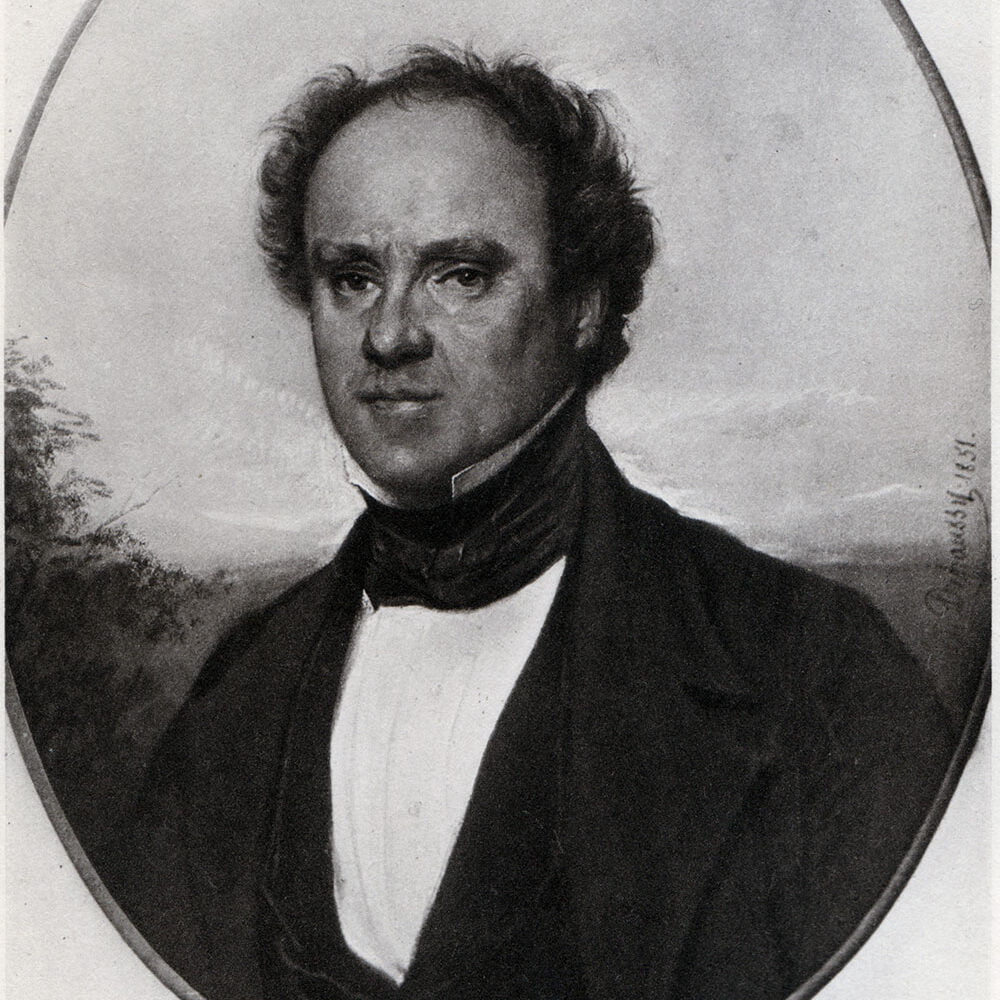

Joseph Howe’s Speech at Dartmouth, May 22nd, 1867, is a passionate lamentation, decrying the loss of Nova Scotian autonomy and self-governance to the Canadian government through confederation. He reminisced about the struggles over decades for self-government fought against British control, highlighting the achievements in areas such as governance, trade, taxation, militia organization, postal services, currency stability, banking, and savings institutions.

He expressed deep concern that these hard-won freedoms and systems were being eroded by the Canadian government, distant and uncaring, imposing its will on Nova Scotia without regard for its unique needs and experiences. He viewed the impending loss of control over crucial aspects of governance, economy, and finance as a betrayal, fearing increased taxation, economic instability, and exploitation of the populace by external interests. All of which came to pass.

Howe, one of our leading statesman and also, it appears, our prognosticator in chief, painted a vivid picture of a once-independent Nova Scotia being subjugated and marginalized within the larger Canadian federation, and the dire consequences for its economy, society, and autonomy that would result.

In opposing the British North America Act… (Joseph Howe) always urged that it was not acceptable to the people of Nova Scotia. As an election was soon to be held, to make good his statement Mr. Howe felt that he must organize his forces, and demonstrate beyond dispute that the Province of Nova Scotia was overwhelmingly opposed to the union. He returned early in May, and on May 22nd delivered at Dartmouth the following speech, in which he betrays no loss of his old-time warmth and vigour:

