The local government history of Nova Scotia reflects a circuitous progression, from central control to increasing local autonomy and back again to centralized control. From its inception in 1605 with Port Royal, local governance was essentially an extension of central government, lacking elected councils or municipal institutions. Annapolis Royal saw early attempts at local government with the establishment of a civil council in 1720 and a general court in 1721. Halifax’s founding in 1749 marked a shift, with the establishment of Quarter Sessions, allowing for local governance with administrative and judicial functions. The system was influenced by both the Virginia and New England-style systems, with Quarter Sessions and an Inferior Court of Common Pleas.

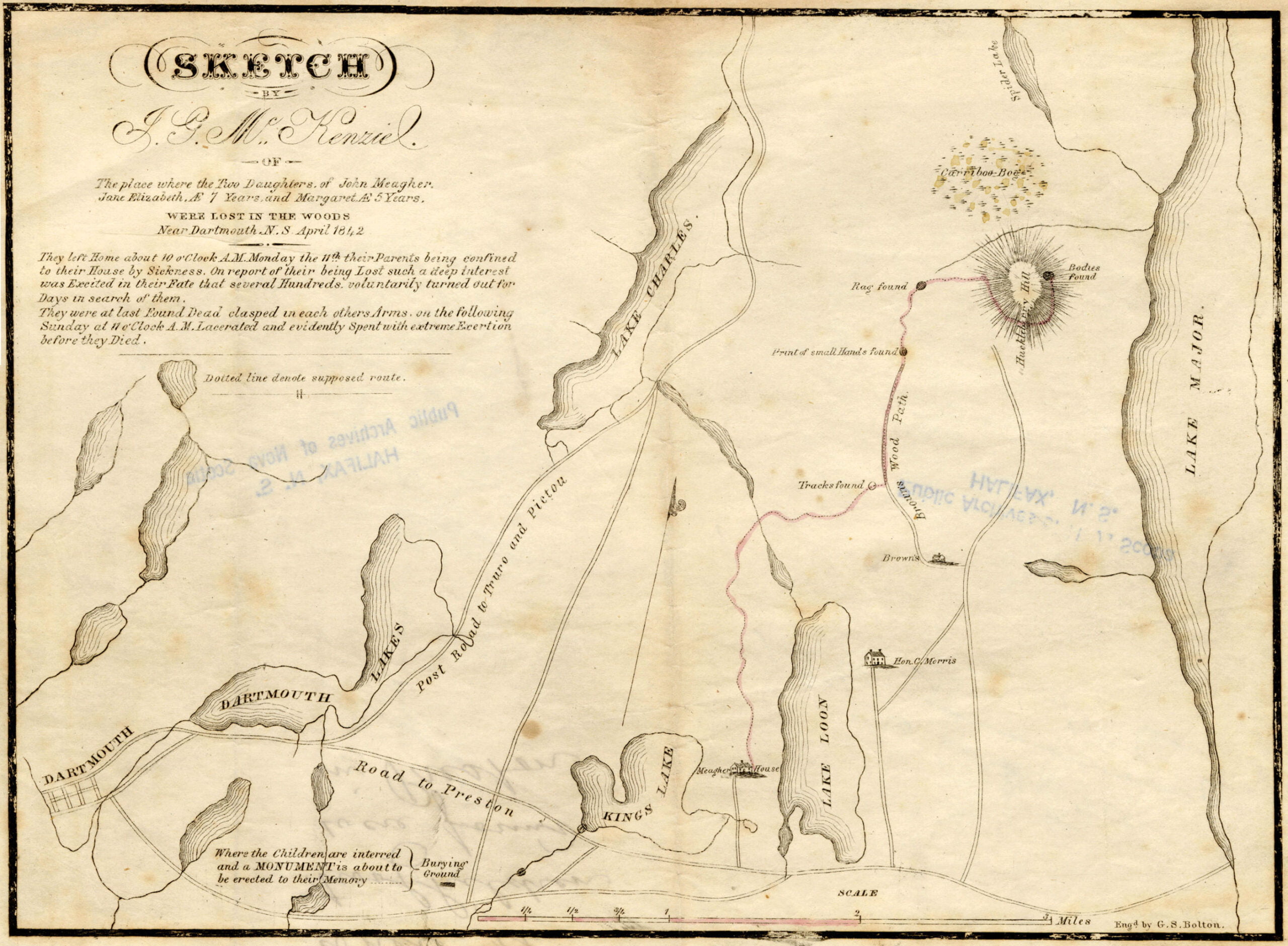

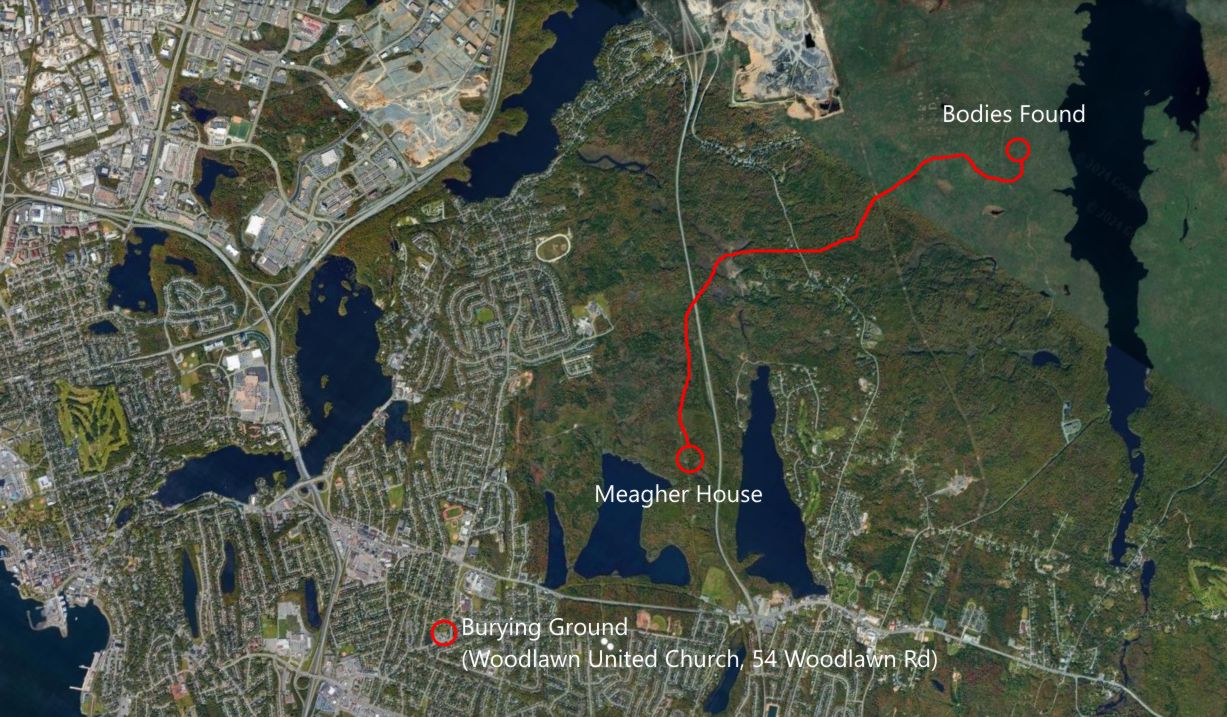

New England settlers in Halifax demanded greater local self-government, leading to conflicts and eventual incorporation of Halifax in 1841 after a push by figures like Joseph Howe. Despite earlier attempts at incorporation, Halifax faced disallowance due to resistance from the Legislative Council. Meanwhile, outside Halifax, the Quarter Sessions system persisted until 1879 when county incorporation became compulsory, replacing the old system with elected municipal councils. Towns also sought incorporation, Dartmouth being the first in 1873, with eight towns incorporated by 1888.

Towns had to meet population and area requirements for incorporation, with mayors and councillors elected for two-year terms. The councils had broad powers, including taxation and infrastructure development. By 1954, Nova Scotia comprised 18 counties, 24 rural municipalities, 39 incorporated towns, and 2 cities, each with its own local government structure, independent of county or district authority. By 1961 Dartmouth became the third incorporated city.

Functions of local government expanded over time, responding to social and economic changes. Traditional roles included regulation and service provision, such as supporting the poor, maintaining roads, and education. However, more modern demands led to the development of new services like community planning, housing, and recreation.

