“The [Mi’kmaq], first called by the French Souriqu’ois, held possession of Nova Scotia and the adjacent isles, and were early known as the active allies of the French.

Marquis de la Roche

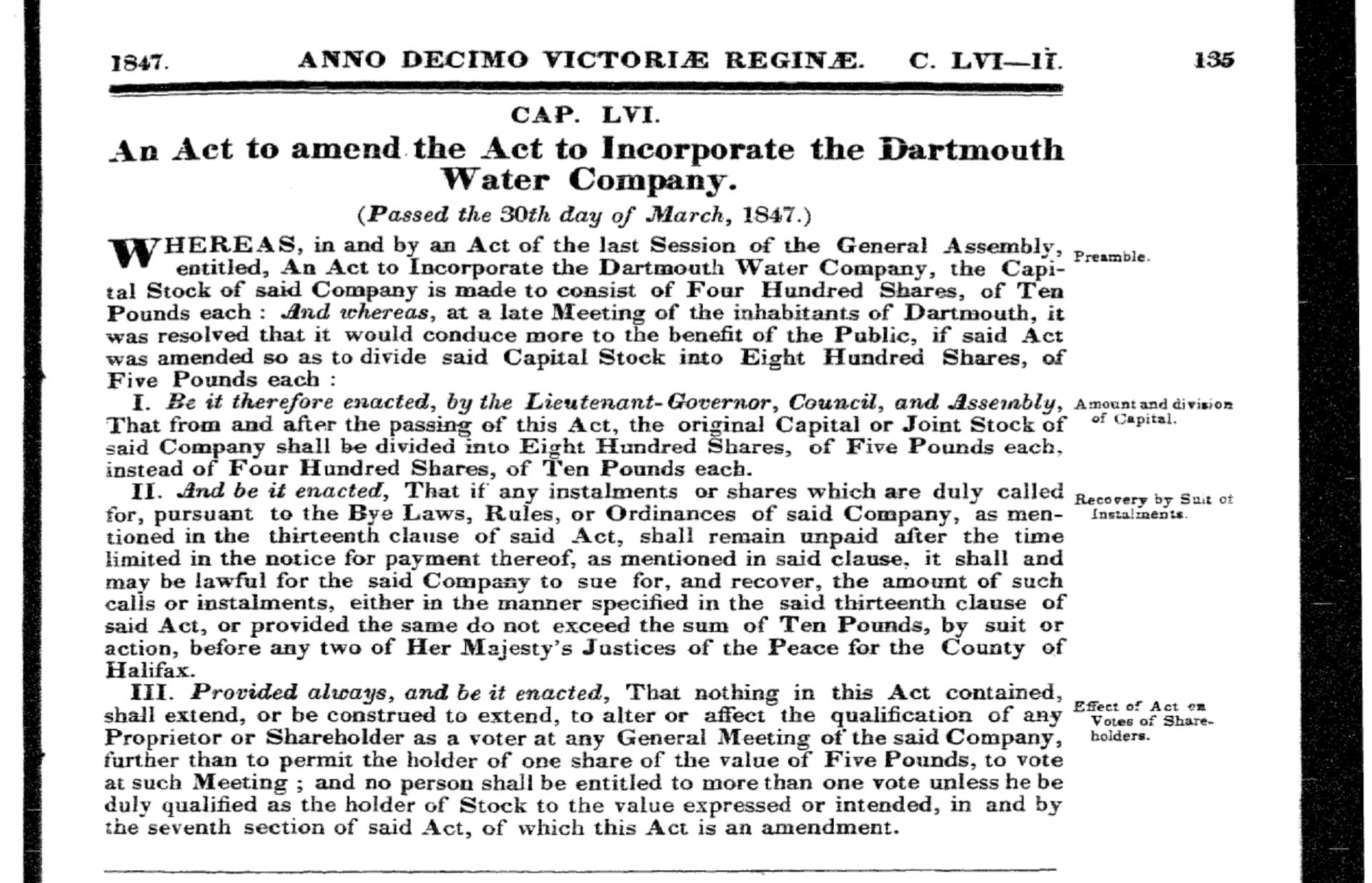

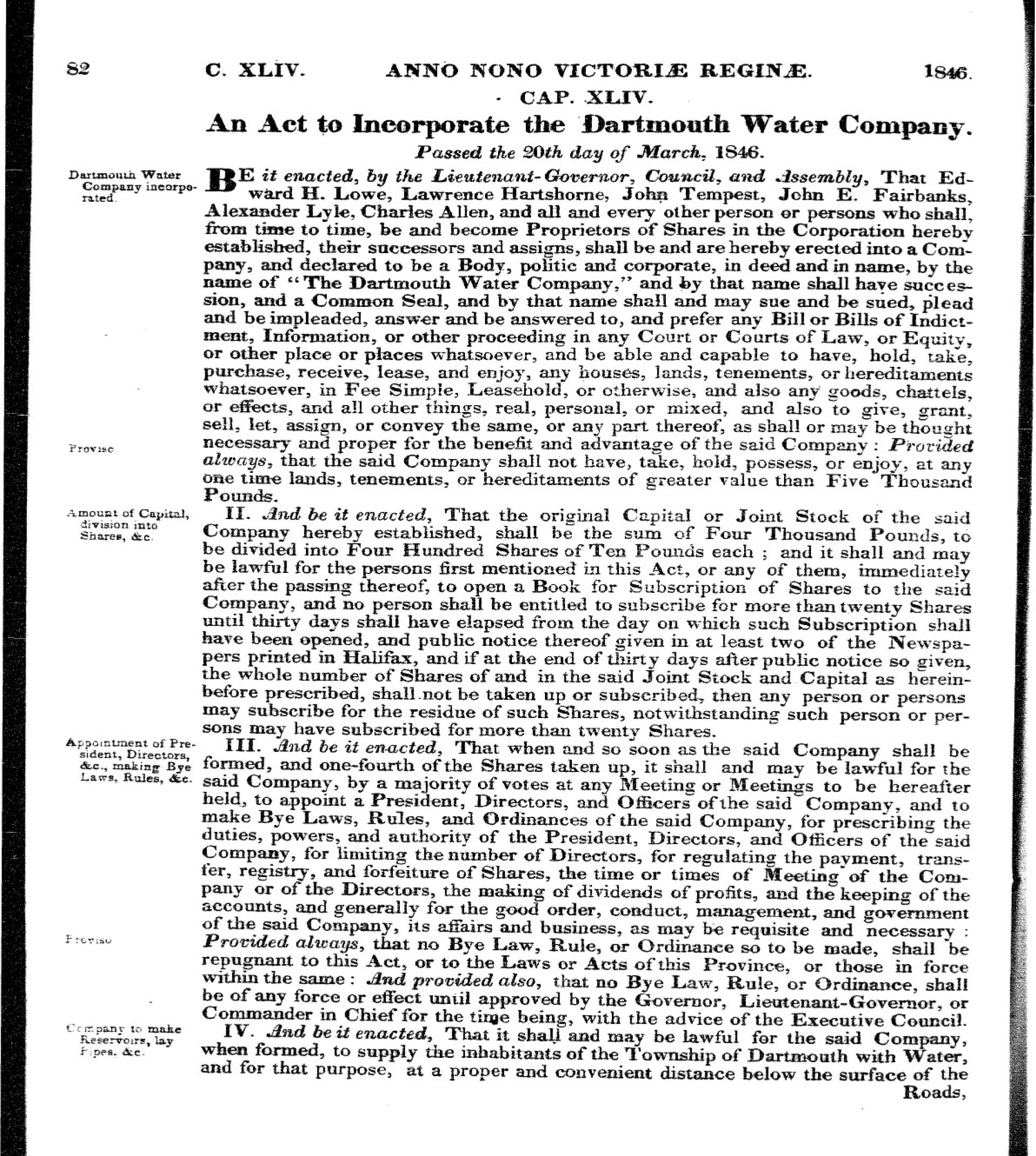

In 1598, the Marquis de la Roche, a French nobleman, received from the King of France a commission for founding a French colony in America. Having equipped several vessels, he sailed with a considerable number of settlers, most of whom, however, he was obliged to draw from the prisons of Paris. On Sable island, a barren spot near the coast of Nova Scotia, forty men were left to form a settlement.