MEN OF DARTMOUTH —

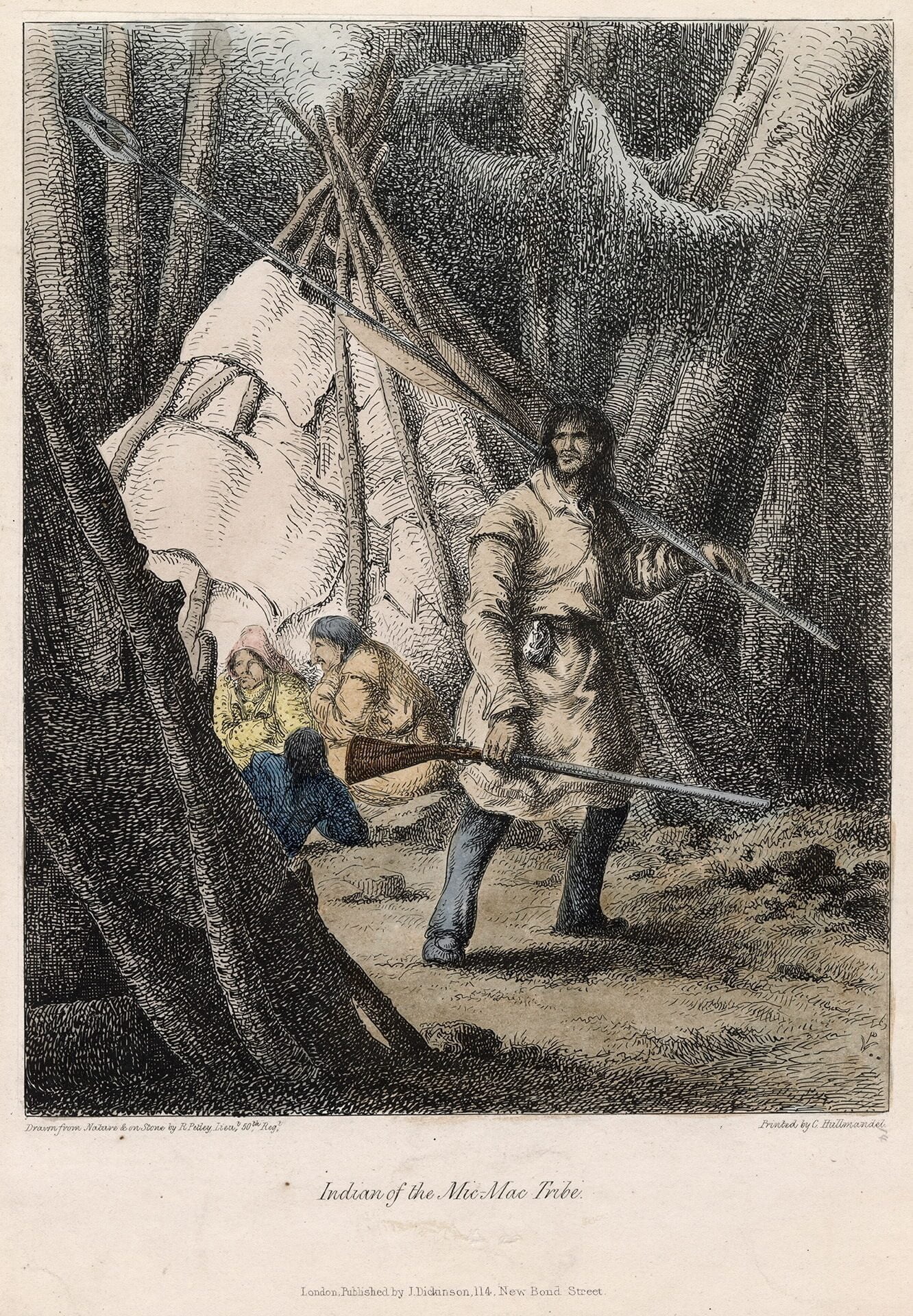

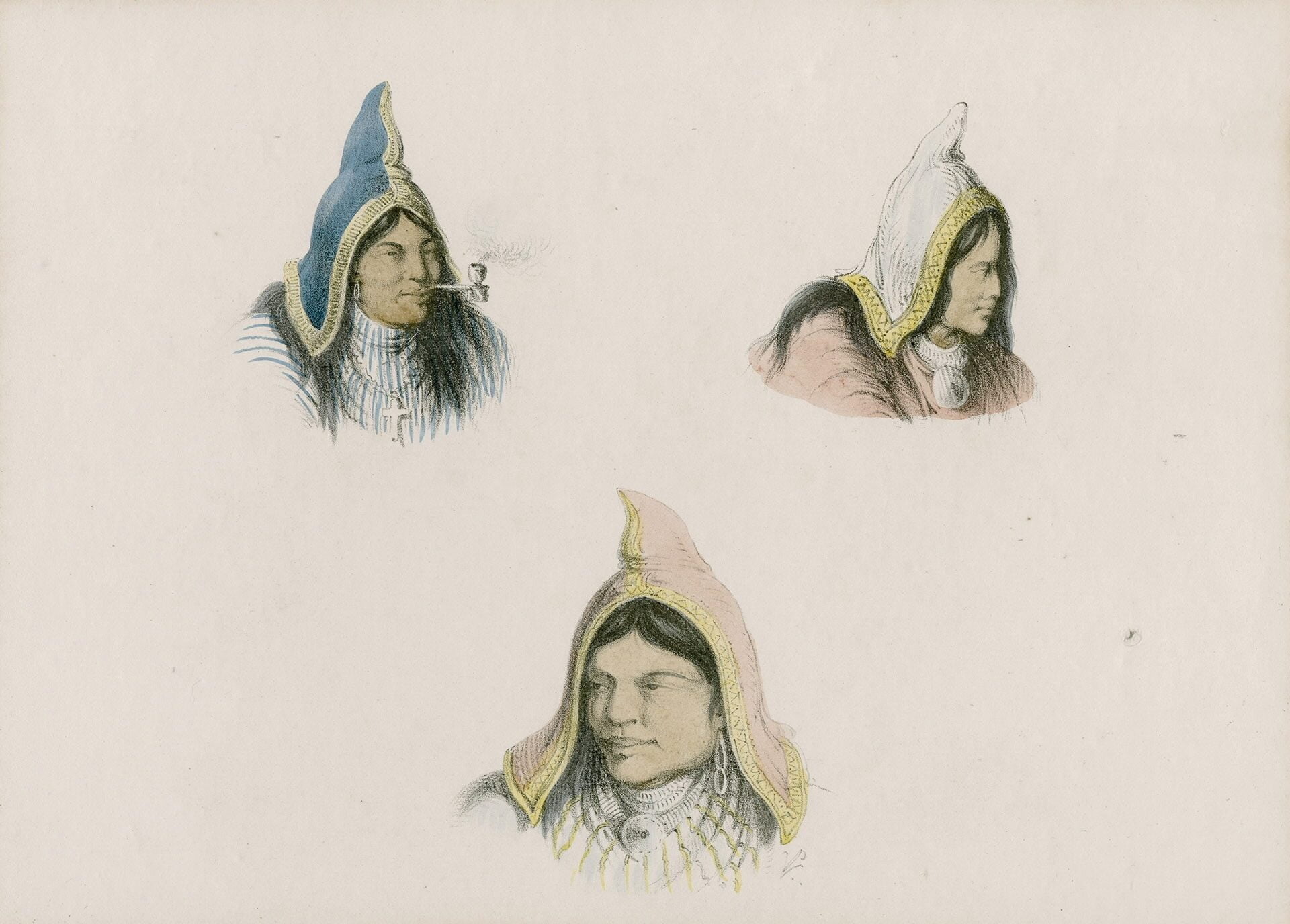

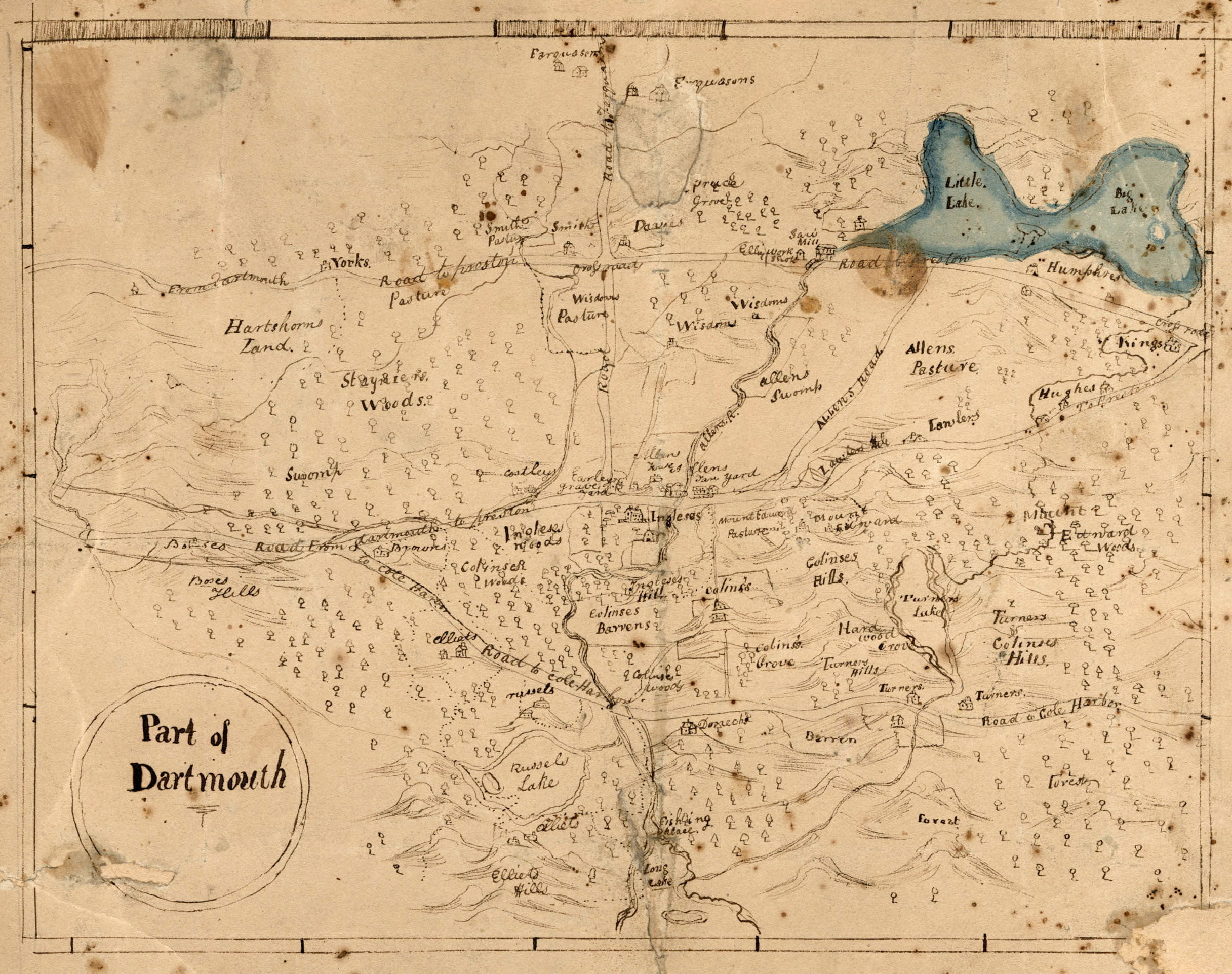

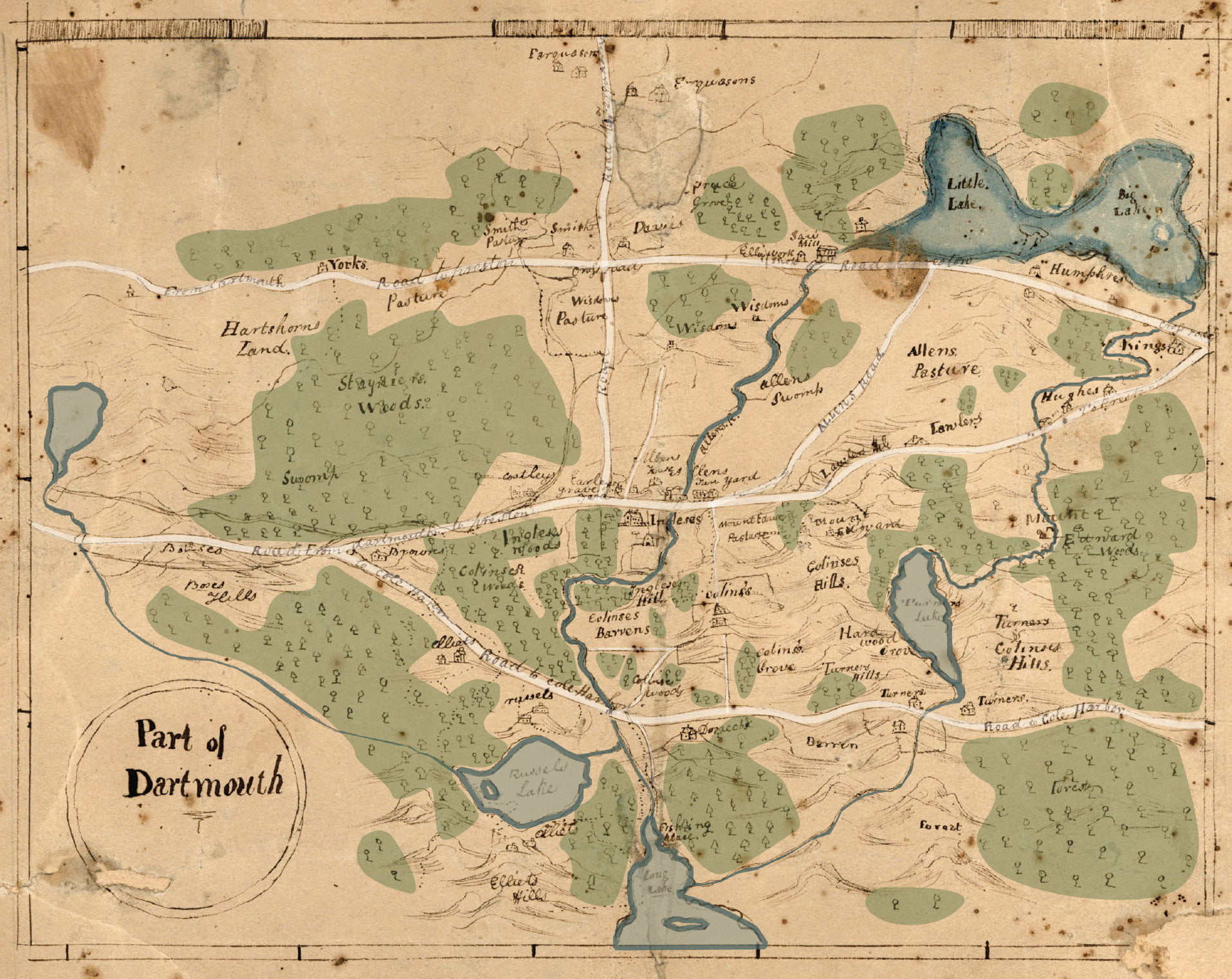

Never, since the [Mi’kmaq] came down the Shubenacadie Lakes in 1750, burnt the houses of the early settlers, and scalped or carried them captives to the woods, have the people upon this harbour been called upon to face circumstances so serious as those which confront them now. We may truly say, in the language of Burke, that “the high roads are broken up and the waters are out,” and that everything around us is in a state of chaos and uncertainty. A year ago Nova Scotia presented the aspect of a self-governed community, loyal to a man, attached to their institutions, cheerful, prosperous and contented. You could look back upon the past with pride, on the present with confidence, and on the future with hope.

