In 1790, the Nova Scotia Assembly passed impeachment articles against two puisne judges, Isaac Deschamps and James Brenton, accusing them of illegal and corrupt acts. The charges stemmed from alleged incompetence, partiality, and dishonesty, including lying during an earlier inquiry. The trial before the Committee of the Privy Council in London resulted in the judges’ exoneration. Despite the failure, the impeachment attempt sheds light on colonial legal systems, judicial professionalization, and the relationship between judges and local power structures. In particular, it highlights the lack of separation of powers between the executive and judiciary in colonial governance.

The judges received staunch support from the executive, revealing the limited control the elected branch had over judicial appointments and dismissals. One of the impeachment articles, focusing on a criminal case involving Christian Bartling, criticized Judge Brenton’s handling of the bail process and re-committal following the failure to secure an indictment. However, the criticisms were largely unfounded, with the Privy Council finding no fault in Brenton’s actions. The Bartling case, marked by political tensions and racial prejudice, exemplified the complexities of colonial justice and the influence of local politics on legal proceedings. Despite attempts to discredit the judges, the impeachment proceedings failed to tarnish their reputations or undermine their authority.

“Isaac Deschamps and James Brenton, puisne judges of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court [NSSC], had, charged the colonial Assembly in April 1790, committed “divers illegal, partial, and corrupt acts” such as to justify “Impeachment” for “High Crimes and Misdemeanors.”‘ These words come from the preamble to a list of seven “articles of impeachment” passed by the Nova Scotia Assembly on 5-7 April 1790. The seven articles, distilled from thirteen draft articles which had been introduced on 10 March, listed ten cases in which the judges were alleged to have acted incompetently or partially, or both, and also included accusations that they had lied to the Lieutenant-Governor’s Council of Twelve when it had conducted an inquiry into some of the allegations two and a half years earlier. The “trial” of the judges on these articles of impeachment took place before the Committee of the Privy Council for Trade and Plantations in London, and resulted in their complete exoneration. This was one of only two occasions on which pre-confederation Canadian colonial assemblies passed “impeachment” articles against superior court judges, and both failed. Judges were removed, but by executive power, for they did not hold their commissions on “good behavior” and, thus, enjoy independence. The best known Canadian examples of executive removal are Robert Thorpe and John Willis in Upper Canada, but three other British North American judges were removed by colonial executives-Caesar Colclough and Thomas Tremlett in Prince Edward Island, and Richard Gibbons in Cape Breton.’

The Nova Scotia Assembly’s failure matters much less than the attempt; the long, drawn out saga of the efforts to censure and remove the NSSC judges is of interest to historians of colonial legal systems. It represents a chapter in the history of judicial professionalization, for much of the rhetoric aimed at the judges, especially Deschamps, concerned their basic competence. The event also reveals the role played by colonial judges within local power structures. The modern notion of a separation of powers between executive and judiciary was no part of the British system of colonial governance, with judges expected to be firm supporters, indeed active members, of government and receive in turn the backing of the executive. Hence, the Nova Scotia judges received unqualified support from the Lieutenant-Governor and his Council. Conversely, the failed impeachment shows that the elected branch of the constitution had as little control over the dismissal of judges as it did over their appointment. While the impeachment crisis is a significant event in Canadian legal history, and while that is the focus of the article, the events of the late 1780s and early 1790s also contribute to our understanding of the province’s general history, in particular of the transformations that took place after the American revolution.”

Article 2: R v Bartling (and R v Small)

Article 2 principally concerned R v Bartling, one of only two criminal cases among the allegations, the other being R v Small, which was used not so much as a ground of complaint but as a contrast to the Bartling case. Bartling and Small were the two cases from 1789 that, I suggest above, provided part of the catalyst for a successful re-raising of the judges’ question early in 1790, at a time when Parr believed the crisis was long over.

