revivals King’s County has had always its share, and out of them have come undoubtedly a great deal of deep, continuing religious life.

In 1809 the members of the Cornwallis Baptist Church numbered sixty-five, in 1810 fifty-six, in 1811 sixty-three, in 1812 seventy-three, in 1813 sixty-five, in 1814 sixty-eight, and in 1820 a hundred and twenty-four.

Mr. Manning’s pastorate of the Church lasted until his death, which occurred, as we have said, on the 12th of January, 1851. In 1847, on account of his failing health, the Rev. Abram Spurr Hunt, a young graduate of Acadia College of 1844 (and master of arts of 1851), was chosen to assist him. “When Mr. Manning died Mr. Hunt succeeded to the pastorate, and in this office remained until November, 1867, when he resigned and removed to Dartmouth, the well known suburb of Halifax.”

“On the breaking out of the American War in 1775, Light Infantry companies were ordered by the Governor to be formed in the various townships of King’s and other counties. The number of the King’s County contingent was to be fifty men at Cornwallis, fifty at Horton, and fifty at Windsor, Newport, and Falmouth, together. Fearing sympathy on the part of the Nova Scotians who had come from New England with their rebellious kinsmen in the New England colonies, Governor Legge further ordered that all grown men in the several townships should take an oath of allegiance to the British Crown. … Among the men sent from England to govern the province of Nova Scotia during nearly a century and a quarter, not one ever showed such ill-temper as Governor Legge, the incumbent of the governorship at the outbreak of the war. His charges of disloyalty towards England included, not only the inhabitants of the province who had recently come from New England, but the staunchest members of the Council at Halifax as well. As early as January, 1776, he writes disparaging letters concerning the New England settlers to the British Secretary of State. A law has been passed, he says, to raise fresh militia troops, and he has been endeavouring to arm the people, but he has just been informed from Annapolis and King’s counties that the people in general refuse to be enrolled. Though Governor Campbell ‘s report to Lord Hillsborough in 1770 had stated that he did not discover in the people of Nova Scotia any of that “licentious principle” with which the neighbouring colonies were infected, it is a well known fact that in Cumberland, in 1776, the greatest disaffection towards England did prevail. That it would have been perfectly natural if the people of the midland counties of Nova Scotia had sympathized with New England in her protest against the abuse of power on the part of the British Government from which she had long suffered must be freely admitted, that among the inhabitants of Annapolis, King’s, and Hants such sympathy was outwardly shown, remains yet to be proved.

It is a well known fact that the King’s Orange Rangers, a Loyalist corps raised in Orange County, New York, through the efforts of Lieut.-Col. John Bayard in 1776 and ’77, in October, 1778, were sent to reinforce the King’s troops in Nova Scotia, and that until the disbandment of the corps in 1783 they were employed chiefly in garrison duty in Halifax. The statement of the writer of the manuscript in question is that in King’s County symptoms of rebellion strongly showed themselves, one of these being that certain King’s County people were even preparing to raise a liberty pole. This seditious spirit in King’s being reported to the government at Halifax by Major Samuel Starr, a detachment of the Orange Rangers stationed at Eastern Battery, Halifax, was ordered to Cornwallis, under command of Major Samuel Vetch Bayard.”

Biographies:

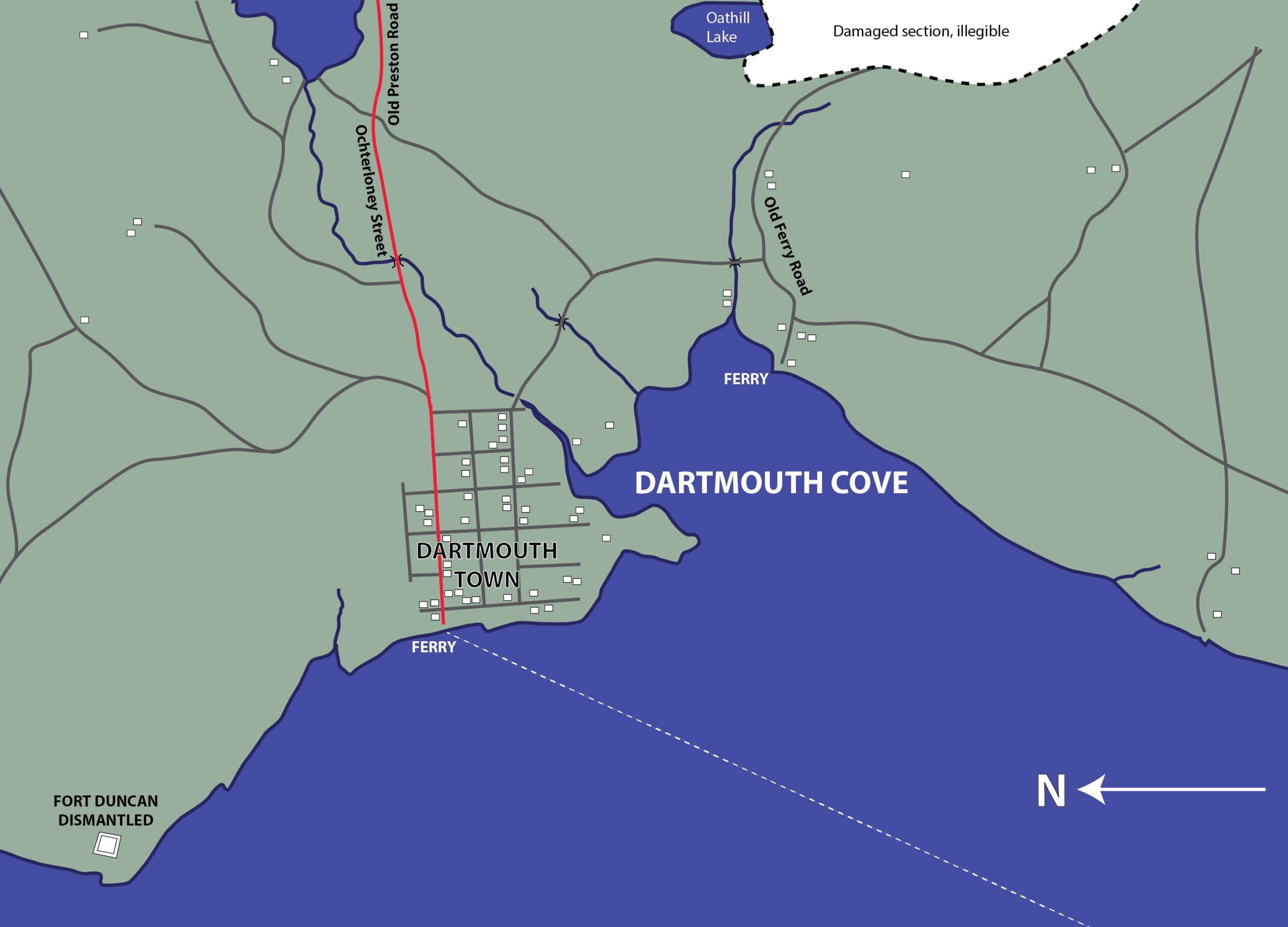

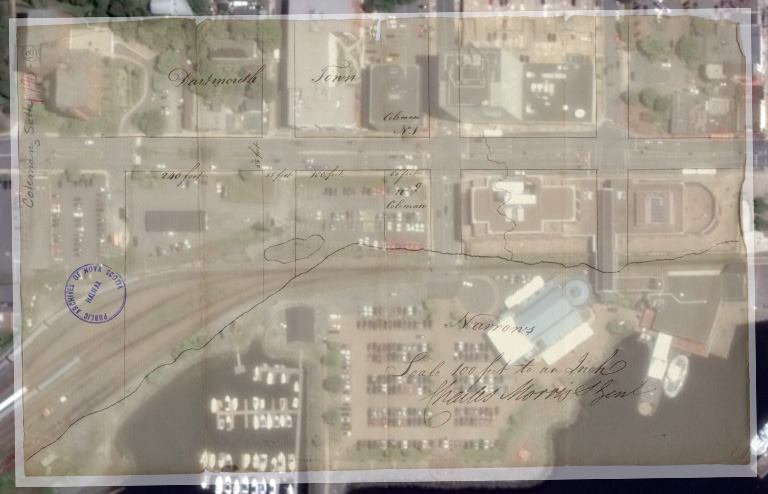

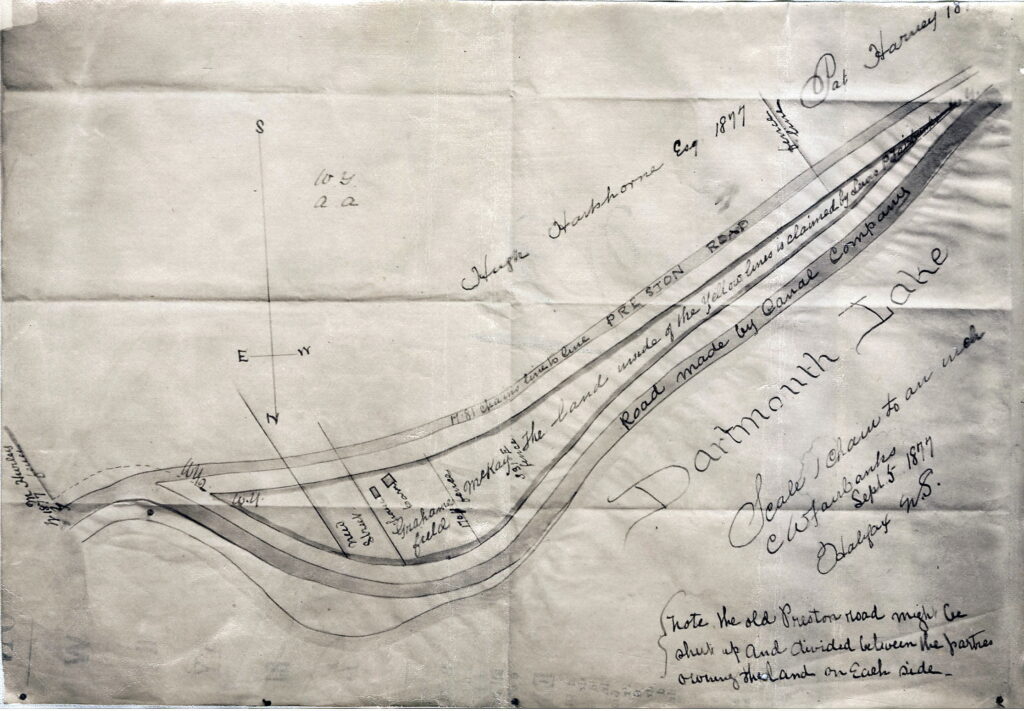

“JAMES Fillis AVERY, M. D. Dr. James Fillis Avery, son of Cap.t. Samuel and Mary (Fillis) Avery, was born in Horton, May 22, 1794, and for three years studied medicine with Dr. Almon in Halifax. He then went to Edinburgh, where he graduated in 1821. After graduation he spent six months in the Hospital of the Royal Guard at Paris, under the superintendence of the noted Baron Larrey, the first Napoleon’s principal medical adviser. Dr. Avery practised medicine in Halifax and also founded there, in George Street, the noted drug firm, which for many years he personally conducted. From this firm, in time, sprang the firms of Messrs. Brown Brothers, and Brown and “Webb. In later life he retired from business, and for some time travelled in Europe. He was an early governor of Dalhousie College, was an elder in St. Matthew’s Presbyterian Church, on Pleasant Street, and was interested in many philanthropic institutions. Among the business enterprises that he took substantial interest in was the Shubenacadie Canal, from Dartmouth to the Bay of Fundy. The first (and probably only) vessel that ever went through that canal, it is said, was called for him. The Avery. For many years, until his death. Dr. Avery’s residence was on South Street, adjoining that of Mr. George Herbert Starr, who had married his niece, Rebecca (Allison) Sawers. Dr. Avery died unmarried, universally respected, Nov. 28, 1887, and was buried near his parents at Grand Pre.