Now all this has been changed. We have been entrapped into a revolution. You look into each other’s faces and ask, What is to come next? You grasp each other’s hands as though in the presence of sudden danger. You are a self-governed and independent community no longer. The institutions founded by your fathers, and strengthened and consolidated by your own exertions, have been overthrown. Your revenues are to be swept beyond your control. You are henceforward to be governed by strangers, and your hearts are wrung by the reflection that this has not been done by the strong hand of open violence, but by the treachery and connivance of those whom you trusted, and by whom you have been betrayed.

The [Mi’kmaq] who scalped your forefathers were open enemies, and had good reason for what they did. They were fighting for their country, which they loved, as we have loved it in these latter years. It was a wilderness. There was perhaps not a square mile of cultivation, or a road or a bridge anywhere. But it was their home, and what God in His bounty had given them they defended like brave and true men. They fought the old pioneers of our civilization for a hundred and thirty years, and during all that time they were true to each other and to their country, wilderness though it was. There is no record or tradition of treachery or betrayal of trust among these [Mi’kmaq] to parallel that of which you complain.

Let us, in imagination, do them the injustice they do not deserve, and assume that six of their young men went over and sold them to the Milicetes of New Brunswick or to the Penobscots of Maine. What would have happened? Would the old men, on their return, have folded them to their bosoms, or the young braves have trusted them again? No,—the tomahawk and the fire would have been their reward, and the duty of honour and good faith would have been illustrated by a terrible example. The race is mouldering away, but there is no stain of treason on its traditions. Even in its day of decadence and humiliation it challenges respect, and when the last of the [Mi’kmaq] bows his head in his solitary camp and resigns his soul to his Creator, he may look back with pride upon the past, and thank the “Great Spirit” that there was not a Tupper or a Henry, an Archibald or a McCully in his tribe.

