A few interesting notes about initial attempts to settle Halifax are included here, as well as some details about the settlement of Dartmouth. The entirety of Chapter five is included also, a thorough overview of Nova Scotia’s legal and constitutional situation and its place outside the realm, some interesting observations on the constitutional nature within England itself, as well as the various institutions that were a part of life previous to the “paper revolution” that introduced “Responsible government” (previous to the overthrow of Nova Scotia’s constitution in an 1867 coup known as “confederation”).

“The beauty and the safety of this (Halifax) harbor attracted the notice of speculators at a very early period, and many applications were at different times made, for a grant of land in its vicinity. The famous projector, Captain Coram, was engaged in 1718, in a scheme for settling here; and a petition was presented by Sir Alexander Cairn, James Douglas, and Joshua Gee, in behalf of themselves and others, praying for a grant upon the sea coast, five leagues S.W. and five leagues N.W. of Chebucto, upon condition of building a town, improving the country around it, be raising hemp, making pitch, tar and turpentine, and of settling two hundred families upon it within three years. This petition received a favorable report from the Lords of Trade; but as it was opposed by the Massachusetts’s agents, on account of a clause restricting the fishery, it was rejected by the Council.”

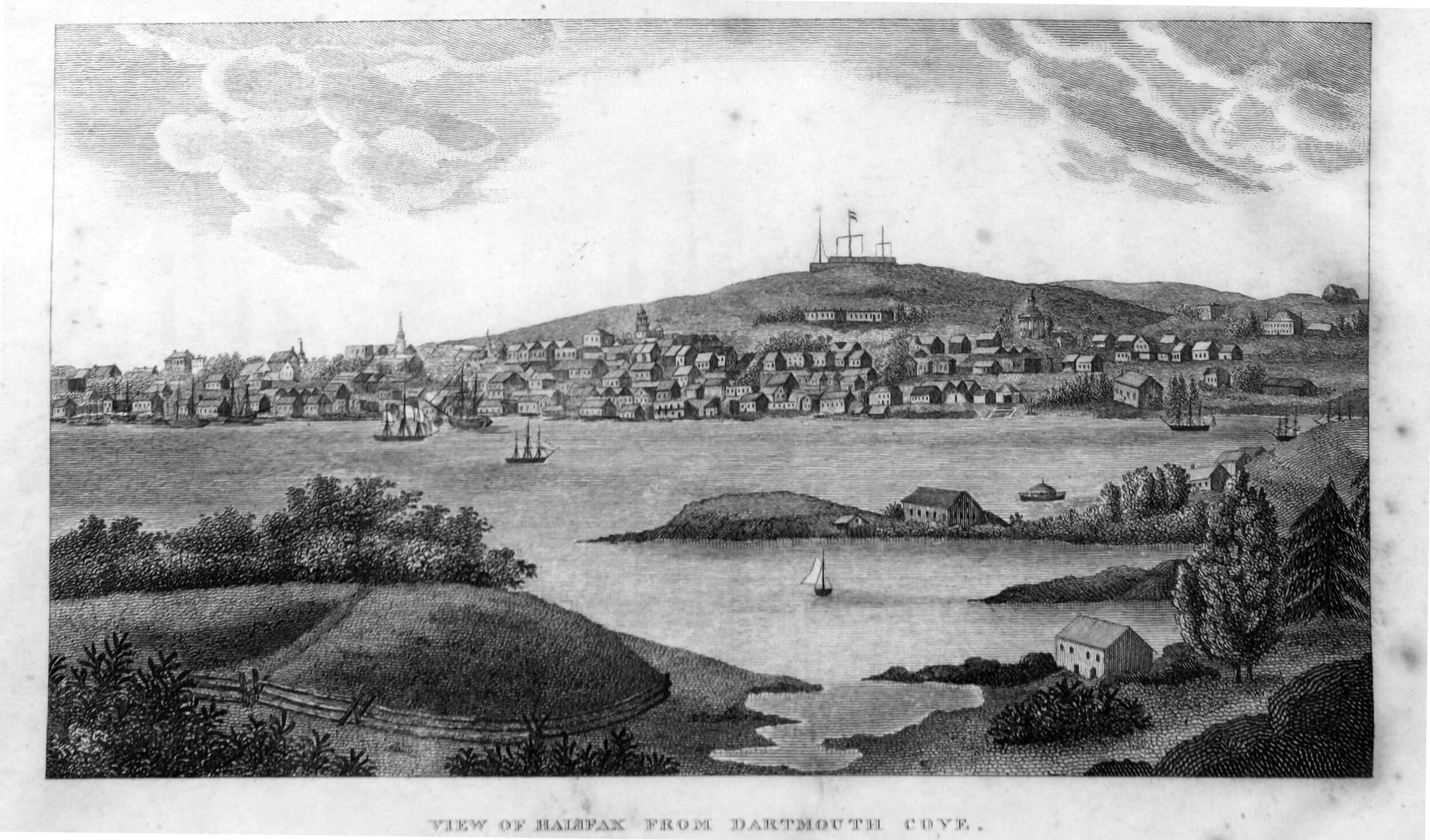

“Dartmouth – Opposite at Halifax, on the eastern side of the harbour, which is there about nine tenths of a mile wide, is situated the town of Dartmouth, which was laid out and settled in the year 1750. In the war of 1756, the [Mi’kmaq] collected in great force on the Bason of the Minas, ascended the Shubenacadie river in their canoes, and at night, surprising the guard, scalped or carried away most of the inhabitants. From this period, settlement was almost derelict, till Governor Parr, in 1784, encouraged 20 families to remove thither from Nantucket, to carry on the south sea fishery. The town was laid out in a new form, and £1,500 provided for the inhabitants to erect buildings. The spirit and activity of the new settlers created the most flattering expectations of success. Unfortunately, in 1792, the failure of a house in Halifax, extensively concerned in the whale fishery, gave a severe check to the Dartmouth establishment, which was soon after totally ruined. About this period, an agent was employed by the merchants of Milford, in England, to persuade the Nantucket settlers to remove thither; the offers were too liberal to be rejected, and the Province lost these orderly and industrious people.