Financially, municipalities initially relied on property taxes but faced challenges due to increased demands and inflation. Provincial assistance, through grants and shared responsibilities, became essential, especially during times of war and economic downturns. Tax rental agreements and conditional grants help fund services like education and social assistance, reflecting a shift towards greater Provincial and Federal involvement.

Since the 1996 amalgamation, which unilaterally consolidated several local entities into one unit in a number of (what once were) counties, local government in Nova Scotia has again undergone significant restructuring. The dissolution of distinct municipalities has reshaped the landscape, upending established institutions, the concept of local government itself and the constitutional frameworks upon which it relied.

Background:

Although there were no parliamentary institutions of any kind in the area during the French regime, local government of one sort or another has existed in Nova Scotia from the founding of Port Royal in 1605. It began not with elected municipal councils, nor with incorporated towns and cities, not even with the Court of Sessions or the Quarter Sessions. In its beginning it was essentially an extension of the arm of the central government.

…central administration at Annapolis Royal was modified and a measure of local government was provided. At Annapolis Royal a civil council was established in 1720 and a general court in 1721. The Acadians continued to choose their own deputies annually; Acadians acted as collectors of quit rents, notaries, herdsmen and overseers; and one Acadian (notwithstanding the difficulty over oaths of office) was commissioned justice of the peace in 1727. At Canso from 1720 there were justices of the peace, who were also usually captains of the militia there. Moreover, during his visits to Canso, Lieutenant-Governor Armstrong gave at least a semblance of local government to the place, by consulting the justices of the peace and a committee of the people there. “the least appearance of a Civil Government:’ he wrote, “being much more agreeable to Inhabitants than that of a Martial.”