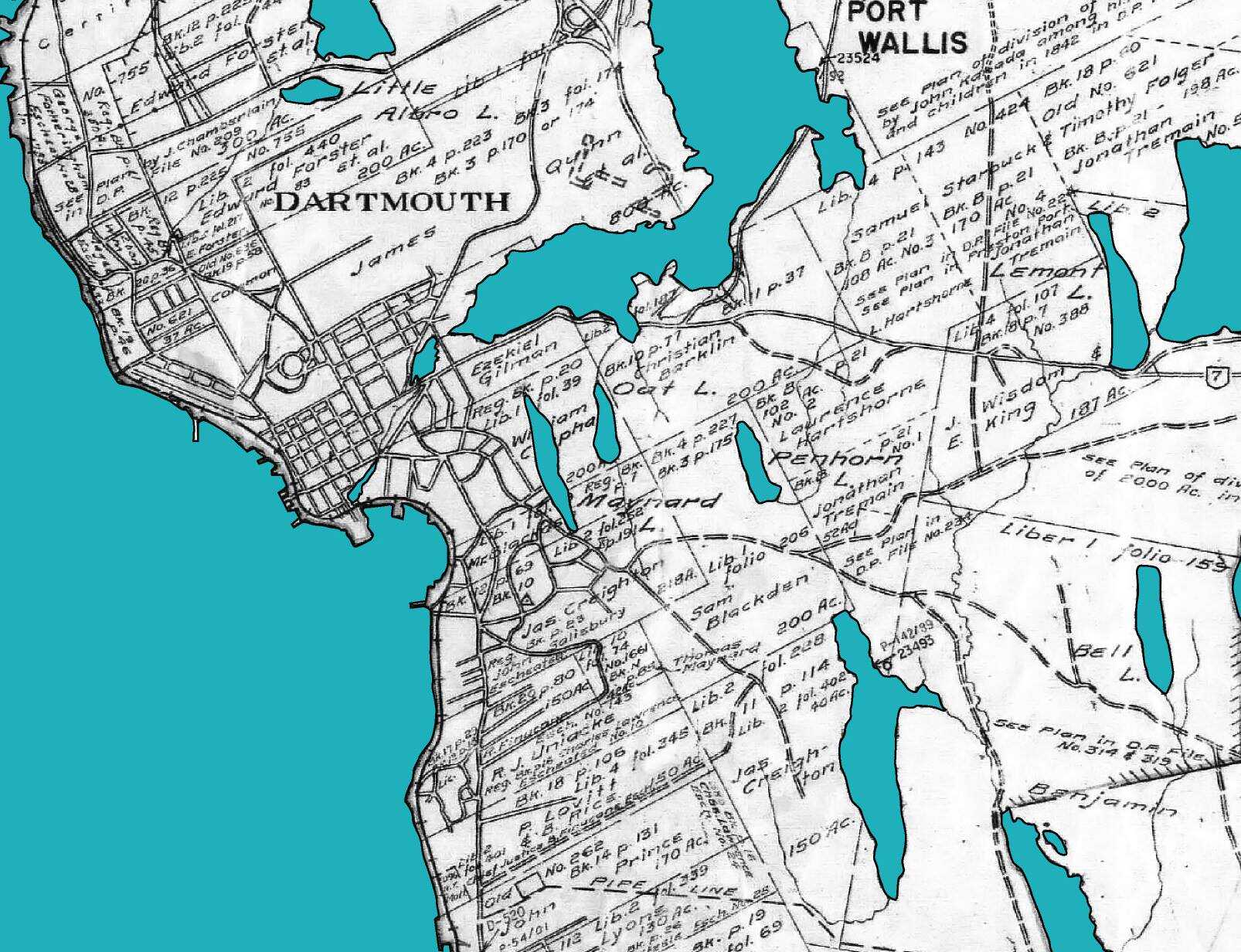

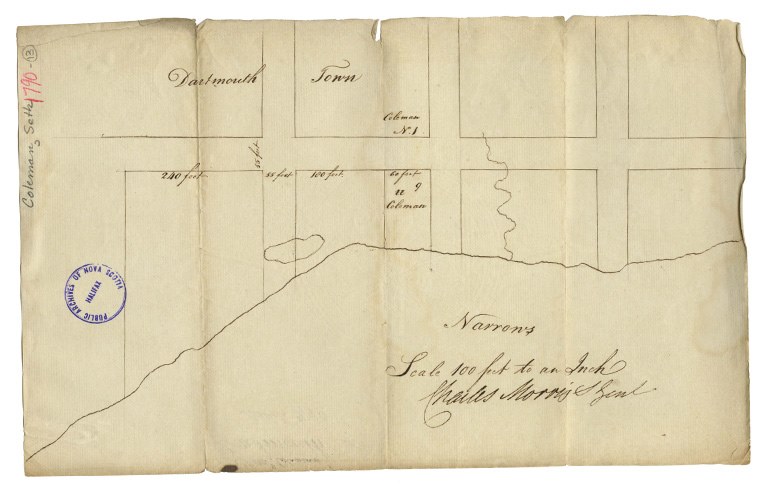

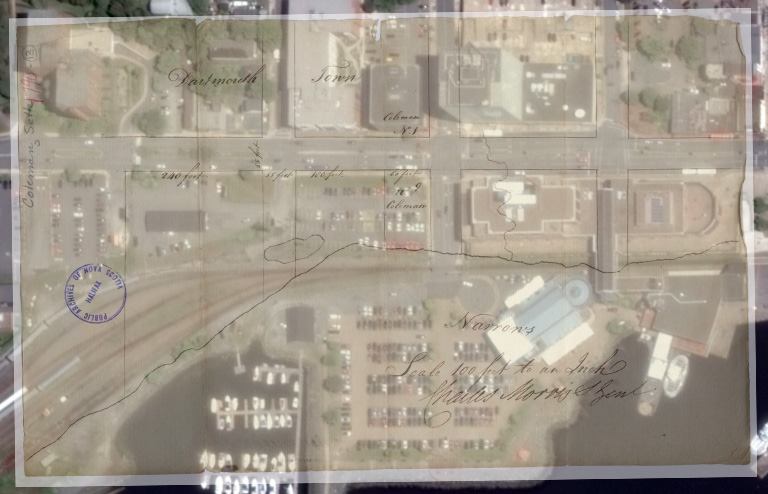

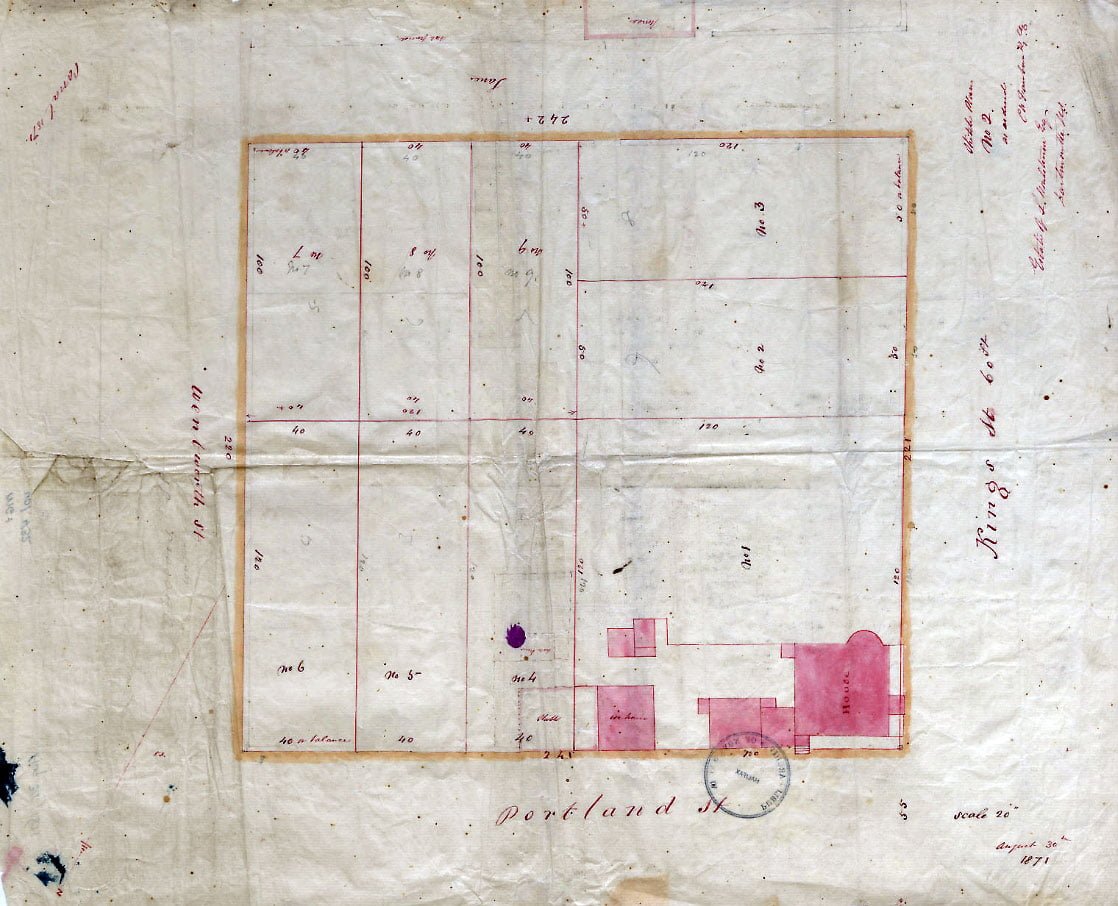

Christian Bartling was a very early settler in Halifax/Dartmouth and, by the 1780s, a substantial landowner on the Dartmouth side of the harbour. In May 1789 he got into boundary disputes with Jonathan Foster, Nathaniel Macy, and Barnabas Swain, all recent arrivals and all members of a group-some 40 families-of Nantucket Quaker whalers who had moved to the area in 1785. Although encouraged and indeed subsidized by Parr and his Council, the move was controversial both in London and Halifax in part because a considerable amount of land had been expropriated for them from absentee proprietors and in part because this particular economic development project was seen as aiding Americans and evading the imperial Navigation Acts.”‘ Bartling, apparently convinced that Swain et al were trespassing, defended his turf with a shotgun, and a considerable amount of shot ended up in Swain. He lost an eye to the assault.

Bartling was remanded for trial by a JP, and an application for release through a writ of habeas corpus in mid-June was denied. He went to trial a month or so later in Trinity Term. Although, as was common, the indictment was prosecuted by Attorney-General Blowers, the grand jury rejected it. When the judges were told this Brenton asked Blowers if he had another charge to prefer, but he did not. In Bartling’s lawyer Martin Wilkins’ words, he “turned his Back upon the Court and remarked that he washed his hands Clear of it and their Honors must decide for themselves.” Solicitor-General