ALFRED CHIPMAN COGSWELL, D. D. S. Alfred Chipman Cogswell, son of Winckworth Allen and Caroline Eliza (Barnaby) Cogswell, was born in Upper Dyke village, Cornwallis, July 17, 1834. He married, Oct. 8, 1858, Sarah A., dau. of Col. Oliver and Sarah A. Parker, born in Bangor, Me., Oct. 10,1830, and had two sons. His residence for many years was in Halifax and in Dartmouth. Dr. Cogswell studied for two years at Acadia College, and then on account of ill health abandoned his college course. His studies in dentistry were later pursued in Portland, Me., and his first practice was in Wakefield, Mass. In 1859 he removed to Halifax, N. S., where he formed a partnership with Dr. Lawrence B. Van Buskirk. Some years later he graduated as D. D. S. at the College of Dentistry in Philadelphia. For many years Dr. Cogswell was a successful and skillful practitioner in Halifax, where he was also an elder in St. Matthew’s Presbyterian Church. The younger of his sons, Arthur W., in 1884 received the degree of M. D., and was appointed Surgeon of the Halifax Provincial and City Hospital.

HON. THOMAS ANDREW STRANGE DeWOLF, M. E. G. Hon. Thomas Andrew Strange DeWolf, M. P. P., M. E. C, fourth son of Judge Elisha and Margaret (Ratchford) DeWolf, born April 19, 1795, married December 30, 1817, or March 26, 1818, his first cousin, Nancy, daughter of Col. James and Mary (Crane) Ratchford, born June 1, 1798. Mr. DeWolf represented the County of Kings from 1837 until 1848. He was made a member of H. M.(first) Executive Council, February 10, 1838, and was subsequently Collector of Customs. When a qualification bill authorizing the election of non-resident members was introduced in the legislature as a government measure, he resigned from the Executive Council. He died at “Wolfville, September 21, 1878 ; his widow died at Dartmouth, March 10, 1883. Hon. T. A. S. DeWolf had fourteen children, the most important of whom was James Ratchford DeWolf, M. D., L. R. C. S. E. and L. M., of the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh.

