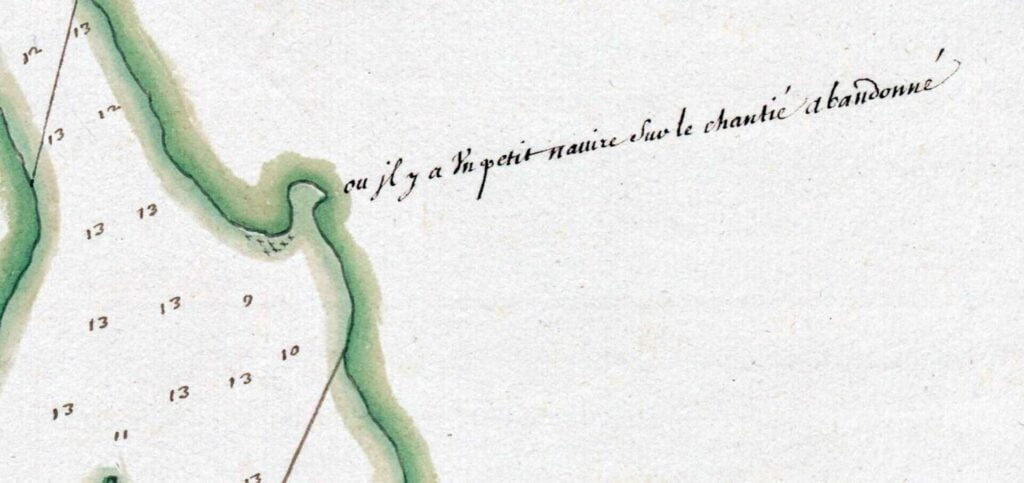

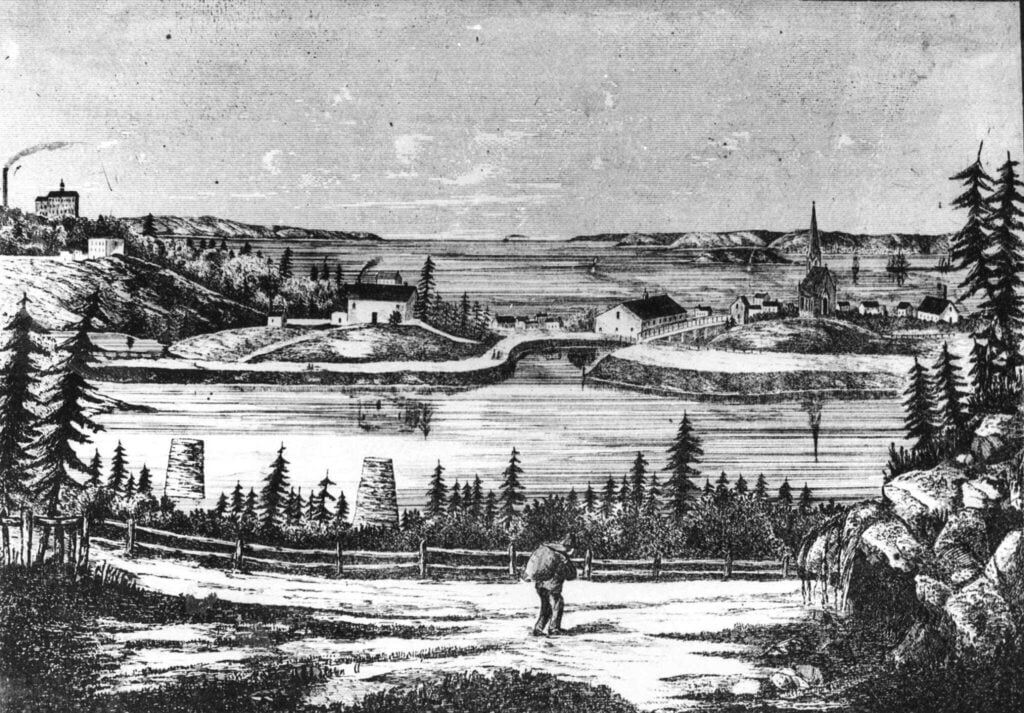

“Where there is a small ship in the abandoned shipyard” seen at Dartmouth Cove.

“Plan de Chibouquetou”, 1600s. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530894278/

Amicitia Crescimus

“Where there is a small ship in the abandoned shipyard” seen at Dartmouth Cove.

“Plan de Chibouquetou”, 1600s. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530894278/

From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

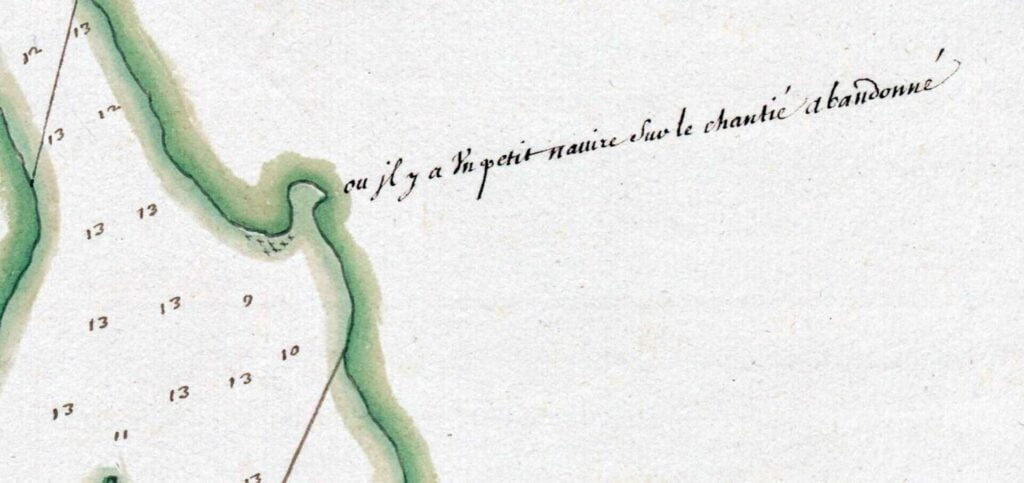

“This first picture was taken at the intersection of Prince Albert Road and Ochterloney Street on Saturday, September 14, 1907 (Below, as it looks in more modern times). The length of the shadow of the telephone pole indicates that the morning is not far advanced, yet there is almost a complete absence of pedestrian or vehicular traffic because by this time of day the market wagons and ice-carts have passed along to the ferry. An occasional delivery team from a downtown store might go by, otherwise, the quietude remained unbroken until noon hour when workmen came out of the Skate Factory for dinner.