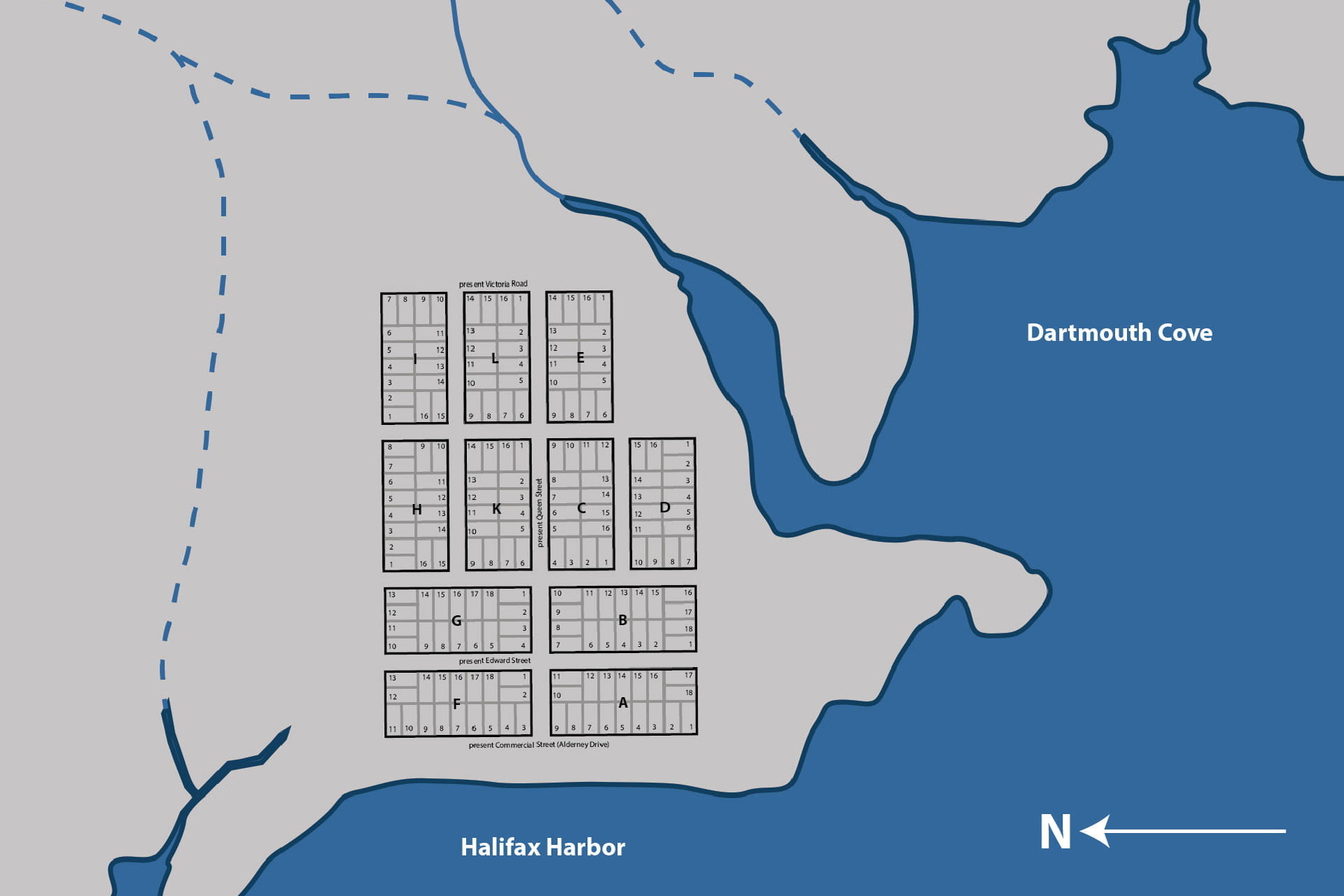

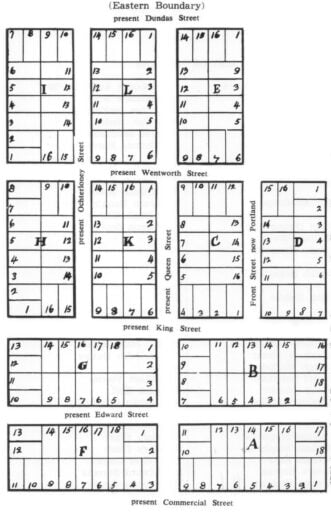

Look again at that dreary and uncertain hundred and thirty years which preceded the foundation of Halifax, which Beamish Murdoch (whose book it always gives me pleasure to recommend) so carefully delineates, and you will find that even among the earlier explorers and occupants of our western counties, fitful and uncertain as were their fortunes, there were fidelity and honour. When Halifax and Dartmouth were founded, when there were but a few thousand men upon this harbour, living within palisades and defended by block-houses—when an impenetrable wilderness lay behind them, and the woods were full of [Mi’kmaq] and of French, we hear of no treachery, of no betrayal of trust.

The “forefathers of our hamlets” were true to each other. They toiled in the belief that they were founding a noble Province that their posterity would govern. The loyalists, who came in great numbers during the revolutionary war, cherished the same belief, and never dreamed that the Province they were strengthening by their intelligence and industry was to be wrested from their descendants and governed by Canadians. The Scotch emigrants who flowed into our eastern counties came, attracted by a name they loved, to govern themselves, and transmit the country untrammelled to their descendants. The Irish, fleeing from a land that had been swindled out of its legislature, fondly believed that here they would find the freedom and the self-dependence they had sighed for at home. For ninety years all these industrial, intellectual and social elements, fusing into an active and high-spirited community, were led and guided by able and patriotic men, now no more.

In fancy I can see them ranged around me in a noble historic gallery—Colonel Barclay and Isaac Wilkins, Sampson Salter Blowers, Foster Hutchinson, and many others. Was there one among them all who would have sold his country? Coming down to a later period, we find men of whom we are not ashamed. We are sometimes told that small countries produce small men, but John Young, Robie, Fairbanks, Bliss, Doyle, Huntington, Uniacke, Bell, in breadth of view, brilliancy and knowledge were the equals of the best that Canada ever produced. Which of these men would have sold Nova Scotia, or delivered her over, bound hand and foot, without the consent of her people to the government of strangers? There is not one whose picture would not start from the wall, whose bones would not rattle in the grave, at the very suspicion.

Sir, there is one name, that of S. G. W. Archibald, that among this fine fraternity is invested with a rare lustre in comparison with the recent achievement of one who has earned unenviable notoriety. When the rights and powers of our Parliament were menaced he defended them, and even though the immediate matter in dispute was but 4d. a gallon upon brandy, like the ship-money of old, it involved a principle, and Archibald defended the rights of the House, and the independent action in all matters of revenue and supply of the people of Nova Scotia. Gratefully is the act remembered, and now that we have seen all our revenues and the united power of taxation transferred to strangers, is it surprising that we should wish that the person who has perpetrated this outrage should have found another name?

The old men who sit around me, and the men of middle age who hear my voice, know that thirty years ago we engaged in a series of struggles which the growth of population, wealth and intelligence rendered inevitable. For what did we contend? Chiefly for the right of self-government. We won it from Downing Street after many a manly struggle, and we exercised and never abused it for a quarter of a century. Where is it now? Gone from us, and certain persons in Canada are now to exercise over us powers more arbitrary and excessive than any the Colonial Secretaries ever claimed. Our Executive and Legislative Councillors were formerly selected in Downing Street. For more than twenty years we have appointed them ourselves. But the right has been bartered away by those who have betrayed us, and now we must be content with those our Canadian masters give. The batch already announced shows the principles which are to govern the selection.

For many years the Colonial Secretary dispensed our casual and territorial revenues. The sum rarely exceeded £12,000 sterling, but the money was ours, and yielding at last to common sense and rational argument, our claims were allowed. But what do we see now? Almost all our revenues—not twelve thousand but hundreds of thousands—are to be swept away and handed over to the custody and the administration of strangers.

The old men here remember when we had no control over our trade, and when Halifax was the only free port. By slow degrees we pressed for a better system, till, under the enlightened commercial policy of England, we were left untrammelled to levy what duties we pleased and to regulate our trade. Its marvellous development under our independent action astonishes ourselves, and is the wonder of strangers.

We have fifty seaports carrying on foreign trade. Our shipyards are full of life and our flag floats on every sea. All this is changed: we can regulate our own trade no longer. We must submit to the dictation of those who live above the tide, and who will know little of and care less for our interests or our experience.

The right of self-taxation, the power of the purse, is in every country the true security for freedom. We had it. It is gone, and the Canadians have been invested by this precious batch of worthies, who are now seeking your suffrages, with the right to strip us “by any and every mode or system of taxation.”

We struggled for years for the control of our Post Office. At that time rates were high, the system contracted; offices had only been established in the shire towns and in the more populous settlements. We gained the control, the rates were lowered and rendered uniform over the Provinces, newspapers were carried free, offices were established in all the thriving settlements and way offices on every road, but now all this comes to an end. Our Post Offices are to be regulated by a distant authority. Every post-master and every way office keeper is to be appointed and controlled by the Canadians.

Since the necessity for a better organization of the militia became apparent, our young men have shown a laudable spirit of emulation and have volunteered cheerfully, formed naval brigades, and shown a desire to acquire discipline and the use of arms. I have viewed these efforts with special interest. There is no period in the history of England when the great body of the people were better fed, better treated, or enjoyed more of the substantial comforts of life, than when every man was trained to the use of arms, and had his long-bow or his cross-bow in his house.

The rifle is the modern weapon, and our people have not been slow to learn the use of it. Organized by their own Government, commanded by their friends and neighbours, 50,000 men have been embodied and partially drilled for self-defence. But now strangers are to control this force—to appoint the officers and to direct its movements; and while our own shores may be undefended, the artillery company that trains upon the hills before us may be ordered away to any point of the Canadian frontier.

By the precious instrument by which we are hereafter to be bound, the Canadians are to fix the “salaries” of our principal public officers. We are to pay, but they can fix the amount, and who doubts but that our money will be squandered to reward the traitors who have betrayed us? Our “navigation and shipping” pass from our control, and the Canadians, who have not one ship to our three, are already boasting that they are the third maritime power in the world. Our “sea-coast and inland fisheries” are no longer ours. The shore fisheries have been handed over to the Yankees, and the Canadians can sell or lease tomorrow the fisheries of the Margaree, the Musquodoboit or the La Have.

