An expanded version of what’s put forth by the Nova Scotia legislature.

1493 – May 4, Alexander VI, Pope of Rome, issued a bull, granting the New World. Spain laid claim to the entire North American Coast from Cape Florida to Cape Breton, as part of its territory of Bacalaos.

1496 – March 5, Henry VII, King of England issued a commission to John Cabot and his sons to search for an unknown land

1498 – March 5, Letters Patents of King Henry the Seventh Granted unto John Cabot and his Three Sonnes, Lewis, Sebastian and Sancius for the “Discouerie of New and Unknowen Lands”

1502 – Henry VII commissioned Hugh Eliot and Thomas Ashurst to discover and take possession of the islands and continents in America; “and in his name and for his use, as his vassals, to enter upon, doss, conquer, govern, and hold any Mainland or Islands by them discovered.”

1524 – Francis I, King of France, said that he should like to see the clause in Adam’s will, which made the American continent the exclusive possession of his brothers of Spain and Portugal, is said to have sent out Verrazzano, a Florentine corsair, who, as has generally been believed, explored the entire coast from 30° to 50° North Latitude, and named the whole region New France.

1534 – King Francis commissioned Jacques Cartier to discover and take possession of Canada; “his successive voyages, within the six years following, opened the whole region of St. Lawrence and laid the foundation of French dominion on this continent.”

1578 – June 11, Letters patent granted by Elizabeth, Queen of England to Sir Humphrey Gilbert, knight, for “the inhabiting and planting of our people in America”.

1584 – March 25, Queen Elizabeth renewed Gilbert’s grant to Sir Walter Raleigh, his half-brother. Under this commission, Raleigh made an unsuccessful attempt to plant an English colony in Virginia, a name afterwards extended to the whole North Coast of America in honor of the “Virgin” Queen.

1603 – November 8, Henry IV, King of France, granted Sieur de Monts a royal patent conferring the possession of and sovereignty of the country between latitudes 40° and 46° (from Philadelphia as far north as Katahdin and Montreal). Samuel Champlain, geographer to the King, accompanied De Monts on his voyage, landing at the site of Liverpool, N.S., a region already known as “Acadia.”

1606 – April 10, King James claimed the whole of North America between 34° and 45° North latitude, granting it to the Plymouth and London Companies. This entire territory was placed under the management of one council, the Royal Council for Virginia. The Northern Colony encompassed the area from 38° to 45° North latitude.

1620 – November 3, Reorganization of the Plymouth Company in 1620 as the Council of Plymouth for New England, encompassing from 40° to 48° North latitude.

1621 – September 29, Charter granted to Sir William Alexander for Nova Scotia

1625 – July 12, A grant of the soil, barony, and domains of Nova Scotia to Sir Wm. Alexander of Minstrie

1630 – April 30, Conveyance of Nova-Scotia (Port-royal excepted) by Sir William Alexander to Sir Claude St. Etienne Lord of la Tour and of Uarre and to his son Sir Charles de St. Etienne Lord of St. Denniscourt, on condition that they continue subjects to the king of Scotland under the great seal of Scotland.

1632 – March 29, Treaty between King Louis XIII. and Charles King of England for the restitution of the New France, Cadia and Canada and ships and goods taken from both sides. Made in Saint Germain

1638 – Grant to Charnesay and La Tour

1654 – August 16, Capitulation of Port-Royal

1656 – August 9, A grant by Cromwell to Sir Charles de Saint Etienne, a baron of Scotland, Crowne and Temple

1667 – July 31, The treaty of peace and alliance between England and the United Provinces made at Breda

1668 – February 17, Act of cession of Acadia to the King of France

1689 – English Bill of Rights enacted

1691, October 7, A charter granted by king William and Queen Mary to the inhabitants of the province of Massachusetts Bay, in New England

1713 – March 31, Treaty of peace and friendship between Louis XIV. King of France, and Anne, Queen of Great Britain, made in Utrecht

1713 – April 11, Treaty of navigation and commerce between Louis XIV, king of France, and Anne, Queen of Great Britain

1719 – June 19, Commission to Richard Philips to be Governor (including a copy of the 1715 Instructions given to the Governor of Virginia, by which he was to conduct himself)

