Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane. Bye-laws of the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane, 1868. [Halifax, N.S.: s.n.], 1868. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/aeu.ark:/13960/t9184245w

Nova Scotia Hospital

Speech at Dartmouth, May 22 1867

Joseph Howe’s Speech at Dartmouth, May 22nd, 1867, is a passionate lamentation, decrying the loss of Nova Scotian autonomy and self-governance to the Canadian government through confederation. He reminisced about the struggles over decades for self-government fought against British control, highlighting the achievements in areas such as governance, trade, taxation, militia organization, postal services, currency stability, banking, and savings institutions.

“The rifle is the modern weapon, and our people have not been slow to learn the use of it. Organized by their own Government, commanded by their friends and neighbours, 50,000 men have been embodied and partially drilled for self-defence. But now strangers are to control this force—to appoint the officers and to direct its movements.“

He expressed deep concern that these hard-won freedoms and systems were being eroded by the Canadian government, distant and uncaring, imposing its will on Nova Scotia without regard for its unique needs and experiences. He viewed the impending loss of control over crucial aspects of governance, economy, and finance as a betrayal, fearing increased taxation, economic instability, and exploitation of the populace by external interests. All of which came to pass.

“But it is said, why should we complain? We are still to manage our local affairs. I have shown you that self-government, in all that gives dignity and security to a free state, is to be swept away.

The Canadians are to appoint our governors, judges and senators. They are to “tax us by any and every mode” and spend the money. They are to regulate our trade, control our Post Offices, command the militia, fix the salaries, do what they like with our shipping and navigation, with our sea-coast and river fisheries, regulate the currency and the rate of interest, and seize upon our savings banks.

What remains? Listen, and be comforted. You are to have the privilege of “imposing direct taxation, within the Province, in order to the raising of revenue for Provincial purposes.” Why do you not go down on your knees and be thankful for this crowning mercy when fifty per cent has been added to your ad valorem duties, and the money has been all swept away to dig canals or fortify Montreal.”

Howe, one of our leading statesman and also, it appears, our prognosticator in chief, painted a vivid picture of a once-independent Nova Scotia being subjugated and marginalized within the larger Canadian federation, and the dire consequences for its economy, society, and autonomy that would result.

In opposing the British North America Act… (Joseph Howe) always urged that it was not acceptable to the people of Nova Scotia. As an election was soon to be held, to make good his statement Mr. Howe felt that he must organize his forces, and demonstrate beyond dispute that the Province of Nova Scotia was overwhelmingly opposed to the union. He returned early in May, and on May 22nd delivered at Dartmouth the following speech, in which he betrays no loss of his old-time warmth and vigour:

MEN OF DARTMOUTH —

Never, since the [Mi’kmaq] came down the Shubenacadie Lakes in 1750, burnt the houses of the early settlers, and scalped or carried them captives to the woods, have the people upon this harbour been called upon to face circumstances so serious as those which confront them now. We may truly say, in the language of Burke, that “the high roads are broken up and the waters are out,” and that everything around us is in a state of chaos and uncertainty. A year ago Nova Scotia presented the aspect of a self-governed community, loyal to a man, attached to their institutions, cheerful, prosperous and contented. You could look back upon the past with pride, on the present with confidence, and on the future with hope.

Now all this has been changed. We have been entrapped into a revolution. You look into each other’s faces and ask, What is to come next? You grasp each other’s hands as though in the presence of sudden danger. You are a self-governed and independent community no longer. The institutions founded by your fathers, and strengthened and consolidated by your own exertions, have been overthrown. Your revenues are to be swept beyond your control. You are henceforward to be governed by strangers, and your hearts are wrung by the reflection that this has not been done by the strong hand of open violence, but by the treachery and connivance of those whom you trusted, and by whom you have been betrayed.

The [Mi’kmaq] who scalped your forefathers were open enemies, and had good reason for what they did. They were fighting for their country, which they loved, as we have loved it in these latter years. It was a wilderness. There was perhaps not a square mile of cultivation, or a road or a bridge anywhere. But it was their home, and what God in His bounty had given them they defended like brave and true men. They fought the old pioneers of our civilization for a hundred and thirty years, and during all that time they were true to each other and to their country, wilderness though it was. There is no record or tradition of treachery or betrayal of trust among these [Mi’kmaq] to parallel that of which you complain.

Let us, in imagination, do them the injustice they do not deserve, and assume that six of their young men went over and sold them to the Milicetes of New Brunswick or to the Penobscots of Maine. What would have happened? Would the old men, on their return, have folded them to their bosoms, or the young braves have trusted them again? No,—the tomahawk and the fire would have been their reward, and the duty of honour and good faith would have been illustrated by a terrible example. The race is mouldering away, but there is no stain of treason on its traditions. Even in its day of decadence and humiliation it challenges respect, and when the last of the [Mi’kmaq] bows his head in his solitary camp and resigns his soul to his Creator, he may look back with pride upon the past, and thank the “Great Spirit” that there was not a Tupper or a Henry, an Archibald or a McCully in his tribe.

Look again at that dreary and uncertain hundred and thirty years which preceded the foundation of Halifax, which Beamish Murdoch (whose book it always gives me pleasure to recommend) so carefully delineates, and you will find that even among the earlier explorers and occupants of our western counties, fitful and uncertain as were their fortunes, there were fidelity and honour. When Halifax and Dartmouth were founded, when there were but a few thousand men upon this harbour, living within palisades and defended by block-houses—when an impenetrable wilderness lay behind them, and the woods were full of [Mi’kmaq] and of French, we hear of no treachery, of no betrayal of trust.

The “forefathers of our hamlets” were true to each other. They toiled in the belief that they were founding a noble Province that their posterity would govern. The loyalists, who came in great numbers during the revolutionary war, cherished the same belief, and never dreamed that the Province they were strengthening by their intelligence and industry was to be wrested from their descendants and governed by Canadians. The Scotch emigrants who flowed into our eastern counties came, attracted by a name they loved, to govern themselves, and transmit the country untrammelled to their descendants. The Irish, fleeing from a land that had been swindled out of its legislature, fondly believed that here they would find the freedom and the self-dependence they had sighed for at home. For ninety years all these industrial, intellectual and social elements, fusing into an active and high-spirited community, were led and guided by able and patriotic men, now no more.

In fancy I can see them ranged around me in a noble historic gallery—Colonel Barclay and Isaac Wilkins, Sampson Salter Blowers, Foster Hutchinson, and many others. Was there one among them all who would have sold his country? Coming down to a later period, we find men of whom we are not ashamed. We are sometimes told that small countries produce small men, but John Young, Robie, Fairbanks, Bliss, Doyle, Huntington, Uniacke, Bell, in breadth of view, brilliancy and knowledge were the equals of the best that Canada ever produced. Which of these men would have sold Nova Scotia, or delivered her over, bound hand and foot, without the consent of her people to the government of strangers? There is not one whose picture would not start from the wall, whose bones would not rattle in the grave, at the very suspicion.

Sir, there is one name, that of S. G. W. Archibald, that among this fine fraternity is invested with a rare lustre in comparison with the recent achievement of one who has earned unenviable notoriety. When the rights and powers of our Parliament were menaced he defended them, and even though the immediate matter in dispute was but 4d. a gallon upon brandy, like the ship-money of old, it involved a principle, and Archibald defended the rights of the House, and the independent action in all matters of revenue and supply of the people of Nova Scotia. Gratefully is the act remembered, and now that we have seen all our revenues and the united power of taxation transferred to strangers, is it surprising that we should wish that the person who has perpetrated this outrage should have found another name?

The old men who sit around me, and the men of middle age who hear my voice, know that thirty years ago we engaged in a series of struggles which the growth of population, wealth and intelligence rendered inevitable. For what did we contend? Chiefly for the right of self-government. We won it from Downing Street after many a manly struggle, and we exercised and never abused it for a quarter of a century. Where is it now? Gone from us, and certain persons in Canada are now to exercise over us powers more arbitrary and excessive than any the Colonial Secretaries ever claimed. Our Executive and Legislative Councillors were formerly selected in Downing Street. For more than twenty years we have appointed them ourselves. But the right has been bartered away by those who have betrayed us, and now we must be content with those our Canadian masters give. The batch already announced shows the principles which are to govern the selection.

For many years the Colonial Secretary dispensed our casual and territorial revenues. The sum rarely exceeded £12,000 sterling, but the money was ours, and yielding at last to common sense and rational argument, our claims were allowed. But what do we see now? Almost all our revenues—not twelve thousand but hundreds of thousands—are to be swept away and handed over to the custody and the administration of strangers.

The old men here remember when we had no control over our trade, and when Halifax was the only free port. By slow degrees we pressed for a better system, till, under the enlightened commercial policy of England, we were left untrammelled to levy what duties we pleased and to regulate our trade. Its marvellous development under our independent action astonishes ourselves, and is the wonder of strangers.

We have fifty seaports carrying on foreign trade. Our shipyards are full of life and our flag floats on every sea. All this is changed: we can regulate our own trade no longer. We must submit to the dictation of those who live above the tide, and who will know little of and care less for our interests or our experience.

The right of self-taxation, the power of the purse, is in every country the true security for freedom. We had it. It is gone, and the Canadians have been invested by this precious batch of worthies, who are now seeking your suffrages, with the right to strip us “by any and every mode or system of taxation.”

We struggled for years for the control of our Post Office. At that time rates were high, the system contracted; offices had only been established in the shire towns and in the more populous settlements. We gained the control, the rates were lowered and rendered uniform over the Provinces, newspapers were carried free, offices were established in all the thriving settlements and way offices on every road, but now all this comes to an end. Our Post Offices are to be regulated by a distant authority. Every post-master and every way office keeper is to be appointed and controlled by the Canadians.

Since the necessity for a better organization of the militia became apparent, our young men have shown a laudable spirit of emulation and have volunteered cheerfully, formed naval brigades, and shown a desire to acquire discipline and the use of arms. I have viewed these efforts with special interest. There is no period in the history of England when the great body of the people were better fed, better treated, or enjoyed more of the substantial comforts of life, than when every man was trained to the use of arms, and had his long-bow or his cross-bow in his house.

The rifle is the modern weapon, and our people have not been slow to learn the use of it. Organized by their own Government, commanded by their friends and neighbours, 50,000 men have been embodied and partially drilled for self-defence. But now strangers are to control this force—to appoint the officers and to direct its movements; and while our own shores may be undefended, the artillery company that trains upon the hills before us may be ordered away to any point of the Canadian frontier.

By the precious instrument by which we are hereafter to be bound, the Canadians are to fix the “salaries” of our principal public officers. We are to pay, but they can fix the amount, and who doubts but that our money will be squandered to reward the traitors who have betrayed us? Our “navigation and shipping” pass from our control, and the Canadians, who have not one ship to our three, are already boasting that they are the third maritime power in the world. Our “sea-coast and inland fisheries” are no longer ours. The shore fisheries have been handed over to the Yankees, and the Canadians can sell or lease tomorrow the fisheries of the Margaree, the Musquodoboit or the La Have.

