“Prior attempts to settle Dartmouth had not thrived. In August, 1750, the ship Alderney had arrived from England with over 300 settlers and house-lots were assigned to them in a planned new town. Unfortunately, the town had been laid out on the traditional summer camping ground of the native Mi’kmaqs. In May, 1751, the Mi’kmaqs attacked the settlement, killing at least four and taking others prisoner. Most of the English settlers were frightened away. Although from five to several dozen families resided in Dartmouth in the years following 1751, settlement remained sparse. In 1783, when Loyalists arrived from New York, many Loyalists camped in Dartmouth while waiting for settlement of their claims for losses during the American Revolution. But most moved on to grants of large acreages throughout Nova Scotia. Parr and the Provincial Council were interested in attracting settlers and in developing new industry. Governor Parr knew the whaling industry would be an economic boon to the development of Dartmouth. He welcomed the Quakers who were not only skilled mariners but were known as hardworking and of good conduct.

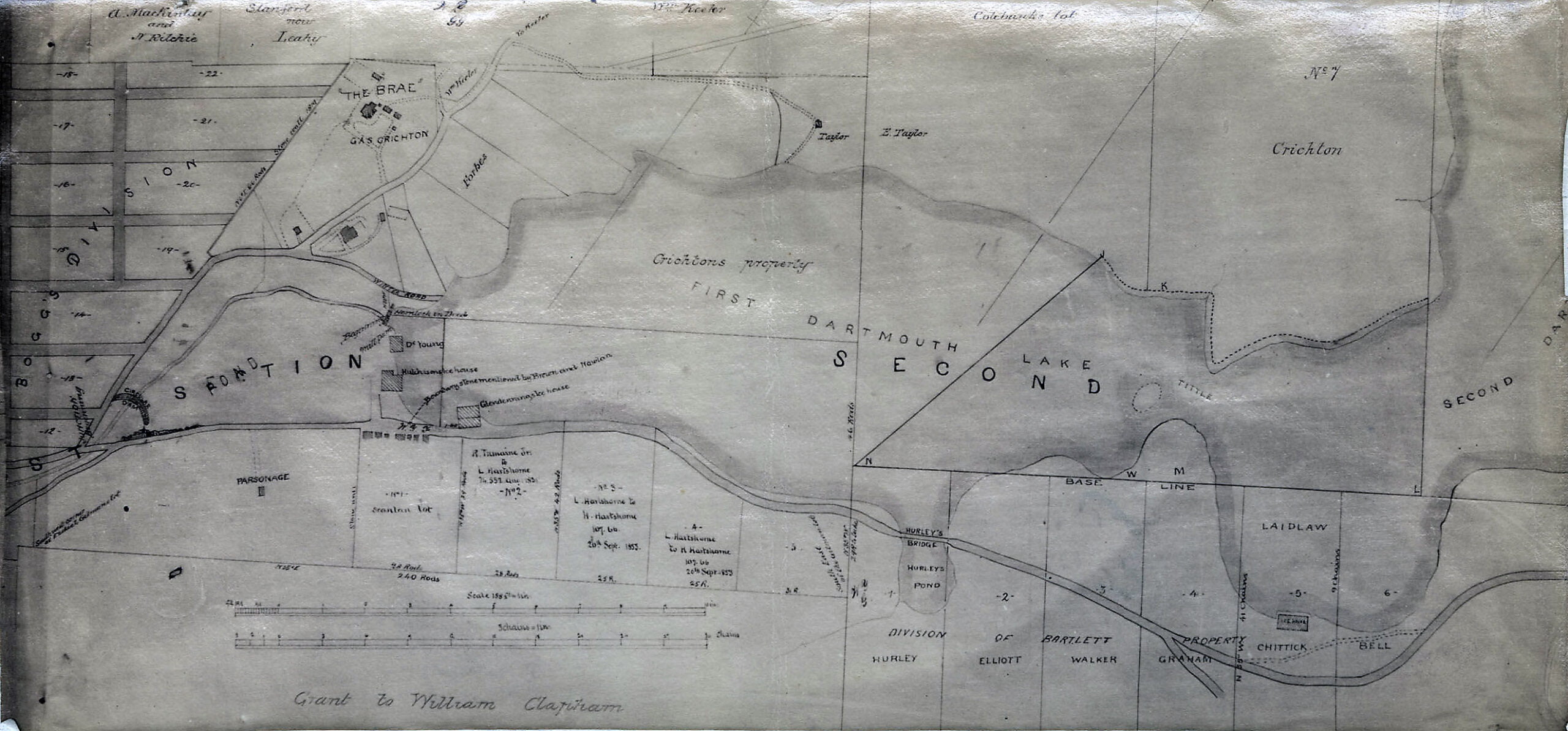

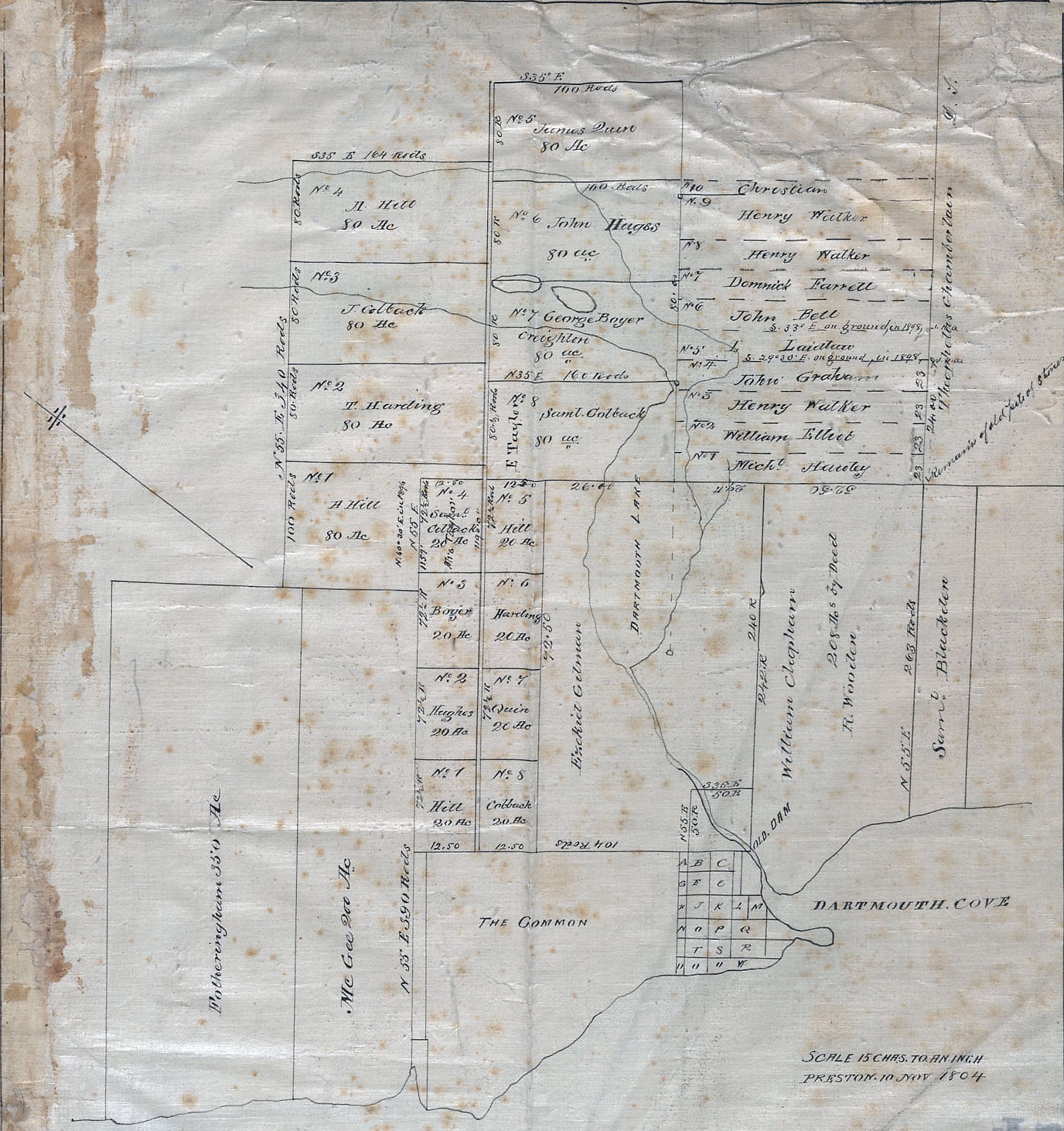

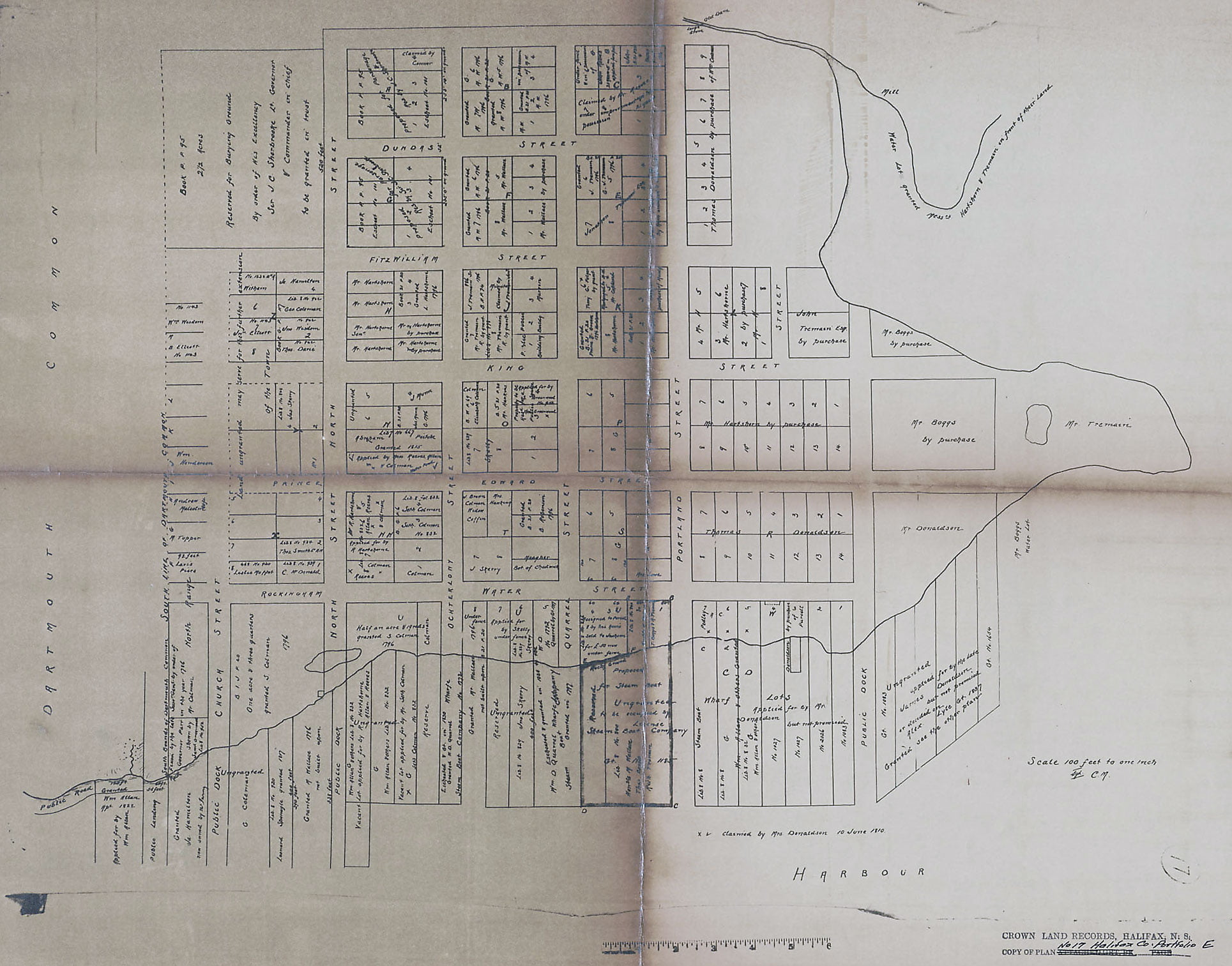