The picket fence (hard to see, poor photo quality) at the left enclosed the vacant field of B. H. Eaton (later, Eaton Ave). The fenced-off level due north of the Starr Factory (middle ground) was the route of Bridge Street.

Within the last century, local truckmen and teamsters backed down to the pool at the right to fill water-puncheons or wash their carriages in fine weather.”

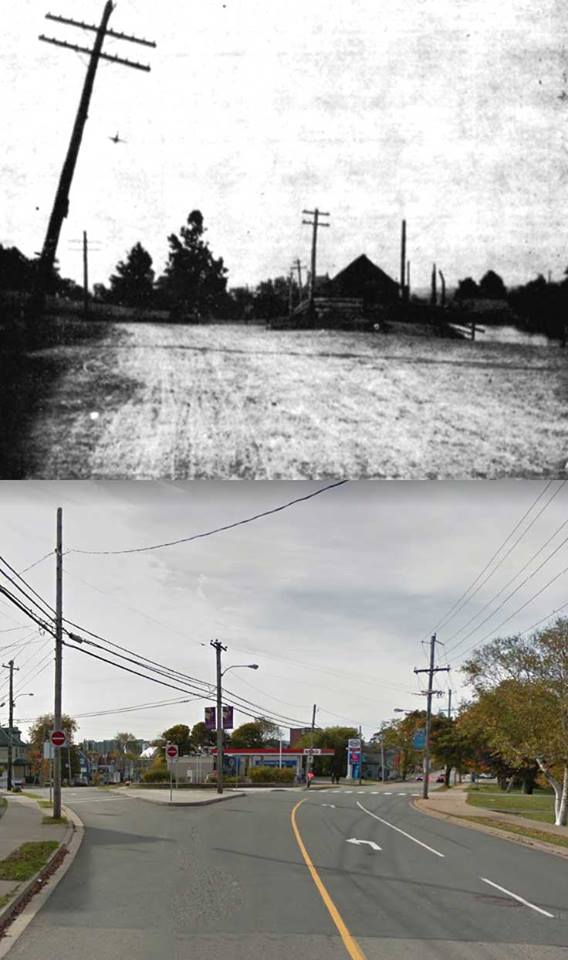

“Traffic to and from downtown Dartmouth crossed a small bridge in the stream opposite the present Memorial Park/ and another bridge at the head of the Starr Works where the road turned northerly to Prince Albert Road. All this was called Bridge Street.

The upper Canal bridge was built in 1886 and Ochterloney Street restored to its present shape. The route used for the previous 25 years over Bridge Street (because of the canal) was then abandoned.”

From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

The removal of the Nantucket Whaling Company to Dartmouth in 1785, gave the town its first major industry; and also brought about a marked change in the shape of the 1750 town-plot. A local commission of inquiry set up in 1783, ruled that all but two of the Dartmouth proprietors had failed to fulfill conditions of their grants. The Legislature of Nova Scotia voted a considerable sum of money to assist this enterprise, because candles, sperm oil and other products were as essential then, as are gasoline and electricity in our own day.

Most of the houses and lots in the town-plot were then escheated by the Government, and re-allotted to the Nantucketers. This procedure caused much discontent and created disputes over titles for years afterwards.

These Quaker people were industrious. Years ago, old residents used to relate how they could erect a dwelling within a few days. They must have been co-operative. No time was spent in excavating cellars. That they intended to remain permanently, is evident from the spaciousness of their houses and from the fact that they constantly cultivated and improved the soil by grubbing-up tons of our familiar slate-rock to build breast-high stonewalls along the borders of their gardens and orchards.

What is perhaps the last of these walls, still supports the bank at the corner of King and Queen Streets. On that elevation, the Quakers erected Dartmouth’s first house of worship. It was in this building that the Dartmouth Society of Friends made their decision to remove to Wales in 1792. Seth Coleman was clerk.

Houses directly opposite the site of the Meeting House at 63, 65, and 67 King Street, with their very small squared panes of glass over the porches, are typical of Nantucket style. And families still prominent on Nantucket Island, whose ancestors migrated to Dartmouth at the time, include names like Coleman, Coffin, Bunker, Greaves, Swaine, Macey, Ray, Barnard, Leppard and Paddock.

Promoters of the Whaling Company, like Hon. Thomas Cochran of Halifax; and leading Quakers like Samuel Starbuck and Timothy Folger (Foal-jer), got whole blocks of downtown property near Dartmouth Cove. Their idea of reserving Dartmouth Common was to provide grazing-ground for owners of livestock in the town-plot. They builded better than they knew, for the Common has always been the town’s chief recreational centre.

Besides their downtown holdings, Messrs. Folger and Starbuck obtained large tracts in the suburbs. One grant in 1787 comprised 1,156 acres in the present Westphal district. Another of 556 acres bordering Edward Foster’s property, seems to be near the Rope-works. These two men also made application for the swamp land of four acres, which was to be drained and improved for English meadow. Historian George Mullane, writing of this period, calls it the “Folger and Starbuck land grab”.

In the same year that the Quakers left, there occurred the death of Christian Bartling. He was of Danish origin. Despite the fact that he had built a house in the 1750’s, yet his property was escheated for the Nantucket families. Later he obtained Crown grants near Lake Banook. The well-known Walker families of Dartmouth are his descendants.

