The bridge over the Canal at Portland Street was reconstructed under the direction of Street Superintendent Bishop, and the hollow filled in with material excavated from the water trenches. The sturdy stones on both sides which are now visible only on the northern side, are from the ruins of the Canal Locks, and bear the familiar 7-point etchings of stone-cutters of a bygone day. The stones were set in position by Messrs. Synott and Barry. Thus went the last of our downtown wooden bridges.

The railway bridge over the Narrows, which had been repaired in the previous year, collapsed on the night of July 23rd. The piles must have been very unstable because a large section extending from the Draw to the Halifax side simply floated away in the calm weather then prevailing. Many residents are still alive who had walked across a few hours before.

The old [Mi’kmaq] legend about the curse pronounced upon a crossing over the Narrows, was a well-known tradition in last century. The story goes back to the days before the settlement of Halifax. It seems that in the dim and distant past, a lovely [Mi’kmaq] girl was courted by two braves, one of whom was rich and more powerful than the other. The maiden’s heart, however, was inclined towards the poor one, who finally won her for his bride. They spent their happy honeymoon on the eastern side of Chebucto harbor, near the Narrows.

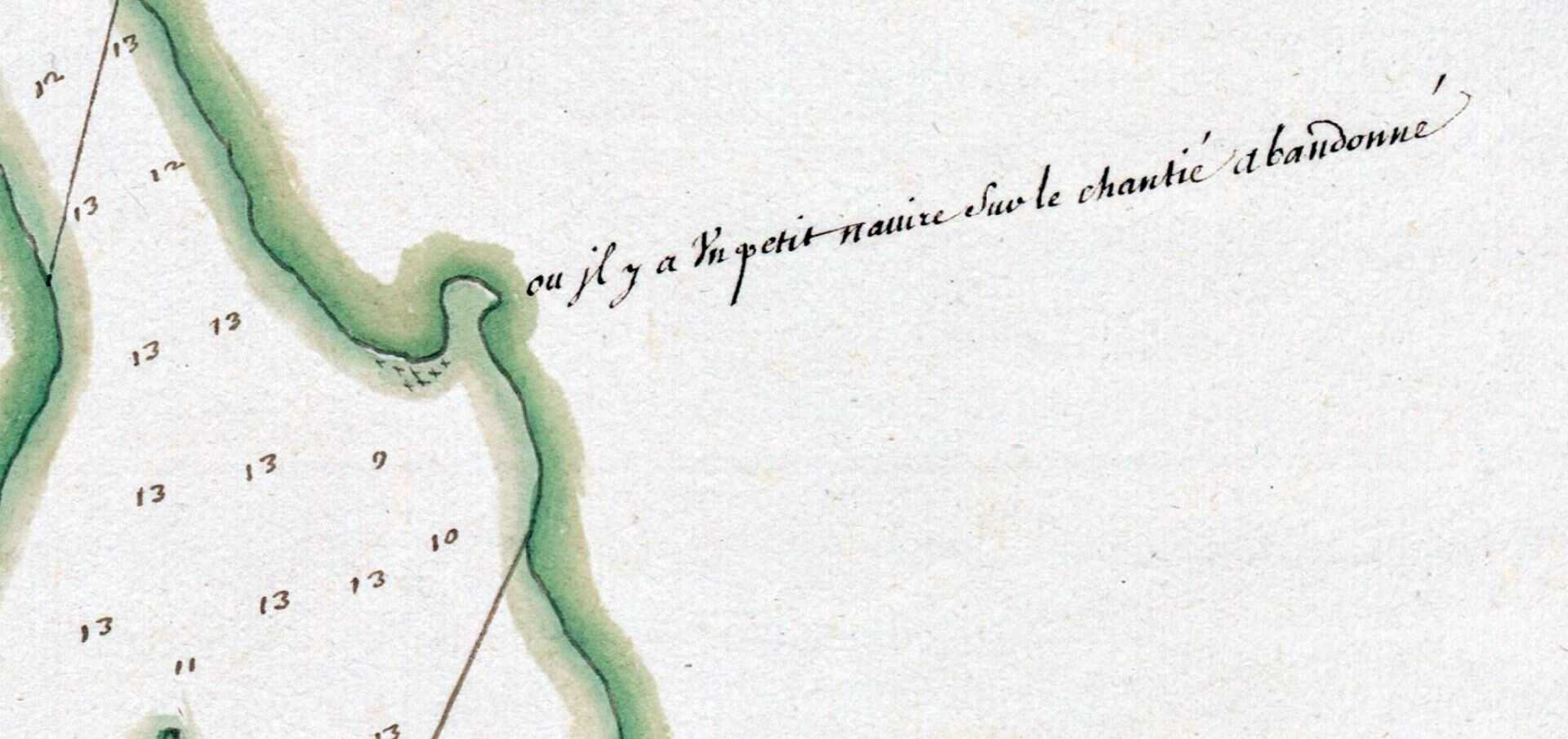

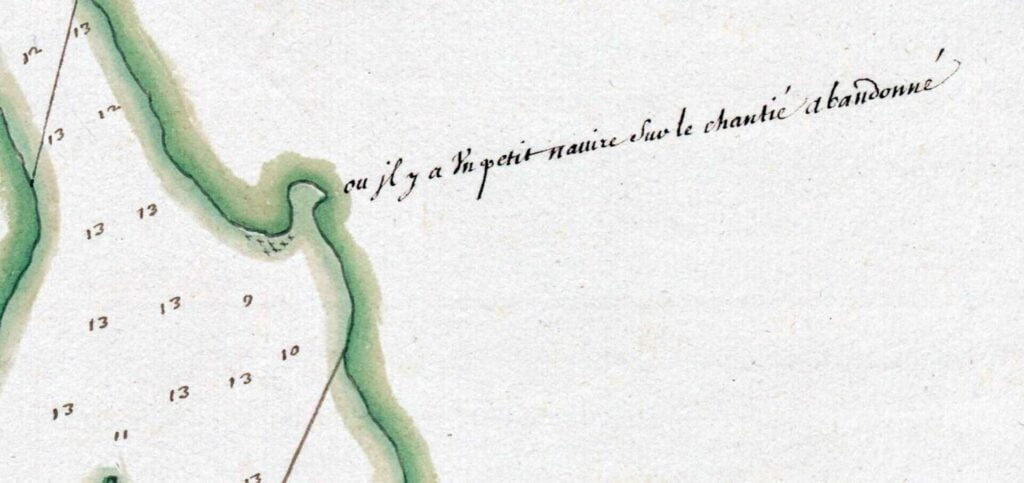