Our “currency,” also, is to be regulated by the Canadians, and how they will regulate it we shrewdly suspect. Many of us remember when Nova Scotia was flooded with irresponsible paper, and have not forgotten the commercial crisis that ensued. In one summer thousands of people fled from the country, half the shops in Water Street, Halifax, were closed, and the grass almost grew in the Market Square. The paper was driven in. The banks were restricted to five-pound notes. All paper, under severe penalties, was made convertible. British coins were adopted as the standard of value, and silver has been ever since paid from hand to hand in all the smaller transactions of life.

For a quarter of a century we have had free trade in banking, and the soundest currency in the world. Last spring Mr. Galt could not meet the obligations of Canada, and he could only borrow money at ruinous rates of interest. He seized upon the circulation, and partially adopted the greenback system of the United States. The country is now flooded with paper; only, if I am rightly informed, convertible in two places—Toronto and Montreal. The system will soon be extended to Nova Scotia, and the country will presently be flooded with “shin-plasters,” and the sound specie currency we now use will be driven out.

Our “savings banks” are also to be handed over. Hitherto the confidence of the people in these banks has been universal. We had the security of our own Government, watched by our own vigilance, and controlled by our own votes, for the sacred care of deposits. What are we to have now? Nobody knows, but we do know that the savings of the poor and the industrious are to be handed over to the Canadians. They also are to regulate the interest of money. The usury laws have never been repealed in Nova Scotia, and yet capital could always be commanded here at six, and often at five per cent. In Canada the rate of interest ranges from eight to ten per cent, and is often much higher. With confederation will come these higher rates of interest, grinding the faces of the poor.

But it is said, why should we complain? we are still to manage our local affairs. I have shown you that self-government, in all that gives dignity and – security to a free state, is to be swept away. The Canadians are to appoint our governors, judges and senators. They are to “tax us by any and every mode” and spend the money. They are to regulate our trade, control our Post Offices, command the militia, fix the salaries, do what they like with our shipping and navigation, with our sea-coast and river fisheries, regulate the currency and the rate of interest, and seize upon our savings banks.

What remains? Listen, and be comforted. You are to have the privilege of “imposing direct taxation, within the Province, in order to the raising of revenue for Provincial purposes.” Why do you not go down on your knees and be thankful for this crowning mercy when fifty per cent has been added to your ad valorem duties, and the money has been all swept away to dig canals or fortify Montreal. You are to be kindly permitted to keep up your spirits and internal improvements by direct taxation.

Who does not remember, some years ago, when I proposed to pledge the public revenues of the Province to build our railroads, how Tupper went screaming all over the Province that we should be ruined by the expenditure, and that “direct taxation” would be the result. He threw me out of my seat in Cumberland by this and other unprincipled war-cries. Well, the roads have been built, and not only were we never compelled to resort to direct taxation, but so great has been the prosperity resulting from those public works that, with the lowest tariff in the world, we have trebled our revenue in ten years, and with a hundred and fifty miles of railroad completed, and nearly as much more under contract, we have had an overflowing treasury, and money enough to meet all our obligations, without having been compelled, like the Canadians, to borrow money at eight per cent, and to manufacture greenbacks.

But if we had been compelled to pay direct taxes for a few years to create a railroad system that by-and-by would be self-sustaining, and that would have been a great blessing in the meantime, the object would have been worth the sacrifice. But we never paid a farthing. What then? The falsehood did its work. Tupper won the seat, and now, after giving our railroads away, and all our general revenues besides, the doctor, after being rejected by Halifax, is trying to make the people of Cumberland believe that to pay “direct taxes” for all sorts of services is a pleasant and profitable pastime. Cumberland may believe and trust him again, but if it does, the people are not so shrewd or so patriotic as I think they are.

But listen, you have another great privilege. What do you think it is? You are allowed “to borrow money.” But will anybody lend it? Most people find that they can borrow money easiest when they do not want it, but where is it to be got? The general government, who can tax you “by any and every mode,” and override your legislation as they please, have also power to borrow. If I know anything of the men who now rule the roost in Canada, they will screw every dollar out of you that you are able to pay, and borrow while there is a pound to be raised at home or abroad. Thus fleeced, and with the credit of the Dominion thus exhausted, who will lend you a sixpence should you happen to want it? Nobody who is not a fool. There is not a delegate among the lot who would lend £100 upon such security.

But you have other great privileges. Listen again. You are generously permitted to maintain “the poor,” and to provide for your “hospitals, prisons and lunatic asylums.” We have it on divine authority that the poor “will be always with us,” and come what may we must provide for them. What I fear is that, under confederation, the number will be largely increased, and that when the country is taxed and drained of its circulation, the rich will be poorer and the industrious classes severely straitened. The lunatic asylum of course we must keep up, because Archibald may want it by-and-by to put Tupper and Henry into at the close of the elections.

Keep cool, my friends. This precious instrument confers upon you other high powers and privileges. You are permitted to establish local courts, and to “fine and imprison” each other. And this brings me to the key to this whole “mystery of iniquity.” Local courts you may establish. The Supreme Court is to be transferred to the general government, which is to appoint the judges and fix the salaries. Our judges now receive £700 or £800 currency per annum. The judges in Canada get £1000 or £1250 currency. The delegation which represented Nova Scotia in Canada and England was composed of five lawyers and a doctor. What the doctor is to get we may see by-and-by, but the five lawyers expect to be judges. John A. Macdonald knew this very well, and when he opened his confederation mouse-trap he did not bait it with toasted cheese. Judgeships, with these high salaries, was the bait that he dangled before their noses. They were caught, and though they hated each other, and had spoken a good deal of severe truth of each other before they went to Quebec, the bait produced a marvellous effect upon them, and, like a happy family, they have lived in brotherly love ever since, wagging their tails just whenever Mr. Macdonald told them.

But this bait was intended to have effect outside the mere delegation—to influence judges and lawyers in all the provinces. The confederates tell us that in this Province all the judges and lawyers are in favour of this scheme. If it were so, we should perhaps not be much surprised. All the carpenters would be in favour of it if you could convince them that their wages would be doubled. Let us hope that this assertion is but a scandal.

The bar, certainly, is not all in favour of the scheme. Many high-spirited men in the profession loathe the very name of confederation. As respects the judges, whatever may be their opinions, let us hope that they have never expressed them. Among the other inestimable blessings which we have had in Nova Scotia has been a pure administration of justice—a spotless ermine, worn by men above suspicion of political bias or corruption. Let us hope that this distinction may be ours while our old constitution lasts. “Shadows, clouds and darkness” rest upon the future, and nobody can tell what we are to have next.

Hitherto we have been a self-governed and independent community, our allegiance to the Queen, who rarely vetoed a law, being the only restraint upon our action. We appointed every officer but the Governor. How were the 1867 high powers exercised? Less than a century and a quarter ago, the moose and the bear roamed unmolested where we stand. Within that time the country has been cleared—society organized. The Province has been intersected with free roads—the streams have been bridged—the coasts lighted— the people educated, and all the modern facilities afforded by cheap postage, telegraphs, and railroads were rapidly being brought to every man’s door, and the growth of our mercantile marine evinced the enterprise and indomitable spirit of the people. A few years since there were eleven “captain cards” upon the Noel shore.

Some time ago I went into a house in the township of Yarmouth. There was a frame hanging over the mantelpiece with seven photographs in it. “Who are these?” I asked, and the matron replied, smiling, “These are my seven sailor boys.” “But these are not boys, they are stout powerful men, Mrs. Hatfield.” “Yes,” said the mother, with the faintest possible exhibition of maternal pride, “they all command fine ships, and have all been round Cape Horn.” It is thus that our country grew and throve while we governed it ourselves, and the spirit of adventure and of self-reliance was admirable. But now, “with bated breath and whispering humbleness,” we are told to acknowledge our masters, and, if we wish to ensure their favour, we must elect the very scamps by whom we have been betrayed and sold.

But we are told that we ought to be reconciled to all this because we are to have the Intercolonial Railroad, and because, financially, the delegates have made so good a bargain. If you will bear with me a few moments I will dissipate this delusion. I am speaking from memory, and my figures may not be strictly accurate. But in the main they will be found correct, and the argument based upon them is irresistible.

When I went into the Legislature in 1837 our revenue was about £60,000. It only doubled in seventeen years, before we commenced building our railroads. In 1854 we passed our railroad laws, and in 1855 Tupper went screaming all over Cumberland, prophesying ruin and decay. In ten years since then our revenues have trebled, and last year amounted to £400,000. We have built the road to Truro, the road to Windsor, the extension to Pictou; and before this precious bargain and sale of all our resources was consummated we had the Northern road to New Brunswick, all of the Intercolonial within our borders, and the road to Annapolis under contract.

We had money enough to pay for all these roads without being under any compliment to the Canadians or the British Government either; and in ten years more, without financial embarrassment, could have extended our system to Yarmouth on the one side, and to Sydney on the other. At this moment it was—with my railroad policy so successful—the country, that Tupper swore I had ruined, so prosperous—the treasury, which he declared was milked dry, overflowing year by year, under the tariff we bequeathed to him, and our debentures two or three per cent above the bonds of Canada—that we were sold like sheep. This was the moment for these delegates to step in and trade us away, our rights and revenues, to Canada. God help us, and enable us “to possess our souls in patience.” No such deed as this was ever done or attempted where death was not the penalty.

I cannot help smiling when I hear Tupper crowing about the railroads he has built. He ought to be ashamed of vain boasting. We all know, and he knows, that had his warning voice been heeded, there never would have been a mile of railroad built in Nova Scotia up to this hour. The roads to Windsor and to Truro were built upon the policy inaugurated by myself, and with the money borrowed by me in England. What had he to do with it? Just this— that the Government having changed, he and his colleagues paid away about £40,000 of your money to a parcel of contractors who set up irregular claims. All the roads made since have been made on my policy of pledging the public credit to make them, which Tupper declared would be ruinous. There has been, however, an important difference in the mode of dealing with contracts and expending the money, which ought to be held up to indignant reprobation.

When I was at the head of the Railway Board I was surrounded by six business men, an accountant, and an engineer. Every mile of road was thrown open to competition by tender and contract. When tenders were sent in they were placed in custody of the accountant till the time expired, and the whole board assembled. I never looked at one of them till they were opened in presence of all the commissioners, the accountant, and engineer. The lowest tender, if the party produced good security, took the contract, without reference to politics, to country, or to creed. Look at the new system inaugurated by Dr. Tupper. Take the Pictou line as an illustration. A number of our own people tendered for the work. If kindly treated, some of them might have pulled through. If they did not, their bondsmen were liable. By a system of dealing, instead of the work being put up to tender again, the whole was handed over to the engineer by private bargain, a system most unfair to the whole people, and open to suspicion of gross favouritism and corruption. Instead of offering the northern and western lines to fair competition, the Government took powers to hand them over, by private bargain, to whomever they chose to select. I do not say, because I cannot prove, that any of the members of the Government were sleeping partners, or profited by these contracts. But I do say that the system was most perilous to the public interests, and open to grave objections. We pray to be “kept out of temptation,” but these gentlemen, with profitable contracts to dispose of, amounting to nearly a million and a half of money, exposed themselves to temptations hard to resist, and laid themselves open to suspicions widely entertained. I left the Railway Board as poor as I went into it. I bought or built no property then or since. I hope those who succeeded to the administration have left with hands as clean.