Quarter Sessions:

With the founding of Halifax by more than 2500 people from the Old Country in 1749, the seat of government was transferred to it from Annapolis Royal, and soon a system of local government by Quarter Sessions was established in the new capital. This system had been in operation in England for a long time; it was now transplanted in Nova Scotia. The Court of Quarter Sessions, composed of Justices of the Peace appointed by the Governor and Council, enabled the central government to extend its influence into local affairs. The Quarter Sessions had administrative as well as judicial functions; these included the appointment of local officers; licensing of taverns; control over weights and measures; fixing of certain prices; levying of poor and county rates; and control over roads and bridges, prisons and hospitals, and other public works.

The first Justices of the Peace for the Township of Halifax were commissioned on July 18, 1749. In December of the same year justices of the County Court were appointed, and a commission of the peace for the appointment of justices of the town and county of Halifax was issued. The justices of the County Court took their oath of office on December 27, 1749. and the County Court met for the first time on January 2, 1750. Although the first records of the Quarter Sessions are not now available (few being extant prior to 1766), it is likely that the Quarter Sessions first met on the same day as the County Court. Thus it seems quite clear that the Quarter Sessions were established at Halifax early in 1750. A year later the people were given a direct voice in choosing certain minor town officers. On January 14, 1751 the Governor and Council ordered that the town and suburbs of Halifax were to be divided into eight wards, and that the inhabitants were to be empowered annually to choose eight town overseers, one town clerk, sixteen constables and eight scavengers, for managing such prudential affairs of the town as should be committed to their care by the Governor and Council. For several years the annual election of constables was the only part of local government in which the people directly participated, and this was afterwards taken over by the Quarter Sessions.

If settlers from Old England founded Halifax, people from New England soon constituted the most important element in the new town. They quickly arrived in considerable numbers, in order to take advantage of the opportunities in trade or of the privileges accorded to settlers. Jealousy soon arose between the New World and the Old World settlers. with those from New England insisting upon a greater measure of local self-government and upon the adoption of practices to which they had previously been accustomed. At the outset the government had been modelled after that of Virginia, and accordingly, a County Court, meeting monthly, had been established. By March 2, 1752, however, a change was made in line with New England practice. The County Court became an Inferior Court of Common Pleas, meeting not monthly, but quarterly, on the first Tuesday in March, the first Tuesday in June, the first Tuesday in September, and the first Tuesday in December. As the justices of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas were also Justices of the Peace, the Quarter Sessions opened the same day as the Inferior Court, and the same Jurymen attended both courts.

For a few years, until a House of Assembly was established in 1758, the Governor and the Council of Twelve at Halifax enjoyed a monopoly of power and patronage. At the first session of the Legislature, however, the Assembly (more than half of whose members were of New England origin) initiated legislation to provide a municipal council for Halifax. Rather than agree to this bill, the Council now prepared a bill of its own for erecting Halifax into a parish, with power to provide for its own poor. A conference between the two houses was held, and a compromise seemed to be reached; yet, when the Assembly embodied this agreement in a bill for choosing town officers for the town and suburbs of Halifax and for prescribing their duty, the Council continued to procrastinate. It apparently resented the Assembly’s initiative and early in the following year it rejected the bill on the ground that it was contrary to His Majesty’s instructions. It is clear that when machinery was provided in 1759 for township government in Halifax victory lay with the Council.

Strange to say, this machinery was provided by a bill entitled “An Act for Preventing Trespasses” [extended to Dartmouth in 1818 “An act to extend the provisions of c15 of 1761 relating to Trespasses, to the Town of Pictou and the Town Plot of Dartmouth, 1818 c23“, see also “For regulating the Dartmouth Common, 1841 c52“, “An Act for Preventing Trespasses“] which was introduced in the Legislative Council and afterwards amended by the Assembly and by the Council. It empowered a joint committee of the Council and Assembly to nominate four suitable overseers of the poor, two clerks of the market, two fence viewers, two hog-reeves, and four surveyors of highways for the town of Halifax to serve until the autumn when the Grand Jury should nominate, and their Court of Sessions should appoint their successors. Thereafter annual selections were to be made in this manner. This machinery became the model for township government in Nova Scotia until 1765, when the mode of appointing town officers was modified. At that time the Grand Jury, selected by lot, was empowered to nominate two or more persons for each office, and the Court of Sessions was empowered to choose and appoint the officers from these nominees. Subsequently, in 1811, it was arranged that the number nominated was to be as the justices in sessions might direct, “as the numbers before limited by law were found insufficient.”