Another name to note is that of Thomas Hardin (no. 5 Block B). As an illustration of tangled titles and also of the hazardous existence of pioneer Dartmouthians, the following quaint petition of Mrs. James Purcell, dated 1792, is most enlightening:

“To the Hon. Richard Bulkeley,

The humble petition of Mary Purcell, the Grand daughter of Thomas Hardin, most humbly sheweth. That your honor will be pleased to remember that my Grand Father was one of the first settlers in Dartmouth and lived on said place until about 15 years ago. And Bequeathed said Lott of Land to my mother Jean Hardin which served her apprenticeship in Your Honors family and my father Lawrence Sliney likewise, at my Marrying my present husband James Purcell, about four years ago My Mother and Uncle Thomas Hardin Resigned over their Right and Title to us for to subsist our Family- Which is a Lott of Land that was granted by Lord Cornwallis to my Grand Father which he suffered a Vast Deal of Hardship in Clearing and Erecting a House on it. Likewise Lost his Son by the [Mi’kmaq] as he was Obliged to Oppose them by Day and by Night. My husband having registered said Lott pursuant to the Laws of the Province.

But now being informed by a Letter from Mr. Morrice Surveyor General that said Lott is made over by a Grant from his Excellency Governor Par and his Majestys Council to one Cristian Barlet in Dartmouth which has had no Right or Title to said Lott but was to pay to our Family Twenty Shillings Currency a Year. Therefore I Beg and Emplore the favour of your Honour to see me and my poor children Rightified. And will be in duly bound to pray”.

In that same summer of 1792, another menace presented itself. All the munitions for the port were then kept at the Eastern Battery. Several thousand barrels of gunpowder stored in a wooden building near the border of the forest caused considerable alarm, there were frequent fires in the woods. In a petition to the House of Assembly, the inhabitants of Halifax expressed fear for the safety of their town, and asked that the munitions be moved in a more suitable storehouse and in a more remote section.

Hartshorne and Tremaine’s gristmill commenced about this time. The firm purchased the lower mill stream and lands on both sides, where Richard Woodin had his dwelling. They also obtained permission from James Creighton, the proprietor of the upper stream, to lower the bank at the outlet of the lake, and to dam up the river in order to provide a head of water for the millrace.

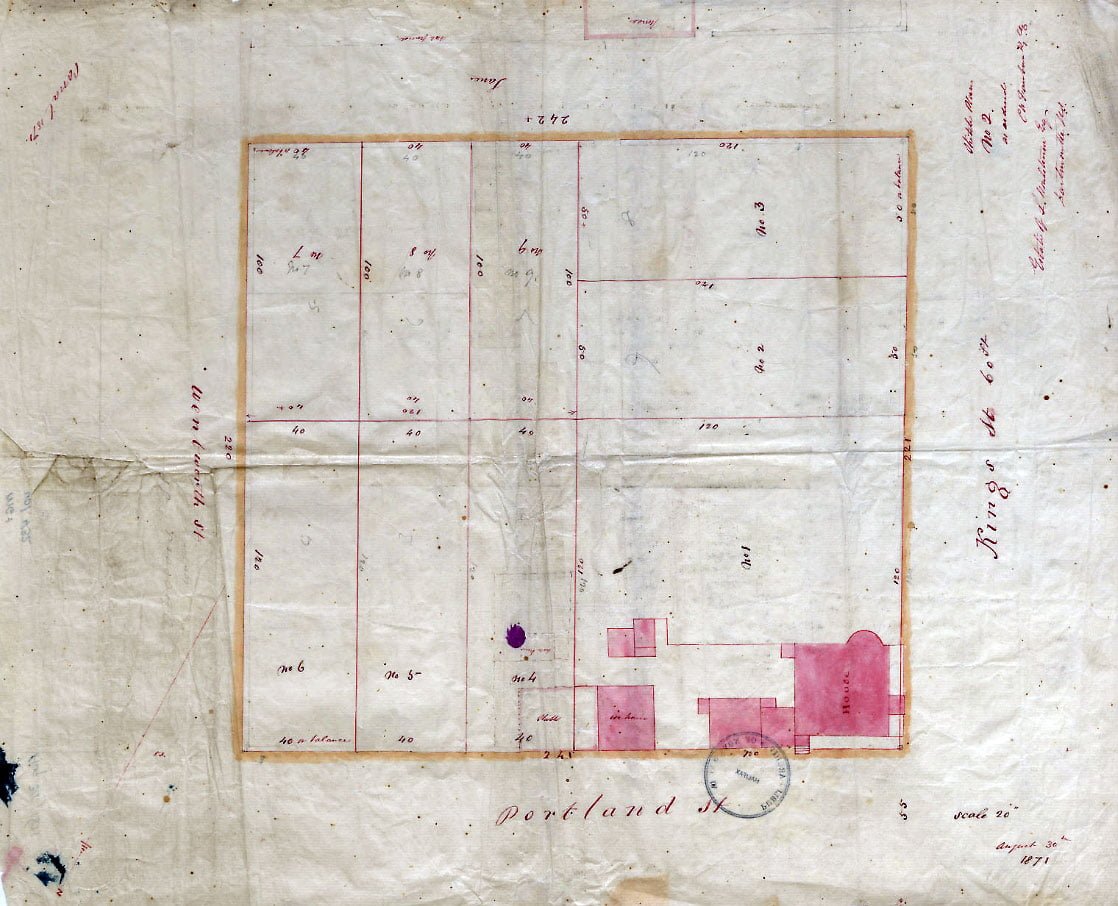

In 1793, Lawrence Hartshorne purchased from Samuel Starbuck, Jr., for £100, the square block “L” bounded by King, Portland, Wentworth and Green Streets. On the old plan it is marked “D”. The lofty tenement building demolished at Woolworth’s corner in 1951, was known a century ago as the “Mansion House” of the Hartshornes. The estate was called “Poplar Hill”.