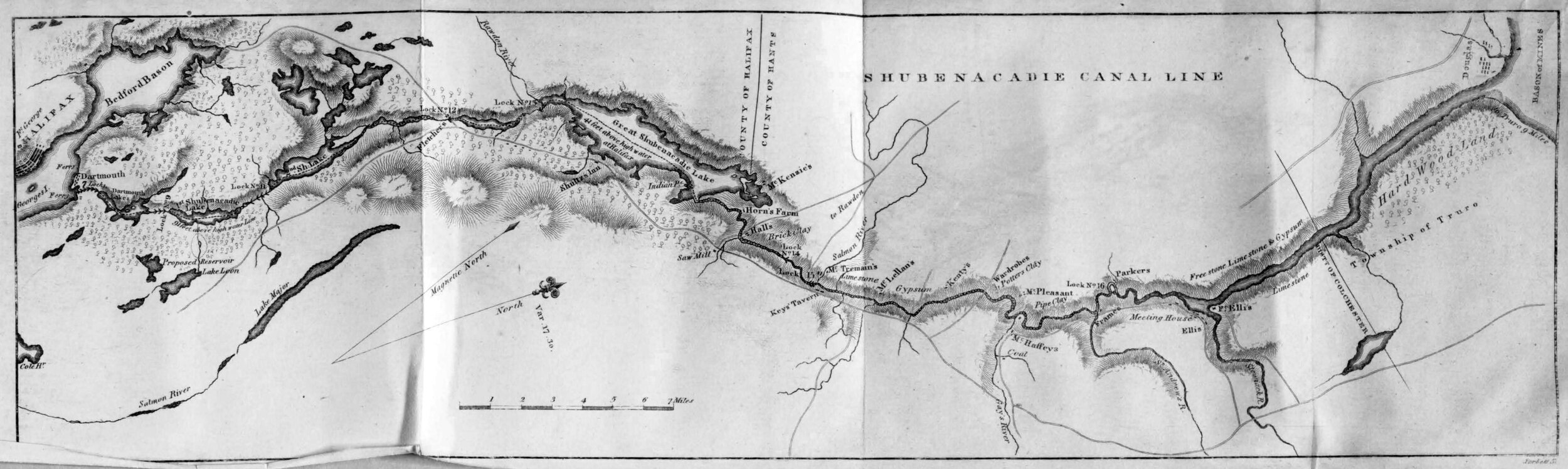

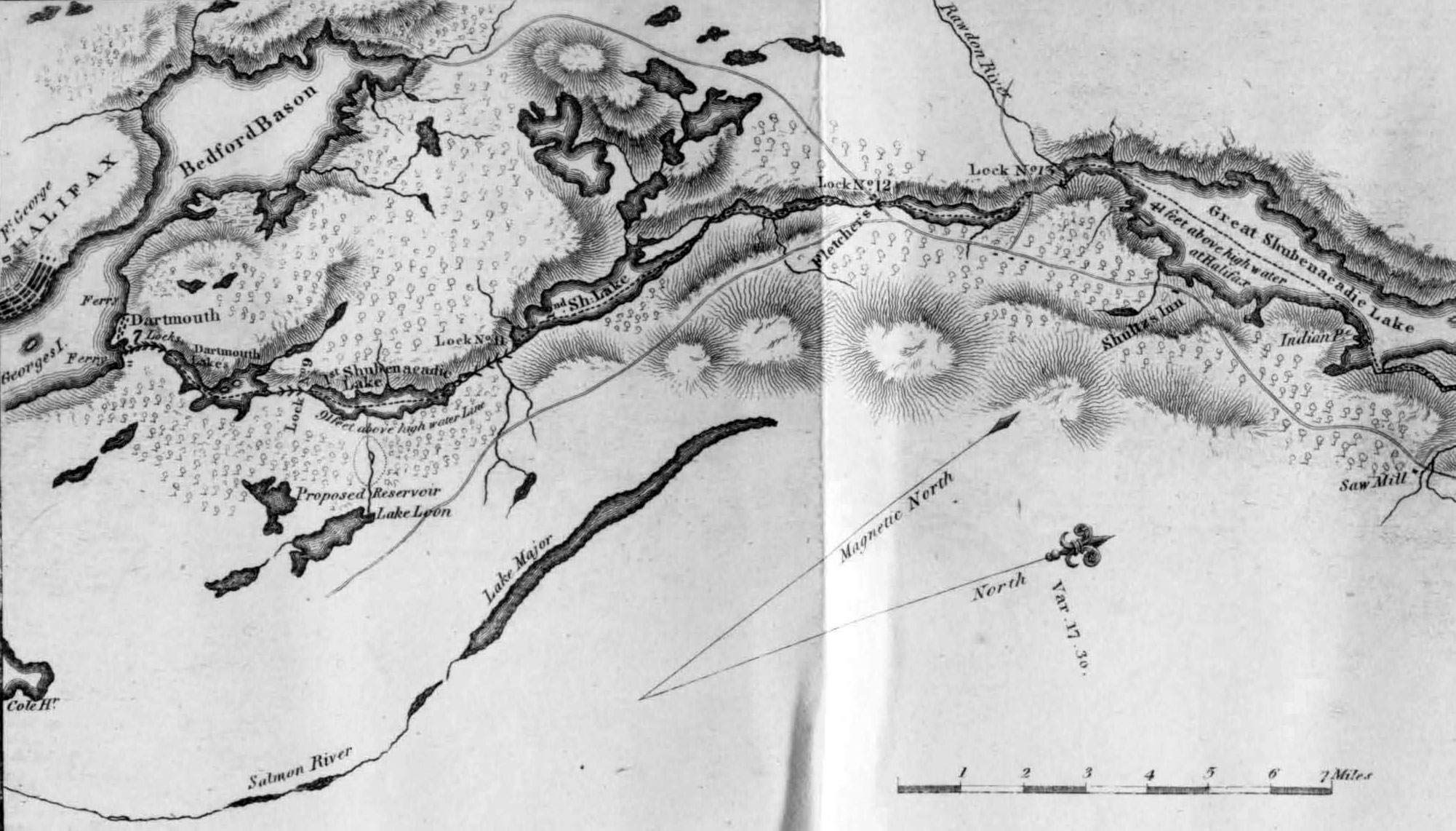

During the late war the harbour became the general rendezvous of the navy and their prizes, which materially enriched the place, and extended the number of buildings. Between Dartmouth and Halifax a team boat constantly plies, for the accommodation of passengers. The whole of the eastern shore of the harbour, though by no means the first quality of soil, is much superior to the western… On the eastern passage there are some fine farms, chiefly settled by Germans, and every cove and indent contains a few families of fisherman, who supply Halifax with fresh and cured fish. A chain of lakes in this township, connected with the source of the Shubenacadie River, suggested the idea of uniting the waters of the Bason of Minas with Halifax harbour, by means of a canal. Of these lakes Charles, or the first Shubenacadie Lake, is distant from Halifax about three miles and a half.”

Chapter V:

Various kinds of Colonial Governments—Power of Governor—Nature of Council—Jurisdiction and power of House of Assembly—Court of Chancery—Court of Error—Supreme Court—Inferior Courts of Common Pleas—Courts of General Sessions—Justices Courts—Probate Courts—Sheriff and Prothonotary—Court of Vice Admiralty—Court for the trial of Piracies—General observations on the laws of Nova-Scotia

“A desire to know something of the Government under which we live is not only natural but commendable. In England there are many books written on the constitution of the Country, but in Nova Scotia, the inquisitive reader, while he finds enacted laws, will search in vain for any work professedly treating the origin of the authority that enacts them. The labor of examining the History of other colonies analogous to our own for this information is very great, and the means of doing so not always attainable. In a work of this kind, a brief outline is all that can be looked for, consistently with the space claimed by the other objects which it embraces; but it is hoped that it will be sufficient for the purpose of general information.

In British America there were originally several kinds of Governments, but they have been generally classed under three heads.

- 1st. Proprietary governments, granted by the Crown to individuals, in the nature of feudatory principalities, with all the inferior regalities and feudatory powers of Legislation, which formerly belonged to Counties Palantine, on condition that the object for which the grant was made should be substantially pursued, and that nothing should be attempted in derogation of the authority of the King of England. Of this kind were Pennsylvania, Maryland and Carolina (now Louisiana.)

- 2nd. Charter Governments, in the nature of civil corporations, with the power of making bye laws, for their own internal regulations, and with such rights and authorities as were especially given to them in their several acts of incorporation. The only charter Governments that remained at the commencement of the Civil War, were the Colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, Providence and Connecticut.

- 3rd. Provincial governments, the constitutions of which depended on the respective Commissions, issued by the Crown to the governors, and the instructions which accompanied those commissions -Under this authority Provincial Assemblies were constituted, with the power of making local ordinances not repugnant to the laws of England. Of the latter kind is Nova Scotia, which is sometimes called the Province and sometimes the Colony of Nova Scotia. For some time previous to the Revolution in America, the popular leaders affected to call the Provincial establishments, or King’s governments on the Continent, Colonies instead of Provinces, from an opinion they had conceived that the word Province implied a conquered Country. But whatever distinction there might once have been between the terms Province, Colony and Plantation, there seems now to be none whatever, and they are indiscriminately used in several acts of Parliament. A Provincial government is immediately dependent upon the Crown, and the King remains sovereign of the Country. He appoints the Governor and Officers of State, and the people elect the Representatives as in England. The orders of judicature in these establishments are similar to those of the mother country, and their legislatures consist of a governor, representing the crown, a council or upper house, and an assembly chosen by, and representing the people at large. The following is a short account of the powers and privileges exercised in Nova-Scotia, by these several branches respectively in their own systems:

Governor

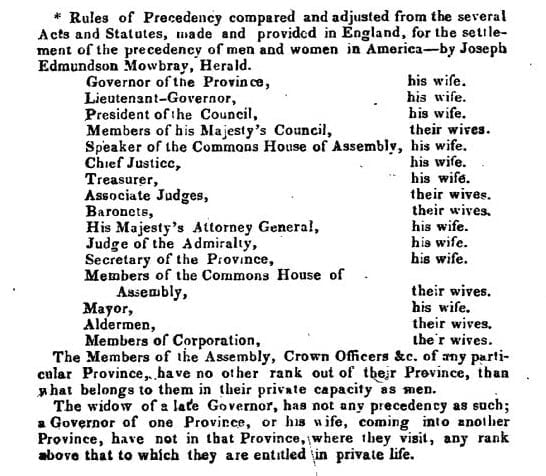

The Provinces in British North America are in general comprised in one command, and the Captain General, Governor and Commander-in-Chief, resides in Canada. The Governors of the several Provinces are styled Lieutenant-Governors, and have the title of Excellency, in consequence of being the King’s immediate Representative. The Governor of Nova- Scotia has the rank of Lieut.-General, and is styled “Lieutenant-Governor and Commander-in-Chief, in and over His Majesty’s Province of Nova-Scotia, and its dependencies, Chancellor and Vice-Admiral of the same”.