Our “currency,” also, is to be regulated by the Canadians, and how they will regulate it we shrewdly suspect. Many of us remember when Nova Scotia was flooded with irresponsible paper, and have not forgotten the commercial crisis that ensued. In one summer thousands of people fled from the country, half the shops in Water Street, Halifax, were closed, and the grass almost grew in the Market Square. The paper was driven in. The banks were restricted to five-pound notes. All paper, under severe penalties, was made convertible. British coins were adopted as the standard of value, and silver has been ever since paid from hand to hand in all the smaller transactions of life.

For a quarter of a century we have had free trade in banking, and the soundest currency in the world. Last spring Mr. Galt could not meet the obligations of Canada, and he could only borrow money at ruinous rates of interest. He seized upon the circulation, and partially adopted the greenback system of the United States. The country is now flooded with paper; only, if I am rightly informed, convertible in two places—Toronto and Montreal. The system will soon be extended to Nova Scotia, and the country will presently be flooded with “shin-plasters,” and the sound specie currency we now use will be driven out.

Our “savings banks” are also to be handed over. Hitherto the confidence of the people in these banks has been universal. We had the security of our own Government, watched by our own vigilance, and controlled by our own votes, for the sacred care of deposits. What are we to have now? Nobody knows, but we do know that the savings of the poor and the industrious are to be handed over to the Canadians. They also are to regulate the interest of money. The usury laws have never been repealed in Nova Scotia, and yet capital could always be commanded here at six, and often at five per cent. In Canada the rate of interest ranges from eight to ten per cent, and is often much higher. With confederation will come these higher rates of interest, grinding the faces of the poor.

But it is said, why should we complain? we are still to manage our local affairs. I have shown you that self-government, in all that gives dignity and – security to a free state, is to be swept away. The Canadians are to appoint our governors, judges and senators. They are to “tax us by any and every mode” and spend the money. They are to regulate our trade, control our Post Offices, command the militia, fix the salaries, do what they like with our shipping and navigation, with our sea-coast and river fisheries, regulate the currency and the rate of interest, and seize upon our savings banks.

What remains? Listen, and be comforted. You are to have the privilege of “imposing direct taxation, within the Province, in order to the raising of revenue for Provincial purposes.” Why do you not go down on your knees and be thankful for this crowning mercy when fifty per cent has been added to your ad valorem duties, and the money has been all swept away to dig canals or fortify Montreal. You are to be kindly permitted to keep up your spirits and internal improvements by direct taxation.

Who does not remember, some years ago, when I proposed to pledge the public revenues of the Province to build our railroads, how Tupper went screaming all over the Province that we should be ruined by the expenditure, and that “direct taxation” would be the result. He threw me out of my seat in Cumberland by this and other unprincipled war-cries. Well, the roads have been built, and not only were we never compelled to resort to direct taxation, but so great has been the prosperity resulting from those public works that, with the lowest tariff in the world, we have trebled our revenue in ten years, and with a hundred and fifty miles of railroad completed, and nearly as much more under contract, we have had an overflowing treasury, and money enough to meet all our obligations, without having been compelled, like the Canadians, to borrow money at eight per cent, and to manufacture greenbacks.

But if we had been compelled to pay direct taxes for a few years to create a railroad system that by-and-by would be self-sustaining, and that would have been a great blessing in the meantime, the object would have been worth the sacrifice. But we never paid a farthing. What then? The falsehood did its work. Tupper won the seat, and now, after giving our railroads away, and all our general revenues besides, the doctor, after being rejected by Halifax, is trying to make the people of Cumberland believe that to pay “direct taxes” for all sorts of services is a pleasant and profitable pastime. Cumberland may believe and trust him again, but if it does, the people are not so shrewd or so patriotic as I think they are.

But listen, you have another great privilege. What do you think it is? You are allowed “to borrow money.” But will anybody lend it? Most people find that they can borrow money easiest when they do not want it, but where is it to be got? The general government, who can tax you “by any and every mode,” and override your legislation as they please, have also power to borrow. If I know anything of the men who now rule the roost in Canada, they will screw every dollar out of you that you are able to pay, and borrow while there is a pound to be raised at home or abroad. Thus fleeced, and with the credit of the Dominion thus exhausted, who will lend you a sixpence should you happen to want it? Nobody who is not a fool. There is not a delegate among the lot who would lend £100 upon such security.

But you have other great privileges. Listen again. You are generously permitted to maintain “the poor,” and to provide for your “hospitals, prisons and lunatic asylums.” We have it on divine authority that the poor “will be always with us,” and come what may we must provide for them. What I fear is that, under confederation, the number will be largely increased, and that when the country is taxed and drained of its circulation, the rich will be poorer and the industrious classes severely straitened. The lunatic asylum of course we must keep up, because Archibald may want it by-and-by to put Tupper and Henry into at the close of the elections.

Keep cool, my friends. This precious instrument confers upon you other high powers and privileges. You are permitted to establish local courts, and to “fine and imprison” each other. And this brings me to the key to this whole “mystery of iniquity.” Local courts you may establish. The Supreme Court is to be transferred to the general government, which is to appoint the judges and fix the salaries. Our judges now receive £700 or £800 currency per annum. The judges in Canada get £1000 or £1250 currency. The delegation which represented Nova Scotia in Canada and England was composed of five lawyers and a doctor. What the doctor is to get we may see by-and-by, but the five lawyers expect to be judges. John A. Macdonald knew this very well, and when he opened his confederation mouse-trap he did not bait it with toasted cheese. Judgeships, with these high salaries, was the bait that he dangled before their noses. They were caught, and though they hated each other, and had spoken a good deal of severe truth of each other before they went to Quebec, the bait produced a marvellous effect upon them, and, like a happy family, they have lived in brotherly love ever since, wagging their tails just whenever Mr. Macdonald told them.

But this bait was intended to have effect outside the mere delegation—to influence judges and lawyers in all the provinces. The confederates tell us that in this Province all the judges and lawyers are in favour of this scheme. If it were so, we should perhaps not be much surprised. All the carpenters would be in favour of it if you could convince them that their wages would be doubled. Let us hope that this assertion is but a scandal.

The bar, certainly, is not all in favour of the scheme. Many high-spirited men in the profession loathe the very name of confederation. As respects the judges, whatever may be their opinions, let us hope that they have never expressed them. Among the other inestimable blessings which we have had in Nova Scotia has been a pure administration of justice—a spotless ermine, worn by men above suspicion of political bias or corruption. Let us hope that this distinction may be ours while our old constitution lasts. “Shadows, clouds and darkness” rest upon the future, and nobody can tell what we are to have next.