Let me turn your attention, now, to the bargain that has been made with Canada. We give them the roads already completed, which have cost nearly a million and a half. We give them the roads under contract, which may cost another million. We give them revenue enough to cover the interest upon these roads, till they pay, when they will get them for nothing, and have the revenue besides. Our whole revenue now amounts to £400,000. It has trebled in ten years. If it only doubles in the next ten we will have £800,000. By that time our old roads will pay, and the new ones yield half the interest. Out of this sum we are to get back of our own money £133,000, a sum utterly inadequate to provide for Provincial services now, and by that time deplorably insufficient. We can only provide for those services by direct taxation. The Canadians get all the rest.

Hitherto I have reasoned upon a ten per cent. tariff, which would have provided for all our wants, and given a fund for railway extension to the extremities of the Province, east and west. But we know that under confederation our tariff will be raised to fifteen per cent. If the revenue is collected, taking our Customs duties at $1,231,902, the additional taxation will take out of our pockets $500,000 the very first year. The interest on the £3,000,000 required for the Intercolonial road is £120,000 sterling. The road will take four years to construct. The Canadians will only pay interest as the work goes on, yet from the start they will take out of our pockets by increased duties, to say nothing of the general revenues surrendered, £100,000 sterling, a sum nearly sufficient to pay the interest on the whole three millions. This is the profitable bargain they have made, and they have the audacity to suppose that Nova Scotians are such idiots that they can cover up the transaction with every species of falsehood and mystification. They shall not do this. It shall be presented to the people everywhere in its naked deformity and injustice, and when it is they will pronounce universal condemnation. You have been told that Mr. Annand, Mr. McDonald, and I opposed the Intercolonial Railroad. Why, if the bargain had been a good one, we would have flung the road to the winds to save the independence of the Province, but being what it is, a fraud upon the revenues and an insult to the common sense of Nova Scotia, we did our best to defeat it.

But confederation will bring with it other blessings. Stamp duties, hitherto unknown, will soon be imposed, and toll-bars will become ornaments of the scenery. We have but two toll bridges in the Province, and all our roads are free. In Canada you can hardly travel five miles without being stopped by a toll-bar, and compelled to pay for the use of the road. Our newspapers now go free, but they will soon be taxed as they are in Canada. For all these mercies should we not be thankful to the delegates? Yes, as thankful as men are for the plague or the smallpox.

But we are told when we complain of this fraudulent conveyance of our independence—of this reckless sacrifice of our dearest interests, that we are disloyal—that we are annexationists, Fenians, and dangerous persons. Are we indeed?

A year ago there was no annexationist in Nova Scotia. If there are any now, we have to thank those who have overthrown our institutions, and treated the population with contempt. This old cry of disloyalty does not terrify me. It has been raised by some interested faction at every crisis of our Provincial history. I met it at the outset of my public life, and trampled the accusation under my feet in the old trial with the magistrates of Halifax. I met it again at the outbreak of the Canadian rebellion, and put the enemy to shame by the publication of my letter to Chapman. The records are here, and he who runs may read.

[Holding up a volume of speeches.] Surrounded by the élite of Massachusetts, all the Yankees eminent in station and distinguished by talent, I have vindicated the institutions and upheld the honour of Great Britain. You know—these wretched slanderers know—how at Detroit, before the commercial representatives of the Provinces and of the Northern States, I won the respect of our neighbours by the triumphant vindication of British interests; and won what, perhaps, I valued as much, the thanks of my Sovereign, conveyed to me by the Secretary of State. But Dr. Tupper accuses me of disloyalty, does he, and sets his newspapers, subsidized with public plunder, to asperse better men than himself?

Let me contrast his conduct with my own. During the Crimean war our army was decimated by the great battles of the Alma, Balaclava and Inkerman. Surrounded by hordes of Russians, and suffering for supplies, there was some risk that they might be driven into the sea. Reinforcements were urgently required, and a Foreign Enlistment Act was passed. To assist in carrying out that Act I risked my life for two months in the United States, surrounded by Russian agents, American sympathisers, and Fenians. Mr. Gibson, now in this room, was in New York at the time, and knew the state of feeling, and urged me to quit the service and not risk imprisonment or personal violence. I persevered, rarely sleeping twice in the same bed till recalled; and this I did for England in her hour of peril, and never received a pound for my services, or asked one.”

Now, what was Dr. Tupper doing at this time? He was scouring the county of Cumberland while I was absent on the service of the Crown, meanly endeavouring to deprive me of my seat. He slandered me in every part of the county—he invented stories that I was imprisoned and would not be back. I only got back a few days before the election, too late for any canvass or efficient organization, and was defeated, of course. In this dishonourable mode he won the seat he now holds, and certainly illustrated his devotion to his Sovereign after a mode that ought to be remembered. At a later period, in 1862, when, foreseeing the dangers which have since threatened these Provinces, my Government revived the militia law and increased the annual grant for defence, did not this very loyal gentleman endeavour to reduce the Governor’s salary, to deprive him of the vote for a secretary, and to strike out $8000 of the grant for the militia upon the ground that the Province was so poor that it could not afford the expense?

I pass by this “retrenchment scheme” as utterly beneath contempt. I pass by the wretched jobs by which his administration has been distinguished – from its commencement to its close. Let me waste a few words on the cry that “we ought to send the best men”—by which, of course, these precious delegates mean themselves. The best men of this lot, bad is the best. Now the best men to send are not scheming lawyers, who would dig up and sell their fathers’ bones for money or preferment, but honest men in whom the people of this country have entire confidence. Dr. Tupper has already chosen his twelve senators, and now he wants to be allowed to choose the people’s representatives. Why should he not? You were too stupid to pass an opinion upon confederation. Are you sure that you have sense enough to choose a representative?

The “best men”!—let us see how he has chosen. In the first place he has taken six senators from one county, leaving eleven counties entirely unrepresented. Then he has taken three men who were open and avowed anti-confederates; who ratted, sold themselves, and were purchased by the distinction. A friend came in and told me last spring that he was afraid Bill was being tampered with, as he saw Tupper taking him up to Government House that morning. I discredited the story, because I did not believe that the Queen’s representative would degrade his office by canvassing and tampering with members of the House. I think so still. No doubt the visit was one of mere form, but Caleb’s name appears in the list of Ottawa senators, and who doubts how his sudden conversion was effected? Compare him with McHeffy, who is in gentlemanly manners, intelligence and sturdy independence, out of sight his superior. Yet the best man is left behind because he would not sell his country. Who does not remember Miller denouncing the confederation scheme on the platform in Temperance Hall, and there and everywhere declaring that it ought to be sent to the hustings. But he was a convert, and the price must be paid, even though Mather Almon, who in experience and weight of character was his superior in every quality required for a legislator, should be left behind.

Of the candidates who have presented themselves for the representation of this county on the other side, it is enough to say that they are on that side, and are not the men for Galway. I would vote against my own brother if he had a hand in these transactions, or if he attempted to justify the mode in which the people of Nova Scotia have been treated. The very life and soul of any country are honour and good faith. We can never hold up our heads till we stamp out treachery, as we would the rinderpest if it came here. We would not let a plague spread among our cattle, and we must not allow our people to be contaminated with the example of these delegates. Such treason as theirs, in other countries, would earn for them the halter or axe. We may not even elevate them to the dignity of tar and feathers, but we can at least leave them on the stools of repentance to become wiser and better men.

Of the people’s candidates I need say but little. They are known to you all, as industrious, honest, business men, of shrewdness and intelligence. Mr. Cochrane and Mr. Power are universally respected by the body to which they belong, and enjoy the confidence of the community. Mr. Jones and Mr. Northup are men to whom you can safely entrust your interests at home and abroad. Mr. Balcom I have known for twenty years. I have slept beneath his roof, and know that in his domestic relations and in his commercial activity he is a fitting representative of the sturdy class of men who are enlivening the sea-coast by their industry. None of these men care for public distinctions. They would retire tomorrow, if by so doing they could serve their country. They can serve her best by fighting her battles out, and I hope to see the whole five triumphantly returned.

Howe, Joseph. Annand, William. Chisholm, Joseph Andrew. “The Speeches and Public Letters of Joseph Howe” Halifax, Canada: The Chronicle publishing company, 1909. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007688708