La Roche dying soon after his return, the colonists Fate were neglected; and when, after seven years, a vessel was sent to inquire after them, only twelve of them were living. The dungeons from which they had been liberated were preferable to the hardships which they had suffered. The emaciated exiles were carried back to France, where they were kindly received by the king, who pardoned their crimes, and made them a liberal donation.

De Monts

In 1603, the king of France granted to De Monts, a gentleman of distinction, the sovereignty of the country from the 40th to the 46th degree of north latitude; that is, from one degree south of New York city, to one north of Montreal. Sailing with two vessels, in the spring of 1604, he arrived at Nova Scotia in May, and spent the summer in trafficking with the natives, and examining the coasts preparatory to a settlement.

Selecting an island near the mouth of the river St. Croix, on the coast of New Brunswick, he there erected a fort and passed a rigorous winter, his men suffering much from the want of suitable provisions. ‘In the following spring, 1605, De Monts removed to a place on the Bay of Fundy; and here was formed the first permanent French settlement in America. The settlement was named Port Royal, and the whole country, embracing the present New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the adjacent islands, was called Acadia.

North and South Virginia

In 1606 James the 1st, of England, claiming all that portion of North America which lies between the 34th and the 45th degrees of north latitude, embracing the country from Cape Fear to Halifax, divided this territory into two nearly equal districts; the one, called North Virginia, extending from the 41st to the 45th degree; and the other, called South Virginia, from the 34th to the 38th.

The former he granted to a company of “Knights, gentlemen, and merchants,” of the west of England, called the Plymouth Company; and the latter to a company of “noblemen, gentlemen, and merchants,” mostly resident in London, and called the London Company. The intermediate district, from the 38th to the 41st degree, was open to both companies; but neither was to form a settlement within one hundred miles of the other.

…Early in the following year, 1690, Schenectady was burned; the settlement at Salmon Falls, on the Piscataqua, was destroyed; and a successful attack was made on the fort and settlement at Casco Bay. In anticipation of the inroads of the French, Massachusetts had hastily fitted out an expedition, under Sir William Phipps, against Nova Scotia, which resulted in the easy conquest of Port Royal.

Early in 1692 Sir William Phipps returned with a new charter, which vested the appointment of governor in the king, and united Plymouth, Massachusetts, Maine, and Nova Scotia, in one royal government. Plymouth lost her separate government contrary to her wishes; while New Hampshire, which had recently placed herself under the protection of Massachusetts, was now forcibly severed from her.

In 1707 Massachusetts attempted the reduction of Port Royal; and a fleet conveying one thousand soldiers was sent against the place; but the assailants were twice obliged to raise the siege with considerable loss. Not disheartened by the repulse, Massachusetts spent two years more in preparation, and aided by a fleet from England, in 1710 again demanded the surrender of Port Royal. The garrison, weak and dispirited, capitulated after a brief resistance; the name of the place was changed to Annapolis, in honor of Queen Anne; and Acadia, or Nova Scotia, was permanently annexed to the British crown.

The most important event of (King George’s War) in America, was the siege and capture of Louisburg. This place, situated on the island of Cape Breton, had been fortified by France at great expense, and was regarded by her as the key to her American possessions, William Shirley the governor of Massachusetts, perceiving the importance of the place, and the danger to which its possession by the French subjected the British province of Nova Scotia, laid before the legislature of the colony a plan for its capture. Although Strong objections wore urged, the govenor’s proposals were assented to; Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire, furnished their quotas of men; New York sent a supply of artillery, and Pennsylvania of provisions. Commodore Warren, then in the West Indies with an English fleet, was invited to co-operate in the enterprise, but he declined doing so without orders from England. This unexpected intelligence was kept a secret, and in April, 1745, the New England forces alone, under William Pepperell, commander-in-chief, and Roger Wolcott, second in command, sailed for Louisburg.

