“The [Mi’kmaq] had appeared in the neighborhood of the town for several weeks, but intelligence had been received that they had commenced hostilities, by the capture of twenty persons at Canso… On the last day of September they made an attack on the sawmill at Dartmouth, then under the charge of Major Gilman. Six of his men had been sent out to cut wood without arms. The [Mi’kmaq] laid in ambush, killed four and carried off one, and the other escaped and gave the alarm, and a detachment of rangers was sent after the [Mi’kmaq], who having overtaken them, cut off the heads of two [Mi’kmaq] and scalped one.

This affair is mentioned in a letter from a gentleman in Halifax to Boston, dated October 2nd as follows: “About seven o’clock on Saturday morning before, as several of Major Gilman’s workmen with one soldier, unarmed, were hewing sticks of timber about 200 yards from his house and mills on the east side of the harbor, they were surprised by about 40 [Mi’kmaq], who first fired two shots and then a volley upon them which killed four, two of whom they scalped, and cut off the heads of the others, the fifth is missing and is supposed to have been carried off.”

“The Governor deeming it expedient that some permanent system of judicial proceedings to answer the immediate exigencies of the Colony should be established, a committee of Council was accordingly appointed to examine the various systems in force in the old Colonies. On 13th December, Mr. Green reported that after a careful investigation, the laws of Virginia were found to be most applicable to the present situation of the province. The report was adopted. It referred principally to the judicial proceedings in the General Courts, the County Courts, and other tribunals.”

[More on the constitutional connections between Nova Scotia and Virginia: Virginia and Nova Scotia: An Historical Note, “As Near as May Be Agreeable to the Laws of this Kingdom”: Legal Birthright and Legal Baggage at Chebucto, 1749, Draught of H.M. Commission to Richard Philips to be Governor of Placentia and Cap. General and Governor in Chief of Nova Scotia or Accadie, June 19 1719 (relying on) Commission and Instructions to the Earl of Orkney for the Government of Virginia, 1715, Catalogue of books in the Nova Scotia Legislative Council Library, The First Charter of Virginia (1606)]

“In the month of August, 1750, three hundred and fifty-three settlers arrived in the ship Alderney… Those who came in the ship Alderney, were sent to the opposite side of the harbor, and commenced the town of Dartmouth, which was laid out in the autumn of that year. In December following, the first ferry was established, and John Connor appointed ferryman by order in Council.

In the Spring of the following year the [Mi’kmaq] surprised Dartmouth at night, scalped a number of settlers and carried oft several prisoners. The inhabitants, fearing an attack, had cut down the spruce trees around their settlement, which, instead of a protection, as was intended, served as a cover for the enemy. Captain Clapham and his company of Rangers were stationed on Block-house hill, and it is said remained within his block-house firing from the loop-holes, during the whole affair. The [Mi’kmaq] were said to have destroyed several dwellings, sparing neither women nor children. The light of the torches and the discharge of musketry alarmed the inhabitants of Halifax, some of whom put off to their assistance, but did not arrive in any force till after the [Mi’kmaq] had retired. The night was calm, and the cries of the settlers, and whoop of the [Mi’kmaq] were distinctly heard on the western side of the harbor. On the following morning, several bodies were brought over — the [Mi’kmaq] having carried off the scalps. Mr. Pyke, father of the late John George Pyke, Esq., many years police magistrate of Halifax, lost his life on this occasion. Those who fled to the woods were all taken prisoners but one. A court martial was called on the 14th May, to inquire into the conduct of the different commanding officers, both commissioned and non-commissioned, in permitting the village to be plundered when there were about 60 men posted there for its protection.

There was a guard house and small military post at Dartmouth from the first settlement, and a gun mounted on the point near the Saw Mill (in the cove) in 1749. One or two transports, which had been housed over during winter and store ships were anchored in the cove, under cover of this gun, and the ice kept broke around them to prevent the approach of the [Mi’kmaq]. The attempt to plant a settlement at Dartmouth, does not appear to have been at first very successful. Governor Hobson in his letter to the Board of Trade, dated 1st October, 1753, says, “At Dartmouth there is a small town well picketed in, and a detachment of troops to protect it, but there are not above five families residing in it, as there is no trade or fishing to maintain any inhabitants, and they apprehend danger from the [Mi’kmaq] in cultivating any land on the outer side of the pickets.”

There is no record of any concerted attack having been made by the [Mi’kmaq] or French on the town of Halifax.”

“German palatine settlers (arrived on the 10th of June 1751, and) they were employed at Dartmouth in picketing in the back of the town.”

“On February 3rd 1752, a public ferry was established between Halifax and Dartmouth and John Connors appointed ferryman for three years, with the exclusive privilege, and ferry regulations were also established.”

“The government mills at Dartmouth, under charge of Captain Clapham, were sold at auction in June. They were purchased by Major Gilman for $310.”

“In 1754, an order was made for permission to John Connors, to assign the Dartmouth Ferry to Henry Wynne and William Manthorne.”

