According to Harry Piers’ pamphlet on early blockhouses, the timber for the one at Dartmouth was prepared in Halifax. Governor Cornwallis employed French inhabitants squaring logs for that purpose during the winter of 1749-1750. The first mention of ours, is on February 23, 1751, when the Governor orders a “Sergeant and ten or twelve men of the military of Dartmouth, should mount guard at night in the blockhouse, and that they should be visited from time to time by the lieutenant”.

But the blockhouse evidently did not afford much protection when the testing time came. The Alderney settlers had been here about eight months when they suffered a terrifying catastrophe. One night in May of 1751, a ferocious band of [Mi’kmaq] swooped down on the village, and brutally butchered the helpless inhabitants. The frantic screams of the victims could be heard in Halifax. Akins’ History says that Captain Clapham and his Rangers remained inside the blockhouse, firing through the loopholes during the whole affair.

The subsequent report of Governor Cornwallis gives four people killed and six taken prisoners. Private letters written from Halifax, and published in a London paper that summer, increase the number to eight. Another narrative states that the “[Mi’kmaq] massacred several of the soldiery and inhabitants, sparing neither women nor children. A little baby was found lying by its parents, all three scalped. The whole town was a scene of butchery, some having their hands cut off, their bellies ripped open, and others with their brains dashed out.”

Captain Moorsom’s description of Nova Scotia written in 1828, states that almost the whole number of the settlers were destroyed and only one or two escaped. At the time there was an old resident of Halifax who had been a child at the time of the Dartmouth massacre. When the [Mi’kmaq] rushed into his father’s cottage and tomahawked his parents, he escaped their fury by hiding under the bed.

One result of the 1751 massacre was that a wooden wall was soon afterwards erected around the vulnerable sides of the town-plot, the same as had been done in Halifax. Mr. Piers in his writings, explains that these palisades or stockades consisted of stout trees, each six inches in diameter and about ten feet long, of which three feet were firmly embedded in the ground with the lower and upper parts spiked to a stringer. Their tops were sharply pointed in order to add to the difficulty of scaling.