The New England Form of Township Government:

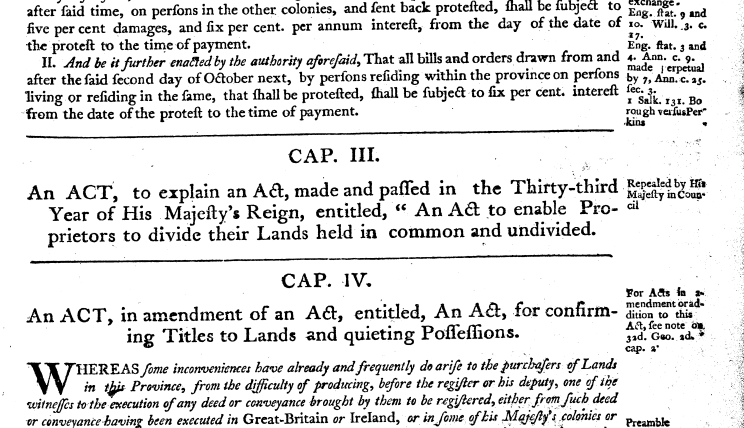

For a brief period the New England form of township government, with the direct democracy of the town meeting, was in operation in part of Nova Scotia. It was introduced at the beginning of a substantial wave of New England migration in 1760. In an attempt to fill up land recently vacated by the Acadians or never previously occupied, the authorities had promised New Englanders central and local institutions similar to their own. Between 1760 and 1765 approximately 8,000 New Englanders migrated to the agricultural townships in the Annapolis Valley, along Minas Basin and across the Isthmus of Chignecto, and to the townships for fishermen and lumbermen along the South Shore. Those who arrived in 1760, accustomed to choosing their own officers and managing their own affairs, immediately inaugurated the same sort of township government in Nova Scotia. A provincial statute was passed to enable proprietors to divide their lands, and they appointed their own committee for this purpose until His Majesty disallowed the Act in 1761. [1760 c3, “An ACT, To Explain An Act, made and passed in the Twenty Third Year of His Majesty’s Reign, entitled, “An Act to enable Proprietors to divide their lands held in common and undivided”]

The Extension of the Quarter Sessions:

The local autonomy and the direct democracy characteristic of township government in the new settlements were soon replaced by the extension of central authority and by the adoption of the principle of indirect rather than direct election. The British and Virginian way of Quarter Sessions prevailed over the New England style of township government.

In 1759 the province was divided into the five counties of Halifax, Annapolis, Kings, Lunenburg and Cumberland. Two years later, after His Majesty disallowed the act passed to enable proprietors to divide their lands, committees for that purpose were appointed by the Governor and Council. In the same year the judicial organization of Quarter Sessions and Inferior Court of Common Pleas that already existed in Halifax County was extended to Lunenburg, Kings and Annapolis Counties, and provision was made for the nomination of surveyors of highways by the Grand Jury at the General Sessions of the Peace. This mode of appointment was soon expanded to include all town officers that were chosen prior to the Act of 1765. It left the choice of the officers exclusively to the Grand Jury; but by the Act of 1765 the Grand Jury could only nominate two or more persons for each office, and then the Court of Quarter Sessions those and appointed the officers from those nominees. The central government regained control over the associated proprietors of the township by a statute prescribing that township lands could be apportioned and divided into individual shares, only after a writ had been obtained for that purpose from the Supreme Court. The provost marshal or his deputy, to whom this writ was to be addressed, had to act by inquisition of a jury in the presence of two Justices of the Peace. As new counties and districts were created, the Quarter Sessions extended into them. This system of local government by Quarter Sessions was the general mode in Nova Scotia for more than a century

Personnel In the Quarter Sessions:

In the Court of Quarter Sessions the sheriff, an appointee of the Crown, was the executive officer. Prior to 1778 there had been one provost marshal for the whole province; but thereafter there was a sheriff for each county. Until 1849 the county sheriff was chosen and appointed by the Governor and Council from a list of three names prepared by the Chief Justice or the presiding Justice. An amendment in 1849 provided for the list of three names to be made by the Chief Justice and a puisne judge for, if the Chief Justice were absent, by two puisne judges, acting with two members of the Executive Council. The Justices of the Peace were also appointed by the Crown, and they held office during the pleasure of the Crown. The Grand Jury was a select few who represented the people. It was composed of residents having freehold property of a yearly value of £10 or personal of £100. Each year the sheriff prepared a list of those qualified to serve, and at a stated time the required number of names was drawn from the box.

The Incorporation of Halifax:

[There have been at least three previous attempts to incorporate Halifax: one in 1758, as noted earlier in the Quarter Sessions section, another in 1785, and a third in 1814. However, each of these endeavors faced disallowance, either from the Legislature or the Legislative Council. In later historical accounts of Joseph Howe, one aspect that has notably been removed is his involvement in the push to incorporate Halifax. This involvement primarily revolved around his confrontation with the magistrates, which, within the framework of the existing Quarter Sessions system, represented the closest semblance to a municipal institution we would recognize today.]