According to the legend, the Narrows was then bridged over by a [Mi’kmaq] construction of poles extended, and resting on canoes, to which they were fastened. These canoes were kept in place by heavy stones hung from ropes long enough to reach the deeper water. In the winter seasons, or in times of warfare, this primitive bridge was removed and the passage left open.

The unsuccessful lover disappeared, and was supposed to have gone on a hunting trip. But one night the bride was wakeful and uneasy. She rose, threw a blanket about her, and passed from the wigwam out into the cool midnight air, hoping that the quiet would bring back her repose. As she strolled towards the shore, a man sprang suddenly from behind a tree, and seized her in his arms. At once he bounded to the beach and on the bridge, while the young bride’s cries for help rang on the air, and wakened her husband and others of the tribe.

Grasping his hatchet, the husband rushed out, only to see his rival carrying away what was most precious to him. He also flew to the bridge, but by that time the rival was half-way across and, while firmly holding his prize, had plucked a hatchet from his belt and with rapid strokes, began cutting the bridge in twain.

A few slashes on the mooring ropes of the canoes, more blows on the poles connecting it with its neighbor, and the bridge parted. The severed ends were then rapidly swept downward by the swiftly flowing waters.

The western end on which stood the abductor and his now fainting prize soon touched the shore. He leaped on the beach with his burden, and was soon lost to sight in the pathless forest.

On the opposite side, the enraged and despairing husband, with bitter curses upon his foe and upon the severed bridge, threw himself into the rushing tide, and was swept down into the night.