January 26th 1756, the term of Henry Wynne and William Manthorne’s licenses of the Dartmouth and Halifax ferry having expired, John Rock petitioned and obtained the same on the terms of his predecessors.”

“(1757) was also memorable as the one in which Representative government was established in Nova Scotia. The subject of calling a Legislative Assembly had undergone much discussion. It had been represented by the Governor and Council, to the authorities in England, that such a step at that particular time would be fraught with much danger to the peace of the colony. Chief Justice Belcher, however, having given his opinion that the Governor and Council possessed no authority to levy taxes, and their opinion being confirmed in England, it was resolved by council on January 3rd 1757, that a representative system should be established and that twelve members should be elected by the province at large, until it could be conveniently divided into counties, and that the township of Halifax should send four members, Lunenburg two, Dartmouth one, Lawrencetown one, Annapolis Royal one, and Cumberland one, making in all twenty-two members, and the necessary regulations were also made for carrying into effect the object intended.”

“In September, 1785, a number of whalers from Nantucket came to Halifax ; three brigantines and one schooner, with crews and everything necessary for prosecuting the whale fishery, which they proposed to do under the British flag. Their families were to follow. A short time after they were joined by three brigantines and a sloop from the same place. On the twentieth of October following, the Chief Land Surveyor was directed to make return of such lands as were vacant at Dartmouth to be granted to Samuel Starbuck, Timothy Folger, and others, from Nantucket, to make settlement for the whalers. The Town of Dartmouth had been many years previously laid out in lots which had been granted or appropriated to individuals, some of whom had built houses, and others though then vacant, had been held and sold from time to time by their respective owners. Most of these lots were reported vacant by Mr. Morris, the surveyor, and seized upon by the Government, as it is said, without any proceeding of escheat, and re-granted to the Quakers from Nantucket, which caused much discontent, and questions of title arose and remained open for many years after.”

“The whale fishery was the chief subject which engaged the attention of the public during (1785). Much advantage was expected to accrue to the commerce of the place from the Quakers from Nantucket having undertaken to settle in Dartmouth. They went on prosperously for a short time, until they found the commercial regulations established in England for the Colonies were hostile to their interests, and they eventually removed, some of them, it is said, to Wales and other parts of Great Britain, where they carried on their fishery to more advantage.

A petition was presented this autumn to the Governor and Council from a number of merchants, tradesmen and other inhabitants, praying for a Charter of Incorporation for the Town of Halifax. This was the first occasion on which the subject was brought prominently before the public. It was, however, not deemed by the government ” expedient or necessary ” to comply with the prayer of the petition. The reasons are not given in the Minute of Council, which bears date 17th November, 1785. The names of the Councillors present were Richard Bulkeley, Henry Newton, Jonathan Binney, Arthur Goold, Alexander Brymer, Thomas Cochran and Charles Morris.

The functions of His Majesty’s Council at this period of our history embraced all departments of executive authority in the Colony. They were equally supreme in the control of town affairs as those of the province at large. The magistrates, though nominally the executive of the town, never acted in any matter of moment without consulting the Governor and Council. The existence of a corporate body having the sole control of town affairs would in a great measure deprive them of that supervision which they no doubt deemed, for the interest of the community, should remain in the Governor and Council.”

“Folger and Starbuck, the Quaker whalers, who settled at Dartmouth a year or two since, left (in 1792), for Milford Haven in Great Britain, where they expected to carry on their whale fishery with greater facilities than at Dartmouth.”

“…the Governor, M. Danseville, with several hundred prisoners and stores were brought to Halifax. They landed on the 20th of June (1793). Governor Danseville was placed on parole, and resided at Dartmouth for many years in the house known as Brook House, now or lately the residence of the Hon. Michael Tobin, Jr., about a couple of miles or more from Dartmouth town. The old gentleman displayed some taste in beautifying the grounds at Brook House. He built a fish pond and laid out walks among the beech and white birch groves near the house. The pond still remains, but the walks and most of the trees have long since disappeared. He remained a prisoner with an allowance from Government until the peace of 1814, when he returned to his own country a zealous royalist.”

“a poll tax had been imposed by Act of Legislature in 1791.”

“During the spring of 1796 Halifax suffered from a scarcity of provisions. The inhabitants were indebted to Messrs. Hartshorne and Tremain, whose mills at Dartmouth enabled them, through the summer, to obtain flour at a reduced price and to afford a sufficient supply for the fishery.”