Abuses crept into the system, and there were criticisms of its operation in Halifax. Grand Jury after Grand Jury attacked it; there were complaints of unfair assessment, of inefficiency and neglect in the collecting of poor, and county rates, and of other forms of maladministration. The Grand Jury appealed to the Lieutenant-Governor to remedy the situation, and he requested the House of Assembly to do so. Early in 1835 a letter signed “The People”, but written by George Thompson, charging the magistrates of Halifax with misconduct, was published by Joseph Howe in The Nova Scotian. Howe was then prosecuted for criminal libel; he defended himself in a famous trial, the outcome of which was a triumphant acquittal, establishing the freedom of the press and foreshadowing reform in local government. The cry for incorporation grew more insistent. Eventually the old system was swept from Halifax, with the incorporation of the city in 1841. By the charter of that year Halifax was endowed with municipal privileges and securities. This development in local affairs took place seven years before responsible government was won in the wider field of provincial politics in 1848.

An Interlude:

Outside the city of Halifax, the system of local government by Quarter Sessions persisted relatively undisturbed for over thirty more years. In 1850, however, there was an attempt to divide Halifax County into townships and to provide each of its townships with an elected warden and councillors, who were to assume the administrative powers previously exercised by the Justices of the Peace. But a bill to achieve these ends met the disapproval of the Colonial Secretary.

In 1855-56 two provincial statutes provided machinery for the creation of municipal government in counties desiring it by majority vote. The Act of 1855 applied to the Counties of Yarmouth, Annapolis, Kings and Queens; that of 1856 to all the other counties. These acts were permissive not compulsory. They remained on the statute book until 1879, but the fear of heavier county rates prevented any County from adopting the principle of incorporation during those years.

Another Act of 1856 permitted the voluntary incorporation of townships. The municipal council of each township was to consist of five councillors, one of whom was to be the presiding officer, under the name of town reeve. It was to have power similar to that of a county council over roads, poor relief, assessment, and other matters. Only one township-Yarmouth-took advantage of this legislation and ventured upon the experiment of municipal incorporation; and it abandoned it by a majority vote of the electors, after a three years’ trial, in 1858.

As time passed, however, the larger communities sought more amenities. In order to provide them, they began to request incorporation. Thus the towns seemed more eager than the counties to obtain the privileges of self government, and especially the privileges of assessing for local purposes and of borrowing money. Prior to 1888 eight towns were incorporated. These were Dartmouth, (1873), Pictou (1874), New Glasgow (1875), Windsor (1878), North Sydney (1885), Sydney (1885), and Kentville (1886), each of which was incorporated by special Act.

A New System: Elected Municipal Councils:

By the County Incorporation Act of 1879, the incorporation of counties was made compulsory, and the old system of local government by the Quarter Sessions was at last swept away. Its principal object was to compel the Counties to tax themselves directly to keep up their roads and bridges. It provided for the incorporation of every county and sessional district in the province. Each municipal council was to consist of a warden and councillors, with the warden being chosen by the councillors. From the enactment of this statute to 1892, councillors sat for one year; since 1892, however, their term has been three years. Six of the eighteen counties are divided into two districts, making in all twenty-four rural municipalities. These are divided into polling districts, each of which is entitled according to population to at least one representative in the council. The councils have power to assess for specified purposes, including education, the support of the poor, prevention of disease, administration of justice, court house and jail, protection from fires, and so forth.

The Towns Incorporation Act of Nova Scotia was passed in 1888, revised in 1895, and embodied in the consolidation of 1900 and the revised statutes of 1954. It requires a majority vote of the ratepayers of the town in support of incorporation before it can be granted. It also requires a certain population within a specified area-in 1954 a population of over 1500 within an area of not more than 640 acres was required for any new incorporation. A mayor and not less than six councillors are elected for each town. The mayor and councillors generally hold office for two years; but one-half of the council usually retires each year. The mayor and the councillors are eligible for re-election.

The council has power to assess, collect, and appropriate all sums of money required by the town for erecting, acquiring, improving and furnishing buildings for public schools, fire department, police office, lockups, town hall or other town purpose: streets, sewers, water, town courts, police, support of the poor, salaries, and other town purposes. It appoints town officers, excepting the stipendiary magistrate. Every part of the province is contained within a city, or a town or a rural municipality. The province is divided into eighteen counties. Twelve of the counties constitute separate municipalities; and the remaining six counties are divided into two districts or municipalities each making a total of twenty-four rural municipalities. In addition, there are thirty nine incorporated towns and three cities: Halifax (1841), Sydney (1904), and Dartmouth (1961.)

Each town or city is geographically but not politically part of a county or district, and except for joint expenditures is independent of it.

Local Government in Nova Scotia:

Local government as we know it, has arisen to meet the needs of the people. but it is something more than an agency designed to provide services and to regulate private interests for the public welfare. It has a theoretical foundation as well as a practical responsibility. It is closely linked with the democratic philosophy. Consequently it must be considered not only for its efficiency but also for its place in the democratic process. Local government contributes to the strength of democratic institutions; being close to the people it makes government more responsive to local needs and enables the citizen to participate actively in the affairs of the community. It also serves as a training ground in governmental practices and procedures for those who may later serve the province or the nation.

