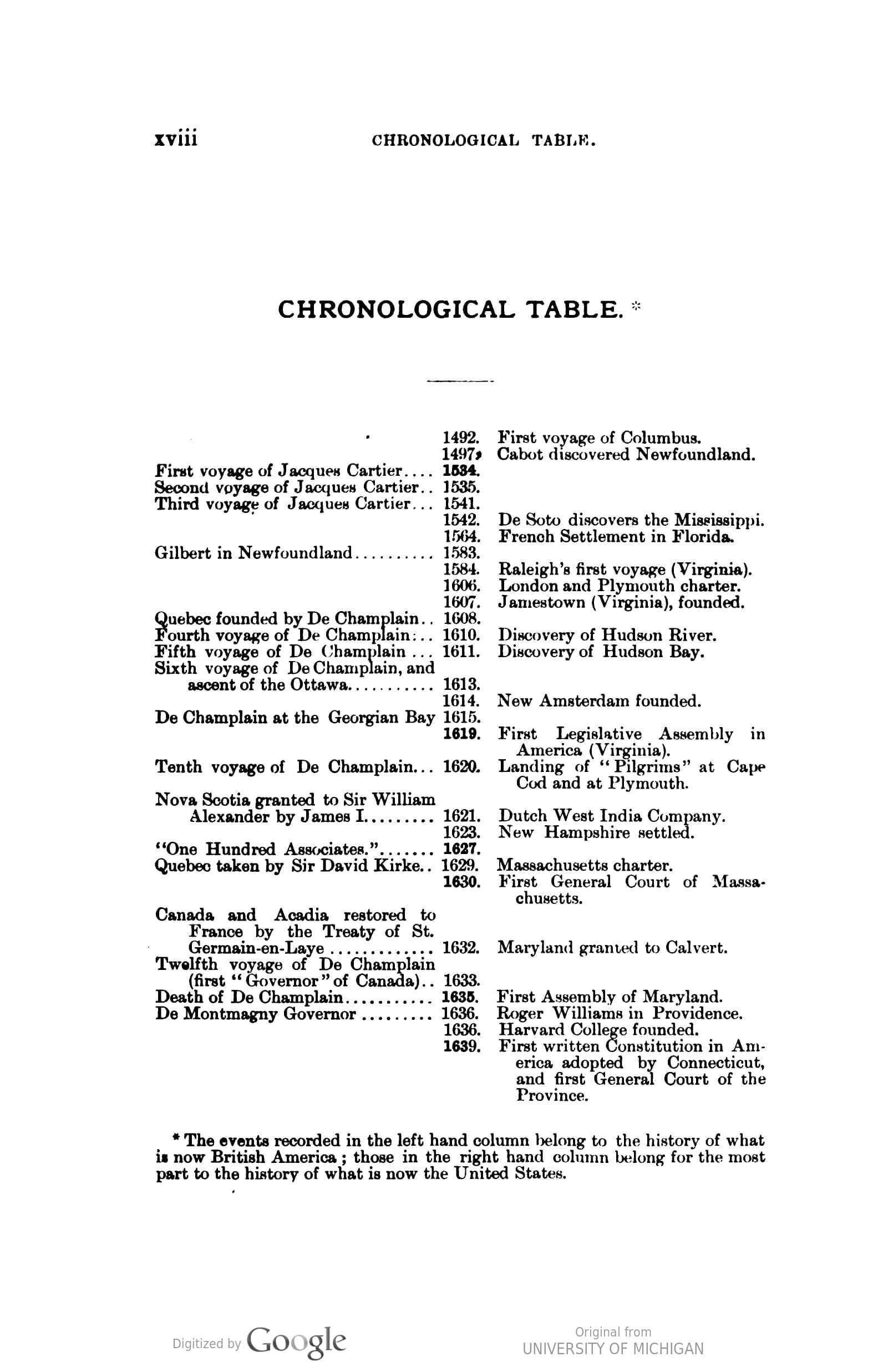

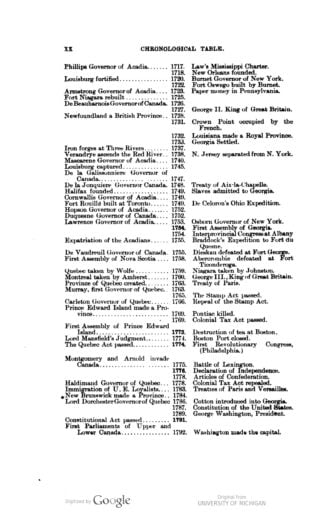

“The events recorded in the left hand column belong to the history of what is now British America; those in the right hand column belong for the most part to this history of what is now the United States:

| 1492 | First Voyage of Columbus | |

| 1497 | Cabot discovered Newfoundland | |

| First Voyage of Jacques Cartier | 1534 | |

| Second Voyage of Jacques Cartier | 1535 | |

| Third Voyage of Jacques Cartier | 1541 | |

| 1542 | De Soto discovers the Mississippi | |

| 1564 | French settlement in Florida | |

| Gilbert in Newfoundland | 1583 | |

| 1584 | Raleigh’s first voyage (Virginia) | |

| 1606 | London and Plymouth charter | |

| 1607 | Jamestown (Virginia), founded | |

| Quebec founded by De Champlain | 1608 | |

| Fourth voyage of De Champlain | 1610 | Discovery of Hudson River |

| Fifth voyage of De Champlain | 1611 | Discovery of Hudson Bay |

| Sixth voyage of De Champlain, and ascent of the Ottawa | 1613 | |

| 1614 | New Amsterdam founded | |

| De Champlain at the Georgian Bay | 1615 | |

| 1619 | First Legislative Assembly in America (Virginia) | |

| Tenth voyage of De Champlain | 1620 | Landing of “Pilgraims” at Cape Cod and at Plymouth |