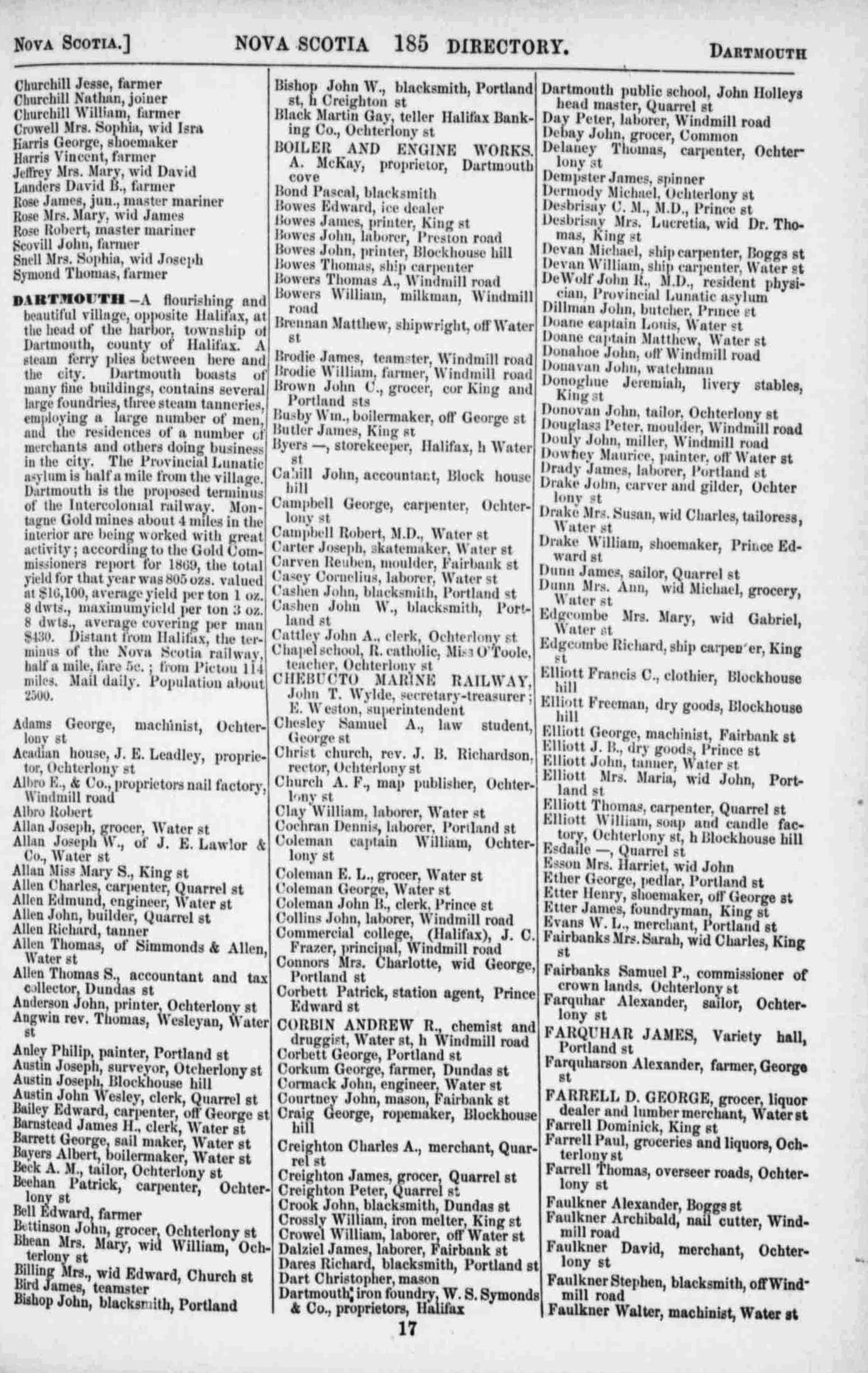

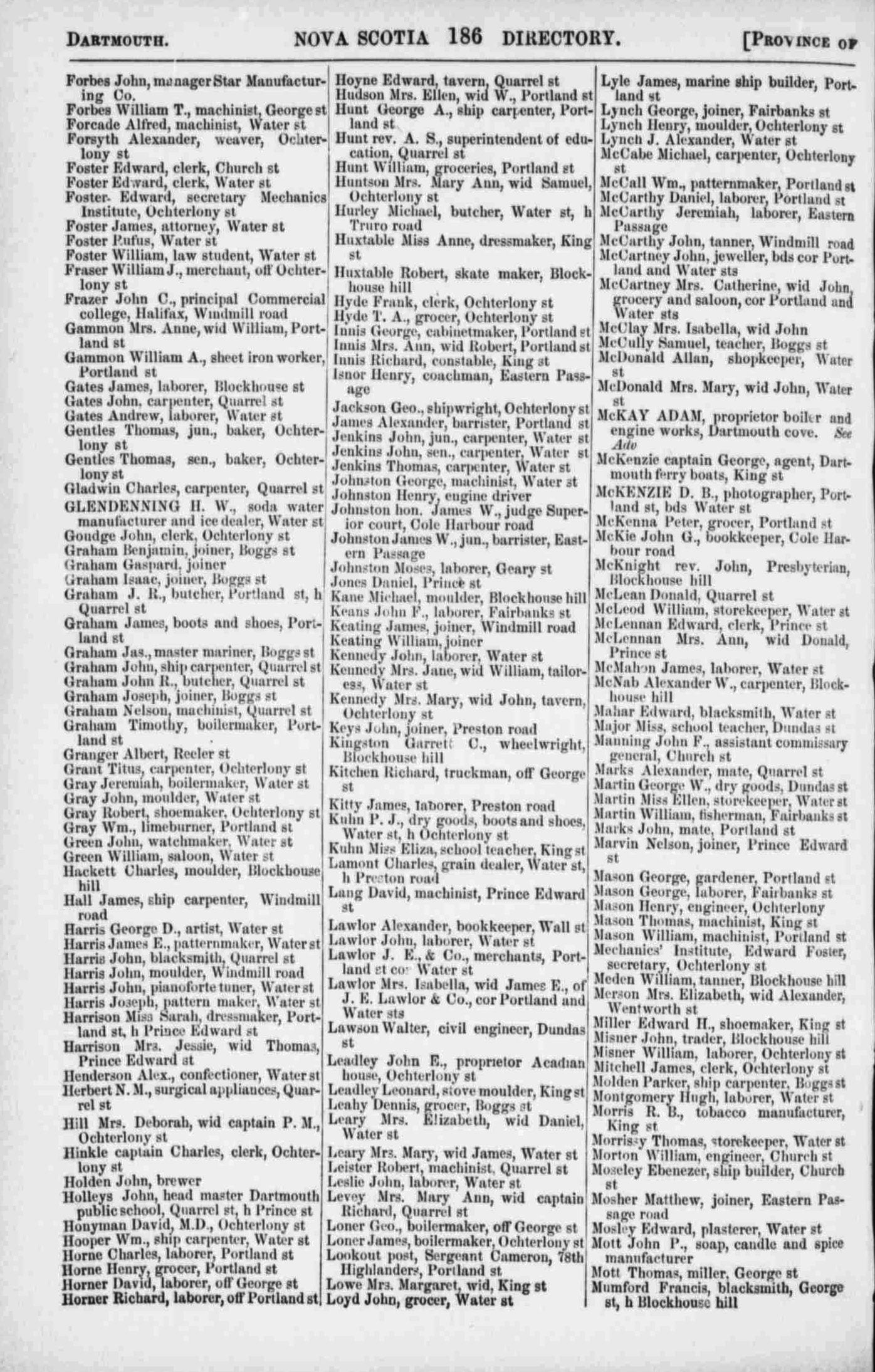

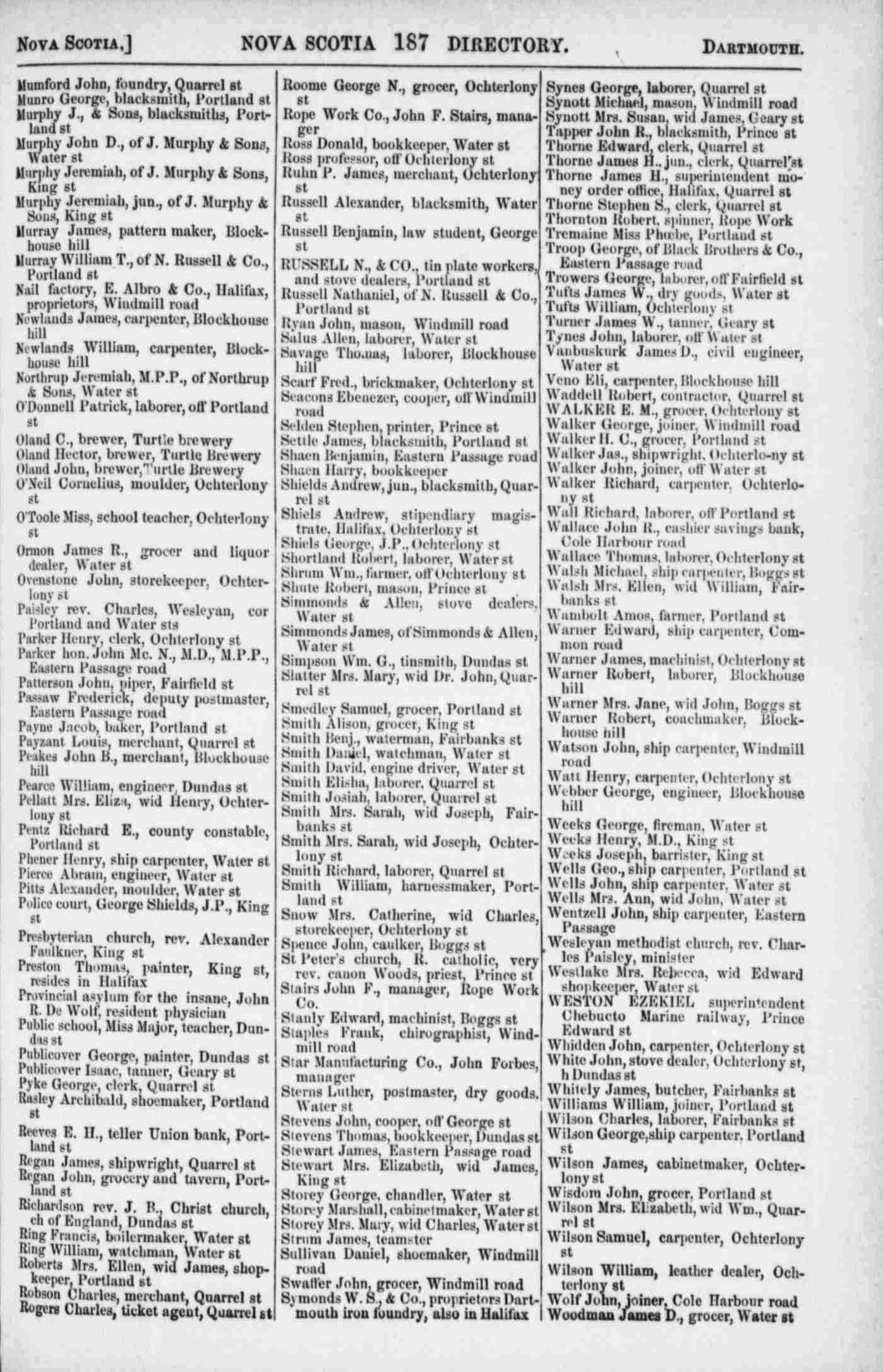

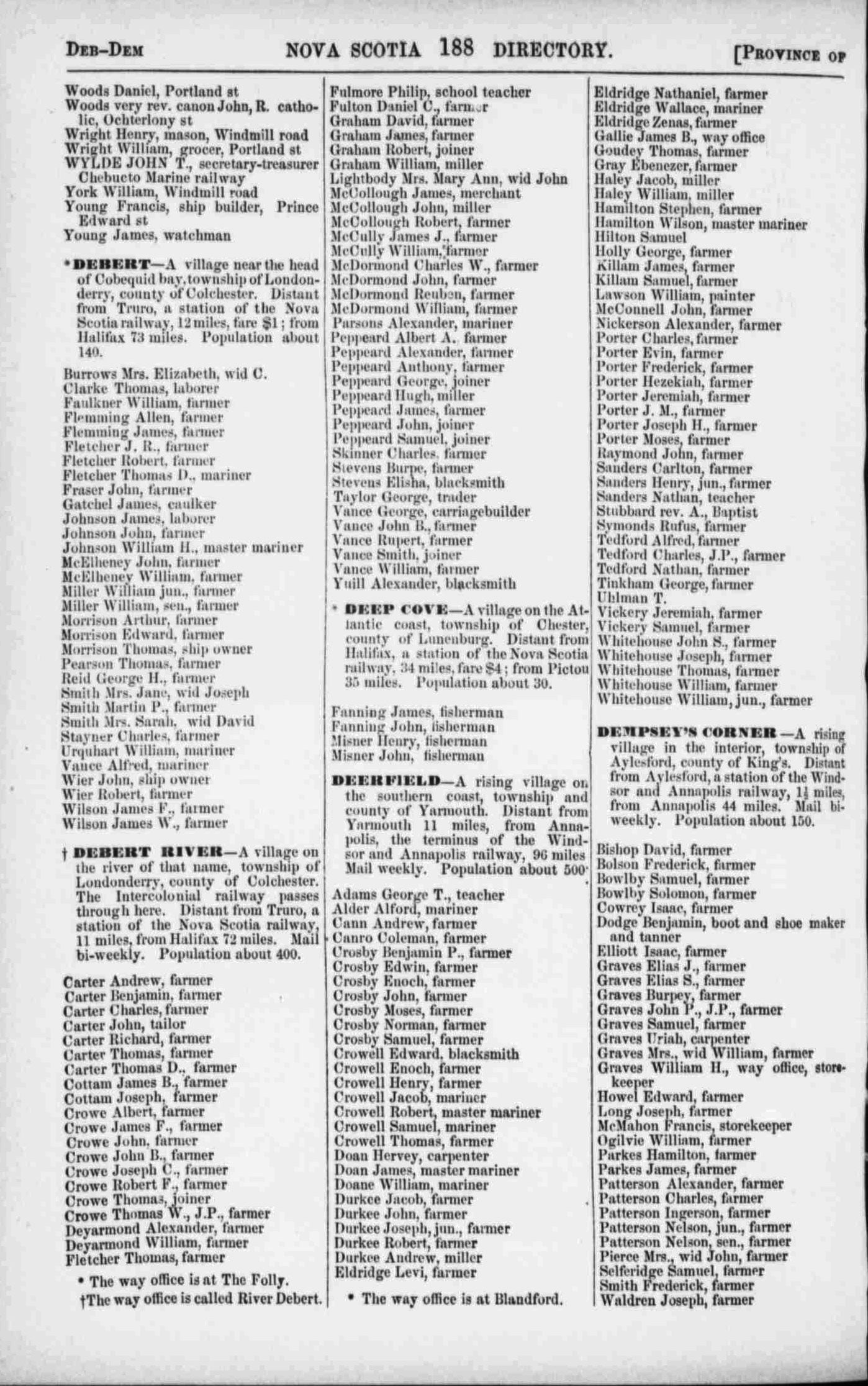

Lovell’s Province of Nova Scotia directory for 1871

“Dartmouth – A flourishing and beautiful village, opposite Halifax, at the head of the harbor, township of Dartmouth, county of Halifax. A steam ferry plies between here and the city. Dartmouth boasts of many fine buildings, contains several large foundries, three steam tanneries, employing a large number of men, and the residences of a number of merchants and others doing business in the city. The Provincial Lunatic asylum is half a mile from the village. Dartmouth is the proposed terminus of the Intercolonial railway. Montague Gold mines about 4 miles in the interior are being worked with great activity; according to the Gold Commissioners report for 1869, the total yield for that year was 805 ozs, valued at $16,100, average yield per ton 1 oz. 9 dwts., maximum yield per ton 3 oz. 9 dwts., average covering per man $430. Distant from Halifax, the terminus of the Nova Scotia railway, half a mile, fare 5c.; from Pictou 114 miles. Mail daily. Population about 2500.”

Lovell’s Province of Nova Scotia directory for 1871, Montreal : Printed and Published by John Lovell, [1871?] https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_00107_1

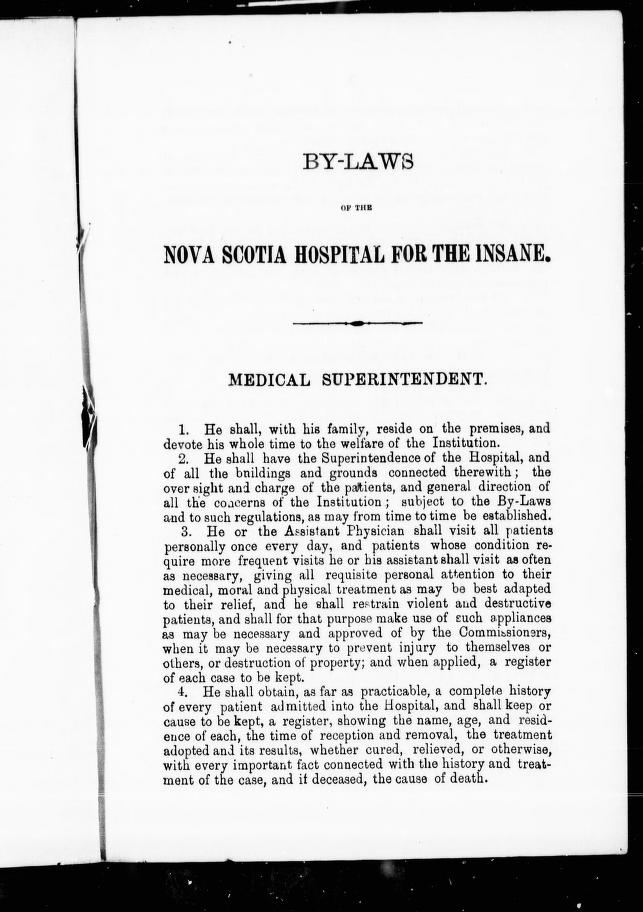

By-laws of the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane, Mount Hope, Dartmouth, 1877

“Obligations: To be signed in the presence of the Superintendent by each attendant and servant , before appointment.

I hereby promise to obey the bye-laws and rules of the Hospital, to be careful of its property, and to avoid gossiping about its inmates or affairs. I consider myself bound to perform any duties assigned to me by the Superintendent, or assistant physician.

I understand my engagement to be monthly, and I agree to give a months notice in writing, should I wish to leave my situation.

If anything contrary to the rules of the Hospital, be done in my presence, or come within my knowledge, I pledge myself to report it to the Medical Superintendent or Assistant Physician and to the Commissioner for the Hospital.

I acknowledge the right of the Commissioner of Public Works and Mines to discharge me without warning, for acts of harshness or violence to the patients, for intemperance, or disobedience of orders.”

Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane. “By-laws of the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane, Mount Hope, Dartmouth”, Signed and dated: P. C. Hill, clerk of council, January 19, 1877. https://archive.org/details/cihm_58569/page/n5/mode/2up

Stirpiculture, or, The ascent of man

“…any favoured trait can be developed by the proper study of heredity.”

“The human family is composed of four classes:

- The Good, Those who are actuated by high resolves, no matter what their position or associations may be.

- The Bad, Who are quite intractable

- The irresponsibles, Insane and idiotic

- The great bulk of humanity that is moulded by and are the creatures of association and training.

The first does not need our attention. The second are ulcerous and diseased outgrowths on society that will pass away and our efforts must be directed to prevent future recurrence. The third, a gradually increasing class, the result of natural causes, and if not to be eliminated in toto could be greatly reduced in numbers. The fourth class is the one that all efforts of society should be directed towards perfecting, for from it the preceding classes spring, and but few laws need to be studied or acted upon. They are:

- Hereditary transmission

- Indissolubility of the marriage tie with its home associations

- A correct appreciation of the dignity of labour, and that all individuals be trained to make their own living by the hand as well as the head.

- Moral training with fixed or positive religious ideas.

- A general and practical education

- Definite instruction in sanitary laws.”

“We have about 1,500 to 2,000 insane in our province … a very large percentage of whom are immured in asylums, many for a great part and more for the whole of their active lives, at a very large and increasing cost to the communities. These people are nearly all dependent on state aid, but the impoverished condition of them and their dependents is due to their affliction. In looking over the histories of the 2400 admissions to our own asylum, I could not find one who had not been self-supporting before his or her affliction.