Structure:

The basic structure of the present system of local government in Nova Scotia must now be outlined. it rests upon the County Incorporation Act of 1879. the Towns Incorporation Act of 1888, and the special Acts by which the three cities were incorporated. It has some relationship to the earlier system of local government by Quarter Sessions, in that the Act of 1879 provided for the compulsory creation of 24 rural Municipalities, based on the boundaries of the Counties and Sessional Districts. Twelve of the eighteen Counties became separate Municipalities, while the remaining six were divided into two Municipalities each. Today there are 66 municipal units: 24 rural municipalities, 39 towns and three cities. These types of municipal units are similar in certain essentials. They are self-governing. Local matters are decided and local services are provided by elected bodies directly representative of the citizens. In addition, they have School Boards, which are chosen partly by the local Council and partly by the Governor-in-Council of the Province. But there are a number of differences. Although for administrative and electoral purposes all rural Municipalities are divided into districts, not all towns are divided into wards. Generally each district in a rural municipality elects one councillor, but some choose two, and a few return three each. In 1959 each of the 24 rural municipalities had from 4 to 24 districts, with from 8 to 26 councillors-a total of 323 districts, with 361 councillors. From late in 1961, however, the Municipality of the County of Halifax has 27 districts and 27 councillors. instead of 22 districts and 26 councillors as heretofore. Municipal councillors are elected for three-year terms.

On the other band, towns may be divided into wards (or electoral purposes, although such divisions are not compulsory. Thus, in 1959, only 11 of the 40 incorporated towns were divided into wards. According to the Towns Incorporation Act, each town must elect at least 6 councillors, each for a two-year term, with half of them retiring each year. If the town is divided into 3 wards, one councillor may be elected (rom each ward per year. Six of the towns are divided into three wards each. New Waterford, North Sydney and Sydney Mines, however, have 8 councillors and 4 wards each, while Glace Bay has 12 councillors and 6 wards. The eleventh 1959 town was Dartmouth, which then had 4 wards and 8 councillors; it has since been incorporated as a city.

Another difference is seen in the way in which Wardens and Mayors are chosen. The Warden of a Municipal Council is chosen by the councillors from among themselves, whereas the Mayor of a Town or a City is elected at large. The Mayor of Halifax, who is elected for a one-year term, may not immediately re-offer after having served for three consecutive years. The Mayor of Sydney is elected at large for a two year term, as is the Mayor of Dartmouth.

The three cities are divided into wards. Halifax now has seven wards; Sydney has six; and Dartmouth has seven. Halifax elects two aldermen for each ward on three-year terms, half being elected each year. Sydney elects a council of 12, half elected each year from six wards for a two-year term. Dartmouth has two aldermen for each of seven wards, half of them elected each year, each elected for a two-year term.

Villages may provide themselves with additional local services, administered by themselves rather than by the Municipal Council. This may be done under the Village Service Act or by special legislation, by incorporating village or service commissions for that purpose. Such villages and service commissions do not constitute separate municipal unit~; only the commissions are incorporated; and the village ratepayers still remain part of the municipality. Under the Village Service Act, the commissioners may provide street lighting, fire protection, sewers, water works. streets, roads, sidewalks, police, garbage disposal, parks, and village buildings. Service commissions incorporated by special legislation may provide fire protection, street lighting, or other services. At the end of 1960 there were 16 village commissions, incorporated under the Village Service Act, in operation, and about 20 service commissions incorporated by special Acts of the Legislature.

Within towns and cities there are a few instances of a similar nature. For example, in the City of Halifax the water utility is operated by an independent body; and in the towns of Bridgewater and Glace Bay water and electric services are provided in the same way.

The school boards of the cities, towns and municipalities are in no case elective, (except (or the. Town of Berwick,) but are appointed partly by the local councils and partly by the Governor-in-Council. Within rural municipalities prior to 1956 school trustees, incorporated, and operating for the provision of school facilities under the Education Act, had power to borrow money and to impose taxation. Since then, however, the dominant control over education in the rural municipalities has passed to the Municipal School Boards. Although school trustees still exist in the rural municipalities, they act generally only as a local agent for the Municipal School Board and they no longer have power to levy taxation or to borrow money. There are no school trustees within any town or city.

Certain joint services required by municipal and urban units-such as court houses, jails, and welfare homes, or offices for the sheriff, registrar of probate, and registrar of deeds are provided by rural municipalities for themselves and for the towns and cities within their limits. They are paid for, under a Joint Expenditure scheme, by which each unit pays a proportion of the cost.

Although each of the three cities in the province has a Mayor and a Council, Halifax has adopted a variation on the basic Mayor-Council theme, a form of the Council-Manager plan. It has not only a Mayor and a Council, but also a manager or executive director of all civic departments who is appointed by the Council.