“The following list of town officers appointed by the Grand Jury for the Town March 5th 1806, will be found interesting: … Edward Foster, Surveyor of highways from Dartmouth Town Plot to the Basin; Samuel Hamilton, Constable from Dartmouth Town Plot to the Basin; Jon. Tremain, Sr., William Penny, Surveyors of Highways, Dartmouth Town Plot; David Larnard, Constable, Dartmouth Town Plot; James Munn, Pound Keeper, Dartmouth Town Plot; Henry Wisdom, Surveyor of Highways from the Ferry up the Preston Road to Tanyard”

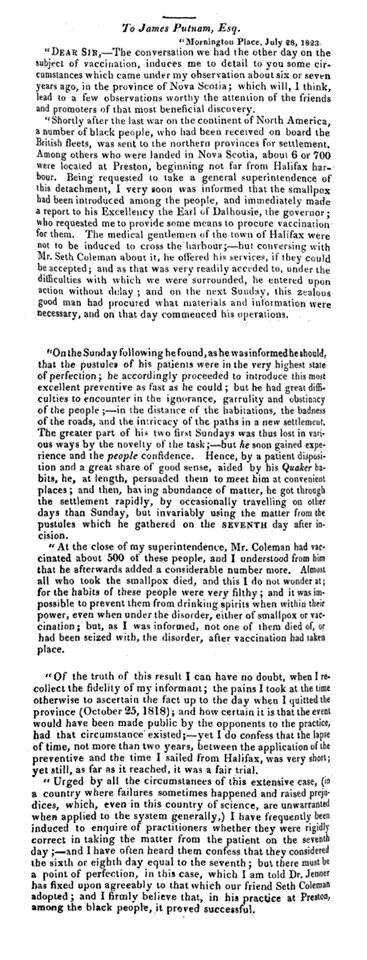

“In the autumn (of 1814) the small pox made its appearance in Dartmouth and Preston and was very fatal among the Chesapeake blacks].”

“There were two ferries (in 1815). The upper ferry was conducted by John Skerry, whose memory is still cherished by many, both in Dartmouth and Halifax, as one of the most obliging and civil men of his day. Skerry’s wharf in Dartmouth was a short distance south of the steam boat wharf (—at the foot of Ochterloney Street today). The other ferry was the property of Mr. James Creighton, known as the Lower Ferry, situate to the south of Mott’s Factory (—at the bottom of Old Ferry Road). It was conducted for Mr. Creighton by deputy and was afterwards held under lease by Joseph Findlay, the last man who ran a ferry boat with sails and oars in Halifax Harbor. These ferry boats were furnished with a lug sail and two and sometimes four oars. They were large clumsy boats and occupied some thirty or forty minutes in making the passage across the harbor. There were no regular trips at appointed hours. When the boat arrived at either side the ferryman blew his horn (a conch shell) and would not start again until he had a full freight of passengers. The sound of the conch and the cry of ”Over! Over! ” was the signal to go on board. The boats for both ferries landed at the Market Slip at Halifax.

An act of the Legislature had been obtained this session to incorporate a Steamboat Company with an exclusive privilege of the ferry between Halifax and Dartmouth for 25 years. They could not succeed in getting up a company, steam navigation being then in its infancy, and in the following year had the act amended to permit them to run a boat by horses to be called the Team-boat. This boat consisted of two boats or hulls united by a platform with a paddle between the boats. The deck was surmounted by a round house which contained a large cogwheel, arranged horizontally inside the round house, to which were attached 8 or 9 horses harnessed to iron stanchions coming down from the wheel. As the horses moved round, the wheel turned a crank which moved the paddle. It required about twenty minutes for this boat to reach Dartmouth from Halifax. It was considered an immense improvement on the old ferry boat arrangement, and the additional accommodation for cattle, carriages and horses was a great boon to the country people as well as to the citizens of Halifax, who heretofore had been compelled to employ Skerry’s scow when it was found necessary to carry cattle or carriages from one side of the harbor to the other.

The first trip of the Team-boat was made on the 8th November, 1810. The following year an outrage was committed which caused much excitement and feeling in the town. All the eight horses in the boat were stabbed by a young man named Hurst. No motive for this cruel act could be assigned, drunkenness alone appearing to be the cause. The culprit was tried for the offence and suffered a lengthy imprisonment. Mr. Skerry kept up a contest with the Company for several years, until all differences were arranged by his becoming united with the Company, and after a short time old age and a small fortune, accumulated by honest industry, removed him from the scene of his labors.

The team-boat after a year or two received an addition to her speed by the erection of a mast in the centre of the round house, on which was hoisted a square sail when the wind was fair, and afterwards a topsail above, which gave her a most picturesque appearance on the water. This addition considerably facilitated her motion and relieved the horses from their hard labor. As traffic increased several small paddle boats were added by the Company, which received the appellation of Grinders. They had paddles at the sides like a steamboat, which were moved by a crank turned by two men. In 1818 the proprietors of the old ferries petitioned the House of Assembly against the Teamboat Company suing these small boats as contrary to the privilege given them by the Act of Incorporation. It afterwards became a subject of litigation until the question was put an end to by Mr. Skerry becoming connected with the Company. Jos. Findlay continued to run his old boats from the south or lower ferry until about the year 1835.”

“During the month of February (1818), the harbor was blocked up with float ice as far down as George’s Island. Between 13th and 20th, persons crossed from Dartmouth on the ice at the Narrows.”

“By the 27th of January 1821 the ice formed a firm bridge between Halifax and Dartmouth, over which a continuous line of sleighs, teams and foot passengers might be seen on market days.”

Akins, Thomas B., 1809-1891. History of Halifax City. [Halifax, N.S.?: s.n.], 1895. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/aeu.ark:/13960/t7zk65s8s