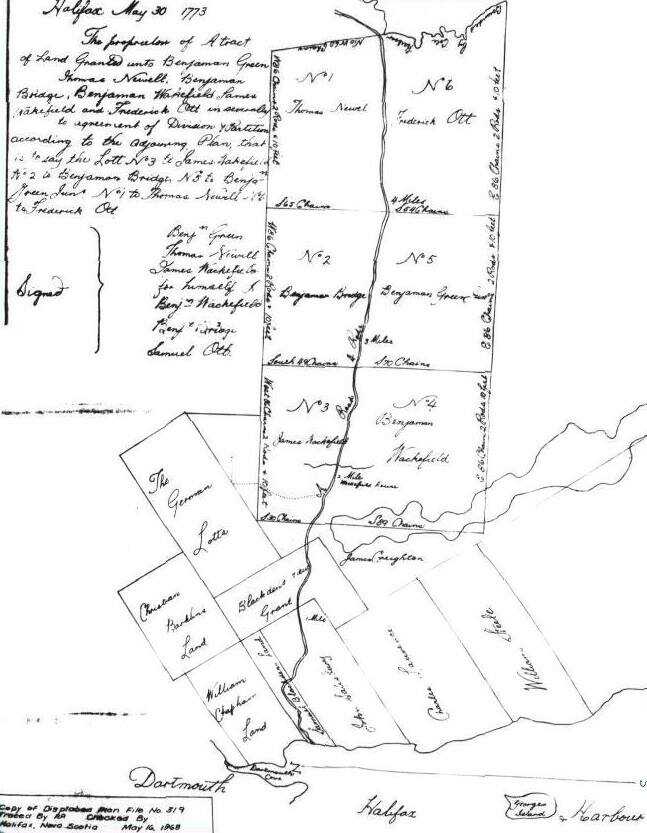

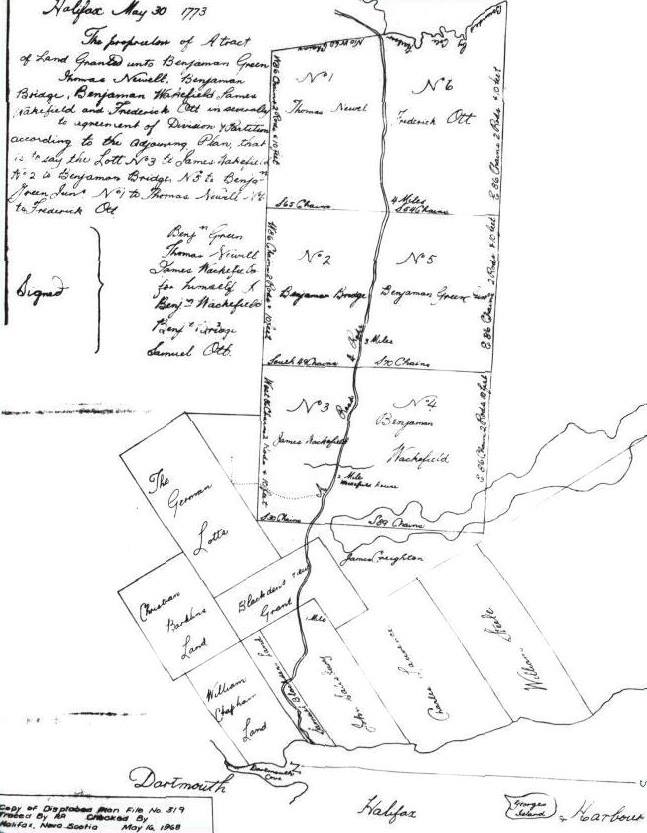

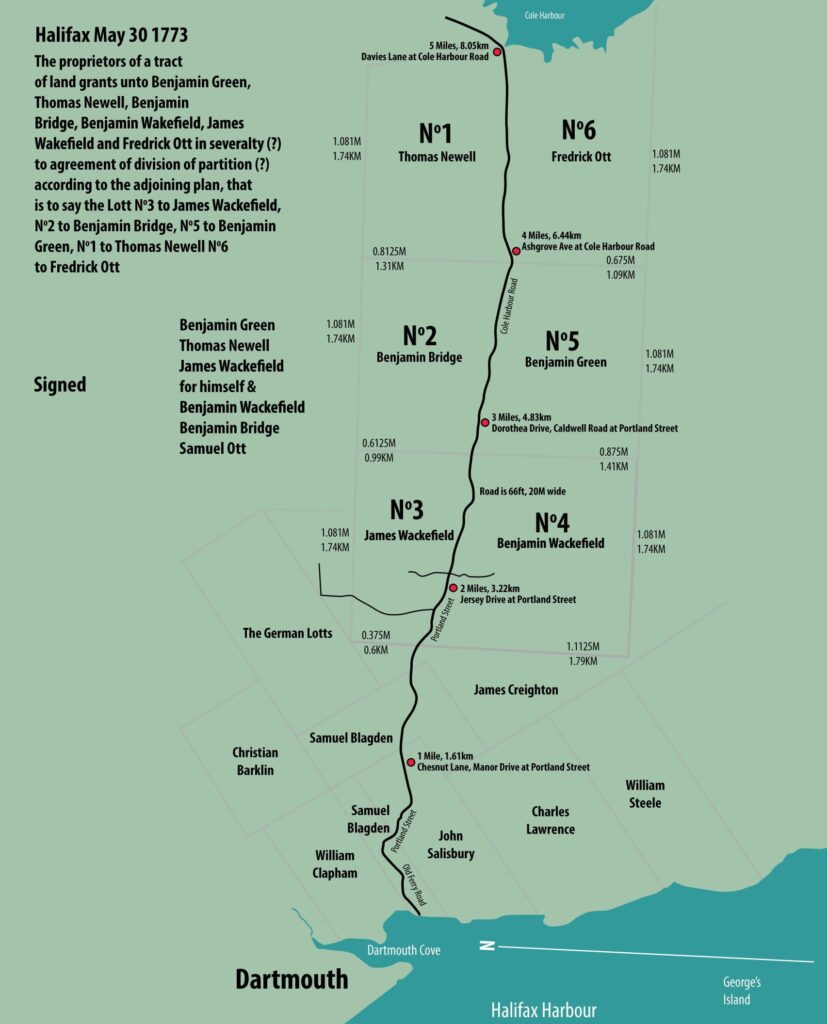

This extensive work was done by German immigrants, who were allotted land outside the pickets. The course of the palisade probably ran from the area close to lot no. 1 of Block “E” which is near the Mayfair Theater and was then a stretch of meadow. It no doubt followed the soft earth around to the northeast corner of Block “I”. Dr. MacMechan’s account says that there was a series of four stockades.

Most likely many inhabitants were scared out of Dartmouth after the massacre, but there is evidence enough in the records to show that the village was not altogether abandoned, as has been repeatedly asserted by various writers.

On St. Paul’s register for May 13th, 14th and 15th, 1751, there is an unusually long list of burials of soldiers and civilians. Among them is the father of John George Pyke who was definitely among the victims of the May massacre at Dartmouth which is thought to have taken place on the night of the 11th.

By 1800 there were many still living who vividly remembered the 1751 massacre. The child described here as having escaped the fury of the [Mi’kmaq] was very likely John George Pyke, who became a member of the House of Assembly and was for many years afterwards a police magistrate of Halifax at the old Court House just up the George Street slope from the ferry landing. His parents had come from England with the first settlers to Dartmouth, and were among the victims of the massacre in 1751. John George Pyke was then about six years of age. Pyke died at Halifax in 1828, where he had been Police Magistrate from the previous century. He was in his 85th year. Mr. Pyke’s figure was a familiar one, clad in drab colored knee breeches with grey yarn stockings and snuff colored coat, sitting in the little police office at the old Court House just up George Street from the Halifax ferry landing.

Many narratives of our early years give one the impression that Dartmouth was a ghost-town from the massacre days until the arrival of the Quakers. But soldiers kept coming and going, and civilians enough remained to create new excitement a few months after the spring [indigenous] raid. In October there occurred a small riot.