Hitherto we have been a self-governed and independent community, our allegiance to the Queen, who rarely vetoed a law, being the only restraint upon our action. We appointed every officer but the Governor. How were the 1867 high powers exercised? Less than a century and a quarter ago, the moose and the bear roamed unmolested where we stand. Within that time the country has been cleared—society organized. The Province has been intersected with free roads—the streams have been bridged—the coasts lighted— the people educated, and all the modern facilities afforded by cheap postage, telegraphs, and railroads were rapidly being brought to every man’s door, and the growth of our mercantile marine evinced the enterprise and indomitable spirit of the people. A few years since there were eleven “captain cards” upon the Noel shore.

Some time ago I went into a house in the township of Yarmouth. There was a frame hanging over the mantelpiece with seven photographs in it. “Who are these?” I asked, and the matron replied, smiling, “These are my seven sailor boys.” “But these are not boys, they are stout powerful men, Mrs. Hatfield.” “Yes,” said the mother, with the faintest possible exhibition of maternal pride, “they all command fine ships, and have all been round Cape Horn.” It is thus that our country grew and throve while we governed it ourselves, and the spirit of adventure and of self-reliance was admirable. But now, “with bated breath and whispering humbleness,” we are told to acknowledge our masters, and, if we wish to ensure their favour, we must elect the very scamps by whom we have been betrayed and sold.

But we are told that we ought to be reconciled to all this because we are to have the Intercolonial Railroad, and because, financially, the delegates have made so good a bargain. If you will bear with me a few moments I will dissipate this delusion. I am speaking from memory, and my figures may not be strictly accurate. But in the main they will be found correct, and the argument based upon them is irresistible.

When I went into the Legislature in 1837 our revenue was about £60,000. It only doubled in seventeen years, before we commenced building our railroads. In 1854 we passed our railroad laws, and in 1855 Tupper went screaming all over Cumberland, prophesying ruin and decay. In ten years since then our revenues have trebled, and last year amounted to £400,000. We have built the road to Truro, the road to Windsor, the extension to Pictou; and before this precious bargain and sale of all our resources was consummated we had the Northern road to New Brunswick, all of the Intercolonial within our borders, and the road to Annapolis under contract.

We had money enough to pay for all these roads without being under any compliment to the Canadians or the British Government either; and in ten years more, without financial embarrassment, could have extended our system to Yarmouth on the one side, and to Sydney on the other. At this moment it was—with my railroad policy so successful—the country, that Tupper swore I had ruined, so prosperous—the treasury, which he declared was milked dry, overflowing year by year, under the tariff we bequeathed to him, and our debentures two or three per cent above the bonds of Canada—that we were sold like sheep. This was the moment for these delegates to step in and trade us away, our rights and revenues, to Canada. God help us, and enable us “to possess our souls in patience.” No such deed as this was ever done or attempted where death was not the penalty.

I cannot help smiling when I hear Tupper crowing about the railroads he has built. He ought to be ashamed of vain boasting. We all know, and he knows, that had his warning voice been heeded, there never would have been a mile of railroad built in Nova Scotia up to this hour. The roads to Windsor and to Truro were built upon the policy inaugurated by myself, and with the money borrowed by me in England. What had he to do with it? Just this— that the Government having changed, he and his colleagues paid away about £40,000 of your money to a parcel of contractors who set up irregular claims. All the roads made since have been made on my policy of pledging the public credit to make them, which Tupper declared would be ruinous. There has been, however, an important difference in the mode of dealing with contracts and expending the money, which ought to be held up to indignant reprobation.

When I was at the head of the Railway Board I was surrounded by six business men, an accountant, and an engineer. Every mile of road was thrown open to competition by tender and contract. When tenders were sent in they were placed in custody of the accountant till the time expired, and the whole board assembled. I never looked at one of them till they were opened in presence of all the commissioners, the accountant, and engineer. The lowest tender, if the party produced good security, took the contract, without reference to politics, to country, or to creed. Look at the new system inaugurated by Dr. Tupper. Take the Pictou line as an illustration. A number of our own people tendered for the work. If kindly treated, some of them might have pulled through. If they did not, their bondsmen were liable. By a system of dealing, instead of the work being put up to tender again, the whole was handed over to the engineer by private bargain, a system most unfair to the whole people, and open to suspicion of gross favouritism and corruption. Instead of offering the northern and western lines to fair competition, the Government took powers to hand them over, by private bargain, to whomever they chose to select. I do not say, because I cannot prove, that any of the members of the Government were sleeping partners, or profited by these contracts. But I do say that the system was most perilous to the public interests, and open to grave objections. We pray to be “kept out of temptation,” but these gentlemen, with profitable contracts to dispose of, amounting to nearly a million and a half of money, exposed themselves to temptations hard to resist, and laid themselves open to suspicions widely entertained. I left the Railway Board as poor as I went into it. I bought or built no property then or since. I hope those who succeeded to the administration have left with hands as clean.

Let me turn your attention, now, to the bargain that has been made with Canada. We give them the roads already completed, which have cost nearly a million and a half. We give them the roads under contract, which may cost another million. We give them revenue enough to cover the interest upon these roads, till they pay, when they will get them for nothing, and have the revenue besides. Our whole revenue now amounts to £400,000. It has trebled in ten years. If it only doubles in the next ten we will have £800,000. By that time our old roads will pay, and the new ones yield half the interest. Out of this sum we are to get back of our own money £133,000, a sum utterly inadequate to provide for Provincial services now, and by that time deplorably insufficient. We can only provide for those services by direct taxation. The Canadians get all the rest.

Hitherto I have reasoned upon a ten per cent. tariff, which would have provided for all our wants, and given a fund for railway extension to the extremities of the Province, east and west. But we know that under confederation our tariff will be raised to fifteen per cent. If the revenue is collected, taking our Customs duties at $1,231,902, the additional taxation will take out of our pockets $500,000 the very first year. The interest on the £3,000,000 required for the Intercolonial road is £120,000 sterling. The road will take four years to construct. The Canadians will only pay interest as the work goes on, yet from the start they will take out of our pockets by increased duties, to say nothing of the general revenues surrendered, £100,000 sterling, a sum nearly sufficient to pay the interest on the whole three millions. This is the profitable bargain they have made, and they have the audacity to suppose that Nova Scotians are such idiots that they can cover up the transaction with every species of falsehood and mystification. They shall not do this. It shall be presented to the people everywhere in its naked deformity and injustice, and when it is they will pronounce universal condemnation. You have been told that Mr. Annand, Mr. McDonald, and I opposed the Intercolonial Railroad. Why, if the bargain had been a good one, we would have flung the road to the winds to save the independence of the Province, but being what it is, a fraud upon the revenues and an insult to the common sense of Nova Scotia, we did our best to defeat it.