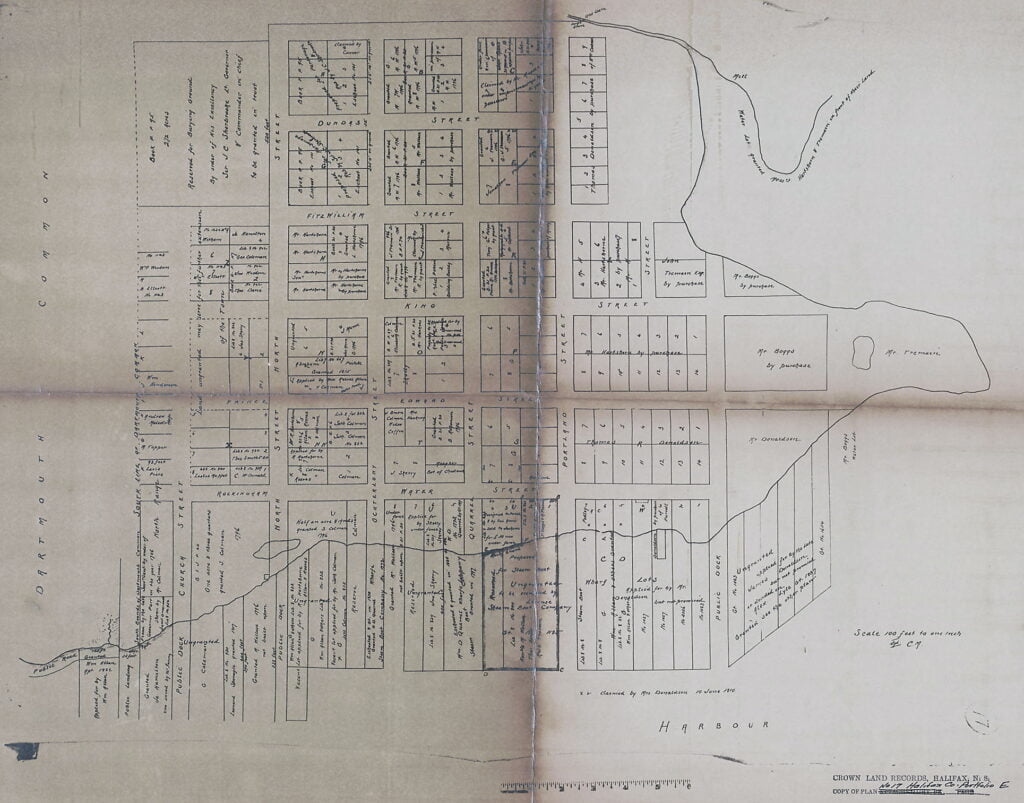

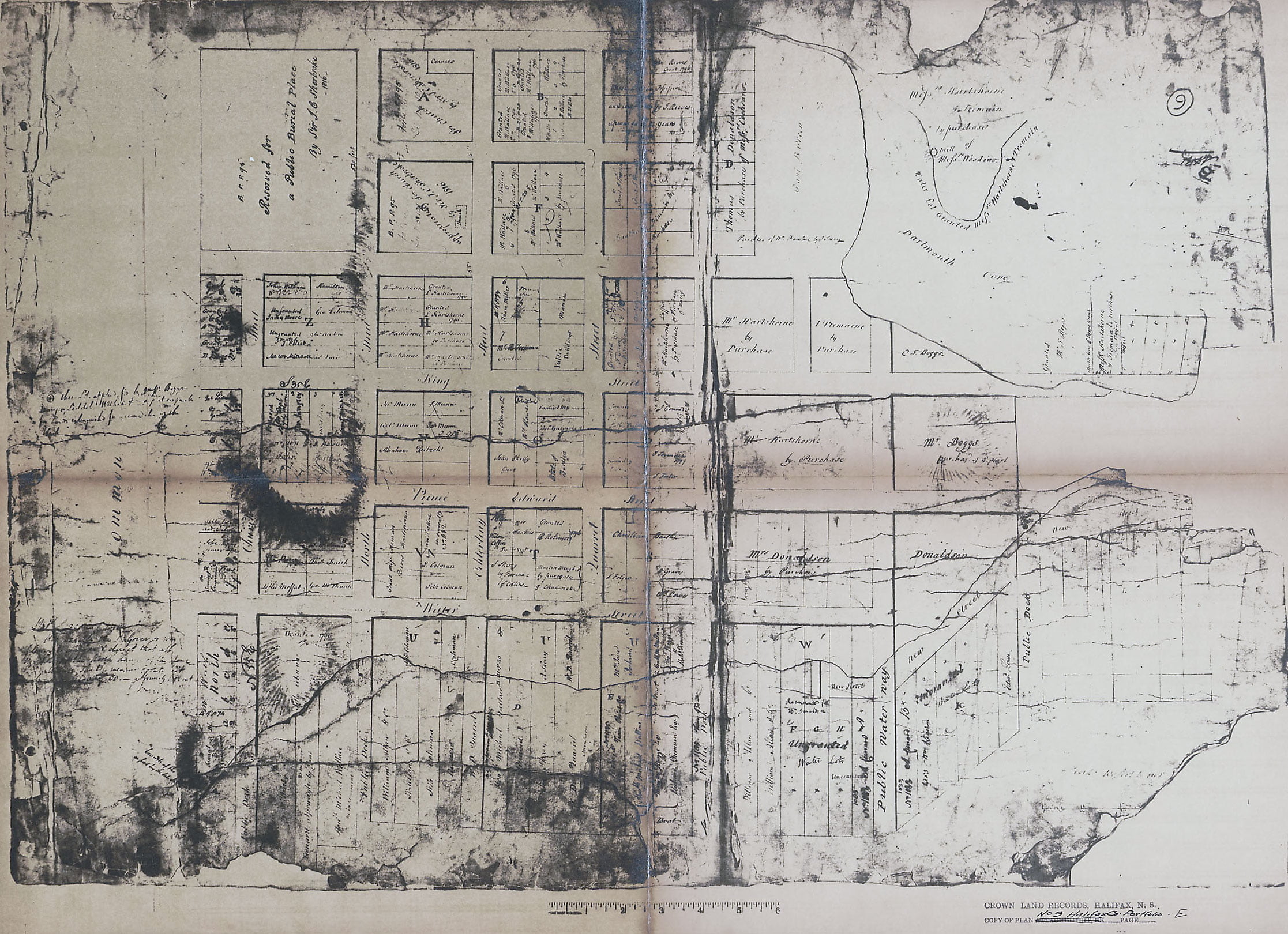

In settling the Quaker Whalers, Governor Parr ordered the Chief Land Surveyor to re- survey the town plots in Dartmouth and as- sign them to the Quaker families. The Com-mission appointed by Parr planned to build 22 houses but some house-frames were “blown down by an uncommon Gale of Wind and much broken and damaged,” so only 12 two-family houses were completed. Soon, the new settlers were moving in the furniture they had brought with them, putting in gardens and digging wells. The township was laid out with streets in a grid pattern with an average of eight lots making up each block. Samuel Starbuck, his wife Abigail, their son Samuel, Jr., his wife Lucretia and their two young children were assigned lots on the block on the corner of the present Wentworth & Portland Streets in Dartmouth. The Folgers received three plots, one for the parents, Timothy, Sr. and Abial; and one each for the two sons’ families: Timothy Jr. and his wife Sarah; and Benjamin Franklin Folger and his wife Mary. Timothy and Abial’s daughter Peggy Folger and her husband David Grieve also were provided a plot, as was their daughter Sarah and her husband Peter Macy. Names of other Nantucket families who were assigned lots were: Barnard, Bunker, Chadwick, Coffin, Coleman, Foster, Macy, Paddock, Ray, Robinson, Slade and Swain. These early simple frame houses stood for many years until over time, one after another, they were pulled down to make way for larger, more modern buildings. The only one of the Quaker settlement houses remaining today is that of William Ray at 57/59 Ochterloney Street, built in 1786 and now the oldest house in Dartmouth. Concerned about saving this heritage building, citizens of the Dart- mouth Museum Society bought the house in 1971 and it is now preserved as “Quaker House,” part of the Dartmouth Heritage Museum.

