“To the cast, Nova Scotia; seemed to offer promise to the Revolutionaries. Three-quarters of its population had come from New England and showed a lively sympathy for the rebellion. Geography and the British navy, however, overruled sentiment and kept Nova Scotia; in the Empire. The distances and the wilderness which intervened between the scattered settlements. of the colony made it impossible for American sympathizers there to organize an effective force and to attain the unity of plan and of action necessary to military success. Washington refused to send an army north to capture “New England’s outpost”. He knew that an invasion must go by sea and that the British fleet could intercept supplies and reinforcements sent from the south. The invaders, cut off from succor or retreat and trapped between the Royal Navy and the wilderness and bogs of the interior , would fall an easy prey to the redcoats.

At the peace negotiations the wily Ben Franklin tried to gain by diplomacy what American arms had failed to take. He urged the British to cede Quebec to allay the rancors of war and to avoid future friction. This bold proposal did not convince the British, and Canada remained in the Empire. It is significant to note that the American plenipotentiaries showed little interest in the acquisition of Nova Scotia. Geography made Quebec a potential threat to the new nation, but Nova Scotia; gave them little concern.”

“The development of a “commerce of convenience” helped to increase Canadian-American trade. For example, Canada West purchased its coal from nearby Pennsylvania, while New England bought its fuel from Nova Scotia;. This type of trade was developing prior to 1854; the (Reciporocity Treaty of 1854) stimulated it, but did not cause it.”

“At the beginning of the Civil War, the assembly of Nova Scotia; asked the home government to state its attitude toward the union of British North America. The colonial secretary replied that the cabinet would give serious consideration to any such proposal from the colonies. The governments of the other provinces, however, considered the suggestion premature.44 But growing fear of American military force or economic pressure rapidly ripened their desire for closer unity. In the waning summer of 1864, the governments of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island called a conference at Charlottetown to consider the formation of a Maritime federation. A delegation from Canada appeared before this meeting and convinced it that the wider latitude of a union of all British North American colonies was possible and necessary.”

“Hostilities in the Maritimes, however, doomed the drive for a speedy confederation. Their people had initiated the movement for union and expected that leadership would be the reward of authorship. Instead, it was painfully apparent that Canada would assume the dominant position in the federation and the Maritimes would be a minority with particular interests which might be subverted by the majority.48 A psychological factor complicated the situation: particularism was a salient characteristic of political thinking in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. The people of these colonies lived in their own world, geographically separated from the St. Lawrence Valley and with little desire to be politically coupled to it; they lived by and from the sea and tended to look out upon it and not toward the heart of the continent.”

“The Maritimes had been wedded to free trade, for they depended upon lumbering and fishing for their livelihood and had to import much of what they consumed. Canada, on the other hand, dreamed of industrialization and would surely girdle the new union with its tariff wall.49 Nova Scotia particularly disliked the financial terms which would compel her to surrender most of her sources of revenue to the central government, receiving in return an annual per capita subvention of eighty cents. Such a bargain would beggar them. The income of the provincial government which had been $1,500,000 in 1865 would shrink to $750,000 under confederation. Besides, the province would have to contribute $640,000 annually to the upkeep of the new government, leaving little to support such necessities as education and public works.50

These were the reasons sufficient to impel the people of the Maritimes to resist adoption of the Quebec resolutions. The governments of Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island rejected the scheme out of hand, but they were small and peripheral colonies whose adherence was not considered essential. It was quite otherwise with Nova Scotia; and New Brunswick; the completion of the union depended upon their acceptance. When S. L. Tilley, the confederationist premier of New Brunswick dissolved his assembly and held an election on the question of confederation, he was roundly beaten.52 Dr. Charles Tupper, leader of the Nova;Scotian government and likewise a confederationist, learned wisdom from this example and did not make an issue of union in his colony. But the damage was done.”