He is invested with the following powers:

- 1st. As Commander-in-Chief he has the actual command of all the militia, and if a senior military officer, of all the army within his Government; and he commissions all officers of the militia. He appoints the Judges of all the different Courts of Common Law, he nominates and supersedes at will, the Custodes, Justices of the Peace, and other subordinate civil officers. With the advice of his Council he has authority to summon General Assemblies, which he may, from time to time, prorogue and dissolve as he alone shall judge needful. All such civil employments as the Crown does not dispose or are part of his patronage, and whenever vacancies happen in such offices as are usually filled up by the British Government, the Governor appoints pro-tempore, and the persons so appointed are entitled to all the emoluments till those who are nominated to supercede them arrive in the Colony. He has likewise authority, when he shall judge any offender in criminal matters a fit object of mercy, to extend the King’s pardon towards him, except in case of murder and high treason, and even in those cases he is permitted to reprieve until the signification of the Royal Pleasure.

- 2d. The Governor has the custody of the Great Seal, presides in the High Court of Chancery, and in general exercises, within his jurisdiction, the same extensive powers as are possessed by the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, with the exception of those given by particular statutes.

- 3d. The Governor has the power of granting probate of wills and administration of the effects of persons dying intestate, and, by statute, grants licences for marriages.

- 4th. He presides in the Court of Error, of which he and the Council are Judges,to hear and determine all appeals, in the nature of writs of error, from the Superior Courts of Common Law.

- 5th. The Governor is also Vice-Admiral within his Government, although he cannot, as such, issue his warrant to the Judge of the Court of Vice-Admiralty to grant commissions to privateers.

- 6th. The Governor, besides various emoluments which arise from fees and forfeitures, has an honorable annual provision settled upon him, for the whole term of his administration in the Colony ; and that he may not be tempted to diminish the dignity of his station by improper condescensions, to leading men in the Assembly, he is in general restrained by his instructions from accepting any salary, unless the same be settled upon him by Law within the space of one year after his entrance into the Government, and expressly made irrevocable during the whole term of his residence in the administration, which appears to be a wise and necessary restriction.

A Governor, on his arrival in the Province, must (agreeably to the directions of his commission and his instructions – The Gazette has, in some instances, been held sufficient, when the Commission was not made out) in the first place, cause his commission as Governor and Commander-in-Chief, and also of Vice-Admiral, to be read and published at the first meeting of the Council, and also in such other manner as hath been usually observed on such occasions. In the next place, he must take the oaths to Government, and administer the same to each of the Council, and make and subscribe the declaration against transubstantiation, and cause the Council, unless they have previously done so, to do the same. He must then take the oath, for the due execution of the office and trust of Commander-in-Chief and Governor, and for the due and impartial administration of Justice; and he must also cause the oath of office to be administered to the Members of the Council.

— In the last place, he must take an oath to do his utmost, that the several laws relating to trade and the plantations be duly observed; which oaths and declaration, the Council, or any three of the members thereof, are empowered to administer.

Every Governor, together with his commission, receives a large body of instructions, for his guidance in the discharge of his various duties. In the event of his death, the next senior Counsellor, not being the Chief Justice or a Judge, takes the command of the Colony, until an appointment is made by His Majesty, and is required to take the same oaths, and make the same declaration as a Governor. Such are the powers and duties of a Governor, and the mode of redress for the violation of these duties, or any injuries committed by him upon the people, is prescribed with equal care. The party complaining has his choice of three modes

- 1st. by application to Parliament.

- 2d. by complaint to the Privy Council.

- 3d. by action in the King’s Bench.

By statute 11 and 12th, William 3d, cap. 12, confirmed and extended by 42d Geo. 3d, cap. 85, all offences committed by Governors of plantations, or any other persons in the execution of their offices, in any public service abroad, may be prosecuted in the Court of King’s Bench in England. The indictment is to be laid in Middlesex, and the offenders are punishable, as if the offence had been committed in England, and are also incapacitated from holding any office under the Crown. The Court of King’s Bench is empowered to award a mandamus to any Court of Judicature, or to the Governor of the Colony, where the offence was committed, to obtain proof of the matter alleged, and the evidence is to be transmitted back to that Court, and admitted upon the trial.

The Council

The Council consists of twelve members, who arc appointed either by being named in the Governor’s instructions, by mandamus (A nomination by a Governor must be followed by a mandamus, but the person nominated acts until his mandamus arrives) or by the Governor. Their privileges, powers, and office, are as follow:

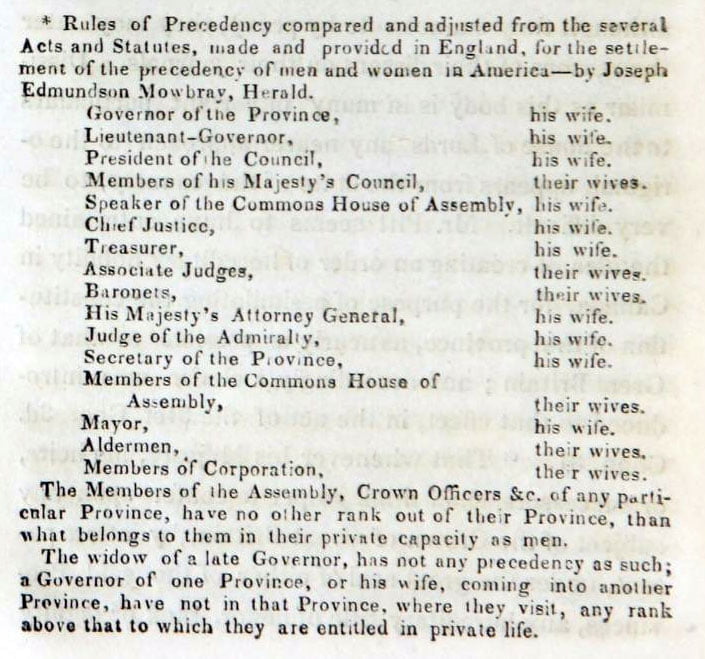

- 1st. They are severally styled Honorable, they take precedency, next to the Commander in-Chief, and on his death or absence, the eldest member succeeds to the government,under the title of President.

- 2d. They are a Council of State, the Governor or Commander-in-Chief, presiding in person, to whom they stand nearly in the same relation as the Privy Council in Great Britain does to the Sovereign.

- 3d. They are named, in every commission of the peace, as Justices throughout the province.

- 4th. The Council together with the Governor, sit as Judges in the Court of error, or Court of appeal, in civil causes, from the courts of Record, and constitute also a Court of Marriage and Divorce. It has, however, been lately decided, that if the Governor dissent from the Judgment of the Council or be in the minority, the judgment is nevertheless valid.

- 5th. The Council is a constituent part of the legislature, as their consent is necessary to the enacting of Laws. In this capacity of legislators, they sit as the upper house, distinct from the Governor, and enter protests on their journals, after the manner of the House of Peers, and are attended by their Chaplain, Clerk, &c. As there was no order of hereditary nobility in the Colonies, out of which to constitute an intermediate body, like the Peers of England and Ireland, a legislative authority was doubtless, at an early period intrusted to the Governors and their Council acting conjointly, and forming a middle branch, between the Crown on the one hand, and the representatives of the people on the other. That this was formerly the case, the history of most of the colonies clearly evinces.

(In the Saxon times the Parliament did not consist of two distinct houses, the Peers being freeholders of large territory, were deemed the hereditary representatives of their vassals and tenants. In the Scotch Parliament there ever was one House, consisting of three estates, Peers, Representatives of Shires, and commissioners of Boroughs, they all voted together indifferently, but in Committees and the like, the proportion of Committee-men from each was limited).