At Causcau they were unexpectedly met by the fleet of Commodore Warren, who had recently received orders to repair to Boston, and concert measures with Governor Shirley for his majesty’s service in North America. On the 11th of May the combined forces, numbering more than 4000 land troops, came in sight of Louisburg, and effected a landing at Gabarus Bay, which was the first intimation the French had of their danger. On the day after the landing a detachment of four hundred men marched by the city and approached the royal battery, setting fire to the houses and stores on the way. The French, imagining that the whole army was coming upon them, spiked the guns and abandoned the battery, which was immediately seized by the New England troops. Its guns were then turned upon the town, and against the island battery at the entrance of the harbor.

As it was necessary to transport the guns over a morass, where oxen and horses could not be used, they were placed on sledges constructed for the purpose, and the men with ropes, sinking to their knees in the mud, drew them safely over. Trenches were then thrown up within two hundred yards of the city,—a battery was erected on the opposite side of the harbor, at the Light House Point and the fleet of Warren captured a French gunship, with five hundred and sixty men, and a great quantity of military stores designed for the supply of the garrison. A combined attack by sea and land was planned for the 29th of June, but, on the day previous, the city, fort, and batteries, and the whole island, were surrendered. This was the most important acquisition which England made during the war, and, for its recovery, and the desolation of the English colonies, a powerful naval armament under the Duke d’Anville was sent out by France in the following year. But storms, shipwrecks, and disease, enfeebled the fleet, and blasted the hopes of the enemy.

In 1748 the war was terminated by the treaty of Aix la Chapelle. The result proved that neither party had gained any thing by the contest; for all acquisitions made by either were mutually restored. But the causes of a future and more important war still remained in the disputes about boundaries, which were left unsettled; and the “French and Indian War” soon followed, which was the last struggle of the French for dominion in America.

Expeditions of Monckton, Braddock, Shirley, and Sir William Johnson.

Early in 1755, General Braddock arrived from Ireland, with two regiments of British troops, and with the authority of commander-in-chief of the British and colonial forces. At a convention of the colonial governors, assembled at his request in Virginia, three expeditions were resolved upon; one against the French at Fort du Quesne, to be led by General Braddock himself; a second against Niagara, and a third against Crown Point, a French post on the western shore of Lake Champlain.

While preparations were making for these expeditions, an enterprise, that had been previously determined undertaken. upon, was prosecuted with success in another quarter. About the last of May, Colonel Monckton sailed from Boston, with three thousand troops, against the French settlements at the head of the Bay of Fundy, which were considered as encroachments upon the English province of Nova Scotia. Landing at Fort Lawrence, on the eastern shore of Chignecto, a branch of the Bay of Fundy, a French block-house was carried by assault, and Fort Beausejour surrendered, after an investment of four days. The name of the fort was then changed to Cumberland. Fort Gaspereau, on Bay Verte, or Green Bay, was next taken; and the forts on the New Brunswick coast were abandoned. In accordance with the views of the governor of Nova Scotia, the plantations of the French settlers were laid waste; and several thousands of the hapless fugitives, ardently attached to their mother country, and refusing to take the oath of allegiance to Great Britain, were driven on board the British shipping, at the point of the bayonet, and dispersed, in poverty, through the English colonies.

Nova Scotia, according to its present limits, forms a large peninsula, separated from the continent by the Bay of Fundy, and its branch Chignecto, and connected with it by a narrow isthmus between the latter bay and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The peninsula is about 385 miles in length from northeast to southwest, and contains an area of nearly sixteen thousand square miles. The surface of the country is broken, and the Atlantic coast is generally barren, but some portions of the interior are fertile.

The settlement of Port Royal, (now Annapolis) by De Monts, in 1605, and also the conquest of the country by Argall, in 1614, have already been mentioned. France made no complaint of Argall’s aggression, beyond demanding the restoration of the prisoners, nor did Britain take any immediate measures for retaining her conquests. But in 1621 Sir William Alexander, afterwards Earl of Stirling, obtained from the king, James I, a grant of Nova Scotia and the adjacent islands, and in 1625 the patent was renewed by Charles I., and extended so as to embrace all Canada, and the northern portions of the United States. In 1623 a vessel was despatched with settlers, but they found the whole country in the possession of the French, and were obliged to return to England without effecting a settlement.