…there is no vivid consciousness that men and women of every grade of society, except the paupers and criminals, are immured in what to them is a prison, and all civil rights and personal freedom denied them, and as far as they can see, for no just cause. They never did any injury (except now and then in self-defense from their point of view) and have not even the melancholy pleasure enjoyed by the criminals of at least knowing how long their liberties are to be restrained and the cause for their incarceration. They were simply honest in expressing their opinions and these did not coincide with those prevailing in the community.”

“From one tainted emigrant to this province there has been a thousand crippled intellects”

“A rule that was once general and still obtains at the Imperial Palace, at Berlin, that every young man should be proficient in some handicraft and every woman in the practical details of household work, has, unfortunately, been falling into abeyance; more so in America than in Europe.”

“…it stands to reason that if Jack were as good as his master he would occupy that position.”

“…the subject of Stirpiculture, the perfection of our race, is a grand one and deserves more care and study than it has thus received”

Reid, A. P. “Stirpiculture, or, The ascent of man”, N.S. Institute of Natural Science, 1890. https://archive.org/details/cihm_13074

Supplementary evidence as to the management of the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane, Mount Hope, Dartmouth

I, James S. Wilson, of the City of Halifax, make oath and say as follows : —

I was engaged as an assistant, and afterwards as an attendant at the Provincial Hospital for the Insane. I was employed there about fifteen months, and left there the 9th December last. I was employed in all the Male Wards, except M 7.

The food was frequently very inferior, the butter rancid, and at times more like lard than butter. In some of the Wards, there was none given to the patients, the attendants had only enough for themselves. The bread was occasionally sour. There were four or five barrels flour which I saw in the bakery, which was sour, about the months of July and August. The baker called my attention to it, and said, ”that he could make bread almost out of saw-dust, but that he could not make good bread out of that flour.” The meat was often very poor; I remember well on one or two occasions when the corned beef was so tainted that it could not be eaten. The milk was frequently sour, with the cream taken off it. I saw butter-making going on in the kitchen. The molasses was often sour, and very dark, and the sugar the color of molasses sugar. The fish occasionally was not sound, and had a bad smell.

Wet beds were permitted to remain so for days on which the patients slept at night. The practice in the Hospital was, in Summer, when the weather was fine, to put the beds out sometimes, just as they were, to dry in the sun, and in the Winter time, occasionally to take them in the same state to the hot air chamber below. The beds have often been allowed to remain in a wet state for several days together. I never saw the Male Supervisor examine a bed after it was made up; he passed through mostly like any other visitor. I never saw Dr. DeWolf examine a bed but once. Mr. McNab was in the habit of giving notice to the attendants when the Commissioners were coming, to get the outside quilt on, and any of the rooms not in a good state, to lock them up. There was an insufficiency of bed- clothes, particularly sheets ; and a great cause of the wet beds was the want of bed-sacks. I had to wait about three months before I could get half-a-dozen sacks, which I had applied for. I found several of the patients lousy when I entered the Wards, and there was not sufficient clothing to change them with, so as to keep them clean. I had to put the clothing in salt and water in the bath tub to destroy the vermin. Mr. McNab stated they were complaining in the laundry about sending too many clothes to the wash. In the Ward which I had charge of, there were twenty-five patients and two attendants. We had often to wash some of our own clothes in the Ward. We had some very dirty patients ; and as well as I can recollect, there was an aver- age of not more than eight sheets a week sent to the wash. About every three weeks a bed had one sheet put on it.

The air in the Wards was at times very bad; the registers of the hot air flues were some of them off altogether, and others broken. The patients would often put food, human filth, and other rubbish down these flues. I have seen it cleaned out below. I made application to have those registers put on, and repaired, and spoke to the Medical Superintendent about it, but it was not attended to. There was no fire brigade organized, nor were the attendants ever shown how to put out a fire or how to use fire apparatus. I saw only one old piece of hose which was unfit for use, and the taps for fire purposes in the wards were never once turned or used while I was there. There were no wrenches to turn them with, and no spanners to couple a hose on.

