From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

Christ Church at Dartmouth was consecrated by Bishop Inglis on Sunday, August 21, in the presence of a numerous gathering including Hon. Michael Wallace, Chief Justice Archibald and “other respectable individuals”. As the Rev. Charles Ingles had gone to Sydney in 1825, the parish was without a resident rector until Rev. Edward L. Benwell, an Englishman, came to Dartmouth in December of 1826.

The first regatta on Halifax harbor was held in the summer of 1826 as part of the program arranged for the visit of Lord Dalhousie. All the warships in the harbor and numerous small craft were bedecked in colors for the occasion. The prize for first-class sailing boats was won by Admiral Lake, who steered the craft himself. The fishermen’s races, however, pulling over the long course around George’s Island, created much more interest.

Besides the rowing contests, there was a canoe race open to [Mi’kmaq]. It was a new and novel sight for the crowds of spectators to see several canoes impelled with surprising velocity by [Mi’kmaq] in their native costume with their long black hair flying in the wind, and to hear their exciting shrieks of the most extraordinary yells as they dashed down the harbor.

The regatta was such a decided success that it promised to become an annual affair. Money prizes were awarded the winners, chiefly in the canoe and rowing events.

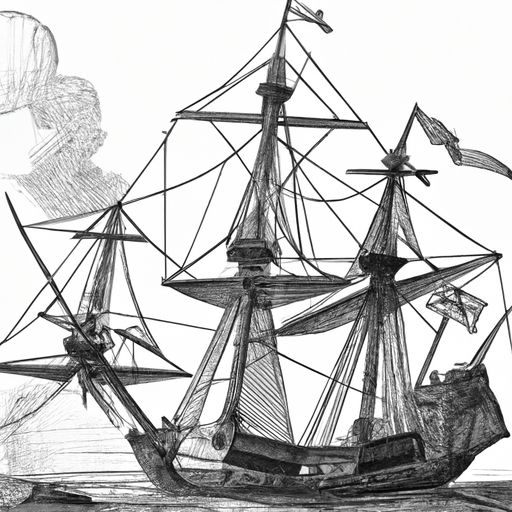

Shipbuilding continued to thrive in Dartmouth. At the yards of Thomas Lowden that July, there was completed a 320-ton ship named the “Atlantic”. She was 104 feet long. Despite the early hour of 7.30 A.M., throngs came from Halifax to witness the launching. The newspaper report says that the masts of the Atlantic” were festooned with flags, and her decks were filled with the adventurous. As she moved majestically down the ways and plunged headlong into the water which rose and danced around her, loud huzzas were raised from point to point, softened Into melody by the martial music of the Regimental band stationed “on the opposite side of the creek”.

This description suggests that the location of Lowden’s yard was near the outlet of the present Canal stream, perhaps on the sheltered beach just south of the railway trestle.

There must have been a second keel already laid in that yard, for on the last day of November, 1826, there was another gala launching from Lowden’s. This ship was the 400-ton “Pacific”, built for a Halifax Company, and intended for the South Sea whale fisheries. She was constructed of the best Musquodoboit oak, and was copper-sheathed and copper fastened.

Considerable exertion had to be used before the vessel started to move, but after the first few impulses, she moved gracefully down the skids into the water. She was then towed by the Team-Boat to Cunard’s wharf to be fitted out.

The Quaker Society was still flourishing in 1826, for in that year they expelled six of their Dartmouth members. Three Elliots and three Colemans were involved. The Elliot family were no doubt reared as Quakers by their mother whose maiden name was Almy Green. According to Judge Benjamin Russell’s autobiography, Almy was the daughter of an old Quaker preacher who ministered to the Society of Friends at the Dartmouth Quaker Meeting House, late in the 1700’s.

Almy Green was the senior Mrs. Jonathan Elliot. Two of her sons, Jonathan and Stephen Elliot married Charlotte, and Jane Collins respectively. Another son Benjamin, married Ann Coleman, granddaughter of Seth Coleman.

Of the Coleman boys, George and James Coleman, brothers of Ann, married Jane Storey and Sarah Bell, respectively. These marriages had taken place over a period of years.

But the point to be noted is that they were performed by Anglican clergymen. Evidently, according to Quaker principles, this was unorthodox.