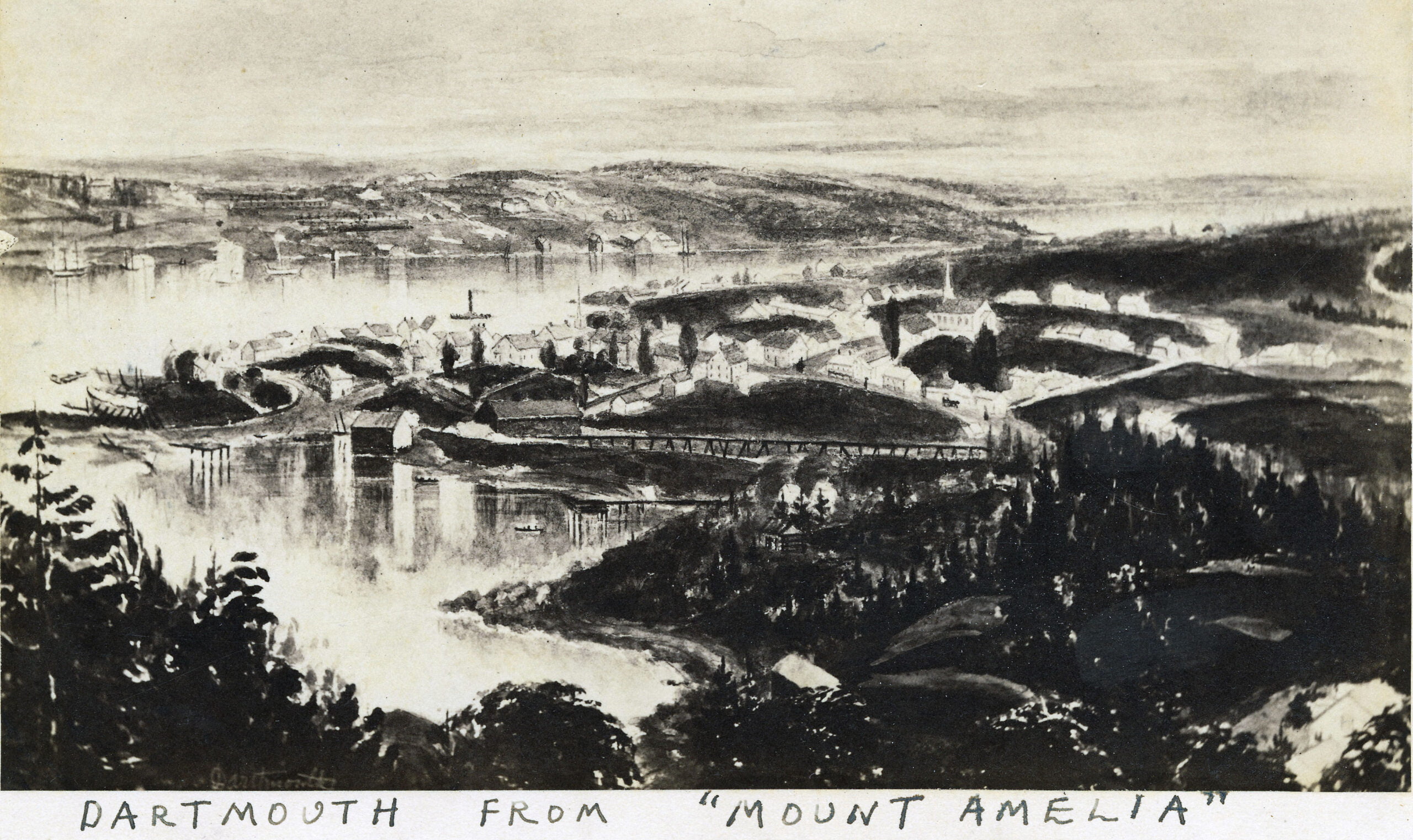

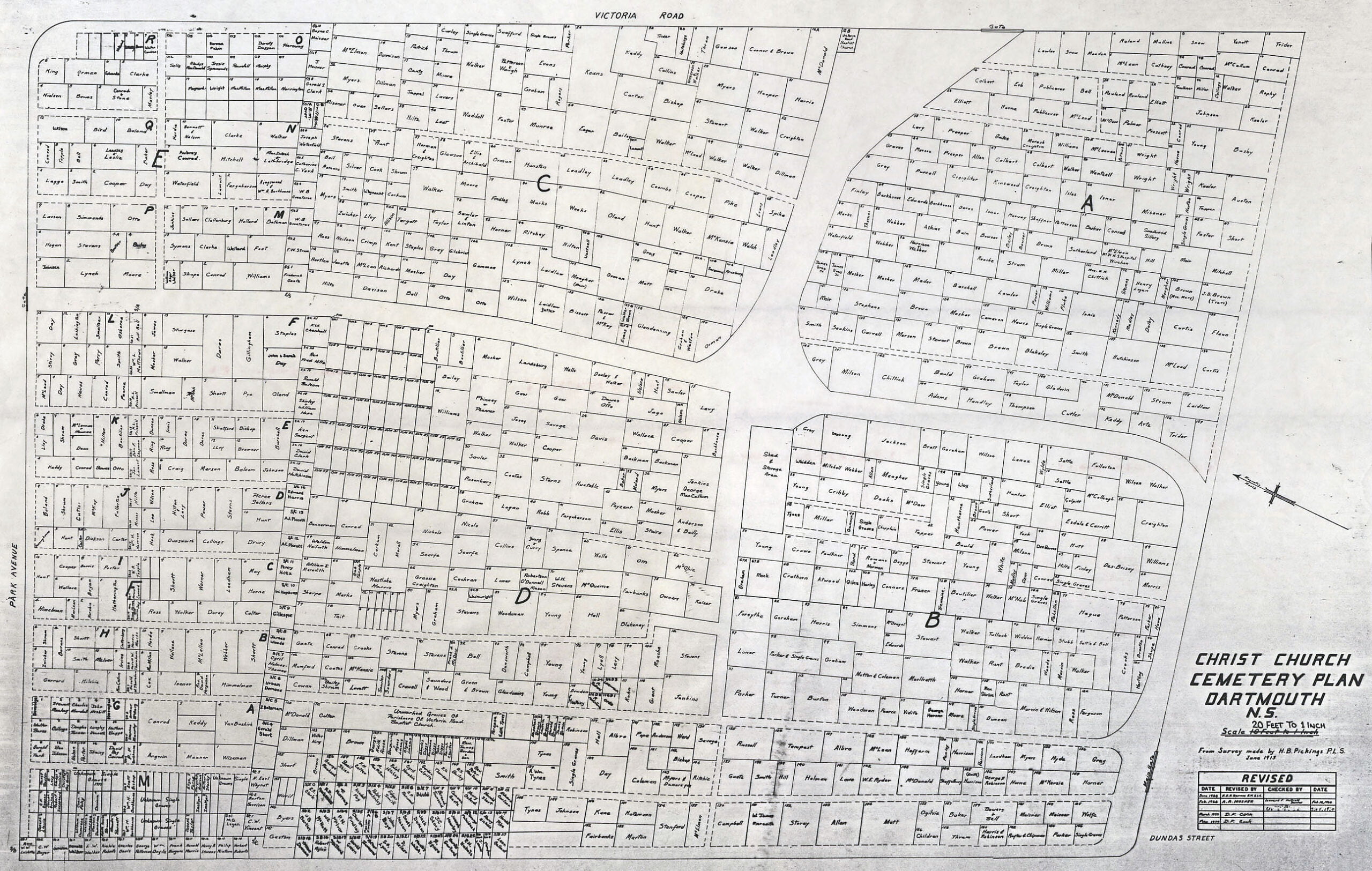

Not only were houses built but docks and warehouses, essential for sending out ships and handling cargo, were erected on the shores of Mill Cove in Dartmouth. “Within one season the land was converted into a thriving sea port.” A plot was set aside for a Friends Meeting House, which was soon built, the exact date uncertain. The site of the Meeting House was where the present Post Office Building stands. (This Meeting House is mentioned by traveling minister Joseph Hoag in September, 1801: …”We appointed a meeting in the evening at Friends meeting house in Dartmouth.”). During 1786, the Friends held Meetings on First Day (Sunday) and in October, 1786, sent a letter to Nantucket Monthly Meeting requesting that the Dartmouth Friends be recognized as an established Meeting of the Society of Friends. The Dartmouth Meeting was advised to continue holding Meetings for Worship and eventually, after the request was referred to Sandwich Quarterly Meeting and New England Yearly Meeting, Dartmouth was recognized as a Preparative Meeting under the care of Nantucket Monthly