Doctor DeWolf did not go through the wards daily, he was very irregular in his visits. At times, not often, he would visit the wards sometimes once a week, and at times not more than once in three weeks. Dr. Fraser was generally very regular in his visits, mostly daily. I have known patients confined to the dark room for over a week, and never seen by the Superintendent during that time; they were very violent patients, some of them were naked and their rooms were in a bad state. I know that Thyne and Hubley were afraid to go into the rooms, and they occasionally came to me to give them assistance.

Ward M 1 was frequently very cold in Winter, and not promptly attended to when complained of.

The idea generally among the attendants was, they had better for their own sakes make as few complaints as possible.

A man named Fayle was sick, and I was attending on him in M 2. I saw he was very low, and I sent for the doctor two or three times, but he was not to be found in the building. After some time, he came up from his daughter’s, but the man was dead. Dr. Fraser was in Halifax at the time.

I have seen the steward (Downie) under the influence of drink, frequently, with as much as he could carry.

I have seen Hon. Robert Robertson pass through the Wards occasionally, not often, sometimes with Mr. Dustan; neither ever examined a bed, raised even the bed clothes, turned one over, or out, while I was in the Ward. They could not have done so without my seeing them.

It was generally known and talked of in the institution, that the doctors were not on friendly terms.

[Sd.] JAMES S. WILSON.

Sworn at Halifax, N. S., this 12th day of July, A. D. 1877, before me, William Evans, J. P. }

Province of Nova Scotia, Halifax, S.S. }

I, Michael Meagher, of the City of Halifax, Yeoman, make oath, and say as follows : —

I say that I was an assistant attendant in M 8 Ward, in the Provincial Hospital for the Insane, from, or about the month of September, 1875, until May, 1876. I had constant opportunities of noticing the quality and quantity of the food used. The butter was often uneatable from being rancid; it had frequently to be sent back; it was sometimes two or three days before we got any in its place. The butter was always strong.

The tea was of poor quality, often very poor. The milk was hardly noticeable in the tea, the quantity was so scanty. In September, when I was first employed, the bread was sour and soggy. Afterwards, it got a little better.

Sometimes, the meat was insufficient, except for ten or twelve who worked outside There were from thirty to thirty-five persons in my Ward. Some days the patients got no meat, other times we showed them a sign of it, to prevent complaint. Other times we had to see which patient to take it from, in order to give it to another who would be more troublesome. One class of patients got butter, others none.

There were a number of wet beds daily in my Ward. They were rarely taken out in the air. They were generally left for some days as they were. One patient, Norman McNeil, was in a very bad state from bed-sores. He was paralyzed, and generally mute. I called Dr. Fraser’s attention to his state, so that I should not be under any responsibility about him. Nothing was done for him. Being nearly helpless, his bed was in a worse condition than other patients who could look after themselves. It was revolting to look at him. The sores were on his hips chiefly, and on his back. The bed-clothes were put out in the attic to dry, but it only hardened them; when the patient laid on them, the warmth and perspiration made them worse than ever. The bed-clothes of this patient were never taken to the laundry to wash, to my knowledge. I understood that they complained at the laundry, if we sent many clothes, especially if they were dirty. We sometimes washed them in the bath tub. It was the practice to leave the beds wet for days. There was not enough clothing to keep some of the patients warm in winter. There was not enough supplied to keep them clean. The clothes of some of the patients got full of lice. We had to soak the clothes in the bathtub to clean them of vermin.

Dr. De Wolf’s visits were irregular; he was absent from the ward generally from three to five days. His visits were generally what you call flying ones, except when he had friends with him, or the Commissioners. He never, to my knowledge, examined the patients medically, unless the attendants called his attention to a serious case. I have seen Dr. De Wolf, Dr. Fraser, Mr. McNab the Supervisor, the Commissioners and the Hon. Robert Robertson, going through the ward. I never saw them examine the beds turn them up, or turn them over. I was generally preset in my own ward, and would have seen them if they had done so. The Commissioners generally went through the corridor or sitting room. Seldom or never entered the patients’ rooms. Mr. McNab used to give us warning of the Commissioner’s visit, so as to make preparation for it. I know that Norman McNeil’s bed was in the condition I have described during some visits of the Commissioners. It was always in a bad condition, more or less. Mr. McNab was in the habit of walking through the ward like a casual visitor; he did not seem to examine anything as an official. From his conversation with me, I understood, on one occasion, that it would be better to let things go on quietly, and not make complaints. This was on an occasion when I called his attention to some deficiency.

I had no knowledge whatever of any fire organization, or appliances for extinguishing fire in the building. I saw one piece of old hose which was never used. I saw some taps, but there were no keys to turn them. There was no spanner to my knowledge. There were no fire buckets. Dr. DeWolfe and Dr. Fraser seldom or never visited the ward together. I saw them together only on two or three occasions. It was generally understood that they were not on good terms with each other.

A patient named Graham was in the dark room while I was at the Hospital. It was in the winter time. The glass was broken, and the rain came in and wet the floor. Graham was lying on the floor on a mattress. The room was in a very dirty condition. There was straw on the floor, and human excrements. I saw the snow not melted on the floor. We put the food in over the door sometimes. The doctor would occasionally enquire how he was. He never took a list of patients in that condition to my knowledge. He never went to see them. A man put in the dark room was entirely neglected. Graham was subject to fits; he might have died without assistance during the night; he was left entirely to his own resources after locking him up. Graham was a powerful muscular man. It was the practice of the attendants to give as little food as possible to patients in that state to reduce their strength; just enough food to sustain them. The doctors never enquired into the quantity of food given them. Graham was in the dark room from one to three weeks. The room was bitterly cold; it was hardly fit for a dog; it was not fit for a human being. I never saw McNab examine the bedclothes or other clothing while I was at the Hospital.

[Sd.] Michael Meagher

Sworn to at Halifax, this 3rd day of July, A.D., 1877, before me, William Evans, J.P.}

Lunatic Asylum, Mount Hope, 18th Sept 1873}

Rev. Sir, —

I take the liberty of addressing you, as I understand you were making enquiries last evening about injuries received by Abraham Landre whom you visited here, and I am in a position to give you some information. Landre, it seems, used to assist in the dining room in this ward, and about March last had some altercation with one Dyke, an attendant, who cruelly kicked and stamped upon him, inflicting the injuries, from the effects of which the unhappy man is now dying. Dyke, whose Christian name is Edwin, (but I am not quite sure, as some say it is Isaac), was afterwards discharged, but not for this matter, as the other patients were too much intimidated at the time to give evidence, though some inquiries were made. I, myself, was not here at the time, but there are tow convalescent patients, Charles Thompson and Benjamin King, who are still in the ward, witnessed the assault, and can give you all the particulars, should you require them. Edwin Dyke, I understand is a discharged soldier, and resides in Halifax.

I trust, Rev. sir, that you will not think me officious in making these matters known to you; but I, myself, have suffered so cruelly from brutal usage in this place that I wish, if possible, to save other poor creatures from similar treatment. I was brought here on the 7th June, and the next day, Sunday, I was brutally kicked and beaten; news of the outrage was leaked in my case, and three attendants, Wm. Robertson, W. Neil and Alex McCoy were discharged in consequence; but I do not think I shall ever completely recover from the injuries then received. My treatment has been good since that time. I have no personal animosity towards the Superintendant, Dr. DeWolf, whom I have always found courteous; but I have no hesitation in stating that he grossly neglects his duty of personal supervision and inquiry into individual cases, else such things as I have mentioned could never have happened. Several cases of ill-usage, though not quite the same extent, have come under my own eye. The secrecy which shrouds everything is also a very bad feature of the management here; friends are rarely allowed to see the patients, and visitors are only taken to wards kept in order for show, while others reek with filth and misery. I have been in this ward, containing about 30 patients, for three months and a lf, and you, Rev. Sir, are the only clergyman who has entered in that time.

You are quite at liberty to make any use of this letter you may deem fit, and I remain, Rev. Sir, Respectfully yours, Peter McNab. Rev. Mr. Woods &c,. &c.

I, Lida Hay, of Dartmouth, in the County of Halifax, make oath and say as follows : — I say that I was an assistant attendant in the N. S. Hospital for the Insane for about four months during the summer of last year. I had constant opportunities of seeing how some of the female patients were treated. I am acquainted with Miss Buree. She was the female night watch, and was usually engaged about half the day in what was called the infirmary ward. I have frequently heard her abuse and scold the invalid patients in the most violent manner. I saw her shake her fist in their face. I saw her prod the finger ends of a patient named Eliza Fanning in BBB ward with a pin, and heard the patient scream in consequence. I heard her threaten the patients that she would dip them. I did not at first understand what this meant, until I saw the operation performed. It is to tie a towel over the face, put the patient in the bathtub, head under water, until she would almost smother, and come out in a fainting condition. This dipping is not the usual bath taken by the patients every Friday; it is a special arrangement for punishing. I saw a very weak and infirm old lady named Mrs. Hassey, and said to have been in a convent formerly, forced through the corridor of the ward to the bath room in her bare feet, by Miss Buree, to undergo this process. She was dipped because she refused to eat. This patient was occasionally fed by Dr. Fraser with a stomach pump, and she died just before I left the Hospital.

From all that I have seen at Mount Hope, I would prefer that any relative or friend of mine would die rather than see them placed there.

Lida Hay

Sworn to at Dartmouth, this 4th day of Feb’y, A. D. 1878, before me, D. Farrell, J. P. Visiting Com’r. Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane.}

I, Kate Cameron, of Princeville, River Inhabitants, in the Island of Cape Breton, do solemnly declare — That I served as an attendant in the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane for about four years, that is, from 1874 until the 3rd December, 1877, under the management of Dr. DeWolf, and afterwards, from the 6th July, 1878, until January, 1879, under the management of Dr. Reid.

That there was a marked difference between the management under Dr. DeWolf and Dr. Reid.

That under Dr. Reid the patients were well attended to and regularly visited by him and his assistant, Dr. Sinclair ; that the patients had medicine and sick diet whenever necessary, and their wants in every respect provided for.

That under Dr. DeWolf the food was often unfit for use, and, when sent back, was told that it was good enough, and got no better. The meat I have seen rotten, and as a general thing the tea, butter and meat were bad. I have seen the bread often bad also.

That attention is now paid to the cleanliness of the patients. Formerly this was not the case, as the filthy condition of the beds was such that I have seen maggots crawling out of some of them.

That I have known patients to have been inhumanly treated and sadly neglected. The first act of cruelty which I remember was to an inoffensive woman named Elsie Turpel, from Granville, who was in the habit of tearing her clothes. She was stripped naked, her hands and feet tied, her hands behind her back, in a room, on a cold December night, in old F Ward, in 1874, without a bed. Next morning she was found dead, coiled up in the corner. I was called in to unbind her hands and feet. She had not been visited by the Superintendent or Assistant Physician until she was dead. There was no inquest ; the Doctor said she died of cramps.

That it was known to me that Mrs. McCoy, from Lake Ainslie, Cape Breton, was cruelly treated in No. 9 Ward. She was often put into the drying room, or closet, and cold water poured over her. One morning I heard that she would not eat her breakfast. I went down to see her and in about an hour after she died. She had a large cut in the back of her head. I heard that she was opened and that there was not a particle of food in her stomach.