Next morning he reappeared at the camp but his reason had fled. He spent the remainder of his days wandering about the shore, muttering over and over again the name of his bride, the villain who had betrayed him and repeating these words: “The first in storm, the second in darkness and the third in blood“.

The collapsing of the railway bridge left stranded in Dartmouth about 35 freight cars whose contents were subsequently transported to Halifax by lighters. Telephone and telegraph wires strung along the bridge, also went out of commission and disrupted communication service for a time. At Dartmouth public meetings were held to discuss the advisability of reconstructing the bridge once more, but the majority of townsfolk favored the building of a railway from Windsor Junction to Dartmouth. This proposal was forwarded to authorities at Ottawa. Councillor A. C. Johnston and Benjamin Russell went thither to urge its adoption.

All the while the water project was going steadily forward. When Portland Street was being trenched in 1893, workmen unearthed a skull and some human bones. In sections of town where there were solid slate-rock formations, hand-drills were replaced by steam-drills. The latter method, which greatly expedited progress was under the supervision of A. A. Hayward, Manager of the American Hill gold mine at Waverley. Prince Street was one of the toughest. Almost the whole block had to be blasted. Similar formations were encountered on Dundas Street south of Queen, and in the stretches of Prince Albert Road and Portland Street bordering St. James Church.

In 1894 the first street signs were put up, and certain changes made in street names. The southern section of Prince Edward Street was changed to Prince Street, and the northern part changed to Edward Street. Colored Meeting Road was changed to Crichton Avenue. The present Prince Albert Road, hitherto called Portland Street, was changed to Canal Street and then ran from the shore to the Town limits. Portland Street was lined up as at present. Bishop Street, which extended from the Starr Factory to Burton’s Hill, was incorporated into Pleasant Street.

The new Post Office was opened in May. On the opposite corner the Sterns family built their second brick structure (present Dartmouth Furnishers), and in October returned to do business at the stand Luther Sterns had vacated 30 years previously. Rhodes Curry and Co., were the contractors. Edward Elliot was architect.

In June the stone-crusher went into operation, breaking up heavy rocks to macadamize the streets at a low cost. Daniel Brennan was Policeman No. 2. William Webber of Pine Street was engaged as a Watchman from 12 o’clock until eight in the morning. Up to that year, the Town was without police protection after midnight. A drinking fountain, donated by the local branch of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, with outlets for humans, horses and dogs, was erected on Steamboat Hill. Another drinking trough for horses, donated by J. Walter Allison, was set up on the north side of the road near 97 Pleasant Street.

John T. Walker erected St. Peter’s Hall on Ochterloney Street, and a two-roomed school at Woodside opposite 217 Pleasant Street. John N. McElmon raised the roof of Greenvale School and inserted a second storey with four additional rooms. The same contractor built a spacious Hall for the Turtle Grove Recreation Club (now apartments at 32 Dawson Street). At 51 Pleasant Street a double dwelling was completed for James Simmonds and A. E. Ellis. More bones were unearthed that summer when excavating for St. James’ new Manse. A commencement was made on the branch railway from Windsor Junction. A private telephone wire was strung on electric light poles, connecting Town Hall with the four schools.

Dartmouth oarsmen like Colin McNab and Charles Patterson were competing in the Lorne Club and other regattas at Halifax. The ‘Atlantic Weekly” suggested that similar programs be carried out at First Lake. In September, Woodside Refinery Club held a Saturday afternoon regatta over a course from the Sugar Refinery northward and return. Only Woodside employees participated.