The fracas started when Walter Clarke, whose inn stood near the location of the Bowling Academy on Portland Street according to the chart, had an encounter with *John W. Hoffman, a J. P., who had been sent over from Halifax by Commissioner of Peace Ephriam Cook to investigate charges against Clarke; and if necessary take him into custody. So says the Court records.

Clarke was overseer of the German picketers, and perhaps boarded them at his tavern, because the account states that he had them cutting wood and carrying it to the beach on Sundays.

[Clarke] is the man charged with being the chief actor in the Lunenburg riot of 1753 and later imprisoned on George’s Island.

Court records of that time list the complaints of the Germans against the accused of:

1—Struck German people without reason.

2—Obliged the German people to work for him on the Sabbath Day.

3—Employed people to shingle his house on the Sabbath.

4—Employed German carpenters paid by the King, to finish his house, as if the work was done for the King.

5—Sold liquors on the Sabbath.

6—The Constable has found last Sunday his son cutting pickets before his house.

The military ruler of Dartmouth evidently sided with Clarke, for another Court record has a complaint of Mr. Hoffman against Ensign Francis Gilbert of His Excellency Gov. Cornwallis’ Regiment, on October 14, 1751, as follows:

“Hoffman was charged with a letter by Ephriam Cook, Esquire, for Mr. Gilbert—he delivered the letter, then Gilbert called me back saying, Mr. Hoffman, stop, whereupon I stopped, and he asked me what business have you here in Dartmouth. I answered that he had no power to make such a question to me; then he said to me, G- D- you, I will show you another way . . . Then he ordered five soldiers to take me in arrest, carried me as a criminal through *all the town of Dartmouth and I passing in that manner a house, where German people is living in, and Mrs. Clarke, the wife of Walter Clarke standing in the outside of the house, I heard a man’s voice and her loud crying and laughing at me, and I asked her if she did laugh at me, she answered yes, I do, because I see you a prisoner . . . Then I was obliged to go along with the soldiers who kept me in their custody longer than an hour till I was in the boat.”