But confederation will bring with it other blessings. Stamp duties, hitherto unknown, will soon be imposed, and toll-bars will become ornaments of the scenery. We have but two toll bridges in the Province, and all our roads are free. In Canada you can hardly travel five miles without being stopped by a toll-bar, and compelled to pay for the use of the road. Our newspapers now go free, but they will soon be taxed as they are in Canada. For all these mercies should we not be thankful to the delegates? Yes, as thankful as men are for the plague or the smallpox.

But we are told when we complain of this fraudulent conveyance of our independence—of this reckless sacrifice of our dearest interests, that we are disloyal—that we are annexationists, Fenians, and dangerous persons. Are we indeed?

A year ago there was no annexationist in Nova Scotia. If there are any now, we have to thank those who have overthrown our institutions, and treated the population with contempt. This old cry of disloyalty does not terrify me. It has been raised by some interested faction at every crisis of our Provincial history. I met it at the outset of my public life, and trampled the accusation under my feet in the old trial with the magistrates of Halifax. I met it again at the outbreak of the Canadian rebellion, and put the enemy to shame by the publication of my letter to Chapman. The records are here, and he who runs may read.

[Holding up a volume of speeches.] Surrounded by the élite of Massachusetts, all the Yankees eminent in station and distinguished by talent, I have vindicated the institutions and upheld the honour of Great Britain. You know—these wretched slanderers know—how at Detroit, before the commercial representatives of the Provinces and of the Northern States, I won the respect of our neighbours by the triumphant vindication of British interests; and won what, perhaps, I valued as much, the thanks of my Sovereign, conveyed to me by the Secretary of State. But Dr. Tupper accuses me of disloyalty, does he, and sets his newspapers, subsidized with public plunder, to asperse better men than himself?

Let me contrast his conduct with my own. During the Crimean war our army was decimated by the great battles of the Alma, Balaclava and Inkerman. Surrounded by hordes of Russians, and suffering for supplies, there was some risk that they might be driven into the sea. Reinforcements were urgently required, and a Foreign Enlistment Act was passed. To assist in carrying out that Act I risked my life for two months in the United States, surrounded by Russian agents, American sympathisers, and Fenians. Mr. Gibson, now in this room, was in New York at the time, and knew the state of feeling, and urged me to quit the service and not risk imprisonment or personal violence. I persevered, rarely sleeping twice in the same bed till recalled; and this I did for England in her hour of peril, and never received a pound for my services, or asked one.”

Now, what was Dr. Tupper doing at this time? He was scouring the county of Cumberland while I was absent on the service of the Crown, meanly endeavouring to deprive me of my seat. He slandered me in every part of the county—he invented stories that I was imprisoned and would not be back. I only got back a few days before the election, too late for any canvass or efficient organization, and was defeated, of course. In this dishonourable mode he won the seat he now holds, and certainly illustrated his devotion to his Sovereign after a mode that ought to be remembered. At a later period, in 1862, when, foreseeing the dangers which have since threatened these Provinces, my Government revived the militia law and increased the annual grant for defence, did not this very loyal gentleman endeavour to reduce the Governor’s salary, to deprive him of the vote for a secretary, and to strike out $8000 of the grant for the militia upon the ground that the Province was so poor that it could not afford the expense?

I pass by this “retrenchment scheme” as utterly beneath contempt. I pass by the wretched jobs by which his administration has been distinguished – from its commencement to its close. Let me waste a few words on the cry that “we ought to send the best men”—by which, of course, these precious delegates mean themselves. The best men of this lot, bad is the best. Now the best men to send are not scheming lawyers, who would dig up and sell their fathers’ bones for money or preferment, but honest men in whom the people of this country have entire confidence. Dr. Tupper has already chosen his twelve senators, and now he wants to be allowed to choose the people’s representatives. Why should he not? You were too stupid to pass an opinion upon confederation. Are you sure that you have sense enough to choose a representative?

The “best men”!—let us see how he has chosen. In the first place he has taken six senators from one county, leaving eleven counties entirely unrepresented. Then he has taken three men who were open and avowed anti-confederates; who ratted, sold themselves, and were purchased by the distinction. A friend came in and told me last spring that he was afraid Bill was being tampered with, as he saw Tupper taking him up to Government House that morning. I discredited the story, because I did not believe that the Queen’s representative would degrade his office by canvassing and tampering with members of the House. I think so still. No doubt the visit was one of mere form, but Caleb’s name appears in the list of Ottawa senators, and who doubts how his sudden conversion was effected? Compare him with McHeffy, who is in gentlemanly manners, intelligence and sturdy independence, out of sight his superior. Yet the best man is left behind because he would not sell his country. Who does not remember Miller denouncing the confederation scheme on the platform in Temperance Hall, and there and everywhere declaring that it ought to be sent to the hustings. But he was a convert, and the price must be paid, even though Mather Almon, who in experience and weight of character was his superior in every quality required for a legislator, should be left behind.

Of the candidates who have presented themselves for the representation of this county on the other side, it is enough to say that they are on that side, and are not the men for Galway. I would vote against my own brother if he had a hand in these transactions, or if he attempted to justify the mode in which the people of Nova Scotia have been treated. The very life and soul of any country are honour and good faith. We can never hold up our heads till we stamp out treachery, as we would the rinderpest if it came here. We would not let a plague spread among our cattle, and we must not allow our people to be contaminated with the example of these delegates. Such treason as theirs, in other countries, would earn for them the halter or axe. We may not even elevate them to the dignity of tar and feathers, but we can at least leave them on the stools of repentance to become wiser and better men.

Of the people’s candidates I need say but little. They are known to you all, as industrious, honest, business men, of shrewdness and intelligence. Mr. Cochrane and Mr. Power are universally respected by the body to which they belong, and enjoy the confidence of the community. Mr. Jones and Mr. Northup are men to whom you can safely entrust your interests at home and abroad. Mr. Balcom I have known for twenty years. I have slept beneath his roof, and know that in his domestic relations and in his commercial activity he is a fitting representative of the sturdy class of men who are enlivening the sea-coast by their industry. None of these men care for public distinctions. They would retire tomorrow, if by so doing they could serve their country. They can serve her best by fighting her battles out, and I hope to see the whole five triumphantly returned.

Howe, Joseph. Annand, William. Chisholm, Joseph Andrew. “The Speeches and Public Letters of Joseph Howe” Halifax, Canada: The Chronicle publishing company, 1909. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007688708