In 1628, during a war with France, Sir David Kirk, who had been sent out by Alexander, succeeded in reducing Nova Scotia, and in the following year he completed the conquest of Canada, but the whole country was restored by treaty in 1632.

The French court now divided Nova Scotia among three individuals, La Tour, Denys, and Razillai, and appointed Razillai commander-in-chief of the country. The latter was succeeded by Charnise, between whom and La Tour a deadly feud arose, and violent hostilities were for some time carried on between the rivals. At length, Charnise dying, the controversy was for a time settled by La Tour’s marrying the widow of his deadly enemy, but soon after La Borgne appeared, a creditor of Charnise, and with an armed force endeavored to crush at once Denys and La Tour. But after having subdued several important places, and while preparing to attack St. John, a more formidable competitor presented himself.

Cromwell, having assumed the reins of power in England, declared war against France, and, in 1654, despatched an expedition against Nova Scotia, which soon succeeded in reducing the rival parties, and the whole country submitted to his authority. La Tour, accommodating himself to circumstances, and making his submission to the English, obtained, in conjunction with Sir Thomas Temple, a grant of the greater part of the country. Sir Thomas bought up the share of La Tour, spent nearly 30,000 dollars in fortifications, and greatly improved the commerce of the country; but all his prospects were blasted by the treaty of Breda in 1667, by which Nova Scotia was again ceded to France

The French now resumed possession of the colony, which as yet contained only a few unpromising settlements, the whole population in 1680 not exceeding nine hundred individuals. The fisheries, the only productive branch of business, were carried on by the English. There were but few forts, and these so weak that two of them were taken and plundered by a small piratical vessel. In this situation, after the breaking out of the war with France in 1689, Acadia appeared an easy conquest. The achievement was assigned to Massachusetts, In May, 1690, Sir William Phipps, with 700 men, appeared before Port Royal, which soon surrendered; but he merely dismantled the fortress, and then left the country a prey to pirates. A French commander arriving in November of the following year, the country was reconquered, simply by pulling down the English and hoisting the French flag.

Soon after, the Bostonians, aroused by the depredations of the French and [indigenous] on the frontiers, sent a body of 500 men, who soon regained the whole country, with the exception of one fort on the river St. John. Acadia now remained in possession of the English until the treaty of Ryswick in 1697, when it was again restored to France.

It was again resolved to reduce Nova Scotia, and the achievement was again left to Massachusetts, with the assurance that what should be gained by arms would not again be sacrificed by treaty.

The peace of 1697 was speedily succeeded by a declaration of war against France and Spain in 1702. It was again resolved to reduce Nova Scotia, and the achievement was again left to Massachusetts, with the assurance that what should be gained by arms would not again be sacrificed by treaty. The first expedition, despatched in 1704, met with little resistance, but did little more than ravage the country. In 1707 a force of 1000 soldiers was sent against Port-Royal, but the French commandant conducted the defence of the place with so much ability, that the assailants were obliged to retire with considerable loss. In 1710 a much larger force, under the command of General Nicholson, appeared before Port Royal, but the French commandant, having but a feeble garrison, and declining to attempt a resistance, obtained an honorable capitulation. Port Royal was now named Annapolis. From this period Nova Scotia has been permanently annexed to the British crown.

The [Mi’kmaq] of Nova Scotia, who were warmly attached to the French, were greatly astonished on being informed that they had become the subjects of Great Britain. Determined, however, on preserving their independence, they carried on a long and vigorous war against the English. In 1720 they plundered a large establishment at Canseau, carrying off fish and merchandise to the amount of 10,000 dollars; and in 1723 they captured at the same place, seventeen sail of vessels, with numerous prisoners, nine of whom they deliberately and cruelly put to death.

