On January 3rd, 1895, Mayor Sterns and the Councilors attended the state funeral at Halifax of Sir John Thompson, Prime Minister of Canada, who had died at Windsor Castle in December.

In the spring, the “Atlantic Weekly” moved to the southern half of McDonald’s “skyscraper”. The man-power press was usually operated by Tommy Hyles. If he failed to appear for the Saturday morning run, we newsboys used to take turns at the big wheel until enough papers were rolled off to supply our needs. (I walked to South Woodside and back, and averaged 6 cents.)

According to this newspaper, local industries of that time included Starr Manufacturing Co., skates, bolts, nuts and electroplating; employed from 75 to 100 hands depending on orders. The skate business was then on the decline. Dartmouth Ropeworks, when running full time employed 300 hands; Oland’s Brewery 25 men; Torrens’ cornmeal and spice-mill, Windmill Road, six men; Crathorne’s gristmill, (formerly Dooley’s), five men; water-power came down from Albro Lake and entered a mill-race on Jamieson Street near Brodie Street.

Dartmouth Iron Foundry on former Symonds’ place, all styles of stoves, six men. Douglass’ Iron Foundry, Waddell’s wharf, nine men. John Power carriage factory, 85 Portland St., five or six hands. Garrett Kingston carriage factory (Dundas Theatre location) six men. Alexander Hutt carriage factory (Nick’s Restaurant location), eight men. John Ritchie, tinsmith and stove-store, six men employed steadily. N. Russell and Co., established 50 years previously, northwest corner Portland and Dundas, tinsmiths and stove-store, makers of fish and lobster cans; output half a million cans annually, nine men. J. P. Dunn, northern half Simmonds Hardware shop, three men.

Chebucto Marine Railway, slack in winter, but in spring and summer often 100 men employed as shipwrights, caulkers, painters, iron-workers. N. Evans and Sons, boilermakers, 10 or 15 men. John P. Mott and Co., slight falling off that year in shipments to Ontario and Quebec, owing to the depression. Woodside Refinery, output 650 barrels of sugar daily. Ice firms of Glendenning, Carter, Chittick, Hutchinson, Hunt and Otto, employed about 100 men in winter, and half that number in other seasons.

The summer of 1895 is to be particularly noted because in that year was held our first annual celebration— an attraction which has continued with few interruptions down to the present day. Dartmouth had for many years been accustomed to observe the Natal Day of Halifax on June 21st, when schools were closed all day, and most shops shut up at noon. Dominion Day was largely unrecognized, whereas June 21st was a great “out of town” holiday.

“But why not commemorate our own Natal Day” queried townsfolk of that time, “and have such a celebration coincide with the coming of the first train over the new branch railroad?”

As the branch was scheduled to be completed in August, preparations were made early in 1895 to put on some sort of a summer carnival. Railways were to be requested to issue special fares so that train-loads of visitors who had never seen Dartmouth would throng here to note our advantages as an industrial and residential centre, and also to survey the scenery around Dartmouth Lakes, then described as the “Killarney of Nova Scotia”.

By June it was quite evident that the branch would not get finished that year. The Dartmouth Committee, however, went right ahead with their plans for an August regatta and fireworks display at First Lake. All classes of citizens from the well-to-do merchant to the wage-earner were canvassed for cash or other contributions. Among the prizes donated were walking canes, cuff links, spoon oars and hand mirrors. The task of collecting and of arranging a program was largely undertaken by the Chebucto Club members.