Jonathan Tremaine acquired the triangular block “M” at Green and King Streets, just below “Poplar Hill”. This had been the property of Samuel Starbuck, senior. But Tremaine’s residence is thought to have been in square block “E”, because he was regranted land at the northeast corner of Portland and Wentworth in 1796, and purchased the remaining lots and buildings in that block from the Starbucks. According to Tremaine genealogy, Jonathan died in 1823 at Dartmouth where he had “a country seat.”

At the same time, the wharves and water-lots left by the Nantucket Whaling Company were also taken over by Hartshorne and Tremaine. For many years this firm had the most extensive flour mill in the Province. Their warehouse was on Water Street in Halifax, whither the finished products were transported by the first vessel built in Dartmouth, “The Maid of the Mill”.

The milling business evidently was profitable in those times, for a third windmill commenced in 1798. An advertisement in the Weekly Chronicle of that year announced that Davis and Barker “have erected a gristmill in Foster’s Cove, and are ready to receive grain to manufacture into flour etc.”

A search through every available record fails to reveal the location of the town-plot ferry-dock during the first four decades of Dartmouth’s history. Certainly the present landing was not the place. The original acclivity of Portland Street can best be gauged by bridging with the eye, the space between the natural heights still seen in the rear of properties on each side of Portland Street, just east of Commercial Street.

The most suitable part of the waterfront for pulling up small boats and erecting cribwork wharves, was on the shelving shore of the crescent-shaped bay which then curved from Queen Street to Church Street. The low-lying land, still seen a few yards west of the Belmont Hotel, indicates that some harbor inlets must have flooded little bays of the original beach now covered with tons of fill leveling the area east of the railway tracks.

During the Quaker period, Zachariah Bunker of the Whaling Company, was located at the southeast corner of Ochterloney and Commercial Streets, where now stands Morris’ Drug Store. On the beach not far from his door he had a water-lot and shed set up, no doubt to ply his trade which was that of a boat-builder.

After the Quakers’ departure, all of Bunker’s town and rural property was bought in 1797 by Dr. John D. Clifford, the ship’s surgeon attached to H.M.S. “Leopard”. Whether Dr. Clifford resided in the corner house is not known, but it was in the above mentioned year that John Skerry commenced his ferry service.

There is no apparent record as to who operated ferries from the 1756 charter of John Rock until Skerry started 40 years later. Perhaps there had not been any organized system, and boats ran privately, for in 1785 a bill was introduced in the Legislature by Hon. Michael Wallace for the establishing of a “public ferry” between Halifax and Dartmouth. This might possibly refer to Creighton’s, or the lower ferry, already mentioned as beginning in the year 1786.

Waterfront plans of those years have Skerry’s dock marked “Maroon Wharf”, which suggests that the foot of Ochterloney Street was the landing-place used by the Jamaica Maroons during the four years that they were billeted at Preston.

Although the story properly belongs to the latter township, yet a brief sketch of the Maroons is included here, because their sojourn in our suburbs stimulated real-estate and transportation activities, and also resulted in the laying-out of a new highway.

The Maroons, deported from the island of Jamaica, arrived in this port in the summer of 1796. For a time they were employed by the Duke of Kent on the Citadel fortifications at Halifax. Later, most of the band were settled at Preston where their superintendents Colonel William D. Quarrell and Alexander Ochterloney bought some 5,000 acres of land with funds furnished by the Government of Jamaica. More was purchased on the Windsor Road near Sackville. In addition, Colonel Quarrell secured several properties in the town-plot of Dartmouth.

From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

In January 1832, there appeared in the “Nova Scotian” seven stanzas of poetry written by “Albyn” at Ellenvale on the occasion of the death of John D. Hawthorn. The latter was a prominent merchant of this community, and a Justice of the Peace. He had been a promoter of the Aboiteau, across the Lawrencetown River near the present railway trestle, which resulted in the reclamation of a wide area of dykeland for hay.

The weather that season continued cold. Ice formed in the Coves and extended all over the harbor by mid-February, when the mercury sank to 12 below. Hundreds amused themselves skating across. Sailing ships could not enter the port owing to heavy drift ice, which for a time clogged the entrance.

As for the unemployed Canal workers, this was the winter of their discontent. Contractor Daniel Hoard had made an assignment and was now incarcerated in the debtors’ jail at Halifax. With the whole project at a standstill, poverty and distress prevailed among helpless families in “Canal Town”, which was only partly relieved by intermittent local charity.

The men appealed successively to Canal officers, to Government officials and finally to Lieutenant-Governor Maitland. Even rioting was threatened.

Some went so far as to set fire to the wooden gates at Lock number 6. This brought forth a proclamation from the Government, offering £50 reward for the culprits.

When the Legislature met that winter, the workmen had a long petition prepared explaining their position. They had not received their hire regularly since the summer of 1831. When later on, several left their jobs, they were persuaded to return by Mr. Dealey, a Company Inspector, who assured them that the pay would soon be forthcoming. They asked that any Government grants for the Canal be applied to their wages.