As the [Mi’kmaq] still continued hostile, the British inhabitants of Nova Scotia were obliged to solicit aid from Massachusetts, and in 1728 that province sent a body of troops against the principal village of the Norridgewocks, on the Kennebec. ‘The enemy were surprised, and defeated with great slaughter, and among the slain was Father Ralle, their missionary, a man of considerable literary attainments, who had resided among the [Mi’kmaq] forty years. By this severe stroke the [Mi’kmaq] were overawed, and for many years did not again disturb the tranquility of the English settlements.

In 1744 war broke out anew between England and France. The French governor of Cape Breton immediately attempted the reduction of Nova Scotia, took Canseau, and twice laid siege to Annapolis, but without effect. The English, on the other hand, succeeded in capturing Louisburg, the Gibraltar of America, but when peace was concluded, by the treaty of Aix la Chapelle, in 1748, the island of Cape Breton was restored to France.

After the treaty, Great Britain began to pay more attention to Nova Scotia, which had hitherto been settled relation almost exclusively by the French, who, upon every rupture between the two countries, were accused of violating their neutrality. In order to introduce a greater proportion of English settlers, it was now proposed to colonize there a large number of the soldiers who had been discharged in consequence of the disbanding of the army, and in the latter part of June, 1749, a company of nearly 4000 adventurers of this class was added to the population of the colony.

To every private was given fifty acres of land, with ten additional acres for each member of his family. A higher allowance was granted to officers, till it amounted to six hundred acres for every person above the degree of captain, with proportionable allowances for the number and increase of every family. The settlers were to be conveyed free of expense, to be furnished with arms and ammunition, and with materials and utensils for clearing their lands and erecting habitations, and to be maintained twelve months after their arrival, at the expense of the government.

The emigrants having been landed at Chebucto harbor, under the charge of the Honorable Edward Cornwallis, whom the king had appointed their governor, they immediately commenced the building of a town, on a regular plan, to which the name of Halifax was given, in honor of the nobleman who had the greatest share in funding the colony. The place selected for the settlement possessed a cold, sterile and rocky soil, yet it was preferred to Annapolis, as it was considered more favorable for trade and fishery, and it likewise possessed one of the finest harbors in America. “Of so great importance to England was the colony deemed, that Parliament” continued to make annual grants for it, which, in 1755, had amounted to the enormous sum of nearly two millions of dollars.

But although the English settlers were thus firmly established, they soon found themselves unpleasantly situated. The limits of Nova Scotia had never been defined, by the treaties between France and England, with sufficient clearness to prevent disputes about boundaries, and each party was now striving to obtain possession of a territory claimed by the other. The government of France contended that the British dominion, according to the treaty which ceded Nova Scotia, extended only over the present peninsula of the same name; while, according to the English, it extended over all that large tract of country formerly known as Acadia, including the present province of New Brunswick. Admitting the English claim, France would be deprived of a portion of territory of great value to her, materially affecting her control over the River and Gulf of St. Lawrence, and greatly endangering the security of her Canadian possessions.

When, therefore, the English government showed a disposition effectually to colonize the country, the French settlers began to be alarmed; and though they did not think proper to make an open avowal of their jealousy, they employed their emissaries in exciting the [Mi’kmaq] to hostilities in the hope of effectually preventing the English from extending their plantations, and, perhaps, of inducing them to abandon their settlements entirely. The [Mi’kmaq] even made attacks upon Halifax, and the colonists could not move into the adjoining woods, singly or in small parties, without danger of being shot and scalped, or taken prisoners.

In support of the French claims, the governor of Canada sent detachments, which, aided by strong bodies of [Mi’kmaq] and a few French Acadians, erected the fort of Beau Sejour on the neck of the peninsula of Nova Scotia, and another on the river St. John, on pretence that these places were within the government of Canada. Encouraged by these demonstrations, the French inhabitants around the bay of Chignecto rose in open rebellion against the English government, and in the spring of 1750 the governor of Nova Scotia sent Major Lawrence with a few men to reduce them to obedience. At his approach, the French abandoned their dwellings, and placed themselves under the protection of the commandant of Fort Beau Sejour, when Lawrence, finding the enemy too strong for him, was obliged to retire without accomplishing his object.