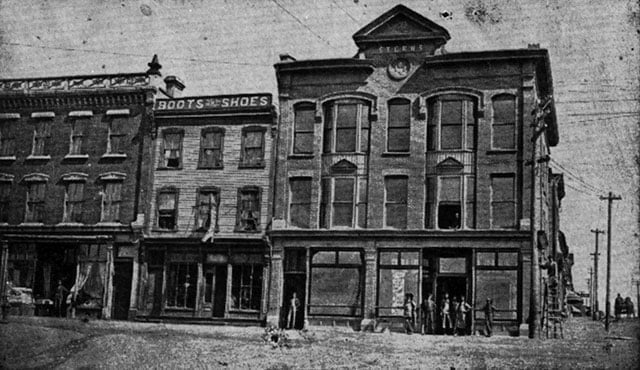

At the request of ratepayers, a public holiday was declared for Wednesday, August 7th. For many, it was only a half-holiday because shop-keepers remained open until the dinner-hour to supply the needs of households. Truckmen like John Jones, Steve Williams and “Tinny” Lee, who often stood for hours by their flat-wagons near Sterns’ store waiting for work, were unusually active hauling sundry equipment and produce towards the tented booths mushrooming up at the lake-side.

Needless to say, the atmosphere that morning was very different from ordinary days. Downtown stores and streets were gaily decorated, as were many private residences all over Dartmouth. On Steamboat Hill, voluminous folds of colored bunting billowed in the light summer breeze. An Italian hurdy-gurdy man from Halifax, with a small monkey attached to a long slender chain, amused an ever-growing crowd of us youngsters at Lawlor’s corner by grinding out bits of Wagnerian opera, while the nimble animal scampered up water-spouts to second-storey windows where he politely doffed his hat on receipt of the proferred penny.

During the afternoon and evening, hackmen reaped a harvest as every trip of the ferryboat landed more and more visitors. All sizes of vehicles, from the single carriage to the four-horse team jammed to the aisles with 10-cent fares, were galloped along the Ochterloney Street level in such a madcap Gilpinian manner that rims of frothy foam fringed the harness of the steaming horses. Never before had so many people been in Dartmouth at the one time. Never might it happen again, speculated the cabbies.

At the lake, a full program of aquatic sports and illuminated boat-parade was carried out very successfully. Two oarsmen, who participated in that first regatta, are still alive at the time of writing. They are John A. Bauld now in his 96th year, who rowed with the four-oared whaler crew of the Mutual Club; and Albert Sawler, 86 years of age, a member of the Turtle Grove crew in the Labrador whaler race. The other men in the Turtle Grove whaler were “Sandy” Patterson, John Lahey and Thomas Lahey.

Members of the Chebucto Club who devoted time, energy and money to institute our annual celebration are here recorded so that their names may be preserved for posterity. They include President Arthur Pyke, W. H. Stevens, Colin McNab, Percy Simmonds, Hope Watt, H. D. Creighton, J. E. Sterns, J. L. Wilson, James Burchell, Dr. F. W. Stevens, W. B. Rankin, Frank Angwin, A. W. F. MacKay, G. A. Sterns, Emery Bishop and o’thers.

In 1895, for the first time in history we got a school holiday on July 1st. The change was brought about as the result of criticism made in the previous year by Councillor A. C. Johnston to the effect that Dartmouth was unpatriotic in keeping school on Dominion Day. For the first time in school history also, the vacation was extended from six to eight weeks. Schools closed that summer on July 5th. The day was Friday and a scorcher.

In that year the Dartmouth Coal and Supply Co., was started by George E. VanBuskirk. Richard Wambolt sold his Halifax-Dartmouth Express business to S. B. Wambolt. Edward Butler now had a boat-hiring service on the present MicMac, Club location. The first electric lights were installed at Christ Church. Sousa’s Band performed at the Exhibition Building, Tower Road, Halifax.

New structures in 1895 were the U.P.C. Hall built by Contractor A. G. Gates; and the residence of the Russell family, which had been gutted by fire in June. E. M. Walker bought the Jenkins property, demolished the old house which had luscious plum-trees in the yard, and erected the building now occupied by Dartmouth Free Press, but then used as a storehouse for provender. A new shop on the west was leased to druggist W. A. Dymond, predecessor of Parker Mott. Contractor J. A. Webber built two houses at the foot of Queen Street, near Pine Street.