Uniacke, also in court, then declared “with some degree of heat” that “he would prefer Bills to.. .Grand Jury after Grand Jury, against Bartling so long as there was a Grand Jury in the Country, until a Bill was found… or until the Prisoner had a Public Trial.” Brenton remanded Bartling, although his further confinement lasted only one day; he was discharged when the court met the following morning. According to lawyer Daniel Wood, Deschamps gave no reasons but told Bartling “that in consideration of his long confinement and Large family they would then release him, without his giving Security, notwithstanding the Grand Jury had tho[ugh]t proper to acquit him, his Crimes appeared to be very enormous, and hoped the indulgence they then gave him would have some good effect upon him.”‘

The second article of impeachment criticized two aspects of Brenton’s handling of this case; Deschamps was not involved in the charges. It complained that Bartling had not been given bail when habeas corpus was applied for, as he should have been for committing a trespass. It was here that a contrast was drawn to R v Small. 4′ William Small was one of a group of black men and women who became involved in an altercation with three young, and drunk, white men returning home from a night of carousing in late November 1788. The whites had assaulted a fiddle player, George Warner, and Warner ran for refuge to Small’s house. When the whites tried to follow Warner in, Small came out armed with a spade. In the melee William Lloyd was struck with the spade and he died almost two months later. A coroner’s jury found that Lloyd had died from the blow inflicted