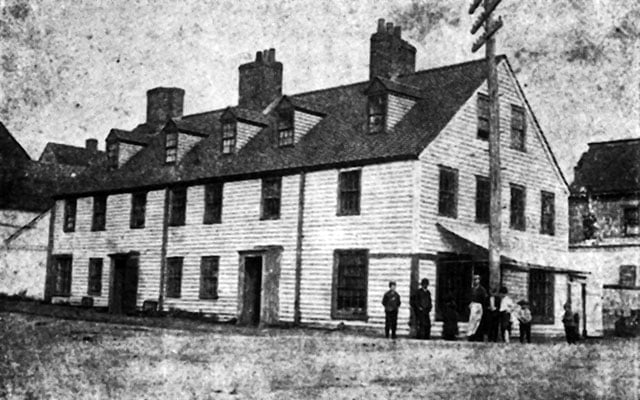

This is what the old Inn of John Skerry looked like about 1892. The premises were then owned by John R. Graham, and the building divided to accommodate three families. In last century the sidewalk was much lower, and the Ochterloney Street entrance was reached by three layers of steps. The chimneys came up from three large fireplaces in the basement which evidently had served as a kitchen. Timbers twelve inches square support this building, and hand-hewn laths may still be seen in the walls. Note the clapboards on the sides, and the “Nova Scotia dormer windows” typical of 19th century houses throughout the Province. In the early 1890s Thomas Cushion kept a butcher shop at this corner. Man in white apron may be Albert Yetter. Lame “Johnnie” Wilson with his supporting stick and summer straw-hat, is leaning against the corner-board. The fence on the right is plastered with praises of patent medicines, and the low building adjoining is the old curiosity shop of Alec Pitts who used to display his second-hand furniture on the Water Street sidewalk in favorable weather.

This is the first St. Peter’s School erected about 1841, and regarded as one of the principal schools of Dartmouth until 1880. Boys and girls attended. This hall was built near St. Peter’s old church in the same manner as was the old parish school hall of Christ Church, because in the early days schools were usually of a denominational character and were fostered by the clergy. Of course any children were admitted upon payment of the tuition fee, until after the Free School Act when these institutions became public schools of the Town. Some teachers in old St. Peter’s included William Lawlor, John McDonald, David Walsh, Mr. Thorpe, Mr. Kelly, Mr. Hipp, John Cashen, Miss O’Toole, Miss Mary Holt, Miss Cassie Downey. St. Peter’s Temperance Society was organized here in 1885. The little building was removed from Ochterloney Street in 1894 to make room for the new St. Peter’s Hall.

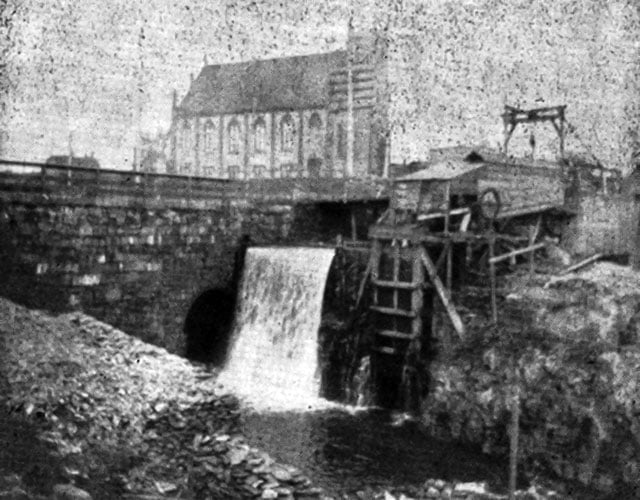

This is the new Canal bridge and stone-crusher after it began to function in 1894. Both sides of the structure were made of heavy blocks of stone mostly from abandoned Canal Locks. Afterwards the middle part of the bridge was filled in with surplus slate-rock excavated from water-trenches, and also with material from the streets. The archway at the base is 12 feet high, built of bent iron rails and then covered with stone. In all, about 8 tons of iron rails, 775 tons of heavy stone and 3,258 cartloads of filling were used on this job. The total cost was $943.01. From about the year 1890, small stone was broken on a portable breaker which operated in different sections of Town to crush the surface pieces of whinstone then abundant everywhere. Previous to 1890, stone was broken with hand-hammers by unemployed men who were paid at the rate of three cents per bushel. In the 1880s they used the narrow level area on the east side of Prince Albert Road midway between the MicMac Club and Carter’s Corner. They had no protection from the weather.