The Quaker Society must have mulled over such violation for many months, because it was not until October of 1826 that the following decree came forth from Charles G. Stubbs, the Secretary in Nantucket:

“Information being received that George and James Coleman, Jonathan, Benjamin and Stephen Elliot, Members of this Meeting, residing in the Province of Nova Scotia, have joined in marriage contrary to the Established Order of our Society—it is the conclusion of this Meeting in accordance with the advice from our Quarterly Meeting on the subject, to disown them as Members of our Religious Society, with which the Women’s Meeting unite, and Mark Coffin and Tenas Gardiner are appointed to inform them of their right to appeal and report at a future Meeting.

“We unite with the Women in the disownment of Ann Elliot, daughter of John Brown Coleman, residing in the Province of Nova Scotia, for marrying contrary to the Established Order of our Society”.

The Shubenacadie Canal Company, incorporated in 1826, brought the biggest boom to Dartmouth in 40 years. The purvance of this enterprise made a great change in the topography of the town, and contributed materially to its early growth by attracting scores of skilled and unskilled workmen, many of whom decided to become permanent residents.

When Canal shares were put on the market that spring, over £1000 was subscribed in the first few weeks. Of this amount nearly £700 was taken up by Dartmouthians, among whom were Samuel Albro, George B. Creighton, Lawrence Hartshorne, Edward Warren, Andrew Malcom, William Donaldson, John Elliot, Benjamin Elliot, William Foster, Henry Y. Mott, Leslie Moffat, Edward H. Lowe, Joseph Moore, Alexander Farquharson, John Farquharson, jr., William Wilson, Charles Reeves, J. W. Reeves, John D. Hawthorn and John Tapper. The value of a share was £25. To the subscription list, the Legislature voted a sum of £15,000 which was to be paid according as the work progressed. Few shares were sold elsewhere in the Province, many regarding the Canal scheme as impracticable and even fantastic.

The great work of the Canal was commenced with appropriate ceremonies in the isthmus between Lake Mic-Mac and take Charles on the afternoon of Tuesday, July 25, 1826, when the first sod was turned by Lord Dalhousie, Governor-General of British North America, who was visiting Halifax that summer. Others present with their ladies among the 2,000 spectators were Lieutenant-Governor Sir James Kempt, Rear Admiral Lake, Officers of the Regiments at Halifax, members of the Government and principal officials of the Canal Company.

Dartmouth must have been alive with activity early that summer morning as the “Grinders’’ and the Team-Boat kept disembarking Companies of infantry with their bands, and the squads of artillerymen drawing heavy field pieces. Then came the various Halifax Masonic Lodges with their banners and regalia to re-form their ranks at the ferry for the dusty three-mile march to Port Wallace.

Arriving at the spot chosen for the excavation, the above-mentioned bodies formed themselves into a hollow square about 1.30 P.M., when a bugle from the main road sounded the approach of Their Excellencies. At once the artillery boomed out a 19-gun salute, following which the band of the Rifle Brigade struck up “God Save the King”. Hon. Michael Wallace, 83-year-old master of ceremonies, then escorted the Earl of Dalhousie under an arch formed by the Masons, and delivered his introductory address, part of which was as follows:

“As I have been honored with the office of President, I cannot be a silent spectator of this first step of this important work. I have the confidence and pride to style myself the father of this project. It originated in my mind long before many of those who hear me, were born…..

“I cannot expect to have many years added to my life, but it is not impossible that I may yet view the progress and even the completion of this great design …. Our children, I venture to prophecy, will bless us for the undertaking, and our posterity will find it one of the best legacies bequeathed to them by their ancestors……”

Lord Dalhousie then threw out a few shovelfuls of earth, and pronounced the work commenced. After His Excellency’s address, and a prayer pronounced by the Anglican Bishop, the cannon fired another salute. The whole of this interesting ceremony closed with the Buglers playing “The Meeting of the Waters”, and with three hearty cheers from the assembled gathering.

Returning to Dartmouth, the carriages of the principal guests stopped at “Poplar Hill” where they were entertained at a luncheon given by Lawrence Hartshorne. The Canal celebration concluded with a ball and supper at Government House in the evening.