The petition was signed by:

Robert Hunter, John Turnbull, Robert Wilson, Robert Johnston, Michael Murphy, James Sinnott, Thos. McMillan, John Elliot, Wm. Elliot, James Elliot, Thomas Elliot, Hector Elliot, John Murphy, Nathaniel Russell, Jeremiah Donovan, John Shenston, Paul Shenston, James Colbert, Laurence Feeney, John O’Donnell, Wm. Beattie, Oliver Cumerford, Michael Lahey, Andrew Smith, John Bowes, John Evans, Wm. Carroll, Michael Carroll, David Goggin, John Loney, Pat Galaher, Tim Haley, Wm. Russell, James Russell, jr, John Fisher, Dan Nicholson, Thos. Dey, James Hailey, Luke Langley, Morris Power, Wm. Forren, Tom Sullivan, Morris Conden, Timothy Meagher, Alexander Grant, George Tully, James Fitzgerald, Patt Doyle, Thos. Meagher, Michael Dormady, John Beattie, James Young, James Young, sr, James Shortell, Michael Shortell, Tim Hayley, John Wilson, Patrick Devine, Patrick Shea, James Fenerty, Terry Sullivan, Michael Kennedy, Michael Kennedy 2nd, John Kennedy 2nd, Daniel Keating, Danl Sullivan 2nd, James Walsh, Thomas Shea, John Kennedy 3rd, John Kennedy 4th, Danl Sullivan 1st, Cornelius Kennedy, Thomas Sullivan, Andrew Forhin, Wm. Donohue, Pat Murphy, James Coleman, Thos Hogan, Michael Doweling, John Boyle, John Roatch, Donald Flinn and Walter Currie.

When member John Young read the complaint in the House that February afternoon, Charles R. Fairbanks, representative for Halifax, whose heart and soul was in the Canal project, rose to his feet at once to exculpate the Directors of the Company and lay the blame upon the Contractors.

The latter had been paid in regular installments until, forced by circumstances already described, Company funds had become depleted. This was partly due to the dishonest work of at least one Contractor. The men were in the employ of Contractors, and not of the Company, he said.” Payments to Daniel Hoard had been withheld, pending an adjustment.

Mr. Fairbanks warmly assailed members like John Homer of Barrington, who had called the Canal a “Slough of Despond”, not realizing that £50,000 in British capital was being spent in promoting the development of Nova Scotia. The speaker praised the undertaking as a great public work which would tap our immense natural resources through to Minas Basin, and make Halifax harbor the seaport of the Bay of Fundy.

In March, the House voted a sum of £100 to be used for the relief of the distressed workmen. As a matter of record, Governor Maitland had already paid over that amount.

The petition of the Steam Boat Company that year was not so fortunate. Their application for a grant was opposed by several members who contended that the boat stopped for days, weeks and sometimes months during 1831. Their charter was retained only by running an occasional trip.

Despite the explanations of Messrs. Fairbanks and DeBlois, and their pleas that the Directors were each out of pocket by some £500, the vote was defeated. (This was the first rejection of a ferry grant in ten years.)

Of more local interest was a petition from inhabitants of Cole Harbor, Lawrencetown and Preston Roads. Familiar names like Bissett, Kuhn, Tulloch and Wisdom are appended. Christian Katzman’s name is in large bold handwriting.

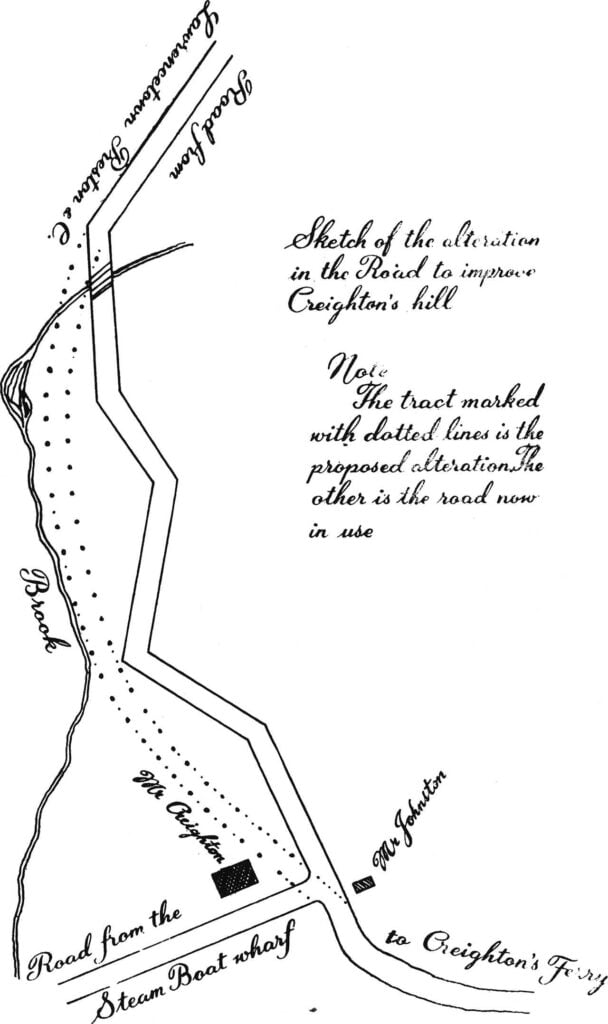

These people asked for assistance to make improvements “on that part of the road leading from the North and South ferries up over Creighton’s Hill”.

As seen above, the road over that immense bank had been originally cut in zigzag fashion in order to lessen the difficulty of climbing up to the level near the present Mount Amelia residence.

This section, known as “Shoulder of Mutton Hill” was noted for its “amazing steepness”, said the petition. Even in the best of weather, “travellers cannot load their waggons with more than one-half the usual load”. The road was cut into, after every rainstorm because the gutter became clogged with mud washing down the sharp slope.

The sentences quoted from the petition, indicate that the Lower Ferry wharf was also the landing place of much heavy merchandise destined for the eastern sections.

We should note here that the petition mentions the use of Old Ferry Road by teams from the “North” ferry, i. e. the Steam Boat terminus. From this fact, we assume that the present Portland Street was not yet cut in a westerly direction from the foot of Maynard Street. The route then from Cole Harbor districts evidently went down Old Ferry Road and turned westerly along Pleasant Street to the Steam Boat wharf.

As a result of the above petition, John Stayner and John Allen of Dartmouth were subsequently instructed to submit plans for altering “Shoulder of Mutton Hill”.