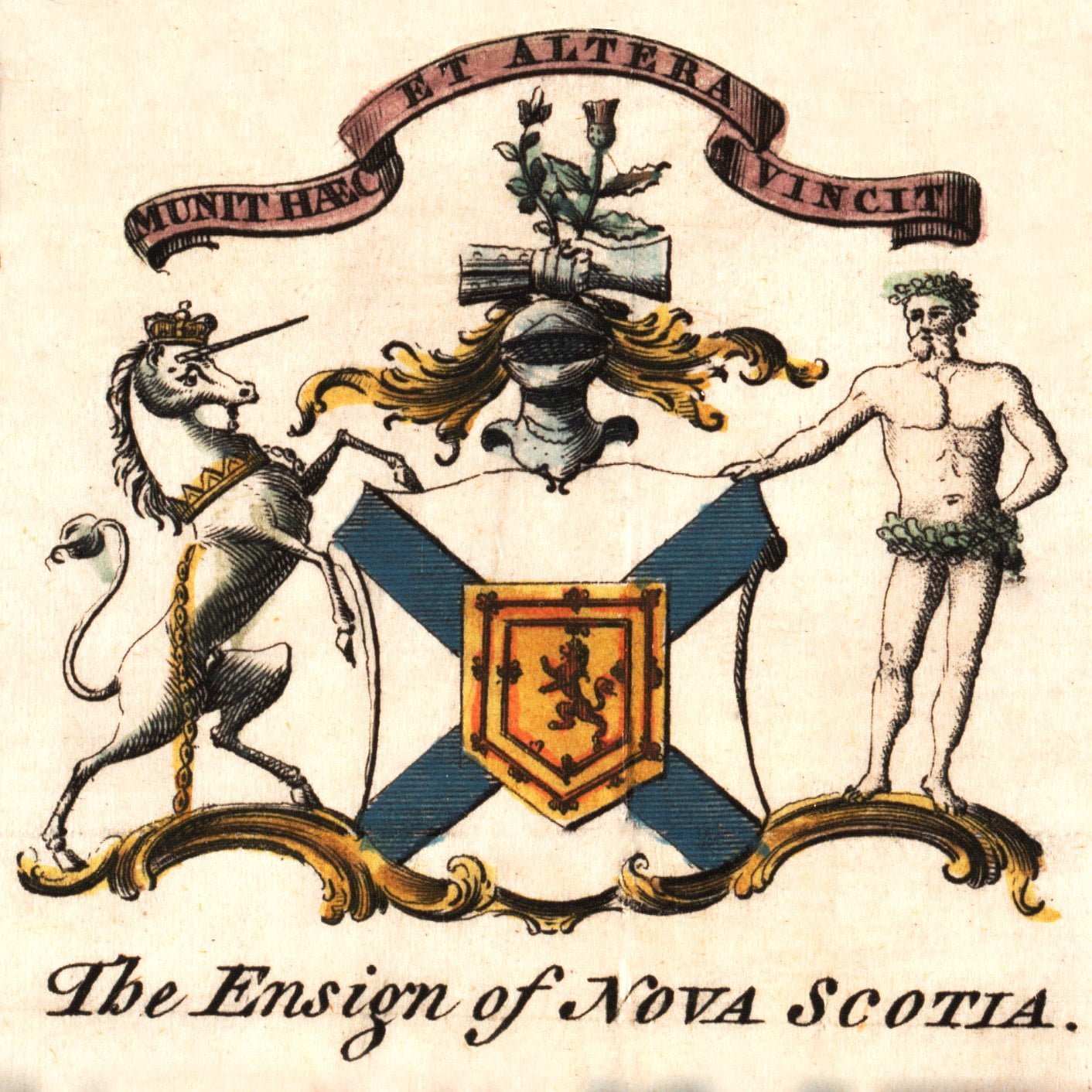

| Nova Scotia granted to Sir William Alexander by James I | 1621 | Dutch West India Company |

| 1623 | New Hampshire settled | |

| “One Hundred Associates” | 1627 | |

| Quebec taken by Sir David Kirke | 1629 | Massachusetts charter |

| 1630 | First General Court of Massachusetts | |

| Canada and Acadia restored to France by the Treaty of St. Germain-en-Lye | 1632 | Maryland granted to Calvert |

| Twelfth voyage of De Champlain (first “Governor” of Canada) | 1633 | |

| Death of De Champlain | 1635 | First Assembly of Maryland |

| De Montmagny Governor [of Canada] | 1636 | Roger Williams in Providence |

| 1636 | Harvard College formed | |

| 1639 | First written constitution in America adopted by Connecticut, and first General Court of the Province | |

| Settlement of Montreal | 1642 | Charter granted to Rhode Island |

| 1643 | New England Confederacy | |

| D’Ailleboust, Governor of Canada | 1648 | Treaty of Westphalia |

| De Lauson, Governor [of Canada] | 1651 | |

| 1652 | Maine annexed to Massachusetts | |

| D’Argenson, Governor [of Canada] | 1658 | Indian war at Esopus |

| Bishop Laval at Quebec | 1659 | Quakers hanged at Boston |

| D’Avangour, Governor [of Canada] | 1660 | |

| Colbert, Prime Minister of France | 1661 | |

| 1662 | Charter granted to Connecticut | |

| “Sovereign Council” established with De Mesy as Governor of “New France” | 1663 | Rhode Island charter |

| Seminary of St. Sulpice acquire Montreal | 1663 | |

| De Tracy Viceroy, and De Courcelles Governor [of Canada] | 1664 | New York taken by the British |

| West India Company granted Monopoly of Canadian trade | 1664 | Connecticut and New Haven united |