That I had a patient named Bridget Dwyer locked in for about three months. Dr. DeWolf only saw her twice during that time, to my knowledge, and the Assistant Physician never once. Numbers of other cases of the same kind.

That a patient named Abbie Armstrong was sick for about five months. She suffered from diarrhea; nothing done for her, and no suitable nourishment. She died about a week after I left the ward. That another patient named Mary Walsh was also sick; she had sore toes for about three or four months, and was suffering with diarrhea ; she, too, had neither medicine nor nourishment of any consequence.

That I had to wash blankets, in the Ward, for Dr. DeWolf’s daughter, Mrs. Harrington; they were given to me by Mrs. DeWolf, who stated that Mrs. H. had no tub at her house large enough. The blankets had Ward marks on some of them.

That I was not called to give evidence at the investigation, believing that if I had been, and that I told all I knew, my time would be made short in the institution. That I am prepared, at any time, to substantiate, under oath, before any tribunal, the foregoing statement of facts. And I make this solemn declaration conscientiously, believing the same to be true, and by virtue of the Act passed in the thirty-seventh year of Her Majesty’s reign, entituled: (sic) “An Act for the Suppression of Voluntary and Extra Judicial Oaths.”

KATE CAMERON. Solemnly declared before me, at River Inhabitants, in the Island of Cape Breton, this 5th day of March, A.D. 1879. John McMaster, J. P.

The following is a copy of Dr. DeWolf’s letter announcing the death of Mrs. Turpel to her son:

10th December, 1874.

Mr. Alexander Turpel: Dear Sir, — I have to inform you, with much regret, of your mother’s decease, which occurred at an early hour this morning. I was called to her, but life was extinct. She had been better than usual of late, and was much attached to her attendant. Her death was due to a fit of paralysis, and was very sudden. Please telegraph whether you wish the interment to be in Dartmouth. I sent you a despatch this morning, which will have reached you ere this come to hand. Dear Sir, Sympathetically, J.R. DeWolf.

The Medical Superintendant’s Report for 1874 concludes as follows:

“It now remains to express our sincere gratitude to the Supreme Being for past mercies, and to invoke His blessing upon our future labors. The last hour of the old year was spent by a large number of attendants and many of the patients, in our chapel, where songs of grateful praise resounded at the solemn midnight hour, and ushered in the coming year. James R. DeWolfe, M.D. Superintendent.

“Supplementary evidence as to the management of the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane, Mount Hope, Dartmouth” [S.l. : s.n., 1879?] https://hdl.handle.net/2027/aeu.ark:/13960/t3tt5cc6m

A history and geography of Nova Scotia

“Dartmouth, which was settled in the year after the founding of Halifax, suffered most from the [Mi’kmaq]. Six men belonging to this place were attacked whilst cutting wood in the forest; four of them were killed and scalped, and one was taken prisoner. A few months afterwards, the [Mi’kmaq], having crept upon the settlement during the night, killed and scalped several of the panic stricken inhabitants. The screams of the terrified women and children were heard across the harbour in Halifax. The governor and council, unwisely adopting the barbarous custom of the [Mi’kmaq], offered large rewards for [indigenous] prisoners and [indigenous] scalps.”

“Dartmouth (4300) is about a mile from Halifax, on the opposite side of the harbour. It has various manufactures, among them are hempen rope and skates of superior quality. Near the town is the Provincial Lunatic Asylum.”

Calkin, John B. “A history and geography of Nova Scotia” Halifax, N.S. : A. & W. Mackinlay, 1878. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.11993/1?r=0&s=1

Nova Scotia, its climate, resources and advantages

“Opposite the city stands the pretty little town of Dartmouth, containing a population of about three thousand. A couple of miles south of Dartmouth, opposite the centre of the city of Halifax, on a commanding site, is the Provincial Asylum for the Insane, a very large, handsome stone building capable of accommodating 300 patients. The scenery around Halifax and Dartmouth, is charming… The Dartmouth lakes.. also present some beautiful landscapes.”

Crosskill, Herbert. “Nova Scotia, its climate, resources and advantages : being a general description of the province for the information of intending emigrants” Halifax [N.S.] : Province of Nova Scotia, 1872 (Halifax [N.S.]; C. Annuad) https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.03628/65?r=0&s=1

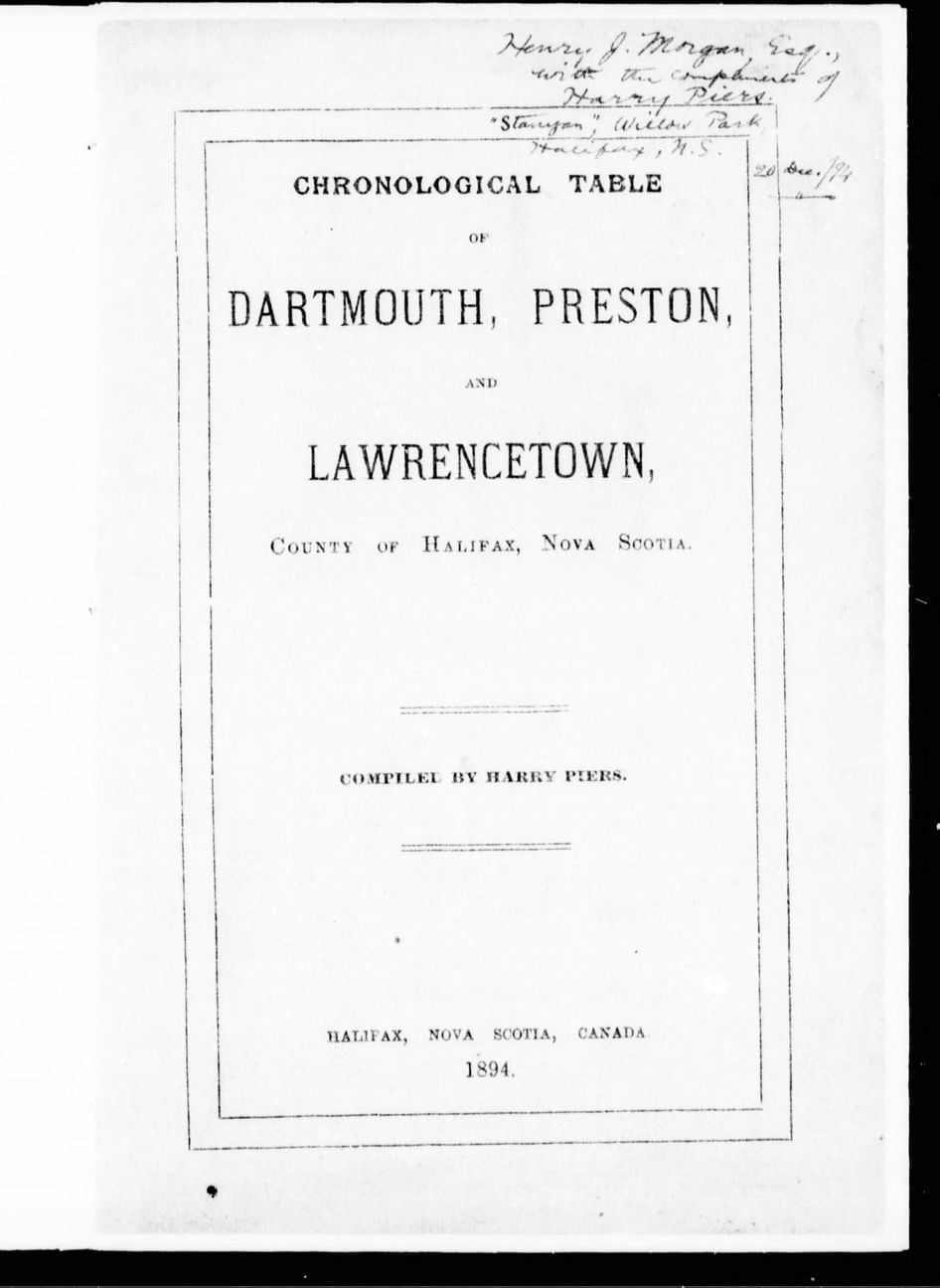

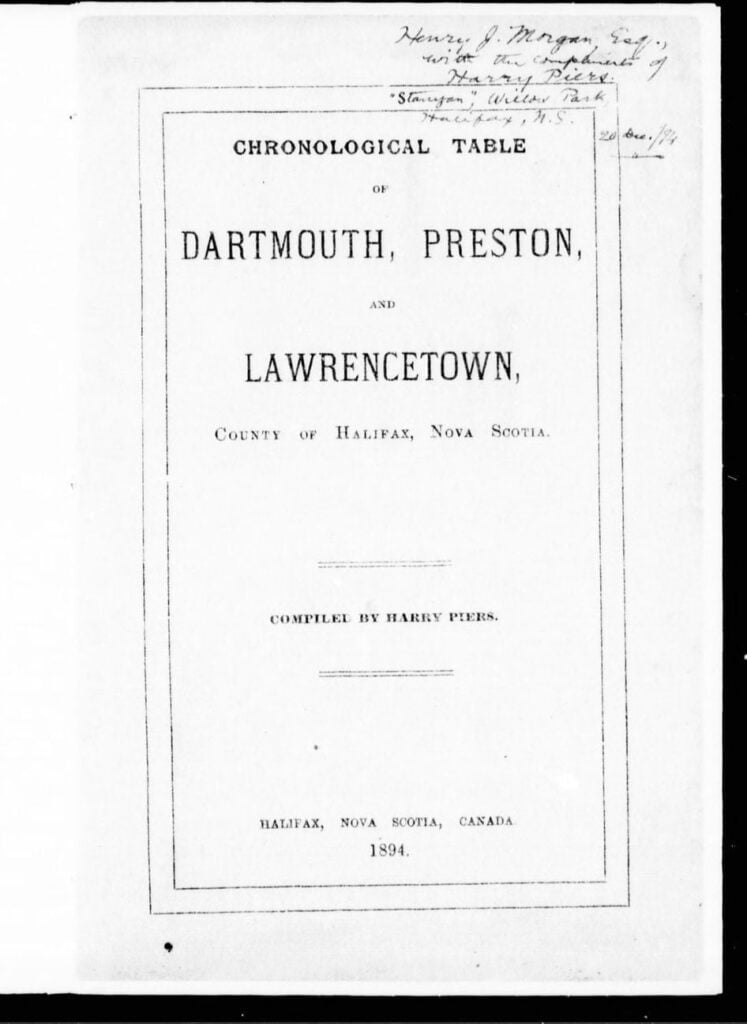

Chronological Table of Dartmouth, Preston, and Lawrencetown

Between 1746 and 1894, Dartmouth’s history unfolds with significant events including the arrival of settlers, establishment of saw-mills, and conflicts with the Mi’kmaq people. Dartmouth saw fluctuations in population, the building of churches and other infrastructure, and incorporation as a town in 1873. Economic activities like shipbuilding, ferry services, and the discovery of gold at Waverley mark periods of prosperity. However, tragedies such as fires, mysterious disappearances, and drowning incidents also punctuate Dartmouth’s timeline.