by Small and he was arrested. A week later Small was bailed, by Brenton, with the sureties being William Brenton, the judge’s half-brother, and loyalist merchant Samuel Hart. Article 2 made the contrast between the two cases: Brenton had refused bail to Bartling but he had earlier “bailed a certain William Small, a [black] man, positively charged by, and committed on the Coroner’s Inquest, for [a]… felonious murder.”

The Privy Council made short work of the bail complaint, not even adverting to the contrast with Small. The evidence before the Assembly had made a lot of the fact that Brenton waited a day to hear the habeas corpus application, and the committee simply, and rightly, held that a Judge was not required to hear the application “the moment it is presented to him,” as “[i]t may be often material to enquire for what… crime” a person had committed “before he is brought up in order to be prepared in some sort to judge how it would be either legal or proper to Bail him.” When Brenton did hear the application, he was prepared to grant bail, but no sureties could be found, always a requirement for bail. In the Assembly the prosecution had alleged that Bartling had lost his sureties by the delay, but the evidence also showed, and the committee accepted this, that the reason he could find no sureties was that the men willing to do so were only prepared to stand bail for his appearance in court, not to be answerable for his keeping the peace, because Bartling “was apt to be in liquor.” The committee also adverted to evidence from Halifax sheriff James Clarke that he had summonsed possible sureties to court but they had refused to come.