All the real estate of the late Hon. Michael Wallace was auctioned at Dartmouth that year. It included Medley’s Hotel, stable and garden, together with four lots in rear of the house. Also a corner lot opposite the Church, formerly owned by Adam Miller; a lot south of Skerry’s wharf with a water lot in rear; and another water lot at the end of North Street, 100 by 300 feet. Medley bought the Hotel.

The extensive possessions of John D. Hawthorn were also up for sale at auction. His Dartmouth property consisted of two dwellings, coach house, stable, bake house, a store on the wharf and other buildings. At Lawrencetown were his farm lands, horses, cows, sheep, waggons and a large scow.

Thomas Boggs advertised to let the house on Dartmouth Point formerly occupied by him, with coach house, stable, garden and field. Also his wharf in the Cove. Inquiries were to be left with Mr. Hugh Searl, at Dartmouth Hotel.

(From Prince Street to King Street, the railway now runs through the middle section of the original Boggs’ field. It used to be lined with hawsey and chestnut trees. At the intersection of the railway track with the east side of Prince Street, there once stood a fashionable house which was no doubt the Boggs’ residence; although another plan shows a building at the southwest corner of King and South Streets. Boggs’ plank-floored coach house, converted into a dwelling, still stands at the southeast corner of Prince and South Streets.)

Engineer Francis Hall, who was about to leave the Province, advertised his 10-roomed house, garden, stable, outhouses, with a water-lot in front, near the Ferry. Along with it went the whole of his household furniture, “a very superior horse, harness, saddlery, gig and sleigh”.

John Tapper, a blacksmith, who no doubt fashioned ironwork for the Canal, advertised his house for sale. Andrew Malcom, his one-time partner, offered five more in downtown Dartmouth—all heavily mortgaged. The latter’s account books showed long lists of uncollectible bills. Finally he was forced to make an assignment.

James Synott mortgaged to Donald McLennan for £300, three adjoining dwellings northeast corner of South and Water Streets. Also the “land and store on the north side of the old road leading from Dartmouth to Preston, said road now being obstructed and shut up by the waste-weir”. (Lower stretch of Crichton Avenue on east side.)

John Skerry purchased for £85, two seven-acre lots of Abbeville estate with buildings thereon, commencing at the northeast corner of School Street and Victoria Road. (Until new streets were laid out in that vicinity, the surrounding pastures and woods continued to be called Skerry’s fields.)

Alexander Lyle sold for £40 to Thomas Marvin, block-maker, the property which is now no. 6 Commercial Street.

A lot of land 50 yards from the northeast corner of Ochterloney and Dundas Streets “on which corner stands John Chamberlain’s dwelling”, in Block “A” which had been granted to Christ Church along with Block “G”, was sold in 1832 for £25 to Robert McNesly. The proceeds were used to discharge debts due on the new Parsonage.

James Stanford, the tanner, bought for £85 two of the lots on Ochterloney Street. It comprised a large area of lowland and stream near the present Maple Street.

The first record of the ferry being used for a fire-boat was logged in October of 1832, when the “Sir Charles Ogle” interrupted her schedule to transport the Dartmouth Firemen to fight a conflagration which was raging in the vicinity of Cunard’s buildings at the foot of Proctor Street in Halifax. The newspapers reported that the fire engine “worked on board the Steam Boat, assisted very materially in checking the spread of flames in the rear of the buildings”.

There was a very fashionable wedding out at Mount Edward that summer when widower S. G. W. Archibald, then Attorney General for Nova Scotia, was married to Mrs. Brinley, widow of William Birch Brinley. Rev. Mr. DesBrisay officiated. The same Minister performed the marriage at Dartmouth of Martha Vaughan to Francis Hoard.

Among Dartmouth baptisms were Henry, child of Sophia and Joseph Frame, farmer; Margaret and John, twin children of Maria and John Morton, laborer.

John Thomas Wilson, aged 11, (also on school register) was drowned while skating on the Canal just before Christmas.

A similar tragedy was reported the previous March, when Robert Mills, who missed the last boat at night, attempted to cross to Halifax on the ice opposite the Naval Yard, and was never seen afterwards. He left a widow and two sons.

Other deaths recorded were Michael Meagher, of Dartmouth, aged 39; and Francis Mizangeau aged 30 at Eastern Passage.

Notable deaths abroad in 1832 included Sir Walter Scott. When news reached here in November, it brought forth from “Albyn”, an elegy filling nearly three newspaper columns.

From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

By 1842, when Dartmouth was nearly 100 years old, there still seemed to be no regular system of mail transportation. About that time, a resident complained to the newspapers that letters from abroad, addressed to Dartmouth, were detained at Halifax until nearly half a bushel had accumulated. Then they were sent over by a carrier who charged one penny on each letter for his trouble.

There was no recognized Post Office in Dartmouth until about 1870. Instead there was a “way office”. In small centers, such as ours, letters were left at the village store, commonly known as two-penny offices, because the keepers charged two pence on every letter passing through their hands. A letter from England to Halifax would cost 20 cents, but it might be taxed 16 or 18 cents extra to send it a few miles farther—all depending on the number of way-offices through which the letter would pass. As a consequence, there were more letters in the pockets of passengers on stage-coaches, than there were in the mail bags.

The Dartmouth way-office about this time, is thought to have been at McDonald’s general store. Dr. John McDonald, who is now managing the business since the death of his half-brother Allan, must have been a man of some ability, as he was appointed one of the Governors of Dalhousie College in 1842, and also made a Justice of the Peace for Dartmouth.