Functions:

There has been an expansion in the functions of local government. In the old days the dominant idea was that government should only control and regulate the activities of citizens in the common interest. Two things, however, have caused substantial increases in municipal expenditures. One is the fact that social and economic changes in a rapidly moving world have created a demand not only for new services but also Cor higher and more expensive standards for those services that were previously provided by municipalities. The second is the effect of inflation upon all costs, municipal or otherwise.

The day of “the little red school house”, with one teacher for eight or ten grades, is about over. Instead we have large regional schools in central locations, costing sums of money which only a few years ago would have been regarded as astronomical, both to build and to operate, with fleets of buses to convey to school those pupils who live more than a mile or so away from it.

Another instance of the change in circumstances and in attitude is seen in the subject of transportation. The automobile and the motor truck have made paved streets desirable, if not necessary; the car driver and the truck driver of this generation regard them as necessary; the driver of the horse and wagon of the previous generation would have said that they were all very fine, but he couldn’t afford them.

Community planning, now universally regarded as necessary, is a comparatively recent development. Slum clearance and low rental housing provided by the municipality, with the co-operation of other levels of government, are now being undertaken. They were almost unheard of a few years ago.

All of these developments have created financial problems for the municipal governments. There has been an expansion of their work and of their outlay. This has resulted not only in the tax levy of Nova Scotian municipalities having been multiplied by four in less than twenty years, but also in assistance from the provincial government in two ways. One form of assistance is given by cash grants, some amounts being earmarked as direct aid for specific projects, and others being general grants without specified purposes.

The traditional functions of local government included both regulatory activities and certain services provided for citizens. Municipalities have always had a good deal to do with protecting persons and property, and the Municipal Acts all contain long lists of the specific kinds of regulation with which Councils may deal. For municipalities they range from regulating the firing of guns, the management of log booms, and the restraining of domestic fowl from going at large, to controlling brush burning, “abating all public nuisances,” and licensing “hack-men, waggoners and cart-men.” For towns and cities, they include regulating halls “for preventing accidents therein”; making building by-laws; fixing closing hours for shops; licensing restaurants and trades, gasoline pumps and swinging sign-boards; and preventing “unusual noises” and loitering. All of these regulations imply some curbing of freedom in the common interest. and failure to comply with them may involve legal proceedings and penalties. Of the traditional services the most important were the support of the poor, roads, and education.

Recent developments have produced changes even in the field of regulation, as well as in the sphere of services. There are now “truck-men” in addition to “hack-men waggoners and cart-men.” “Automatic machines” have been added to the list of licensed games. Towns and cities have had to be given power to control parking and, in many cases, to install parking meters. In general, however, the lists of kinds of regulation have remained much the same. Certain phases of law enforcement, including court houses, jails, or lock-ups, besides police and other personnel, are also the responsibility of municipalities.

If social and economic changes have affected the regulatory functions of municipal governments, they have greatly increased the demands of people and tremendously expanded the social services. The community is called upon to do many things to improve the health, the welfare and the comfort of its citizens. Local government is therefore concerned with the improvement of the social, cultural and recreational environment in a wide variety of ways. These include adult education, public libraries, traffic police for schools, public concerts and plays, auditoriums, parks and playgrounds, swimming-pools and rinks, health clinics, juvenile courts, housing and slum clearance. There is a growing consciousness of the need for community planning and for zoning. Urbanization and suburbanization, and the emergence of metropolitan areas, have their attendant problems. These raise questions as to whether they are to be dealt with by annexation, by the co-operation of two or more units in matters of mutual concern, or by other means.

Although Nova Scotia passed its first planning Act as early as 1912, municipalities for a variety of reasons proceeded slowly with the work of planning. The Act was completely revised in 1939. Amendments passed in 1956 provided for planning on a regional rather than on a strictly municipal basis. Interest in the field of planning is increasing and a beginning has been made in regional planning with the formation of three Metropolitan Planning Commissions (to August 31,1961). These are (1) the Richmond Inverness Metropolitan Planning Commission, including the Town of Port Hawkesbury and the adjoining southern portion of Richmond and Inverness Counties; (2) the East River Valley Planning Commission, including the Towns of New Glasgow, Stellarton Trenton and Westville, and the adjoining area of the County of Pictou; and (3) the North Side Metropolitan Planning Commission, including the Towns of North Sydney and Sydney Mines and the adjoining area of the County of Cape Breton. Subdivision regulations to enable better control by Planning Boards over subdividing have been enacted for eleven municipal units. The number of municipal units having zoning by-laws is increasing. In the field of housing and urban redevelopment, the City of Halifax began construction of low rental housing about ten years ago, and it has recently completed a survey for slum clearance and embarked upon this project.

Finance:

When municipalities were created, they were obliged to collect money to pay for the services which they provided, including roads and bridges, education and the support of the poor. For those purposes they had to resort to the direct taxation of real and personal property. It was their aversion to this sort of taxation which delayed the establishment of municipal self-government.