THE REV. ABEAM SPURR HUNT, M. A. Eev. Abram Spurr Hunt, though not a native of King’s County, was for many years, as Rev. Edward Manning’s immediate successor, pastor of the Cornwallis First Baptist Church. He was born at Clements, Annapolis county, April 7, 1814, grad. at Acadia in 1844 (its second class), and on the 10th of Nov. of that year, was ordained over the newly formed Baptist Church at Dartmouth, N. S. In 1844 also, he married Catharine Johnstone, eldest surviving daughter of Lewis Johnston, M. D., and niece of Hon. Judge James William Johnstone, and in 1846, removed to Wolfville, where for a winter he studied theology under the Rev. Dr. Crawley. In 1847 he became assistant pastor to Rev. Edward Manning at Cornwallis, and in 1851, at Mr. Manning’s death, succeeded to the pastorate. Until 1867 he continued pastor of the Cornwallis Church, his ministry being in every sense a successful one. His field of labour, however, was so wide and his duties so arduous that at last he was obliged to seek an easier parish. When he determined to remove from Cornwallis, the Dartmouth Church recalled him, and to that Church he continued to minister till his death, which occurred, October 23, 1877. In 1870 he was also made Superintendent of Education for the Province, and the duties of this office he also discharged until his death. Mr. Hunt’s children were: Eliza Theresa, married as his 2nd wife, to the Hon. Judge Alfred William Savary, of Annapolis, so well known as a jurist and historian (see among other writings, the Calnek-Savary “History of Annapolis,” and the “Savary Family”); Lewis Gibson, M. D., D. C. L., of London, England ; James Johnstone, D. C. L., Barrister of Halifax; Aubrey Spurr; Ella Maud, m. to the Rev. Arthur Crawley Chute, D. D., Professor in Acadia University ; Rev. Ralph M., a clergyman, who died young, deeply lamented. Mrs. Abram Spurr Hunt, a woman of high breeding and exalted Christian character, survived her husband between seventeen and eighteen years. She died in Dartmouth, Halifax, May 29, 1895.

MAJOR GEORGE ELEANA MORTON Major George Eleana Morton was one of King’s County’s most excellent and enterprising sons. He was a son of Hon. John and Anne (Cogswell) Morton, was born at Upper Dyke village, Cornwallis, March 25, 1811, and was one of the pupils of the Rev. William Forsyth. Going to Halifax at about eighteen years of age he entered a drug store on Granville Street, which business he afterward purchased. In 1852 he erected the stone building at the corner of Granville and George Streets, long known as “Morton’s Comer,” where for many years he conducted a wholesale and retail drug business, at that time the largest in the province. He was the first business man in Halifax to send out a commercial traveller. About 1870 he closed his drug business and opened a book and periodical store, and a lending library of current literature. He retired from business in 1888, and died as the result of an accident, Mar. 12, 1892, and was buried in Dartmouth. Mr. Morton was a man of great intelligence, and of distinctly literary tastes, and his contributions to the press, both in prose and verse, were numerous. In 1852 he published, in conjunction with Miss Mary J. Katzmann, The Provincial, a monthly magazine. Later he published a satirical magazine called Banter. In 1875 he wrote and published the first “Guide to Halifax,” and in 1883, a “Guide to Cape Breton.” His newspaper articles appeared chiefly in the Guardian, the British Colonist, and other newspapers. He was unusually well read in English literature, and his writings contain many quotations from classical authors. He was an accomplished letter writer, and for many years kept up an interesting correspondence with friends abroad, especially with his cousin. Dr. Charles Cogswell. He was one of the original members of the N. S. Historical Society, and was always actively interested in the work of that Society. In religion he was a Presbyterian, his membership being in St. Matthew’s Church. In politics a Conservative, he was for many years a personal friend of Messrs. Johnstone, Tupper, Parker, Holmes, Marshall, and other Conservative leaders. He was an ardent supporter of confederation, and had great faith in the future of the Dominion. Nov. 23, 1859, he was appointed 1st Lieut, in the 2nd Queen’s Halifax Regt. ; Sept. 23, 1862, he was appointed Captain. On the reorganization of the militia by the Dominion Government he was retired with the rank of Major. He was one of the promoters of the N. S. Telegraph Company, was original shareholder of the N. S. Sugar Refinery, and shortly after the discovery of gold in 1860, became interested in gold-mining. He held mining claims at Waverly, Montagu, Elmsdale, and Lawrencetown. George Elkana Morton married in Halifax, in March, 1849, Martha Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Christian Conrad Casper and Martha (Prescott) Katzmann, bom Apr. 2, 1823, died Apr. 6, 1899. He had children: Annie, born Dec. 13, 1850, died Mar. 29, 1855; Charles Cogswell, born Aug. 14, 1852, married Apr. 27, 1905, Winifred, daughter of Leonard and Lucy Leadley, of Dartmouth, N.S., and now resides in Kentville. For the Katzmann Family, see the Prescott Family Sketch.”