The governor and council in legislative affairs, constitutes not two separate and distinct bodies independent of each other, but one constituent branch only, sitting and deliberating together. As it sometimes became necessary to reject popular bills, the Governors to divert the displeasure of the assembly from themselves to the Council, gradually declined attending on such occasions, leaving it to the board to settle matters as they could, without their interference. The council readily concurred with their designs, because their absence, removing a restraint, gave them the appearance of a distinct independent estate, and the crown perceiving the utility of the measure, gradually confirmed the practice in most of the British Colonies. This appears to be the plain origin which the Council enjoy of deliberating apart from the governors, on all bills sent up by the Assembly, of proposing amendments, to such bills, or of rejecting them entirely, without the concurrence of the governor.

The Councillors serve his Majesty without salary. In the grant of all patents, the Governor is bound to consult them, and they cannot regularly pass the seal without their advice. Though they deliberate as a distinct body, in their capacity as legislators, yet as a privy council, they are always convened by the Governor, who is present at their deliberations. As an upper house, their proceedings, though conducted with closed doors, are formal, and in imitation of the usage of the house of Lords, and although they cannot vote by proxy, they may enter the reasons of their dissent on their journals. Dissimilar as this body is in many important particulars to the house of Lords, any nearer approach to the original, appears from the state of the country, to be very difficult.

Mr. Pitt seems to have entertained the idea of creating an order of hereditary nobility in Canada, for the purpose of assimilating the constitution of that province, as nearly as possible to that of Great Britain; and accordingly a clause was introduced to that effect, in the act of the 31st. Geo. 3d. Chap. 31. “That whenever his Majesty, his heirs, or successors, shall think proper to confer upon any subject of the Crown of Great Britain, by letters patent, under the great seal of either of the said Provinces, any hereditary title of honor, rank or dignity of such Province descendable* according” to any course of descent therein limited, it shall and may be lawful for his Majesty, his heirs, or successors, to annex thereto, by the said letters patent of his Majesty, his heirs or successors, shall think fit an hereditary right of being summoned to the Legislative Council of such Province, descendable according to the course of descent so limited, with respect to such title rank or dignity, and that every person on whom such right shall be conferred, or to whom such right shall severally so descend, shall be entitled to demand of the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, or Commander-in-Chief, or person administering the government of such province, his writ of summons to such Legislative Council, at any town, after he shall have attained the age of twenty one years, subject nevertheless to the provisions hereinafter contained.”

This power has never been exercised: it has been justly observed, that these honors might be very proper, and of great utility in countries where they have existed by long custom, but they are not fit to be introduced where they have no original existence; where there is no particular reason for introducing them, arising from the nature of the country, its extent, its state of improvement or its peculiar customs; and where instead of attracting respect they might excite envy. Lords, it was said, might be given to the Colonies, but there was no such thing as creating that reserve and respect for them, on which their dignity and weight in the view of both the popular and monarchical part of the Constitution depended, and which could alone give them that power of controul and support, which were the objects of their institution.

But although the introduction of titles is not desirable, this board is susceptible of great improvement, by a total separation of its duties as a Privy Council, and a branch of the Legislature. Experiments of all kinds in Government are undoubtedly much to be deprecated, but this plan has been adopted elsewhere, not only with safety but with mutual advantage to the interests of the Crown and the people. By making the Members of the Legislative Council independent of the Governor for their existence, (for at present he has not only the power of nomination, but of suspension – Stokes mentions an instance of a Governor of a Colony, suspending a Councillor, on the singular ground of having married his daughter without his consent) and investing them with no other powers than those necessary to a branch of the Legislature, much weight would be added to administration, on the confidence and extent of interest that it would thereby obtain, a much more perfect and political distribution of power would be given to the Legislature, and the strange anomaly avoided of the same persons passing a law, and then sitting in judgement on their own act, and advising the Governor to assent to it.

This could be effected in two ways, by making the Legislative Council elective, or leaving the nomination to the Crown. If the former were preferred, it could be constructed on the plan proposed by Mr. Fox, in his speech in Parliament on the Quebec Bill. He suggested that the Members of the Council should not be eligible to be elected, unless they possessed qualifications infinitely higher than those who were eligible to be chosen members of the House of Assembly, and in the like manner, that the electors of the members of the Council, should possess qualifications, also proportionally higher than those of the electors of Representatives. By this means this country would have a real aristocracy chosen from among persons of the highest property, by people possessed of large landed estate, who would thus necessarily have the weight, influence, and independency, from which alone can be derived a power of guarding against any innovations which might be made either by the people on the one side, or the Crown on the other; should this mode be objected to, as bordering too much on democracy, the election might be left with great safety to the Crown, with this express proviso, that every Councillor so named, should be possessed of landed estate in the Colony, to a certain given extent, and should hold his seat for life. In either mode it would be rendered a most respectable and useful body.

Whether the Council forms a Court for the trial of offences, by impeachment from the House of Assembly, upon analogy to the practice of Parliament, is a question which never having been agitated here, has not been judicially determined. As Councillors do not represent any particular body of people, like the House of Lords, nor assemble as hereditary Legislators, in support of their rights and dignities, equally independent of the Crown and the people, but are appointed at the discretion of the Governor (In 1791, the articles of impeachment against the Judges of Nova-Scotia, were ordered to be heard before the King in Council), it seems very questionable whether they possess the power. The reason assigned in England, for the peculiar propriety of prosecuting high crimes and misdemeanors, by impeachment, is that as the Constituents of the Commons, are the parties generally injured, they cannot judge with impartiality, and therefore prefer their accusations before the other branch, which consists of the nobility, who have neither the same interest nor the same passions as popular assemblies. This distinction not being so obvious in the Colonial Legislatures, it appears that a complaint in the nature of impeachment, should be addressed to the King in Council.

House Of Assembly

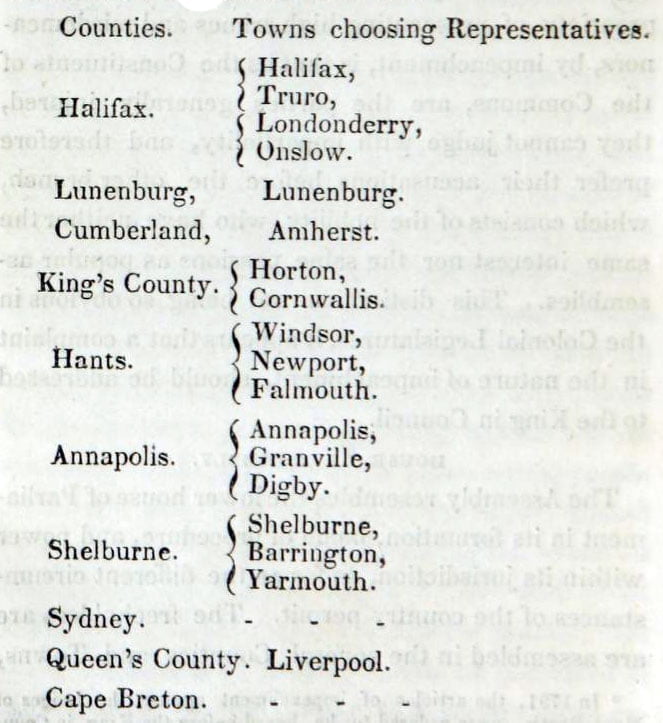

The Assembly resembles the lower house of Parliament in its formation, mode of procedure, and power within its jurisdiction, as far as the different circumstances of the country permit. The freeholders are are assembled in the several Counties and Towns entitled to representation by the king’s writ, and their suffrages taken by the Sheriff. The members thus elected, are required by the Governor to meet at Halifax, the capital of the province, at a certain day, when the usual oaths being administered, and a Speaker chosen and approved, the sessions is opened by a speech from the person administering the Government, in imitation of that usually delivered from the throne, in which after adverting to the state of the Province, he calls their attention to such local subjects, as seem to require their immediate consideration. Halifax chooses 4 county, and 2 town, members; all the other counties 2, and the towns mentioned in the subjoined Table one.

The qualifications for a vote or representation are either a yearly income of forty shillings, derived from real estate within the particular county or town for which the election is held, or a title in fee simple of a dwelling house, and the ground on which it stands, or one hundred acres of land, five of which must be under cultivation. It is requisite that the title be registered six months before the test of the writ, unless it be by descent or devise. The declaration against transubstantiation has hitherto proved an effectual bar to the admission of Catholics into the Assembly, but upon the re-annexation of Cape-Breton to the Government of the Province, a gentleman professing that faith was returned as a member for the Island, and a dispensation procured from his Majesty, for administering the declaration to him.