For some time there was criticism of the new system in some of the municipalities. But generally they seemed to get along fairly well with the revenue from taxation on real and personal property. The services they provided were neither elaborate nor expensive, though they were reasonably adequate for the demands of the day. By the County Incorporation Act of 1879 the management of the road and bridge service was transferred to the municipal councils instituted by the Act. At that time the Provincial Government reduced its expenditure on this service and left it up to the new municipal councils to maintain the former standards by supplementing that amount out of their own revenues. Eventually this dual control proved impracticable; in 1907 the Province reassumed the expenditure of all provincial moneys for roads. For another ten years the municipal councils continued to look after the statute labour on the highways, and then they lost that control when this was ended. The coming of the automobile had created the need for change. Greatly improved highways were necessary, and the Province began to assume responsibility for this service. At the outset the Province asked the rural municipalities to make a contribution towards the cost of highways based on a fixed rate of taxation on their assessments. This provided about $250,000. In 1961, however, for highways of the standard now in existence the Legislature has appropriated $15,000,000 for maintenance and improvement, to be raised by taxation, and an additional $16,000,000 for construction, to be raised by borrowing.

If the coming of the automobile caused a change, other changes were made by the depression of the thirties and by the second World War. The depression led to a greater measure of planned regulation and to a continuing drive for a more adequate system of social services. During the war municipalities did very little in the way of capital construction or expansion of services. It would have been regarded as unpatriotic to enter the money market to borrow money j that was left for the Dominion in order to ensure necessary financing for the war. It would also have been regarded as unpatriotic to enter the labour market or to purchase material; those also were reserved for war purposes. Consequently, when the war ended municipalities found it necessary to undertake the immediate replacement of some of their capital assets. The attitude of people had also changed. No longer were they satisfied with the type of service previously provided by municipalities; they now wanted better services sometimes much better services, and handsomer buildings, including finer buildings to accommodate a larger school population. They wanted all the streets in the municipality to be paved. With the construction of many new houses, there was also a corresponding increase in the demand for water, sewer and other services which these require.

Along with new demands went higher costs. Inflation had arrived, and seemed to be here to stay. Everything the municipalities bought or built cost a great deal more than it would have cost before the war. But if costs had changed, so had the attitude of the people. All this meant that the municipalities had to provide increasingly large sums of money, and they declared that they were unable to do so from the traditional taxes on real and personal property. If these services were to be provided then the Provincial or the Federal Government would have to help.

Even earlier, as we have seen, the Province had assumed responsibility for highways. There had also been increasing Provincial participation in school administration from 1864-65, when a free school system, supported by compulsory assessment, bad been established in Nova Scotia. Estimates for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1962 require the Province to pay over $23,000,000 towards the cost of education.

The system of unconditional or unspecified grants made by the Province to the municipalities is of quite recent origin. It also arose during and because of the war. Prior to 1942 the municipalities had the right to levy a tax on income, though it had not been used a great deal in Nova Scotia. Then as the Dominion required large sums of money for war purposes, an agreement was made in 1942 between the Province and the Dominion, under which the Province for itself and for the municipalities withdrew from the income tax field so as to leave it to the Dominion alone. This was the first of what are sometimes called “tax rental agreements.” Under that 1942 agreement, the Dominion made certain payments to the Province. In order to compensate the municipalities for their potential loss because the income tax had been taken from them, the Province made cert.1.in grants to them. The major part of the grants now being paid by the Province to its cities, towns and rural municipalities is based on population. The total of these grants for 1961 is approximately $1,000,000.

Grants for specified purposes are also being paid by the Province to the municipalities in a number of fields. Those for education have already been mentioned. Another example is social assistance (formerly called “poor relief”) in which the Province and the Dominion together pay a total of two-thirds of the cost, provided certain standards are met and certain specifications are followed. Similar assistance is made to the county homes, as long as the stipulated standards are maintained. In the operation of county mental hospitals (formerly called “local asylums”), the Province pays one-half the cost, if the required standards are met. The public health scheme under which free hospital care is now provided to the general public has relieved the municipal units of practically their entire expenditure for this purpose.

Notwithstanding the greatly increased participation by the Province in these services, the municipalities have also expended increasingly large sums upon them. Their disbursements on education rose from a little over $3,000,000 in 1943 to a net total of approximately $16,600,000 in 1959. Their total tax levy increased from $8,306,543 in 1942 to $13,620,650 in 1949, and then to $31,626,165 in 1959. Their total general revenue, excluding joint expenditure boards and district or area rates, was $41,560,135 in 1959. Of that amount, about $31,000,000 was raised by taxation, while sums of $2,132,245 and $3,530,607 were received from the Federal and Provincial Governments, respectively.

It is clear, from the increased levy by the municipalities and from the increased participation by the Province and the Dominion, that the cost of providing the public with what were formerly known as municipal services has shown a very great increase indeed.

“Local Government in Nova Scotia”, Fergusson, C. Bruce. 1961. The Institute of Public Affairs, Dalhousie University. https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/handle/10222/11024