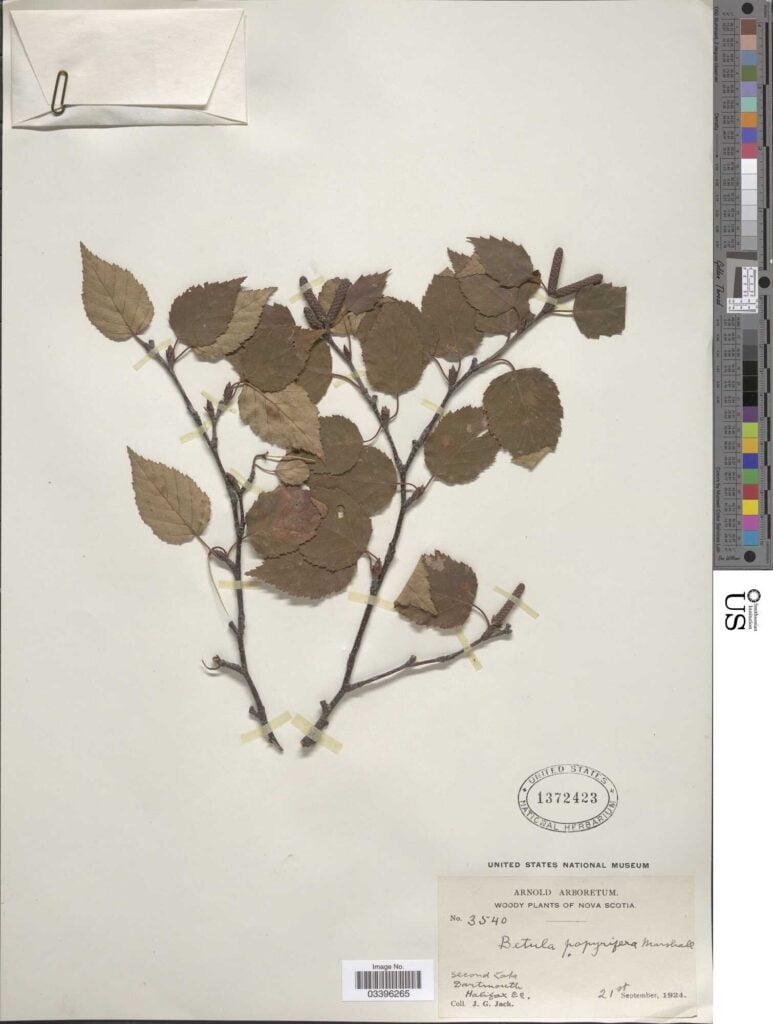

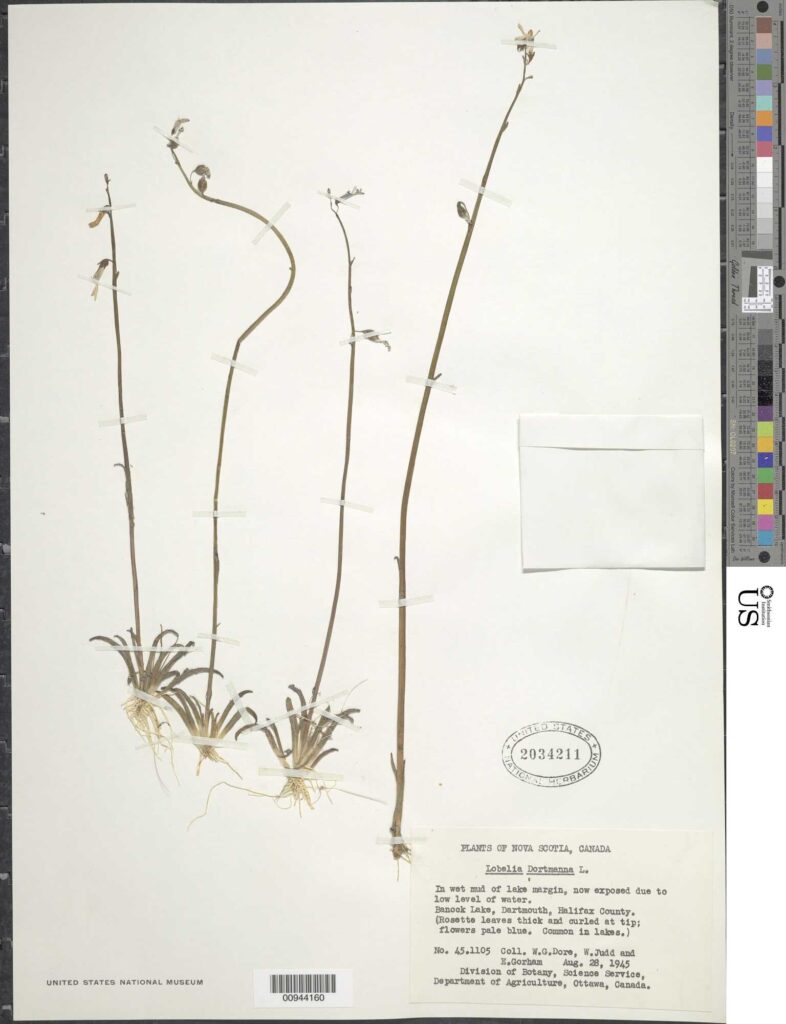

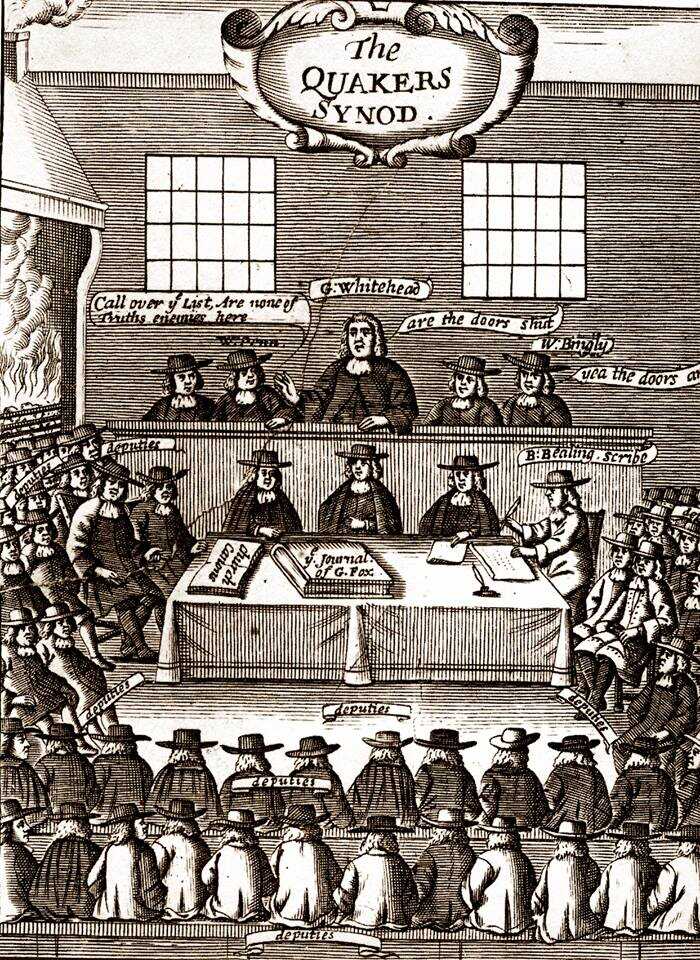

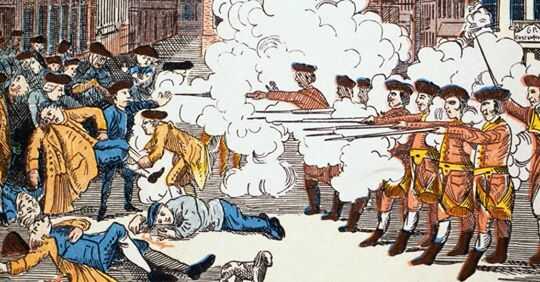

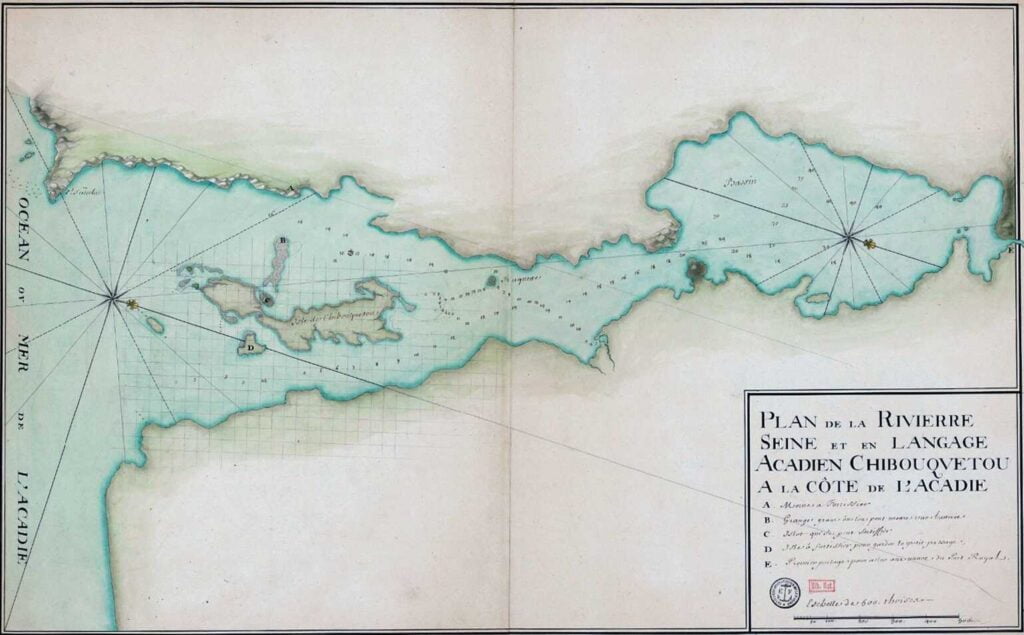

Our couriers between Quebec and Montreal depart from hence twice a week. The letters they carry scarce defray the expense of the riding work; but, seeing that the conveniency of the posts weekly is felt by the mercantile body, and in short by the whole province, and saves the expense of many expresses to Government, I shall continue it as long as it does not bring the office in debt. In all probability we shall be shut out from all communications from any one part of the world after the middle of November until the middle of May, unless letters can be conveyed from the station of the packet-boat (wherever that may be) to Halifax, in Nova Scotia, there to be put under Governor Legge’s care. He could find some trusty [Mi’kmaq] or Acadians to carry a mail across to Quebec, but as (’tis said) there’s many Whigs (as they are called) in Nova Scotia, great caution should be used by the couriers. I cannot see any other method for the Government despatches than the following, laid before General Gage. The couriers will cross over from the River des Loups to the Lake Timisquata on the height of land, then down the River Madawaska to St. John’s River, following its stream to its mouth. This route is practicable in all seasons, though difficult in the fall and early in the spring. Couriers may be despatched from Quebec. A trusty person at the mouth of St. John’s will receive all despatches from Canada or Halifax. The Canadian couriers will leave their packets there, and will take up those for Canada; the expresses from Halifax will carry back the packets from Quebec.

“George III: September 1775.” Calendar of Home Office Papers (George III): 1773-5. Ed. Richard Arthur Roberts. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1899. 397-422. British History Online. Web. 2 April 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/home-office-geo3/1773-5/pp397-422.