—When this was made known, the Assembly, after much debate, adopted the following resolution:

“Resolved, that this House, grateful to his Majesty for relieving his Roman Catholic subjects from the disability they were heretofore under, from sitting- in this House, do admit the said Lawrence Kavanagh to take his seat, and will in future permit Roman Catholics, who may be duly elected, and shall have the necessary qualifications for a seat in this House, to take such seat without making a declaration against popery and transubstantiation; and that a Committee be appointed to wait upon his Excellency the Governor, and communicate to him the Resolution of this House.”

In 1827, an address was voted to his Majesty, by the unanimous voice of the House, praying for the total removal of this obnoxious test, as far as regarded his Catholic subjects of Nova Scotia. The Assembly continues for the term of seven years, from the return day of the writs of election, subject nevertheless to be dissolved in the mean time by the Governor, who has the power of proroguing the Council and Assembly, and appointing the time and place of their Session; with this constitutional injunction, that they shall be called together once at least every year.

The Legislature meets generally in winter, and continues in Session from six to twelve weeks. The principal business consists in investigating the public accounts; in appropriating the Revenue; which, after the discharging of the civil list, is chiefly applied to the improvement of the roads and bridges, bounties for the encouragement of agriculture; and sometimes for promoting the fisheries. As its jurisdiction is confined to the limits of the Province, and as there are no direct taxes in the Country (poor and county rates and statute labour excepted) the above mentioned business, together with some few Laws, principally of a local nature, usually occupies their attention. Sometimes however, business of a more general interest comes before them, when the debates are often conducted with ability and spirit. In treating of the Assembly, it will be proper to investigate the origin of the claim of the Colonists to legislate for themselves; and to unfold the principles in which this claim was confirmed by the Mother Country.

—The constitution of England, as it stood at the discovery of America, had nothing in its nature providing for Colonies. They have therefore, at different periods of their growth, experienced very different treatment. At first they were considered lauds without the limits of the realm, and therefore, not being united to it, not the property of the Realm: as the people who settled upon these lands in partibus exteris, were liege subjects, the King assumed the right of property and Government, to the preclusion of the jurisdiction of the state. He called them his foreign dominions, his possessions abroad, not parts and parcels of the Realm, and “as not yet annexed to the crown.”

It was upon this principle, that in the year 1621, when the Commons asserted the right of Parliament to a jurisdiction over them, by attempting to pass a bill for establishing a free fishery on the coasts of Virginia, New England, and Newfoundland, they were told by the servants of the crown that it was not fit for them to make laws for those countries which were not yet annexed to the crown, and that the bill was not proper for that house, as it concerned America. Upon this assumption the Colonies were settled by the King’s license, and the Governments established by Royal Charters; while the people emigrating to the Provinces considered themselves out of the realm; and in their executive and legislative capacities, in immediate connection with the King as their only Sovereign Lord. These novel possessions requiring some form of government, it became an exceedingly difficult matter to select that form. At last an analogy was supposed to exist between the Colonies and the Dutchy of Normandy; and the same form of Government* was adopted as had been used for the Island of Jersey.

*It is however observable, that although it was evidently the intention of the mother country, to grant the power of election to the people of the Colonies, so soon as they should be in a situation to receive a representative form of Government, yet the people assumed the right themselves, as appears by the following extract from Hutchinson, 1 vol. 94. ‘”Virginia had been many years distracted, under the government of Presidents and Governors, with Councils, in whose nomination or removal of the people had no voice until in the year 1620, a house of Burgesses broke out in the Colony, the King nor the grand Council at home, not having given any powers or direction for it. The Governor and assistants of the Massachusetts, at first intended to rule the people, but this lasted two or three years only, and although there is no colour for it in the Charter, yet a house of deputies appeared suddenly in 1634, to the surprise of the Magistrates, and the disappointment of their schemes of power. Connecticut soon after followed the plan of Massachusetts. New Haven, although the people had the highest reverence for their leaders, yet on matters of legislation the people, from the beginning, would have their share by their representatives. New Hampshire, combined together under the same form with Massachusetts. Barbadoes or the Leeward Islands began in 1625, struggled under Governors and Councils, and contending proprietors, 20 years. At length in 1645, an Assembly was called and the only reason given was, that by the grant to the Earl of Carlisle, the inhabitants were to have all the liberties, privileges and franchises of English subjects. After the restoration, there is no instance on the American continent, of a colony settled without a representation of the people, nor any attempt to deprive the colonies of this privilege, except in the arbitrary reign of King James the 2d.

It was a most fortunate circumstance, that the Island had by its constitution, “a right to hold a convention or meeting of the three orders of the Islands, in imitation of those august bodies in great kingdoms, a shadow and resemblance of an English Parliament.”

The King having assumed a right to govern the Colonies, without the intervention of Parliament, so the two Houses of Lords and Commons, in the year 1643, exerted the same power, without the concurrence of the King. They appointed the Earl of Warwick Governor in Chief of all the Plantations of America,created a committee for their regulation, and passed several laws concerning them. (See Pownal on the Colonies, passim)

Upon the restoration of Monarchy, the constitution of the Colonies received a great change. Parliament asserted, that all His Majesty’s Foreign Dominions were part of the realm, and then, for the first time, in their proper capacity, interposed in the regulation and government of the Colonies. From that period sundry laws have been passed, regulating their commerce, and having, in other respects, a direct operation on the Colonies. But nothing emanating either from the power assumed by the King, independent of Parliament, or from the Parliament without the concurrence of the King, or from the union of both, establishing the right of legislation in the colonists. It may be asserted, that every British subject has an essential right to the enjoyment of such a form of government, as secures the unrestrained exercise of all those powers necessary for the preservation of his freedom and his rights, according to the constitution of England; and that no authority can contract it within a narrower compass than the subject is entitled to by the Great Charter. Hence the Charters and Proclamations of the Crown to the several Colonies, are considered as declaratory only of ancient rights, and not creative of new privileges.

It is worthy of remark, that when England was herself a Province, the Colonies of London, Colchester, &c. enjoyed the same privilege of being governed by a legislative magistracy, which the American Colonies always contended for. At a subsequent period, but before the discovery of the New World, and when the precedent was considered as not likely to be often followed, we find that when King Edward ordered the French inhabitants to leave Calais, and planted an English Colony there, that place sent Burgesses to Parliament.

To all this it has often been answered, that the Colonies are virtually represented in Parliament. A few words will suffice in reply to this position. It was well observed by the Earl of Chatham, (although he carried the doctrine of the power of Parliament over the Colonies, to every circumstance of legislation and government short of taxation) “that the idea of virtual representation, as regards America, is the most contemptible that ever entered the head of man.” Of England it is entirely true.

Although copyholders and even freeholders, within the precincts of boroughs (not being burgesses) have no vote, yet the property of the copy-holders is represented by its lord, and the property of the borough is represented by the corporation, who choose the member of Parliament; while those persons who are not actually freeholders, have the option of becoming so if they think proper. But the Colonies are neither within any county or borough of England. Few members of Parliament have ever seen them, and none have a very perfect knowledge of them. They can therefore neither be said to be actually, or virtually represented, in that august body.

Hence the Colonies have a right, either to a legislature of their own, or to participate in that of Great-Britain. To the latter there are many objections; and when suggested on a former occasion, the plan was not cordially received on either side of the water; the other, custom has sanctioned and experience approved. To what extent the British Parliament has a right to interpose its authority, or how far the power of the Colonial Assembly extends, it is impossible to ascertain with accuracy. The doctrine of the omnipotence of the one, and the independence of the other, has at different times been pushed to an extreme by the advocates of each.

The true distinction appears to be, that Parliament is supreme in all external, and the Colonial Assembly in all internal matters. The unalterable right of property has been guaranteed to the Colonists, by the act renouncing the claim of taxation, the 18th Geo. 3d, by which it is declared “that the King and Parliament of Great Britain will not impose any duty, tax, or assessment, whether payable in any of his Majesty’s Colonies, Provinces or Plantations, in North America or the West Indies, except such duties as it may be expedient to impose, for the regulation of commerce; the net produce of such duties to be always paid and applied to, and for the use of the Colony, Province or Plantation, in which the same shall be respectively levied, in such manner as other duties, collected by the authority of the respective General Courts or General Assemblies of such Colonies, Provinces or Plantations, are ordinarily paid and applies.