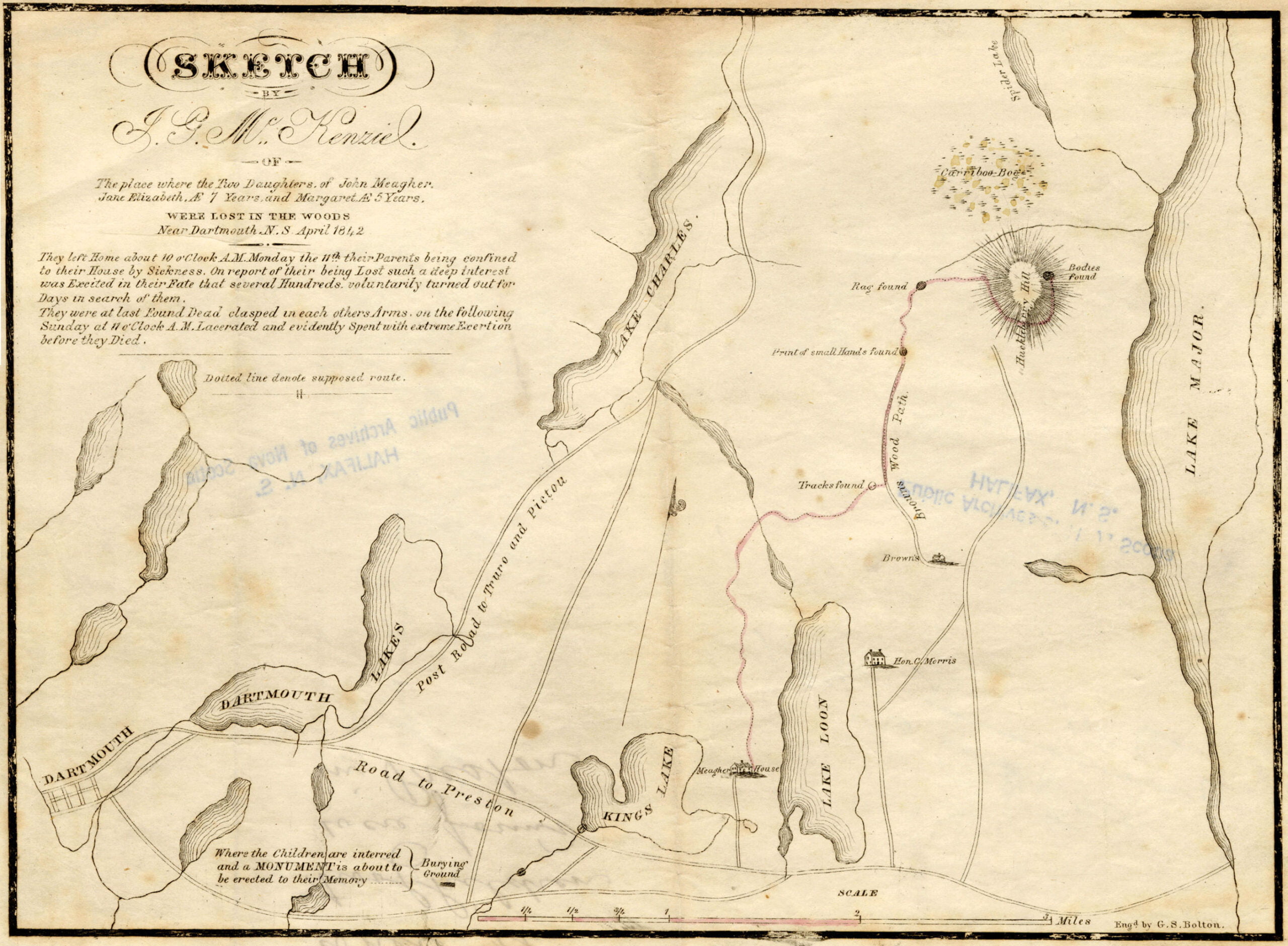

In mid-April 1842, the greatest excitement was aroused in Dartmouth and Halifax by the loss of two little girls, who were the daughters of Mr. and Mrs. John Meagher, occupants of a farm at Lake Loon at the northern extremity of Barker Road on no. 7 highway.

These children were Jane Elizabeth and Margaret Meagher, aged 6 years and 4 years, respectively. They wandered into the woods near their home on a beautifully warm Monday morning, the 11th day of April. The eldest sister of the family was busy with household duties, while the mother with a new-born babe was still confined to her room. Unfortunately also, the father was laid up at the time with an attack of measles.

When the little ones did not return by late afternoon, the hired man searched far into the woods at the rear of the field, but returned unsuccessful. Then the father rose from his sick bed, and with the help of neighbors carrying lighted brands, tramped deeper and deeper into the pathless forest loudly calling the names of Jane and Margaret, but all they got for their efforts was a rebound of the eerie echoes of their voices from the distant tree-tops.

When news reached town on Tuesday, hundreds of volunteers hastened from Halifax and Dartmouth to assist in the hunt. Hope was aroused when the searchers saw footprints in the snow, and also learned from a young Black man named Brown, who lived about two miles from Meagher’s on the opposite side of Lake Loon, that he had heard voices of children crying on the previous evening.

During the whole of that week, an ever-increasing crowd of volunteers comprising neighbors, farmers, Frenchmen, Mi’kmaq, sailors, soldiers, merchants and professional men, threaded nearly every foot of that vast forest until it seemed as if the whole countryside had been combed. Meantime, the weather had grown so cold that it was the general conviction the children must have perished.

Halifax newspapers, nevertheless, issued an appeal for every available man to assemble at Dartmouth on Sunday, April 17, for a combined and organized effort. Nearly three thousand responded. They were determined that the forest should reveal its secret. And it did.

About noon that day the bodies were found on a hill at the head of Lake Major, almost two miles east of the village of Montague. The hero of the hunt was a shepherd dog named “Rover”, scouting in the company of Peter Currie, a neighbor of John Meagher. “Rover” had suddenly sniffed the trail of the babes, and with his nose in the scraggy turf, scurried up a hill to the sheltered side of a high boulder. There he stopped and barked excitedly.

The children were found locked in each other’s arms. The younger one had her cheek tightly pressed against the face of her sister. Young Margaret’s features were calm and peaceful as if she had met death in sleep. Elizabeth’s face, however, plainly showed traces of fear and anxiety, and spoke of days of cold, of hunger and terror. Their tender arms and legs were covered with scratches, and their flimsy dresses in tatters. They had traveled about six miles.