Soon after, Major Lawrence was again detached with 1000 men, but after driving in the outposts of the enemy, he was a second time obliged to retire. To keep the French in check, however, the English built a fort on the neck of the peninsula, which, in honor of its founder, .was called Fort Lawrence.Still the depredations of the [Mi’kmaq] continued, the French erected additional forts in the disputed territory, and vessels of war, with troops and military stores, were sent to Canada and Cape Breton, until the forces in both these places became a source of great alarm to the English.

At length, in 1755, Admiral Boscawen commenced the war, which had long been anticipated by both parties, by capturing on the coast of Newfoundland two French vessels, having on board eight companies of soldiers and about 35,000 dollars in specie. Hostilities having thus begun, a force was immediately fitted out from New England, under Lieutenant Colonels Monckton and Winslow, to dislodge the enemy from their newly erected forts. The troops embarked at Boston on the 20th of May, and arrived at Annapolis on the 25th, whence they sailed on the 1st of June, in a fleet of forty-one vessels to Chignecto, and anchored about five miles from Fort Lawrence.

On their arrival at the river Massaguash, they found themselves opposed by a large number of regular forces, rebel Acadians, and [Mi’kmaq], 450 of whom occupied a block-house, while the remainder were posted within a strong outwork of timber. The latter were attacked by the English provincials with such spirit that they soon fled, when the garrison deserted the block-house, and left the passage of the river free. Thence Colonel Monckton advanced against Fort Beau Sejour, which he invested on the 12th of June, and after four days bombardment compelled it to surrender.

Having garrisoned the place, and changed its name to that of Cumberland, he next attacked and reduced another French fort near the mouth of the river Gaspereau, at the head of Bay Verte or Green Bay, where he found a large quantity of provisions and stores, which had been collected for the use of the [Mi’kmaq] and Acadians. A squadron sent against the post on the St. John, found it abandoned and destroyed. The success of the expedition secured the tranquility of all French Acadia, then claimed by the English under the name of Nova Scotia.

The peculiar situation of the Acadians, however, was a subject of great embarrassment to the local government of the province. In Europe, the war had begun unfavorably to the English, while General Braddock, sent with a large force to invade Canada, had been defeated with the loss of nearly his whole army. Powerful reenforcements had been sent by the French to Louisburg and other posts in America, and serious apprehensions were entertained that the enemy would next invade Nova Scotia, where they would find a friendly population, both European and [Mi’kmaq].

The French Acadians at that period amounted to Seventeen or eighteen thousand. They had cultivated a considerable extent of land, possessed about 60,000 head of cattle, had neat and comfortable dwellings, and lived in a state of plenty, but of great simplicity. They were a peaceful, industrious, and amiable race, governed mostly by their pastors, who exercised a parental authority over them; they cherished a deep attachment to their native country, they had resisted every invitation to bear arms against it, and had invariably refused to take the oath of allegiance to Great Britain. Although the great body of these people remained tranquilly occupied in the cultivation of their lands, yet a few individuals had joined the [Mi’kmaq], and about 300 were taken in the forts, in open rebellion against the government of the country.

Under these circumstances, Governor Lawrence and his council, aided by Admirals Boscawen and Mostyn, assembled to consider what disposal of the Acadians the security of the country required. Their decision resulted in the determination to tear the whole of this people from their homes, and disperse them through the different British colonies, where they would be unable to unite in any offensive measures, and where they might in time be-come naturalized to the government. Their lands, houses, and cattle, were, without any alleged crime, declared to be forfeited; and they were allowed to carry with them only their money and household furniture, both of extremely small amount.

Treachery was necessary to render this tyrannical scheme effective. The inhabitants of each district were commanded to meet at a certain place and day on urgent business, the nature of which was carefully concealed from them; and when they were all assembled, the dreadful mandate was pronounced,—and only small parties of-them were allowed to return for a short time to make the necessary preparations. They appear to have listened to their doom with unexpected resignation, making only mournful and solemn appeals, which were wholly disregarded. When, however, the moment of embarkation arrived, the young men, who were placed in front, absolutely refused to move and it required files of soldiers, with fixed bayonets, to secure obedience.