“Of the Bishop families of Horton many members have occupied positions of trust and many have attained prominence in the communities where they lived. Such have been … Watson Bishop, of Dartmouth, N. S., Superintendent of Water Works for that town”

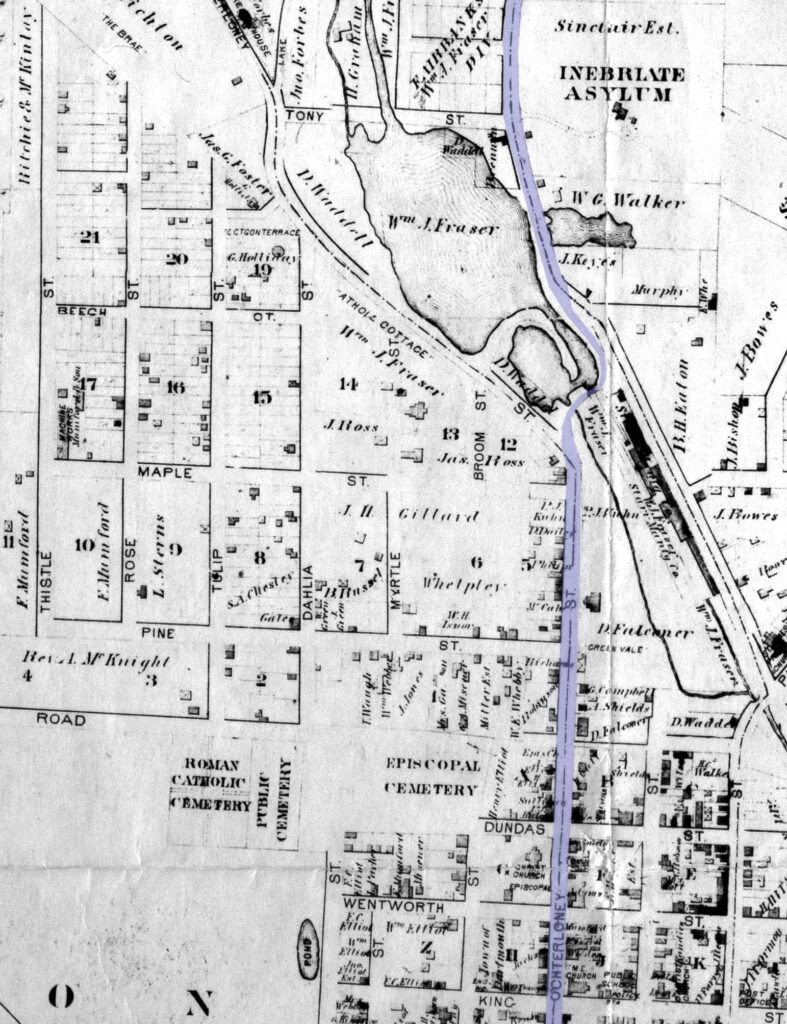

“THE KEMPTON FAMILY The Rev. Samuel Bradford Kempton, D. D., now of Dartmouth, N. S., but for many years the honoured third pastor of the Cornwallis First Baptist Church, in succession to the Rev. Abram Spurr Hunt, is the son of Stephen and Olivia Harlowe (Locke) Kempton, and was b. at Milton, Queen’s county, Nov. 2, 1834. He received his early education at Milton Academy, and in 1857 entered Horton Academy. In 1862 he graduated, B. A., at Acadia University. He then spent a year at Acadia under the instruction of Rev. John Mockett Cramp, D. D., in post-graduate work. In 1833 he was ordained pastor of Third Horton Baptist Church, and in 1867 became pastor of the First Cornwallis Baptist Church. In that position he remained until 1893, when he removed to Dartmouth, as pastor of the Dartmouth Baptist Church. Dr. Kempton received his M. A., from Acadia University in 1872, and the honorary degree of D. D. in 1894. Prom 1878 to 1907 he was one of the governors of Acadia, and in 1882 was appointed a member of the Senate of the University. His ministry at Cornwallis was laborious and faithful, he had six preaching stations and was obliged to travel many miles every week. He married in Horton, Oct. 1, 1867, Eliza Allison, dau. of Abraham and Nancy Rebecca (Allison) Seaman, and had two children : Rev. Austin Tremaise, b. Feb. 6, 1870, m. June 7,1893, Charlotte H. Freeman; William Bradford, b. May 29, 1885, d. July 17, 1893. Of these sons, Rev. Austin Tremaise Kempton graduated at Acadia University in 1891, and received his M. A. in course in 1894. He was ordained to the Baptist ministry at Milton, Queen’s county, N. S., in 1891, later studied at Newton Theological Seminary, and has since held pastorates in Sharon, Boston, Pitchburg and Lunenburg, Mass. He has also been a successful lecturer, his lectures on the “Acadian Country” having done much to make the charms of King’s County known throughout New England.