The town experienced advancements such as the introduction of steamboats, electricity, and the establishment of amenities like bathing houses and public reading rooms. Infrastructure projects like railway construction, water supply, and sewerage systems reflect efforts to modernize Dartmouth. Despite setbacks like bridge collapses and refinery closures, the town continued to evolve and grow, reaching a population of over 6,000 by 1891.

1746-1799

- Duc d’Anville arrived at Chebucto, 10 Sept 1746

- Halifax founded, 21 June 1749

- [Mi’kmaq] attacked 6 men at Maj. Gilman’s saw-mill, Dartmouth Cove, killing 4, 30 Sept 1749

- Saw-mill let to Capt. Wm. Clapham, 1750

- Alderney arrived from Europe with 353 settlers, Aug. 1750

- Town of Dartmouth laid out for the Alderney emigrants, Autumn 1750

- Order issued relative to guard at Dartmouth, 31 Dec. 1750

- Sergeant and 10 or 12 men ordered to mount guard during the nights at the Blockhouse, Dartmouth, 23 Feb. 1751

- [Mi’kmaq] attacked Dartmouth, killing a number of the inhabitants, 13 May, 1751

- German emigrants arrived at Halifax and were employed in picketing the back of Dartmouth, July 1751

- Ferry established between Dartmouth and Halifax, John Connor, ferryman, 3 Feb. 1752

- Mill at Dartmouth sold to Maj. Ezekiel Gilman, June 1752

- Population of Dartmouth 193, or 53 families, July 1752

- Advertisement ordered for the alteration of the style [Introduction of the Gregorian calendar], 31 Aug. 1752

- Permission given Connor to assign ferry to Henry Wynne and William Manthorne, 22 Dec 1752

- Township of Lawrencetown granted to 20 proprietors, 10 June 1754

- Fort Clarence built, 1754

- John Rock appointed ferryman in place of Wynne and Manthorne, 26 Jan. 1756

- Troops withdrawn from Lawrencetown by order dated, 25 Aug, 1757

- Dartmouth contained only 2 families, 9 Jan 1762

- Phillip Westphal (afterwards Admiral), born, 1782

- Preston Township granted to Theophilus Chamberlain and 163 others, chiefly loyalists, 15 Oct, 1784

- Free [black people] arrived at Halifax and afterwards settled at Preston, Apr., 1785

- George Augustus Westphal (afterwards Sir) born, 1785

- Whalers from Nantucket arrived at Halifax, 1785

- Town lots of Dartmouth escheated [See also] in order to grant them to the Nantucket whalers (Quakers), 2 Mar, 1786

- Grant of land at Preston to T. Young and 34 others, 20 Dec. 1787

- Common granted to inhabitants of Dartmouth [District, aka Township], 4 Sept. 1788 [Oct 2, 1758?] [–see also: “For regulating the Dartmouth Common, 1841 c52“]

- First church at Preston consecrated (on “Church Hill”), 1791

- Free [black people] departed for Sierra Leone, 15 Jan, 1792

- Nantucket Whalers left Dartmouth, 1792

- Francis Green built house (afterwards “Maroon Hall”) near Preston, 1792

- Dartmouth, Preston, Lawrencetown and Cole Harbour erected into parish of St. John, Nov. 22, 1792

- M. Danesville, governor of St. Pierre, arrived at Halifax (afterwards lived at “Brook House”), 20 June 1793

- Act passed to build bridge of boats across the Harbour (1796, c7), 1796

- Maroons arrived at Halifax (afterwards settled at Preston), 22 or 23 July, 1796

- Subject of a canal between Minas Basin and Halifax Harbour brought before the legislature, 1797

- Col. W.D. Quarrell returned to Jamaica, Spring 1797

- Capt. A. Howe took charge of Maroons, Ochterloney having been removed, 1797

- John Skerry began running ferry, about 1797

- Howe removed and T. Chamberlain appointed to superintend Maroons, 9 July, 1798

- Heavy storm did much damage, 25 Sept, 1798

- Mary Russell killed by her lover, Thomas Bembridge, at her father’s house, Russell’s Lake, 27 Sept. 1798

- Bembridge executed at Halifax, 18 Oct, 1798

1800-1849

- Maroons left Halifax, Aug 1800

- “Maroon Hall” sold to Samuel Hart, 8 Oct, 1801

- Town of Dartmouth said to have contained only 19 dwellings, 1809

- S. Hart died at “Maroon Hall” (property afterwards sold to John Prescott), 1810

- United States prisoners of war on parole at Dartmouth, Preston, etc. About 1812-1814

- Terrible gale, much damage to shipping 12 Nov 1813

- Gov Danseville left “Brook House”, 1814

- [Black people] arrived from Chesapeake Bay, 1 Sept 1814

- Smallpox appeared in Dartmouth, Preston, etc., Autumn, 1814

- Margaret Floyer died at “Brook House”, 9 Dec 1814

- Act passed to incorporate Halifax Steamboat Co., 1815

- Act passed allowing substitution of team-boats for steamboats by the company just mentioned, 1816

- Team-boat Sherbrooke launched, 30 Sept, 1816

- The team-boat made its first trip, 8 Nov., 1816

- Foundation stone of Christ Church laid, 9 July, 1817

- John Prescott died at “Maroon Hall” (property afterwards sold to Lieut. Katzmann), 1821

- Ninety Chesapeake Bay [black people] sent to Trinidad, 1821

- Dartmouth Fire Engine Co. established, 1822

- Lyle’s and Chapel’s shipyards opened, About 1823

- Act passed to authorize incorporation of a canal company, 1824

- Theophilus Chamberlain died, 20 July, 1824

- Joseph Findlay became lessee of Creighton’s ferry, About 1824

- Shubenacadie Canal Co. incorporated by letters patent, 1 June, 1826

- Ground first broken on canal, at Port Wallace, 25 July, 1826

- Consecration of church at Preston which had been built to replace the one consecrated in 1791, 1828

- Congregation of Church of St. James (Presbyterian) formed, Jan (?), 1829

- St. Peter’s Chapel commenced at Dartmouth, 26 Oct. 1829

- J. Findlay succeeded by Thos. Brewer at Creighton’s Ferry, About 1829-30

- Sir C. Ogle launched (first steamboat on ferry), 1 Jan, 1830

- Sixteen persons drowned by the upsetting of one of the small ferry boats, 14 Aug, 1831

- Ferry steamboat Boxer launched, 1832

- Brewer retired, and Creighton’s or the lower ferry ceased to exist, About 1832-33

- A. Shiels started Ellenvale Carding Mill, July, 1834

- Cholera in Halifax, Aug to Oct 1834

- William Foster built an ice-house near the lakes, 1836

- “Mount Amelia” built by Hon. J.W. Johnston, About, 1840

- Death of Meagher children, Jane Elizabeth, and Margaret, in woods near Preston (bodies found 17 April), April 1842

- Adam Laidlaw began ice-cutting on a large scale, 1843

- Dartmouth Baptist Church organized, 29 Oct, 1843

- Death of Lieut. C. C. Katzmann at “Maroon Hall”, 15 Dec, 1843

- Ferry steamboat Micmac build, 1844

- Dartmouth Baptist meeting-house opened, Sept, 1844

- Cole Harbour Dyke Co. incorporated, 28 Mar., 1845

- Incorporation of Richmond Bridge Co. (J.E. Starr, A.W. Godfrey, etc.) for purpose of erecting bridge of boards across Harbour, 14 April, 1845

- Mechanics’ Institute building erected, 1845

- Col. G. F. Thompson’s wife, said to have been a cousin of the Empress Eugenie, died under suspicious circumstances at “Lake Loon”, 20 Sept., 1846

- First regatta on Dartmouth Lake, 5 Oct, 1846

- Dr. MacDonald mysteriously disappeared, 30 Nov, 1846

- Mechanic’s Institute building opened, 7 Dec, 1846

- Second church at Preston (in the “Long swamp”) destroyed by fire, June (?), 1849

1850-1894

- Third C. of E. church built at Preston, near Salmon River, About 1850-1851

- Subenacadie Canal sold to government of N.S. (McNab, trustee), 1851-52

- Inland Navigation Co. incorporated, 4 April, 1853

- Methodist Church dedicated at Dartmouth, 1853

- Canal purchased by Inland Navigation Co., 10 June, 1854

- Mount Hope Insane Asylum cornerstone laid, 9 June, 1856

- “Maroon Hall” burnt, June, 1856

- Dartmouth Rifles and Engineers organized, Spring 1860

- Checbucto Marine Railway Co. formed by A. Pillsbury, 1860

- Gold discovered at Waverley, 1861

- Lake and River Navigation Co. purchased Canal, 18 June, 1862

- Dartmouth Rifles disbanded, 1 July, 1864

- Dartmouth Axe and Ladder Co,. formed, 1865

- Dartmouth Ropewalk began manufacturing, Spring, 1869

- Ferry steamboat Chebucto built, About 1869

- Prince Arthur’s Park Co. incorporated, 1870

- New St. James’s Church (Presbyterian) built, 1870

- Lewis P. Fairbanks purchased the canal from the Lake and River Navigation Co., Feb, 1870

- Population of town of Dartmouth, 3,786, 1871

- Dartmouth incorporated, 30 April, 1873

- Union Protection Co. organized, 1876

- Andrew Shiels, “Albyn”, died, 5 Nov, 1879

- New Baptist Church opened, 4 Jan, 1880

- Sandy Cove bathing houses opened at Dartmouth, 7 Aug, 1880

- Foundation-stone of Woodside Refinery laid, 3 July, 1883

- Railway to Dartmouth commenced, 1885

- Railway opened for business, 6 Jan, 1886

- Halifax and Dartmouth Steam Ferry Co. formed, in place of old company, 1886

- Woodside Refinery closed, Dec, 1886

- Ferry steamboat Dartmouth built, 1888

- Public Reading-Room opened, 1 Jan, 1889

- Dartmouth Ferry Commission formed, 17 April, 1890

- Ferry Co. sells its property to the commission, 1 July, 1890

- Several persons drowned on the arrival of the ferry-boat Annex 2 (Halifax), 11 July, 1890

- New St. Peter’s Chapel begun, Autumn, 1890

- Act passed to provide for supplying Dartmouth with water and sewerage, 19 May, 1891

- Narrows railway bridge carried away, 7 Sept., 1891

- Trenching and laying the main water pipe begun, 3 Oct., 1891

- Woodside Refinery again opened, 1891

- Population of town of Dartmouth, 6,252, 1891

- St. Peter’s chapel opened, 7 Feb., 1892

- Dartmouth first lighted by electricity, 13 July, 1892

- Water turned on the town from Topsail and Lamont’s Lakes, 2 Nov, 1892

- Narrows bridge destroyed for second time, 23 July, 1893

- Woodside Refinery transferred to Acadia Sugar Refining Co., Aug, 1893

- New Post Office opened, 1 May, 1894

Piers, Harry, 1870-1940. Chronological Table of Dartmouth, Preston, And Lawrencetown, County of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Halifax, N.S.: [s.n.], 1894. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.12013/12?r=0&s=1, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/aeu.ark:/13960/t8pc3fx9z

The Development of Public Health in Nova Scotia