No arrangements had been made for their location elsewhere, nor was any compensation offered for the property of which they were deprived. They were merely thrown on the coast at different points, and compelled to trust to the charity of the inhabitants, who did not allow any of them to be absolutely starved. Still, through hardships, distress, and change of climate, a great proportion of them perished. So eager was their desire to return, that those sent to Georgia had set out, and actually reached New York, when they were arrested.

They addressed a pathetic representation to the English government, in which, quoting the most solemn treaties and declarations, they proved that their treatment had been as faithless as it was cruel. No attention, however, was paid to this document, and so guarded a silence government was preserved by the government of Nova Scotia, upon the subject of the removal of the Acadians, that the records of the province make no allusion whatever to the event.

Notwithstanding the barbarous diligence with which this mandate was executed, it is supposed that the banished number actually removed from the province did not exceed 7000. The rest fled into the depths of the forests, or to the nearest French settlements, enduring incredible hardships. To guard against the return of the hapless fugitives, the government reduced to ashes their habitations and property, laying waste even their own lands, with a fury exceeding that of the most savage enemy.

In one district, 236 houses were at once in a blaze. The Acadians, from the heart of the woods, beheld all they their homes possessed consigned to destruction; yet they made no movement till the devastators wantonly set their chapel on fire. They then rushed forward in desperation, killed about thirty of the incendaries, and then hastened back to their hiding-places.

But few events of importance occurred in Nova Scotia during the remainder of the French and Indian War, at the close of which, France was compelled to the transfer to her victorious rival, all her possessions on the American continent. Relieved from any farther apprehensions from the few French remaining in the country, the provincial government of the province made all the efforts of which it was Capable to extend the progress of cultivation and settlement, though all that could be done was insufficient to fill Up the dreadful blank that had already been made.

After the peace, the case of the Acadians naturally came Under the view of the government. No advantage had been derived from their barbarous treatment, and there remained no longer a pretext for continuing the persecution. They were, therefore, allowed to return, and to receive lands on taking the customary oaths, but no compensation was offered them for the property of which had been plundered. Nevertheless, a few did return, although, in 1772, out of a French population of seventeen or eighteen thousand which once composed the colony, there were only about two thousand remaining.

In 1758, during the administration of Governor Lawrence, a legislative assembly was given to the people of Nova Scotia. In 1761 an important [indigenous] treaty was concluded when the natives agreed finally to bury the hatchet, and to accept George III, instead of the king formerly owned by them, as their great father and friend. The province remained loyal to the crown during the war of the American Revolution, at the close of which, its population was greatly augmented by the arrival of a large number of loyalist refugees from the United States. Many of the new settlers directed their course to the region beyond peninsula, which, thereby acquiring a great increase of importance, was, in 1784, erected into a distinct government, under the title of New Brunswick. At the same time, the island of Cape Breton, which had been united with Nova Scotia since the capture of Louisburg in 1748, was erected into a separate government, in which it remained until 1820, when it was re-annexed to Nova Scotia.

The most interesting portions of the history of Nova Scotia, it will be observed, are found previous to the peace of 1763, which put a final termination to the colonial wars between France and England. Since that period the tranquillity of the province has been seldom interrupted, and, under a succession of popular governors, the country has continued steadily to advance in wealth and prosperity.

In 1729 the colony (of Newfoundland) was withdrawn from its nominal dependence on Nova Scotia, from which period until 1827 the government of the island was administered by naval commanders appointed to cruise on the fishing station, but who returned to England during the winter. Since 1827 the government has been administered by resident governors; and in 1832, at the earnest solicitation of the inhabitants, a representative assembly was granted them.”

Willson, Marcius. “American history: comprising historical sketches of the Indian tribes”. Cincinnati, W. H. Moore & co.; 1847. https://www.loc.gov/item/02003669/