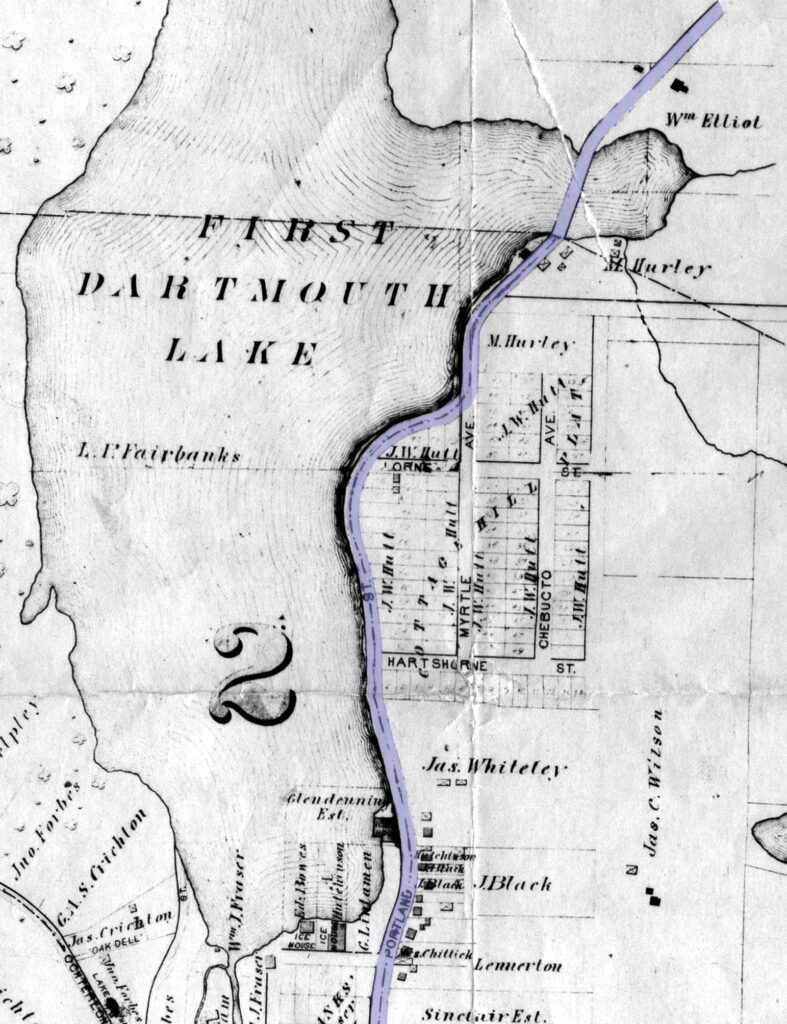

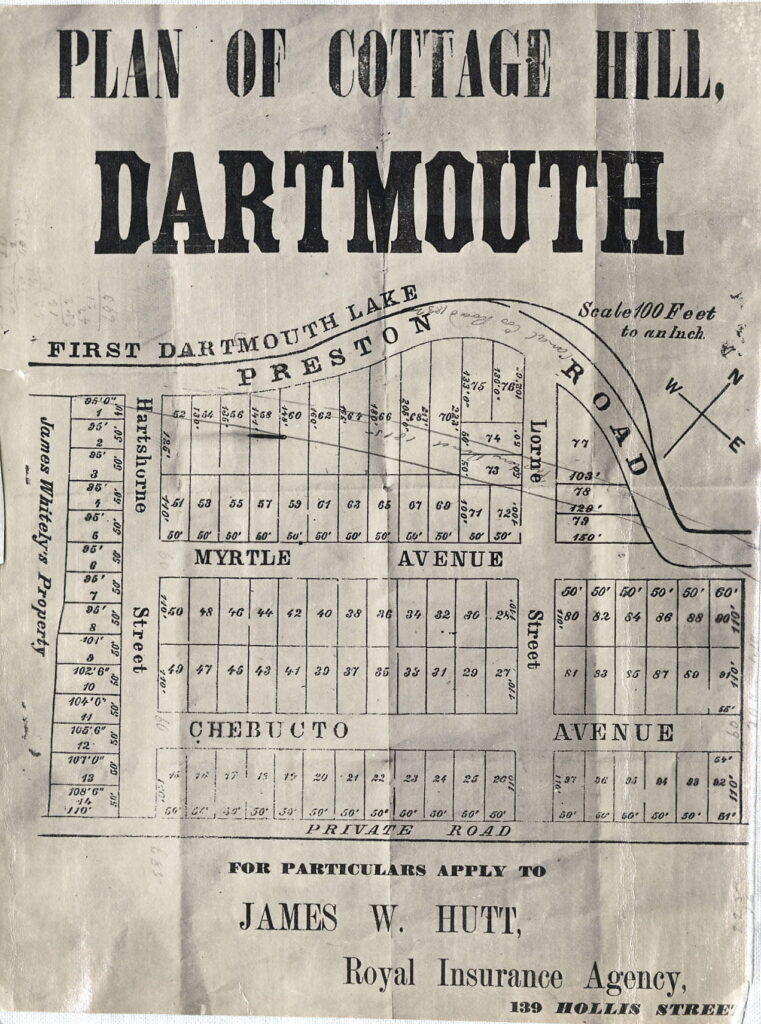

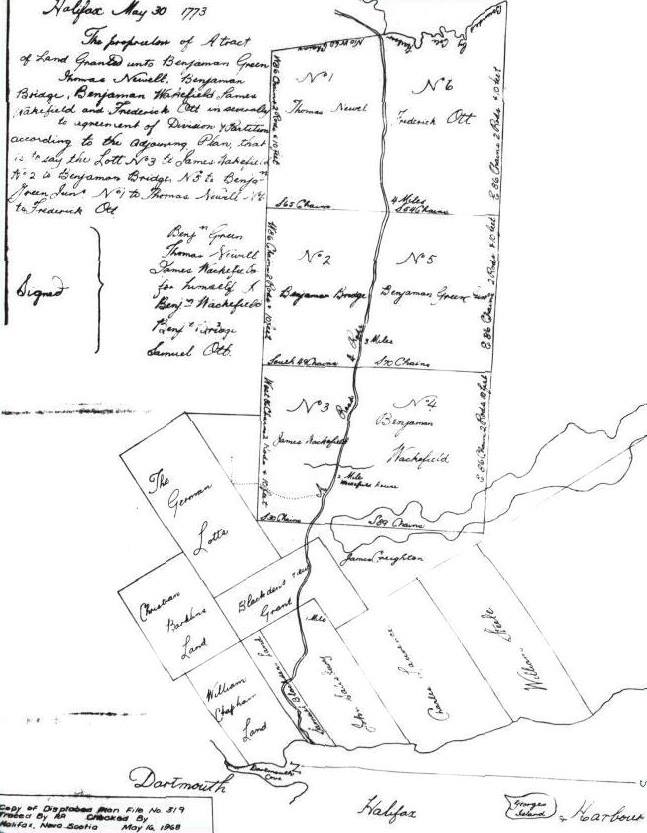

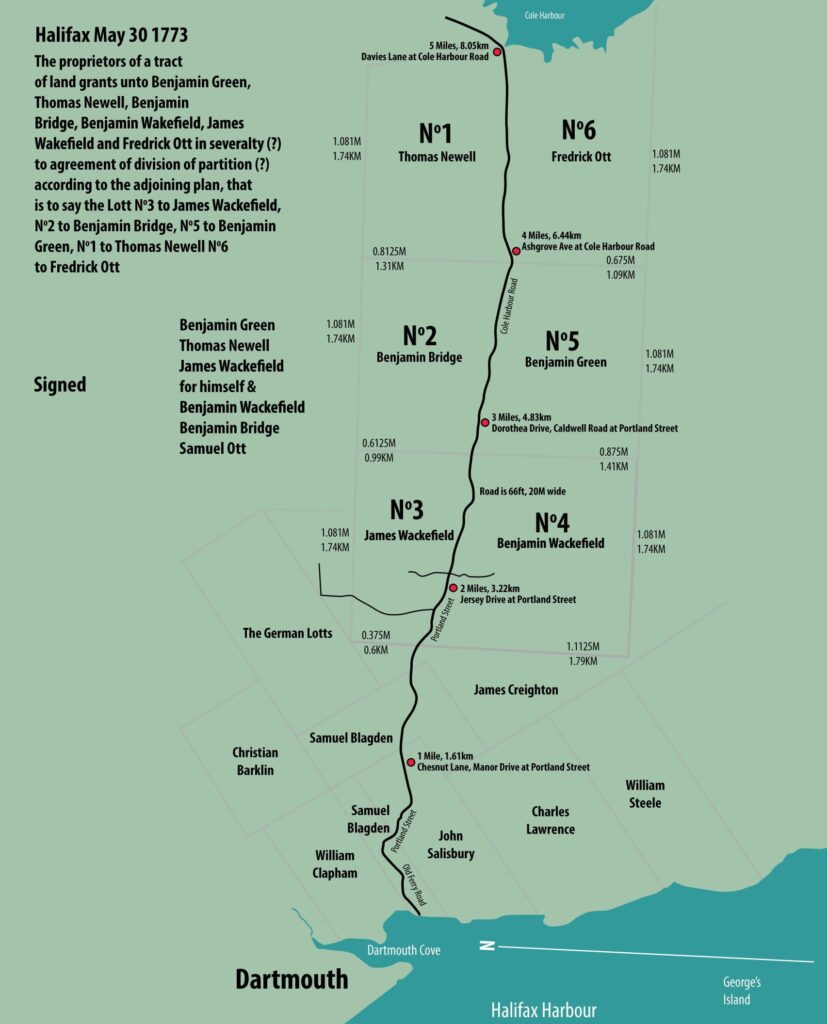

Of one, at least, of the Orpin grantees, and the family from which he sprang, a writer in the Halifax Herald of January 25, 1899, gave the following interesting account: Among the enterprising pioneers who first came to this part of the country to make of the wilderness a fruitful field, was Joseph Moore Orpin and his wife, Anna Johnson Orpin. Mr. Orpin ‘s father, Edward Orpin, was one of the founders of the city of Halifax. He first took up land on the Dartmouth side of the harbor, and employed men to subdue and clear it of a forest of trees and a heavy crop of stone.