| Iroquois country invaded | 1666 | |

| Bay of Quinte Seminary mission | 1668 | First Assembly of New Jersey |

| 1669 | First Assembly of North Carolina | |

| Hudson Bay Company chartered | 1670 | Charleston South Carolina founded |

| 1672 | ||

| 1673 | Mississippi discovered by Joliet and Marquette | |

| Laval Bishop of Quebec | 1674 | First Assembly of South Carolina |

| De la Salle visits France | 1674 | New Netherlands (New York), New Jersey and Delaware ceded to Britain by Holland |

| Reduction of tithe to one-twenty-sixth | 1679 | First Assembly in New Hampshire |

| Indian Council at Montreal | 1680 | De la Salle on the Illinois |

| De la Barre Governor [of Canada] | 1682 | Penn founds Pennsylvania |

| 1682 | De la Salle descends the Mississippi | |

| 1684 | The Mississippi Company established | |

| De Denonville Governor [of Canada] | 1685 | |

| Hudson Bay forts taken | 1686 | Andros Governor of Massachusetts |

| Departure of Bishop Laval | 1688 | New York annexed to New England |

| Massacre of Lachine | 1689 | William III King of England |

| De Frontenac Governor [of Canada] | 1689 | Andros expelled from Massachusetts |

| Quebec attacked by Phips | 1690 | New Hampshire annexed to Massachusetts |

| 1697 | Treaty of Ryswick | |

| Death of De Frontenac | 1698 | |

| De Calieres Governor [of Canada] | 1699 | Penn visits America |

| Indian Treaty of Peace (Montreal) | 1701 | New charter for Pennsylvania |

| 1702 | War of Spanish succession | |

| De Vaudreuil Governor [of Canada] | 1703 | |

| “Superior Council” created | 1703 | |

| Capture of Port Royal (Annapolis) [Nova Scotia] | 1710 | Hunter Governor of New York |

| Expedition of Walker and Hill against Quebec | 1711 | |

| 1712 | Crozat’s Mississippi Charter | |

| 1713 | Treaty of Utrecht | |

| Nicholson Governor of [Nova Scotia] | 1714 | George I, King of Great Britain |

| Death of Louis XIV | 1715 | |

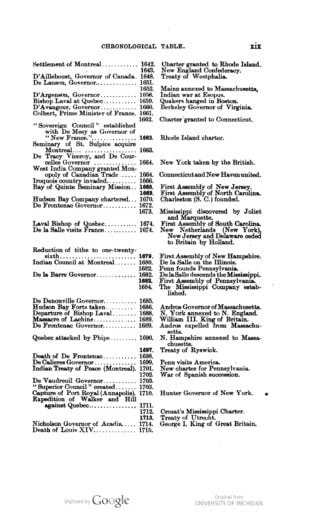

| Phillips Governor of [Nova Scotia] | 1717 | Law’s Mississippi charter |

| 1718 | New Orlean’s founded | |

| Louisburg fortified | 1720 | Burnet Governor by New York |

| 1722 | Fort Oswego built by Burnet | |

| Armstrong governor of [Nova Scotia] | 1723 | Paper money in Pennsylvania |

| Fort Niagara rebuilt | 1725 | |

| De Beauharnois Governor of Canada | 1726 | |

| 1727 | George II King of England | |

| Newfoundland a British Province | 1728 | |

| 1731 | Crown Point occupied by the French | |

| 1732 | Louisiana made a Royal Province | |

| 1733 | Georgia Settled | |

| Iron forges at Three Rivers | 1737 | |

| Verandrye ascends the Red River | 1738 | New Jersey separated from New York |

| Mascarene Governor of [Nova Scotia] | 1740 | |

| Louisburg captured | 1745 | |

| De la Galissonniere Governor of Canada | 1747 | |

| De la Jonquiere Governor of Canada | 1748 | Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle |

| Halifax [Nova Scotia] founded | 1749 | Slaves admitted to Georgia |

| Cornwallis Governor of [Nova Scotia] | 1749 | |

| Fort Rouille built at Toronto | 1749 | De Celeron’s Ohio expedition |

| Hopson governor of [Nova Scotia] | 1752 | |

| Duquesne Governor of Canada | 1752 | |

| Lawrence Governor of [Nova Scotia] | 1753 | Osborn Governor of New York |

| 1754 | First Assembly of Georgia | |

| 1754 | Interprovincial Congress at Albany | |

| Expatriation of the Acadians | 1755 | Braddock’s Expedition to Fort du Quense |

| De Vaudreuil Governor of Canada | 1755 | Dieskau defeated at Fort George |

| First Assembly of Nova Scotia | 1758 | Abercrombie defeated at Fort Ticonderoga |

| Quebec taken by Wolfe | 1759 | Niagara taken by Johnston |

| Montreal taken by Amherst | 1760 | George III, King of Great Britain |

| Province of Quebec created | 1763 | Treaty of Paris |

| 1763 | ||

| 1765 | The Stamp Act passed | |

| Carleton Governor of Quebec | 1766 | Repeal of the Stamp Act |

| Prince Edward Island made a Province | 1769 | Pontiac killed |

| 1769 | Colonial Tax Act passed | |

| First Assembly of Prince Edward Island | 1773 | Destruction of tea at Boston |

| Lord Mansfield’s judgement | 1774 | Boston port closed |

| The Quebec Act passed | 1774 | First Revolutionary Congress, (Philadelphia) |

| Montgomery and Arnold invade Canada | 1775 | Battle of Lexington |

| 1776 | Declaration of Independence | |

| Haldimand Governor of Quebec | 1778 | Articles of Confederation |

| 1778 | Colonial Tax Act repealed | |

| Immigration of United Empire loyalists | 1783 | Treaties of Paris and Versailles |

| New Brunswick made a Province | 1784 | |

| Lord Dorchester Governor of Quebec | 1786 | Cotton introduced into Georgia |

| 1787 | Constitution of the United States | |

| 1789 | George Washington, President | |

| Constitutional Act passed | 1791 | |

| First Parliaments of Upper and Lower Canada | 1792 | Washington made the capital |