The bodies were left undisturbed until the father was escorted to the spot. Many in that motley throng, now gathering around reverentially amid the awful presence of death, could not restrain a tear as the stricken parent knelt and lovingly embraced each lifeless form. Willing hands, working in relays, then carefully carried the precious burdens back to the Meagher home.

The remains were placed into one coffin, and two days later were interred in the historic cemetery at Woodlawn. A reward of £5 offered for their discovery, was turned over by Mr. Currie to head a fund for the erection of a headstone.

From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

At Silver’s Hill, the slope no doubt originally extended down to the lake shore. Pioneer trails generally avoided lowlands. Hence this “new” road to Preston followed the broad path still seen on the hillside below Sinclair Street, until it emerged around the bend at that bay of the lake called by the Mi’kmaq “Hooganinny Cove”.

The causeway-bridge over Carter’s Pond at the town limits, was very likely built during the time of the Maroons, for the road is shown on military maps as early as 1808, indicating that this section of highway had been constructed some years previously.

In the year 1808 Mrs. Jonathan (Almy) Elliot, widow, was married to Nathaniel Russell, widower, of Russell’s Lake, who had been long bereft of all his family. Of the Russell union, one son Nathaniel was thus a half-brother to the Elliot children.

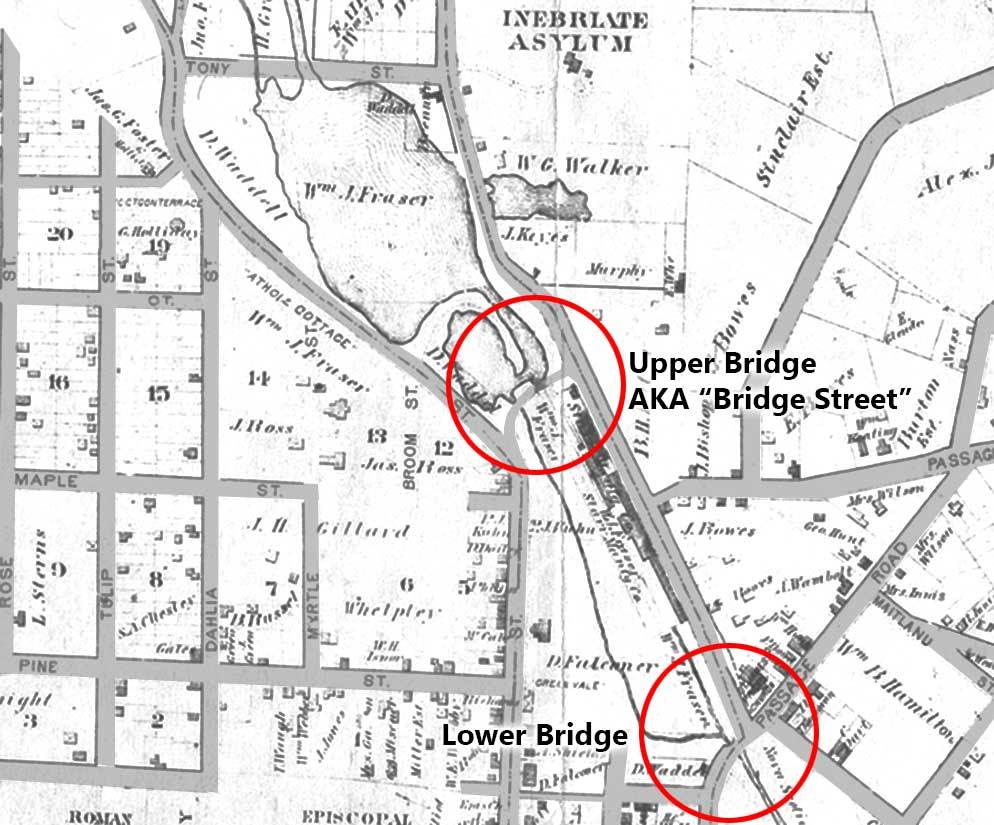

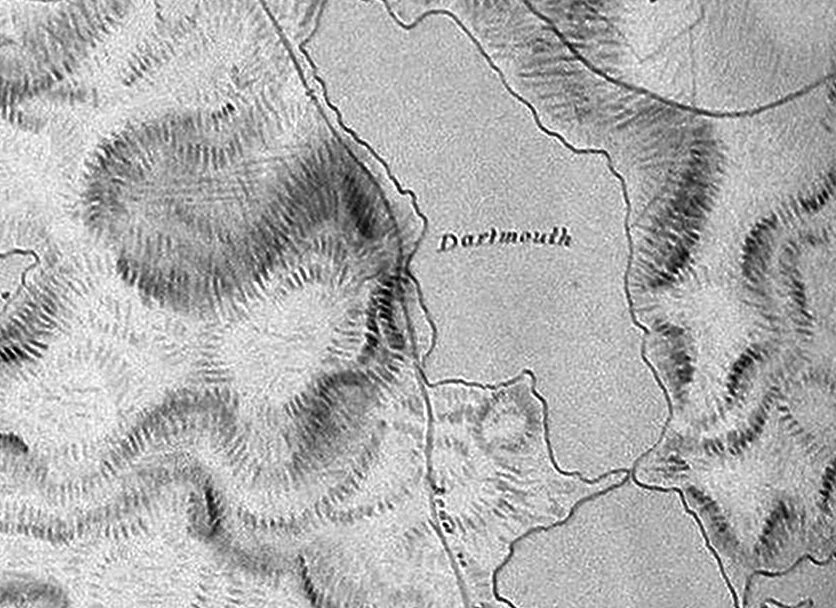

“Hooganinny Cove”, around the bend near the notation of “Dartmouth” on First Lake, as seen in 1808.