The committee also noted that the statement in Article 2 that Bartling had been arrested for trespass was inaccurate, that he had been arrested for a felony, a serious assault leading to a wounding. As the indictment put it, Bartling had inflicted “several grievous wounds” and “the sight of one of [Swain’s] eyes” had been “ruined and destroyed.”‘ The committee made nothing more of this mis-statement in the charge, perhaps because if Brenton could have been criticized for anything in this stage of the proceedings it was that he was prepared to bail Bartling at all. The Marian bail laws were in force in Nova Scotia and they made remand the default option in the vast majority of felonies. It was extremely rare for anybody charged with a felony to receive bail-only ten of the more than 700 defendants who appeared in the NSSC at Halifax between 1754 and 1803 were bailed.'” Evidence given before the Assembly suggested that it was known that Parr favoured remand, and thus Brenton had somehow been improperly influenced by the Lieutenant-Governor. But since Brenton granted bail that complaint amounted to naught and did not find its way into the article of impeachment.

All in all the Assembly’s complaint about the bail process was worthless; ironically, as noted, they would have had a stronger case if they had attacked Brenton for not remanding Bartling. There was not even any validity to the contrast with the Small case-the latter was a highly exceptional but nonetheless explicable exercise of discretion, and, given contemporary attitudes towards blacks, criticisms of Brenton were surely a product of racism as much as anything else.

The second principal cause for complaint over the Bartling case was the re-committal following the failure to get an indictment. Certainly it was an unusual proceeding-normally a defendant not indicted or found not guilty was immediately released from custody. Yet there were other cases in which defendants were recommitted and another indictment drawn up, and in this instance Solicitor-General Uniacke declared that he would do so. Questioning of witnesses before the Assembly tried to elucidate testimony to the effect that Brenton remanded Bartling before Uniacke made his declaration, but witnesses were either contradictory or unsure on the point. The committee asserted that a recommittal pending another indictment was “the common practice at the Old Bailey,” and criticized the grand jury’s decision in any event. It was clearly a felony and there seemed to be enough evidence to proceed to trial. The committee could have made more of this point. A marginal note in the proceedings states that if the English “Black Act” was in force in the colony it certainly was a felony. What it did not say was that it was not just a felony, but a capital offence, and it seems surprising that the committee did not pursue this question further, for malicious shooting at somebody was indeed a capital offence in the colony. That they did not do so is perhaps attributable to the problem raised above: Brenton was very much at fault for bailing a person accused of so serious a crime.

It seems likely that the Bartling case became something of a cause celebre because of its political overtones. Neither the loyalists who supported Bartling out of resentment at the American whalers nor the elements in government and the city who sided with the whalers behaved particularly creditably. The JP who initially took down the parties’ depositions, loyalist James Gautier, does not appear to have committed Bartling or issued recognizances to prosecute, as he should have done. It was only later that another JP, William Folger, one of the whalers, did so. Parr, a supporter of the whalers, might well have had an opinion, along with many other people in the city, but as we have seen that opinion cannot have influenced Brenton. The fact that the contrast with Small included the statement that he was “a [black] man” suggests that racism played a role; the contrast of Bartling’s treatment with somebody else’s would not have mattered had not that other person been a black resident.

As already noted, the really questionable decision was the grand jury’s turning back of the indictment. Attorney-General Blowers probably should have had another indictment to put forward, but seems from the evidence given above to have been too peeved, and perhaps surprised, to bother. Solicitor-General Uniacke had to intervene on the spur of the moment; he was a vigorous supporter of the whalers’ move to Dartmouth and obviously wished the law to be used against those who resisted their integration into the community. Initially exasperated at a form of “grand jury nullification,” we can only suppose that he thought better of the politics of preferring another indictment on reflection. But the principal point for our purposes is that the Assembly’s criticisms of Brenton in this case were misplaced. It was a case riven with politics and prejudice, which may have inflamed local passions on all sides, but not one which showed the court in the bad light the Assembly tried to cast on it.

Jim Phillips, “The Impeachment of the Judges of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court, 1787-1793: Colonial Judges, Loyalist Lawyers, and the Colonial Assembly” (2011) 34:2 Dal LJ 265.