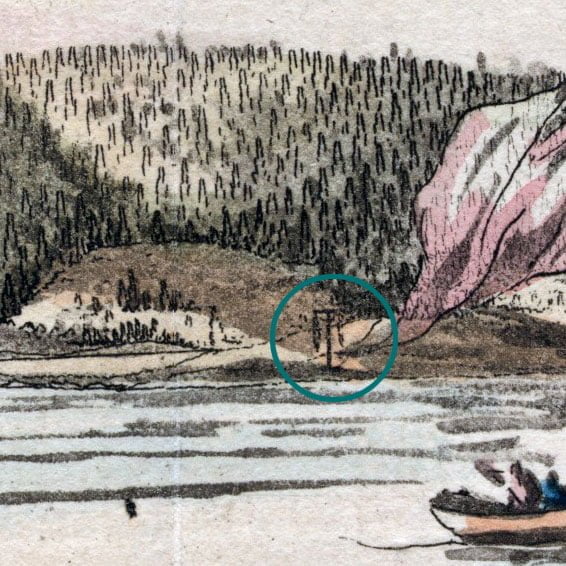

All the rocky elevation of that vicinity extending over to Christ Church cemetery was known as the “North Range”, because it marked the northerly limits of the town plot as originally laid out in 1750. The highest part of this slate rock ridge is in the rear of 98 King Street, just above the Fire Station. On this strategic spot, commanding a view both towards the lakes and the huts below, was projected a military blockhouse for the protection of our first settlers. That height is known as “Blockhouse Hill”.

Around that section known as “North Range” is woven much of Dartmouth’s recorded history. Shipyard Point seems to have been the front part of the original town plot, because Portland Street in the 1700’s was known as Front Street. The back part was the Blockhouse Hill ridge which extends easterly almost to Pine street. As it was from the lake district that [indigenous] attacks were spared, a barricade of spruce trees had been lined up by the inhabitants to fence off their settlement and to entangle the enemy.

Instead of being an obstacle, however, the brush palisade served as cover for the Mi’kmaq warriors when they made a murderous raid on the town in the month of May 1751. This assault inspired Governor Cornwallis to take further precautions, and as a consequence there was an order issued a few weeks later that some newly arrived German settlers were to be landed in Dartmouth, employed “in picketing the back of said Town”.

No doubt part of this picket protection curved down near the back of Christ Church cemetery. This was our first graveyard, for it was used by the families of the Nantucket Whaling Company as back as the 1780’s, and is often referred to as the “old Quaker burying Ground”. Evidently it was then outside the town plot. The lower part of the present cemetery contained a swamp which was covered with water most of the year, according to records from the Quaker days. A large oval-shaped reservoir which used to fill the hollow opposite 40 Park Avenue, probably formed part the pool. The flow of this sluggish water was easterly, and its run can be traced through the cemetery depression and Pine street to the lower part of Myrtle Street, where it curved down Maple Street to Join Saw Mill river running towards Mill Cove.

Thus it is seen that the first town plot of Dartmouth was a peninsula and triangular in shape, with “North Range” as the base line and Shipyard Point as the apex.

Ponds like the Park reservoir teemed with wiggling pollywogs and greenish frogs that croaked all through a midsummer night. Percy F. Ring got a severe bite from a muskrat that he had trapped there 50-odd years ago. Town authorities had a large puncheon sunk into the center of this pool to keep mud out of the hose of the “Lady Dufferin” whenever a fire occurred in that neighborhood.