One day while he was on his way with a lad, sixteen years old, named Etherton, carrying dinner to the men working on his land, he was surprised and captured by the [Mi’kmaq]. They compelled silence and began their march with their captives in the direction of Shubenacadie. They had not gone far when one of the [Mi’kmaq] gave the boy a heavy blow, felling him to the ground. Instantly his crown was scalped and he was left for dead. After travelling some distance, Mr. Orpin found that one of his shoes was unbuckled. He stopped and pointed it out to the [Mi’kmaq] walking behind him. As he stooped down to buckle it the [Mi’kmaq] stepped ahead of him. Orpin saw his chance, caught up a hemlock knot, and as quick as lightning gave the [indigenous man] a blow which brought him to the ground. He had confidence in his own fleetness of foot. Instantly he was flying for liberty.

As soon as the [Mi’kmaq] in advance discovered the trick, and recovered from their surprise, they gave him chase. But Orpin was too fleet for them. He escaped and reached home in safety. Strange to relate the boy returned to the city soaked from head to foot in his own blood. The doctors of the city did what they could to heal his scalp wound. They succeeded only in part. Directed by them a silversmith made a silver plate, which the young fellow wore over his unhealed wound. After a time he returned to England.

In the same year Mr. Orpin had still another adventure with the [indigenous] neighbors of the young colony. On this occasion, too, he was on his way to the place where his men were at work, carrying them their dinners. Again he was seized by the skulking [Mi’kmaq] , and hurried away toward Shubenacadie. After reaching one of the lakes, the [Mi’kmaq] stopped to take a meal. For a special treat, Mr. Orpin was carrying a bottle of rum to his men with their dinners. At the lake the [Mi’kmaq] drank the whole of it, and it made them helplessly drunk. This was good fortune for the captive. He reached Halifax again with the scalp safe on his head. This last experience made him more cautious for a long time. The stony ground in Dartmouth, and his trouble with the [Mi’kmaq], induced him to give up his Dartmouth lot and commence anew on the Halifax side of the harbor. Some years later, he went to the North West Arm. He never returned. Diligent and thorough search was made for him; but he could not be found. The belief at the time was the [Mi’kmaq] caught him again and took secret revenge on him in torturing him to death at their leisure.”

“…the Katzmann family of Halifax county demands notice. Lieut. Christian Conrad Casper Katzmann, b. in Eimbeck, Hanover, Prussia, Aug. 18, 1780, came to Annapolis Royal, N. S., as ensign (he is also called adjutant, 3rd Battalion) of H. M. 60th Regt. He m. (1) in Annapolis Royal (by Rev. John Millidge), June 11, 1818, Eliza Georgina Fraser (who had a sister, Mrs. Robinson, and a brother, James Fraser, Jr., Postmaster at Augusta, Georgia), who d. shortly before April 5, 1819. He m. (2), April 6, 1822, by Bishop Inglis, Martha, dau. of John and Catharine (Cleverley) Prescott, of Maroon Hall, Preston, Halifax county, and retiring from the army, bought Maroon Hall. His children by his 2nd marriage were Martha Elizabeth, b. April 2,1823, m. to George Eleana Morton ; Mary Jane (the authoress), b. Jan. 15, 1828, m. to William Lawson, of Halifax; Anna Prescott, b. Sept. 25, 1832, d. unm.. May 31, 1876. Lieut. Katzmann and his family are buried in Dartmouth, N.S. Mr. and Mrs. John Prescott are probably buried at Preston.”

“THE PYKE FAMILY The Pyke family in King’s County is descended from John Pyke, who came to Halifax with Governor Cornwallis in 1749, it is said as his private secretary, and was killed by Indians in Dartmouth, in August of the next year. His wife was Anne Scroope, b. in 1716, her grandfather or his brother, it is believed, being a baronet in Lincolnshire. Precisely how long before he came to Halifax John Pyke married, it is impossible to say, but his son (and only child, so far as is known), John George, was born in England in 1743. After her first husband’s death, Anne (Scroope) Pyke was married to Richard Wenman, another of the company that came with the Cornwallis fleet, and to her second husband she bore three daughters: Susanna, married to Hon. Benjamin Green, Treasurer of the Province; a daughter m. to Captain Howe, of the Army; another daughter m. to Captain Pringle of the army. Mrs. Anne Wenman died May 21, 1792 ; her husband, Richard Wenman, was buried Sept. 30, 1781.”

Eaton, Arthur Wentworth Hamilton. The history of Kings County, Nova Scotia, heart of the Acadian land. Salem, Mass., The Salem press company, 1910. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/10025852/