Taxation is ours, commercial regulation is theirs; this distinction, says a distinguished statesman, is involved in the abstract nature of things. Property is private, individual, abstract; and it is contrary to the principles of natural and civil liberty, that a man should be divested of any part of his property without his consent. Trade is a complicated and extended consideration; to regulate the numberless movements of its several parts, and to combine them in one harmonious effect for the good of the whole, requires the superintending wisdom and energy of the supreme power of the Empire.

—The Colonist acknowledges this supremacy in all things, with the exception of taxation and of legislation in those matters of internal Government to which the Local Assemblies are competent. This may be said to be the “quam ultra contraque nequit consistere rectum.” But ever in matters of a local nature the regal control is well secured by the negative of the Governor; by his standing instructions not to give his assent to any law of a doubtful nature without a clause suspending its operation, until his Majesty’s pleasure be known, and by the power assumed and exercised, if disagreeing to any law within three years after it has passed the Colonial Legislature.

With these Provinces it is absurd to suppose, whatever may be said to the contrary, that the Local Assemblies are not supreme within their own jurisdiction; or that a people can be subject to two different Legislatures; exercising at the same time equal powers yet not communicating with each other, nor from their situation capable of being privy to each others proceedings. This whole state of commercial servitude and civil liberty when taken together, says Mr. Burke, is certainly not perfect freedom, but comparing it with the ordinary circumstances of human nature, a happy and liberal condition.

Court Of Chancery

The Governor is Chancellor in Office. The union of these two offices is filled with difficulties, and where the Governor is, as has been the case in almost all the Colonies of late years, a military man, they seem wholly incompatible. Mr. Pownal, a gentleman of great experience in colonial affairs, having been Governor of Massachusetts, South Carolina and New Jersey, thus expresses himself on this subject: “How unfit are Governors in general for this high office of law, and how improper it is, that they should be Judges, where perhaps the consequence of judgment may involve Government and the administration thereof, in the contentions of parties.— Indeed the fact is, that the general diffidence of the wisdom of this Court, thus constituted, the apprehension that reasons of state may be mingled with the grounds of the judgment, have had an effect that the coming to this Court is avoided as much as possible, so that it is almost in disuse, where the establishment of it is allowed.”

The Court of Chancery in this Colony, has never been conducted in a manner to create the dissatisfaction alluded to in other Provinces; but the increased business of the Court, the delicate nature of the appointment, and the difficulties attending the situation, induced our late Lieutenant Governor, Sir James Kempt, to request his Majesty’s Ministers to appoint a professional man, to fill the situation of the Master of the Rolls, and the Solicitor General has been appointed to that office, with a Provincial salary of £600 a year. This is the first appointment of the kind ever made in the Colonies. It may be still doubted, whether it would not have been more advantageous and convenient to the country at large, to have abolished the Court altogether, and to have empowered the Judges of the King’s Bench to sit as Judges in Equity, at stated and different terms from those of the Common Law Courts. The nature of the Court, as at present constituted, admits of great delays. An appeal lies from an interlocutory decretal order of a Chancellor to His Majesty in Council, and so toties quoties, by means of which the proceedings may be protracted by a litigious person to an indefinite length. The unnecessary prolixity of pleadings, which characterises the Chancery at home, has been introduced into practice here, and the expence and delay incidental to its proceedings, arc not at all calculated for the exigencies and means of the country.

Court Of Error And Appeals

The Governor and Council, conjointly, constitute a Court of Error, from which an appeal lies in the dernier resort to the King in Council. At the time of settling the Colonies, there was no precedent of a Judicatory besides those within the realm, except in the cases of Guernsey and Jersey. These remnants of the Dutchy of Normandy were not, according to the prevailing doctrine of those times, within the realm. According to the custom in Normandy, appeals lay to the Duke in Council; and upon the general precedent (without, perhaps, adverting to the peculiarity of the appeal, lying to the Duke of Normandy, and not to the King) was an appeal established from the Courts in the Colony to the King in Council. An appeal is under the following restrictions :

- 1st. No appeal shall be allowed to the Governor in Council, in any civil cause, unless the debtor damage, or the sum or value appealed for, do exceed the sum of £300 sterling, except the matter in question relates to the taking or demanding any duty payable to the King, or to any fee of office, or annual rent, or other such-like matter or thing, where his rights in future may be bound ; in all which cases an appeal is admitted to the King, in his Privy Council, though the sum or value appealed for, be of less value. In all cases of fines for misdemeanours, no appeals are admitted to the King in Council, except the fines, so imposed, amount to or exceed the value of £200 sterling.

- 2d. That every such appeal to the Governor in Council be made within fourteen days after Judgment or sentence is pronounced in the Court below ; and that the appellant or plaintiff in error, do give good security that he will effectually prosecute his appeal or writ of error, and answer the condemnation money, and also pay such costs and damages as shall be awarded, in case the judgment or sentence of the Court below shall be affirmed.

- 3d. That no appeal be allowed from the judgment or sentence of the Governor in Council, or from the decree of the Court of Chancery, to the King in his Council, unless the debt, damages, or the sum or value so appealed for, do exceed the sum of £500 sterling, except where the matter in question relates to the taking or demanding any duty payable to the King, or to any fee of office, or an annual rent, as above mentioned.

- 4th. That such appeal to His Majesty or his Privy Council, be made within fourteen days after judgment or sentence is pronounced by the Governor, in the Court of Chancery ; and that the appellant or plaintiff in error, do give good security, that he will effectually prosecute his appeal or writ of error, and answer the condemnation money ; and also pay such costs and damages as shall be awarded by his Majesty, in case the sentence of the Governor in Council, or decree of the Court of Chancery, be affirmed. There is no appeal allowed in criminal causes.

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is invested with the powers of the King’s Bench, Common Pleas, and Exchequer. It is composed of a Chief Justice, three Assistants and a Circuit Associate. The Chief Justice receives from the English Government an annual salary oi £800 sterling, in addition to which he receives fees to a large amount. The assistants are paid by the Province, and are entitled, under a permanent act, to £600 a year, and a guinea a day additional, when travelling. This Court has a jurisdiction extending over the whole Province, including Cape Breton, in all matters criminal and civil; but cannot try any actions for the collection of debts, when the whole amount of dealings do not exceed five pounds, except on appeal, or when the parties reside in different counties. It sets four times a year at Halifax, and has two Circuits on the eastern and western districts —one at Cape Breton, and one on the south shore. The venerable Chief Justice, Hon. S.S. Blowers, has presided in this Court since the year 1798—the patient investigation which he gives every cause that is tried before him—the firmness, yet moderation of temper which he exhibits—the impartiality, integrity and profound legal knowledge, with which he dignifies the bench, have rendered him an object of affection, not only to the gentlemen of the bar, but to the public at large. Etiam contra quos statuit, tequos placates que dimisit.

The law regulating the admission of the Attorneys has been allowed to expire, and it is now governed by rule of Court. It is required, that every person applying for admission, shall have been duly articled as a clerk, to an Attorney of the Supreme Court, for the period of five years preceding such application; except graduates of King’s College, Windsor, who are eligible to admission at the expiration of four years. There is also a farther distinction made in favor of the College. The graduate signs the roll as an Attorney and Barrister at the same time, while the other student is required to practice as an Attorney for the space of one year, before he is entitled to the privileges of a Barrister. The conduct and discipline of the bar is regulated by an Institution, established in 1825, under the patronage of his Excellency Sir James Kempt, and denominated the Bar Society. It consists of the Judges of the Supreme Court and Common Pleas, the Crown Officers, and other members of the profession.

The legal acquirements of the Bench and Bar are highly respectable, but the decisions of the Court are not easily known for want of reports. There are a great variety of questions constantly arising upon our Provincial Statutes, which, from the novelty of the circumstances under which they were framed, are peculiar to the Country, and correct reports of these cases are alike important to the Judges, the Lawyers, and the public. Such a system would tend to produce an uniformity of decision, to check litigation, and to foster a laudable ambition in the Court, to administer law upon such principles of argument and construction, as may furnish rules which shall govern in all similar or analogous cases. At an early period of the Constitution of England, the reasons of a judgment were set forth in the record, but that practice has long been disused.