1725 – August 26, Explanatory Charter of Massachusetts Bay

1725 – December 15, A treaty with the Indians (Peace and Friendship Treaty, ratification at Annapolis)

1727 – July 25, Ratification at Casco Bay of the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1725

1728 – May 13, Ratification at Annapolis Royal of the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1725

1748, October 7–18, The general and definitive treaty of peace concluded at Aix-la-Chapelle

1749 – September 4, Renewal of the Peace and Friendship treaty of 1725

1752 – November 22, Treaty between Thomas Hopson, Governor in Chief in and over His Majesty’s Province of Nova Scotia and Major Jean Baptiste Cope, Chief Sachem of the Tribe of the MickMack Indians inhabiting the Eastern Coast…

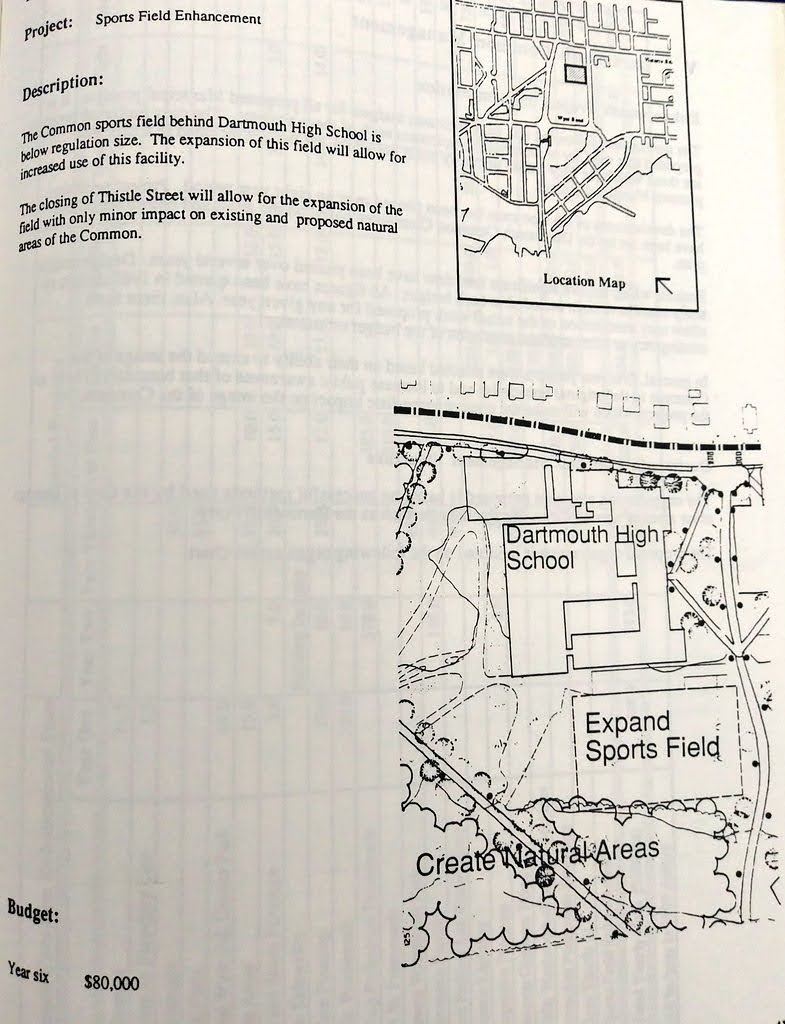

1758 – Nova Scotia Legislature established (consisting of the Lieutenant Governor, his Council and the newly established, elected legislative assembly called the House of Assembly)

1760 – March, Treaty of Peace and Friendship concluded by the Governor of Nova Scotia with Paul Laurent, Chief of the La Heve tribe of Indians

1761 – November 9, Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Jonathon Belcher and Francis Muis

1763 – February 10, France ceded, for the last time, the rest of Acadia, including Cape Breton Island (‘île Royale), the future New Brunswick and St John’s Island (later re-named Prince Edward Island), to British (Treaty of Paris) and it was joined to Nova Scotia

1763 – October 7, Royal Proclamation

1769 – Prince Edward Island established as a colony separate from Nova Scotia

1779 – September 22, Treaty signed at Windsor between John Julien, Chief and Michael Francklin, representing the Government of Nova Scotia