| 1794 | The Jay Treaty (London) | |

| Prescott Governor of Canada | 1796 | Washington’s retirement |

| Second Parliament of Upper Canada (York) | 1797 | John Adams, President |

| 1801 | Thomas Jefferson, President | |

| Selkirk’s Colony in Prince Edward Island | 1803 | Louisiana ceded by France |

| Craig Governor of Canada | 1806 | Lewis and Clark reach the Pacific |

| 1809 | James Madison, President | |

| Prevost Governor of Canada | 1811 | |

| Selkirk’s settlers at Red River | 1812 | War declared against Britain |

| 1814 | Treaty of Ghent | |

| Sherbrooke Governor of Canada | 1816 | |

| 1817 | James Monroe, President | |

| Richmond Governor of Canada | 1818 | Convention of London |

| 1819 | Florida purchased from Spain | |

| Dalhousie Governor of Canada | 1820 | Maine admitted as a State |

| Cape Breton annexed to Nova Scotia | 1820 | Missouri compromise |

| 1825 | John Quincy Adams, President | |

| Canada Company formed | 1826 | |

| 1829 | Andrew Jackson, President | |

| Aylmer Governor of Canada | 1830 | First railway in the United States |

| Revenue Control Act | 1831 | |

| First Assembly in Newfoundland | 1832 | |

| Gosford Governor of Canada | 1835 | |

| 1837 | Victoria Queen of Britain | |

| Rebellion in Canada | 1837 | Martin Van Buren, President |

| Lower Canadian Constitution Suspended | 1838 | |

| Durham Governor of British America | 1838 | |

| Sydenham Governor of the Canadas | 1839 | |

| Union Act | 1840 | |

| Sydenham Governor of Canada | 1841 | William H. Harrison, President |

| First Parliament of Canada | 1841 | John Tyler, President |

| Responsible Government introduced | 1842 | |

| Bagot Governor of Canada | 1842 | Ashburn Treaty (Washington) |

| Matcalfe Governor of Canada | 1843 | |

| Great fire in Quebec City | 1845 | James Knox Polk, President |

| Elgin Governor of Canada | 1846 | War with Mexico |

| 1848 | Treaty with Mexico | |

| Rebellion losses agitation | 1849 | Zachary Taylor, President |

| 1850 | Willard Filmore, President | |