According to the modern practice, the greater number of important questions agitated in the Courts of Law come before them on motions for new trial; cases reserved on summary applications of different sorts. In neither of these cases does the record furnish the evidence, either of the facts, or the arguments of the Counsel and the Court, for which there is no other depositor} than reports, on the fidelity of which a great part of the Law almost entirely depends. The most ancient compilations of this sort are the year books, the works of persons appointed for that purpose. The special office of Reporter was discontinued so long ago as the reign of Henry VIII. and although, in the reign of James I., Lord Chancellor Bacon procured its revival, it was soon dropped again,and the proceedings of Westminster Hall, from that time till now, would have been lost in oblivion; had it not been for the voluntary industry of succeeding Reporters. As the demand for books of reports in the Province, would be chiefly confined to the Gentlemen of the profession, the sale of them would not only afford no remuneration for the labour of preparing them for the press, but would not even defray the expense of publication, which most unquestionably deserves to be borne by the public purse. It is hoped that the time is not far distant, when this subject will receive the attention of the Legislature, and that means will be found to remedy the evil so universally felt in the Province.

Inferior Courts Of Common Pleas

There is no separate Court of Common Pleas for the Province, but there are Courts in each County, bearing the same appellation, and resembling it in many of its powers. These Courts, when first constituted, had power to issue both mesne and final process to any part of the Province; and had a concurrent jurisdiction with the Supreme Court in all civil causes. They were held in the several counties by Magistrates, or such other persons as were deemed best qualified to fill the situation of Judges; but there was no salary attached to the office, and fees, similar in their nature, but smaller in amount than those received by the Judges of the Supreme Court, were the only remuneration given them for their trouble.

As the King’s Bench was rising in reputation, from the ability and learning of its Judges, these Courts fell into disuse, and few causes of difficulty or importance were tried in them. It was even found necessary to limit their jurisdiction, and they were restrained from issuing mesne process out of the county in which they sat. The exigencies of the county requiring them to be put into a more efficient state, a law was passed in 1824, for dividing the Province into three Districts or Circuits, and the Governor empowered to appoint unprofessional man to each Circuit, as first Justice of the several Courts of Common Pleas within the District, and also President of the Courts of Sessions. The salary provided for their appointments was £450, inclusive of travelling and other fees, while the fees previously held by the former Judges, were made payable to them as long as they continued in office. The process and course of practice is the same in the Courts of King’s Bench and Common Pleas, and the jurisdiction of both limited to five pounds. All original process is issued by the Court of common law itself, and tested in the name of the Chief Justice; and the Chancellor issues no writ whatever, whereon to found the proceeding of these Courts.

Few real actions are in use in the Colony, except actions of Dower and Partition, as all titles to land are tried either by ejectment, trespass, or replevin. The writs of mesne process are of three kinds. A summons, or order to appear and defend suit, a capias by which the Sheriffis ordered to arrest the debtor, and on which bail may be put in, as in England, and an attachment, which is a mened writ, and both summonses the party,and attaches as much property as, by appraisement, will amount to the sum sworn to. Perishable property, thus attached, if not bailed or security given for its forth-coming after judgement is immediately sold. The operation of this writ has of late been restrained to the recovery of debts existing prior to the year 1821, and to securing the effects of absent or absconding debtors. After judgment an execution is issued, which, combining the four English writs of final process, directs the Sheriff to levy the amount thereof on the goods and chattles, lands and tenements of the defendant, and in default thereof to commit him to prison.

Court Of General Sessions

This Court is similar in its constitution, powers and practice, to the Courts of Quarter Sessions in England.

Justices Court

The collection of small debts is a subject every¬ where fraught with difficulties; and various modes have been adopted at different times, with a view to combine correctness of decision in the Judge, with a diminution of the expense of collection. At present any two Magistrates are authorised to hold a Court for the trial of all actions of debt, where the whole amount of dealings is not less than three, and does not exceed five pounds. All sums under three pounds may be collected by suit before a single Justice. From the decision of these Courts, an appeal lies to the Supreme and Inferior Courts of Common Pleas.

Hitherto local influence, and the intrigues of elections, have had great weight in too many of the recommendations which have been made to the Executive, for the appointment of Justices of the Peace; and the patronage, and the little emoluments of the office, which the collection of small debts has encreased, have occasioned the commission to be eagerly sought after; and to use the words of Lord Bacon—“There are many who account it an honor to be burdened with the office of Justice of the Peace.” The proceedings in these Courts are summary, and when judgment is given, an execution issues to a constable to levy the debt and costs, in the same manner as the Sheriff proceeds on a similar writ, from the higher Courts. Whether the evils incidental to these Courts are unavoidable, or whether a better system could not be devised, is a subject well worthy of serious consideration.

Probate Courts

The Governor, in his capacity of ordinary, formerly delegated his power to the Surrogate General, who resided at Halifax, and whose jurisdiction extended over the whole Province. Since that period, Surrogates have been appointed in the several counties, and the law requires probate to be granted in the county where the testator last dwelt. There is no Provincial system of law regulating these Probate Courts, and the Judges are left to find their way by the feeble light of analogy to the Ecclesiastical Courts of England. This, perhaps, will account for the irregularity and confusion prevailing in those districts where Lawyers do not preside in these Courts. There is no branch of the jurisprudence of the country which requires revision so much as this department. The statute of distribution, of Nova Scotia, directs the estate of an intestate to be divided in the following manner:

—One third, after the payment of debts, is allotted to the widow, both of personal and real estate, the former absolutely, the latter during her life. Of the other two thirds, two shares are given to the eldest son, and the residue equally distributed between the remaining children, or such as legally represent them. If the real estate cannot be divided without great injury, the Judge of Probate is required, upon evidence thereof, to order it to be appraised, and to offer it at such appraised value to the sons of the intestate successively, who have preference according to seniority. If either of the sons take the estate at the price offered, he is bound to pay, in a given time, the proportionable shares of the purchase money to the other heirs.

— After the widow’s death, her dower in land is divided in like manner. If there be no child, the widow is entitled to a moiety of the personal estate, and a life interest in one third of the real estate ; and if there be neither wife nor child, the whole is distributed among the next of kin to the intestate, in equal degree, and their legal representatives ; but representatives among collaterals, after the children of brothers and sisters, are not admitted. Where the estate is insolvent, an equal distribution takes place among the creditors, with the exception of the King, who takes precedence of all other mortgages, and those who have obtained judgment against the debtor in his life time.

The act of distribution was founded upon that in Massachusetts, and the reason given for deviating from the course of descent in England, and assigning only two shares of the real estate to the eldest son, is, that in a new country, the improvements necessary to be made upon land, and the expence of subduing the soil, constantly absorb the whole of the personal property ; and that if the real estate were inherited by the eldest, there would be nothing left to provide for the younger children. And it is on this ground that such an essential alteration in the Law of England has been approved of by the King in Council.

Sheriff And Prothonotary

The Sheriffs of the different Counties are appointed annually by the Governor, from a list made by the Chief Justice, proposing three persons for each county for his choice. This office being lucrative is always solicited, and the Sheriff is invariably continued from year to year, so long as he discharges the duties of his situation with diligence and fidelity.

—The offices of Prothonotory and clerk of the Court, are patent appointments held by the same officer. The person now holding them, notwithstanding the law on the subject of non residence, has lived for many years in England. He has a deputy in each county, who acts as clerk of the Supreme Court and Common Pleas.

Court Of Vice Admiralty

In the year 1801 his Majesty directed the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to revoke the prize Commissions, which had been granted to the Vice Admiralty Courts in the West Indies, and in the Colonies upon the American continent, except Jamaica and Martinique. An act of Parliament was then passed, 41. Geo. 3. c. 96. by which each and every of the Vice-Admiralty Courts, established in any two of the Islands in the West Indies and at Halifax, were empowered to issue their process to any other of his Majesty’s Colonies or Territories in the West Indies or America, including therein the Bahama and Bermuda Islands, as if the Court were established in the Island, Colony or Territory, within which its Junctions were to be exercised.

His Majesty was also authorised to fix salaries for Judges, not exceeding the sum of two thousand pounds per annum for each Judge, and it was enacted that the profits and emoluments of the said Judges should in no case exceed two thousand pounds each and every year, over and above the salary. Sir Alexander Croke, L.L.D. then an advocate of the Civil Law, had the first appointment upon this new establishment at Halifax, and presided in it from that period until the termination of the American War. He had not only distinguished himself as an advocate in Doctors Commons, but his vindication of the belligerent rights of Great Britain, in his celebrated answer to Schlegel, and his introduction to the case of Horner and Lydiard, brought his talents into that notice which added a value to his judicial decisions. The causes decided in that Court have been collected, and very ably reported, by the Hon. James Stewart. As the emoluments of the office terminated with the war, the duties of the situation are performed temporally by the Chief Justice. The Court of Vice Admiralty exercises three sorts of jurisdictions.