1784 – Cape Breton Island and New Brunswick established as colonies separate from Nova Scotia

1820 – Cape Breton Island re-joined to Nova Scotia

1838 – Separate Executive Council and Legislative Council established

1848 – Responsible government established in Nova Scotia (Members of the legislature had the ability to elect a majority of those in the Legislative council)

1867 – “Union” of provinces of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as the “self-governing” federal colony of the Dominion of Canada (British North America Act, 1867 — now known in Canada as Constitution Act, 1867) & the Parliament of Canada established (consisting of the Queen, the Senate and the House of Commons)

1928 – Abolition of the Legislative Council (leaving the Legislature consisting of the Lieutenant Governor and the House of Assembly)

1931 – Canadian independence legally recognized (Statute of Westminster, 1931)

1960 – Canadian Bill of Rights enacted

1982 – patriation of the amendment of the Constitution of Canada & adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982, including the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Canada Act 1982)

Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia. J. Stockdale, 1787. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/gdc/lhbcb/04902/04902.pdf

Legislature of the State of Maine. “The Revised Statutes of the State of Maine, Passed August 29, 1883, and Taking Effect January 1,1884.”, Portland, Loring, Short & Harmon and William M. Marks. 1884. https://lldc.mainelegislature.org/Open/RS/RS1883/RS1883_f0005-0017_Land_Titles.pdf

Kennedy, William P. Statutes, Treaties and Documents of the Canadian Constitution: 1713-1929. Oxford Univ. Pr., 1930. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_03428

Harvard Law School Library. “Description Legislative history regarding treaties of commerce with France, Spain relating to New Foundland, Nova Scotia, and Cape Breton,” ca. 1715? Small Manuscript Collection, Harvard Law School Library. https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HLS.LIBR:19686447, Accessed 07 June 2021

Thorpe, Francis Newton. “The Federal and State constitutions: colonial charters, and other organic laws of the States, territories, and Colonies, now or heretofore forming the United States of America” Washington : Govt. Print. Off. 1909. https://archive.org/details/federalstatecons07thor/page/n5/mode/2up

Murdoch, Beamish. “Epitome of the laws of Nova-Scotia” [Halifax, N.S.? : s.n.], 1832 (Halifax, N.S. : J. Howe) Volume One: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.59437, Volume Two: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.59438, Volume Three: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.59439, Volume Four: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.59440

Marshall, John G. “The justice of the peace, and county and township officer in the province of Nova Scotia : being a guide to such justice and officers in the discharge of their official duties” [Halifax, N.S.? : s.n.], 1837 (Halifax [N.S.] : Gossip & Coade) https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.36869, Second Edition: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.38224

Livingston, Walter Ross. Responsible Government In Nova Scotia: a Study of the Constitutional Beginnings of the British Commonwealth. Iowa City: The University, 1930. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89080043730, https://archive.org/details/responsiblegover0000livi

Bourinot, John George. “The constitution of the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia” [S.l. : s.n., 1896?] https://archive.org/details/cihm_10453/page/141, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.10453/14?r=0&s=1

Laing, David, editor. “Royal letters, charters, and tracts, relating to the colonization of New Scotland, and the institution of the Order of knight baronets of Nova Scotia. -1638“. [Edinburgh Printed by G. Robb, 1867] https://archive.org/details/royallettersc11400lainuoft

Labaree, Leonard Woods. “Royal Instructions to British Colonial Governors 1670–1776“. Vol. I and Vol. II. The American Historical Association. (New York : D. Appleton-Century Company, 1935) https://archive.org/details/royalinstruction0001laba, https://archive.org/details/royalinstruction0002laba

Beamish Murdoch, “On the origin and sources of the Law of Nova Scotia” (An essay on the Origin and Sources of the Law of Nova Scotia read before the Law Students Society, Halifax, N.S., 29 August 1863), (1984) 8:3 DLJ 197. https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1399&context=dlj

Shirley B. Elliott, “An Historical Review of Nova Scotia Legal Literature: a select bibliography”, Comment, (1984) 8:3 DLJ 197. https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/dlj/vol8/iss3/12/