| 1850 | Fugitive Slave Bill | |

| Gavazzi Riots in Montreal | 1853 | Franklin Pierce, President |

| Clergy Reserves secularized | 1854 | Reciprocity Treaty (Washington) |

| Feudal tenure abolished | 1854 | Kansas-Nebraska Bill passed |

| Head Governor of Canada | 1855 | Kansas riots |

| 1857 | James Buchanan, President | |

| 1857 | “Dred Scot” case | |

| Canadian Federation mooted | 1859 | Harper’s Ferry uprising |

| The Anderson (fugitive slave) case | 1860 | |

| Monck Governor of Canada | 1861 | War of Secession begun |

| 1861 | Abraham Lincoln, President | |

| Self governing Colonies made responsible for their own defence | 1862 | The Alabama sails from Liverpool |

| Colonial Habeas Corpus Act | 1862 | |

| Quebec Conference | 1864 | |

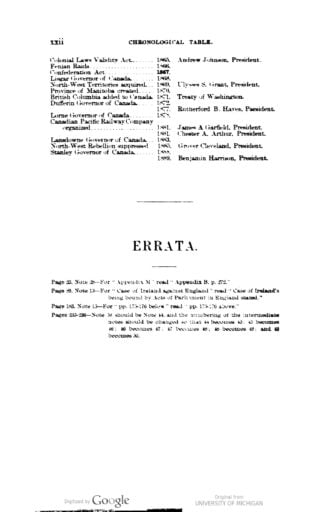

| Colonial Laws Validity Act | 1865 | Andrew Johnson, President |

| Fenian Raids | 1866 | |

| Confederation Act | 1867 | |

| Lisgar Governor of Canada | 1868 | |

| Northwest Territories acquired | 1869 | Ulysses S. Grant, President |

| Province of Manitoba | 1870 | |

| British Columbia added to Canada | 1871 | Treaty of Washington |

| Dufferin Governor of Canada | 1872 | |

| 1877 | Rutherford B. Hayes, President | |

| Lorne Governor of Canada | 1878 | |

| Canadian Pacific Railway organized | 1881 | James A. Garfield, President |

| 1881 | Chester A. Arthur, President | |

| Landowne Governor of Canada | 1883 | |

| Northwest rebellion suppressed | 1885 | Grover Cleveland, President |

| Stanley Governor of Canada | 1888 | |

| 1889 | Benjamin Harrison, President |

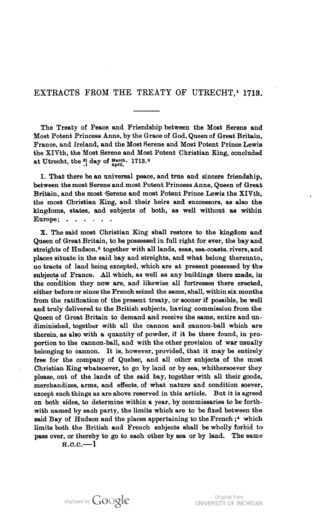

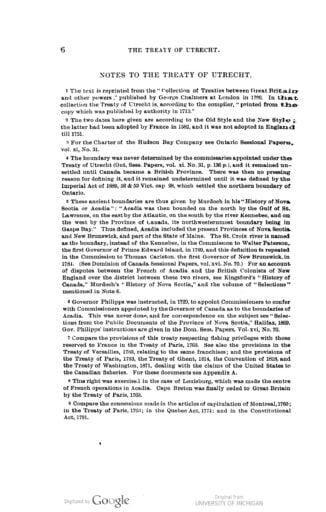

“NOTES TO THE TREATY OF UTRECHT:

- The text is reprinted from the “ Collection of Treaties between Great Britain and other powers,” published by George Chalmers at London in 1790. In that collection the Treaty of Utrecht is, according to the compiler, “printed from the copy which was published by authority in 1713.”