- 1st. it is the proper Court for deciding all maritime causes.

- 2d. it is the Court for the trial of prizes taken in time of war, between Great Britain and any other state, to deter¬ mine whether they be lawful prizes or not.

- 3d. it exercises a concurrent jurisdiction with the Courts of Record in the cases of forfeiture and penalties,incurred by the breach of any act of Parliament, relating to the trade and revenue of the Colony.

The King’s Privy Council constitute a court of appeal, to which body, by 22 . Geo. 2 . c. 3. the Judges of the Court of Westminster Hall were added, with a proviso that no Judgment should be valid unless a majority of the Commissioners present were actually Privy Counsellors. In matters relating to the trade and revenues of the Colony, if the sum in question does not exceed £500 sterling, the party aggrieved must first prefer a petition to his Majesty, for leave to appeal from the judgment of this Court.

Court For The Trial Of Piracies

There is a Court of a peculiar construction established in the Colonies, for the trial of piracies. Formerly pirates were tried in England by the Court of Admiralty, which proceeded without Jury, but as the exercise of such an authority was not only repugnant to the feelings of Englishmen, but to the genius of the Laws of the country, a statute was passed in 28 Henry VIII. which enacted that all piracies, felonies and robberies, committed on the high seas, should be tried by Commissioners, to be nominated by the Lord Chancellor; the indictment being first found by a Grand Jury, and afterwards tried by a Petit Jury, and that the proceedings should be according to the Common Law.

Under this Law piracies have continued to be tried in England, but as the provisions of that statute did not extend to the Colonies, it became necessary, when offenders were apprehended in the Plantations, to send them to England, to take their trial. To remedy so great an inconvenience, the statute of William III. was passed, which enacts that all piracies, felonies and robberies,committed on the high seas, may be tried in any of the Colonies by Commissioners, to be appointed by the King’s Commission, directed to any of the Admirals, &c. and such persons, by name, for the time being, as his Majesty shall think fit; who shall have power jointly and severally to call a Court of Admiralty, which shall consist of seven persons at least, and shall proceed to the trial of said offenders.

The statute of Henry VIII. was also extended to the Colonies by the 4 Geo. I. c. 11. The mode hitherto adopted in the Colonies is, to collect the Court under the 11 and 12 of William III. and to proceed to the trial of the prisoners without the intervention of a Jury. But this practice seems very questionable; wherever, by any constitution of Law, a man may enjoy the privilege of trial by Jury, great care should be taken that he be not deprived of it. To obviate these difficulties, it has been thought that a Commission might issue under 11 and 12 of William III. and the proceedings be regulated by the statute of 2S Henry VIII.

When this Court assembled but once in several years, its extraordinary jurisdiction was in some measure excused by the rare exercise of its powers; but when it meets so often as it has of late years in the West Indies, it affords a just ground of Legislative interference. Having treated of the several Courts, it will now be necessary to make a few observations upon the Laws of the country.

Laws of Nova Scotia

The Law of the Province is divisible into three parts. Is. the Common Law of England. 2d. the Statute Law of England. 3d. the Statute Law of Nova-Scotia. A minute consideration of each would be foreign from the design of this work, but the subject is too interesting to be altogether passed over. I shall therefore show in what manner the two first were introduced, the extent to which they apply, and the alteration made in them by the Local Statute Law.

Upon the first settlement of this country, as there was no established system of jurisprudence, until a local one was legally constituted, the emigrants naturally continued subject and entitled to the benefit of all such Laws of the parent country, as were applicable to their new situation. As their allegiance continued, and travelled along with them according to those Laws, their co-relative right of protection necessarily accompanied them.

The common law, composed of long established customs, originating beyond what is technically called the memory of man, gradually crept into use as occasion and necessity dictated. The Statute Law, consisting of acts, regularly made and enacted by constituted authority, has increased as the nation has become more refined, and its relationship more intricate. As both these laws grew up with the local circumstances of the times, so it cannot be supposed that either of them, in every respect, ought to be in force in a new settled country ; because crimes that are the occasion of penalties, especially those arising out of political, instead of natural and moral relationship, are not equally crimes in every situation.

Of the two, the common law is much more likely to apply to an infant colony, because it is coeval with the earliest periods of the English history, and is mainly grounded on general moral principles, which are very similar in every situation and in every country. The common law of England, including those statutes which are in affirmance of it, contains all the fundamental principles of the British constitution, and is calculated to secure the most essential rights and liberties of the subject. It has therefore been considered by the highest jurisdictions in the parent country, and by the legislatures of every colony, to be the prevailing law in all cases not expressly altered by statute, or by an old local usage of the colonists, similarly situated; for there is a colonial common Law, common to a number of colonies, as there is a customary common Law, common to all the Realm of England.

With such exceptions, not only the civil but the penal part of it, as well as the rules of administering justice and expounding Laws, have been considered as binding in Nova-Scotia. In many instances, to avoid question, colonial statutes and rules of court have been made, expressly adopting them. Since the artificial refinements and distinctions incidental to the property of the mother country, the laws of police and revenue, such especially as are enforced by penalty, the modes of maintenance for the clergy, the Jurisdiction of the spiritual Courts, and a multitude of other provisions, are neither necessary nor convenient for such a colony, and therefore are not in force here.

The rule laid down by Blackstone is, that all Acts of Parliament, made in affirmance or amendment of the common law, and such as expressly include the colonies by name, are obligatory in this country. On the first part of this proposition there can be no difficulty, except as to determining whether a particular statute is in fact in amendment and affirmance of the common law or not, and whether any particular act of Parliament is applicable or not to the state of the Colony. The power of making this decision, a power little short of legislation, is and must be left with the Judges of our Local Courts, and on referring to the manner in which it has been exercised, there is little danger to be apprehended that an improper use will be made of it. Hence it is that the rights of the subject, as declared in the petition of rights, the limitation of the prerogative by the act for abolishing the Star Chamber, and regulating the Privy Council, the Habaes Corpus act and the Bill of rights, extend to the Colonies. In the same manner do all statutes respecting the general relation between the crown and the subject, such as the Laws relative to the succession, to treason, &e. extend throughout the Realm.

—The difference between the local and general laws, or clauses of a law, may be illustrated by 13 and 14 of Charles II. c. 2. By that act the supreme military power is vested in the King without limitation ; this part of the act extends to all the Colonies, but the enacting clause respecting the militia officers applies to England alone. The other part of the proposition of Blackstone, that act; of Parliament are binding upon such Colonies as are expressly named therein, is not expressed with his usual accuracy, and must be understood with some very material exceptions. It is true that Parliament has declared, by act 6. Geo. III. c. 12, that it has the power to make laws and statutes of sufficient validity to bind the Colonies in all cases whatever. But it is plain, if it had not the power before, it is impossible the mere declaration could invest it with it.

I have already observed that the true line is, that Parliament is supreme in all external, and the Colonial Assemblies in all internal legislation ; and that the Colonies have a right to be governed, within their own jurisdiction, by their own laws, made by their own internal will. But if the Colonies exceed their peculiar limits, form other alliances, or refuse obediance to the general laws for the regulation of Commerce or external Government, in these cases there must necessarily be a coercive power lodged somewhere : and cannot be lodged more safely for the Empire at large than in Parliament, which has an undoubted right to exercise it in such cases of necessity. It is in this manner the passage alluded to, in the commentaries, must be understood, which states those laws to be binding on the Colonies that include them by express words, and the English act of Parliament is generally received in the same sense.

The system of jurisprudence is, from these circumstances, very similar in both countries; and as it is a fundamental principle in all the Colonies not to enact laws repugnant to those of England, the deviation is less than might be supposed. The statute of distribution has been already alluded to and explained, and it may be added that, as respects wills, the same formality in execution, and the same rules of construction, as prevail in the parent state, are adopted here. For other peculiarities the reader is referred to various parts of this work, where they are incidentally mentioned.”

Haliburton, Thomas Chandler. “An historical and statistical account of Nova-Scotia : in two volumes” Halifax [N.S.] : J. Howe, 1829. Volume I: https://archive.org/details/historicalstatis01hali/mode/2up, Volume II: https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-rbsc_lc_historical-nova-scotia_lande00400-v2-16708/mode/2up