Meeting. The Friends also established a burial ground on a hill overlooking the town. There Friends who passed away were laid but without markers in a place carpeted by grass and shaded by ancient trees, as these early Friends considered monuments to be too worldly. The site of the Quaker burial ground is now part of the Anglican Cemetery.”

“The British Government Discourages Development in Nova Scotia

Governor Parr’s efforts to enable the Province of Nova Scotia to be self-sustaining were not appreciated by the British government in London. The well-being of its colonies was not of interest to the British who considered colonies to exist primarily for the benefit of the mother country. Under the policy of mercantilism, colonies were seen as providing cheap raw materials to the home country while being consumers for the home country’s manufactured products. Successful colonial manufacturies were rivals to be discouraged. The British government decided that whaling vessels as well as the whale- related industries of refining oil, making candles and the subsidiary work of boat-building, sail-making and ship chandleries, should be based in the home nation to provide work and profit for Britains. They had missed the opportunity presented by William Rotch in 1785 of allowing a colony of Nantucket whalers to set up their base in England. The British acted to encourage whalers to emigrate to the home island after finding Rotch’s whalers established on the soil of Britain’s great enemy, France, the next year. The Nova Scotian governor was instructed to discourage the whal- ing colony in Dartmouth in order to bring the Nantucket whalers to Britain. “It is the present Determination of Government,” wrote the British Home Secretary, “not to encourage the Southern Whale Fishery that may be carried on by Persons who may have removed from Nantucket and other places within the American States excepting they shall exercise the Fishery directly from Great Britain.”

Follini, Maida Barton. “A QUAKER ODYSSEY: The Migration of Quaker Whalers from Nantucket, Massachusetts to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia and Milford Haven, Wales.” Canadian Quaker History Journal, vol. 71, 2006. https://documents.pub/document/a-quaker-odyssey-the-migration-of-quaker-whalers-from-cfhainfo-shire-wales.html?page=21