- The two dates here given are according to the Old Style and the New Style ; the latter had been adopted by France in 1582, and it was not adopted in England till 1751.

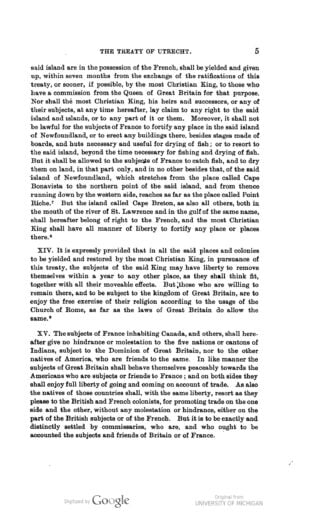

- For the Charter of the Hudson Bay Company see Ontario Sessional Papers, vol, xi, No. 31.

- The boundary was never determined by the commissaries appointed under the Treaty of Utrecht (Ont, Sess. Papers, vol. xi. No. 31, p. 136 p.), and it remained un- settled until Canada became a British Province. There was then no pressing reason for defining it, and it remained undetermined until it was defined by the Imperial Act of 1889, 52 & 53 Vict. cap 28, which settled the northern boundary of Ontario.

- These ancient boundaries are thus given by Murdoch in his “History of Nova Scotia or Acadia”: “Acadia was then bounded on the north by the Gulf of St. Lawrence, on the east by the Atlantic, on the south by the river Kennebec, and on the west by the Province of Canada, its northwesternmost boundary being in Gaspe Bay.” Thus defined, Acadia included the present Provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and part of the State of Maine. The St. Croix river is named as the boundary, instead of the Kennebec, in the Commission to Walter Paterson. Prince Edward Island, in 1769, and this definition is repeated in the Commission to Thomas Carleton. the first Governor of New Brunswick, in 1781. (See Dominion of Canada Sessional Papers, vol. xvi. No. 70.) For an account of disputes between the French of Acadia and the British Colonists of New England over the district between these two rivers, see Kingsford’s “History of Canada,” Murdoch’s “ History of Nova Scotia,” and the volume of “Selections” mentioned in Note 6.

- Governor Philipps was instructed, in 1729, to appoint Commissioners to confer with Commissioners appointed by the Governor of Canada as to the boundaries of Acadia. This was never done, and for correspondence on the subject see “Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia,” Halifax, 1869. Gov. Philipps’ instructions are given in the Dom. Sess. Papers, Vol. xvi, No. 70.

- Compare the provisions of this treaty respecting fishing privileges with those reserved to France in the Treaty of Paris, 1763. See also the provisions in the Treaty of Versailles, 1783, relating to the same franchises; and the provisions of the Treaty of Paris, 1783, the Treaty of Ghent, 1814, the Convention of 1818, and the Treaty of Washington, 1871, dealing with the claims of the United States to the Canadian fisheries. For these documents see Appendix A.

- This right was exercised in the case of Louisburg, which was made the centre of French operations in Acadia. Cape Breton was finally ceded to Great Britain by the Treaty of Paris, 1763.

- Compare the concessions made in the articles of capitulation of Montreal, 1760; in the Treaty of Paris, 1763; in the Quebec Act, 1774; and in the Constitutional. Act, 1791.”

Houston, William. “Documents illustrative of the Canadian constitution” Toronto : Carswell, 1891″ https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001144305