“New Brunswick was the geographic pivot of the proposed federation, and its rejection of the scheme seemed a fatal wound. Fortunately, this was the darkness before dawn, and other forces were soon at work moving the recalcitrant province. The British government put its overwhelming pressure upon New Brunswick to accept the Quebec Resolutions. Lieutenant Governor Sir Arthur H. Gordon, who had sympathized with the anti-confederationists, was a hasty convert to the “true faith” upon receipt of a sharp admonition from the colonial secretary.53

The voting public lacked such clarifying revelations, but found the same conclusion in other experiences. They were deeply disappointed by the failure of attempts to renew reciprocity, upon which they had counted heavily. Talk of annexation in the United States, in Canada, and in New Brunswick itself gave them concern, and the Fenian raids frightened them.54 The chastened Gordon virtually forced a new election on his anti-confederationist government in 1866, and the results of the previous year were reversed. Nova Scotia also found the ways of righteousness, though through an iniquitous bypath. The wily Tupper, who had declined to challenge the federation question by making it an election issue, coaxed from his assembly a

resolution providing for the renewal of negotiations for union. Using this as a virtual carte blanche, he dispatched a delegation to London, where they joined representatives of the other two colonies. The upshot was the enactment of confederation by the British Parliament in the form of the British North America Act.

The anticonfederationists fumed and sputtered at this trick which Tupper had played upon them, and none more than their leader, Joseph Howe, a great and yet a pathetic figure in the history of British North America. He had had his day of glory when he led, and won, the struggle for responsible government in his colony. His interminable journeyings and campaigns throughout Nova Scotia had added to the fame which this victory had given him. There was scarcely an inhabitant of that province who had not seen and heard the gregarious “Joe” and shaken his hand-or been kissed by him if the subject were female, young, and pretty. Yet Howe’s stature had diminished by 1860. He had never duplicated his great triumph, and he had cheapened himself by his constant petitions to the British government for office. Charles Tupper, less flamboyant but a stumper of rare and rude power, was coming to dominate Nova Scotia. Howe needed again to lead a popular cause to restore his ancient glory. It is understandable that he should seek to retrieve fame by opposing confederation, for most Nova Scotians would follow him in this. Jealousy also dressed him for the role;

it is legend in Nova Scotia that when asked why he opposed union, Howe candidly replied that he refused “to play second fiddle to that damned Tupper.” There were more honorable reasons. Howe sincerely believed that the terms of the Quebec Resolutions were a bad bargain for his province, and he resented the trick by which Tupper had sent a delegation to London.

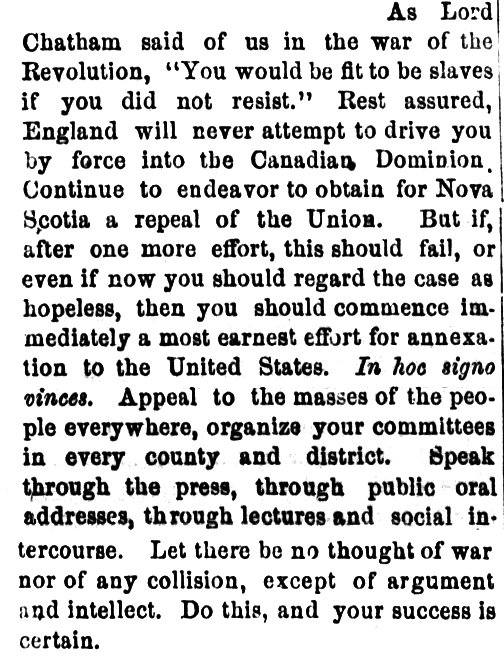

The “antis,” as the opponents of union were called, fought to block confederation in the British Parliament. They formed the League of the Maritime Provinces and sent Howe and others to London under instructions to point out to the Colonial Office that there were “propositions . . . made . . . in the Congress of the United States [which is] publicly entering the field in competition with Canada for the possession of the Provinces.”55 Howe was also to hint that if the Imperial government accepted the federation scheme, there would be “changes which none of us desire to contemplate and all of us deplore.”56

The Nova Scotian delegation was obviously shaking an annexation stick at the British. Howe continued in the same vein by pointing out to the Imperial government the “range of temptation” which political union with the United States offered to the people of the Maritimes: they would have free trade with a market of 34,000,000 people, access to American capital, and the benefit of American fishing bounties.57 But the Colonial

Office was unmoved by intimidation and gave Howe and his delegation no encouragement. He then sought to influence the public and political climate by showering the newspapers and leading men with pamphlets stating Nova Scotia’s case.58

Persuasion was no more successful than threats. The British were inexorably committed to confederation, and talk of annexation entrenched their convictions. Despite the efforts of John Bright and a few others whom Howe had converted, the government pushed the British North America Act through Parliament after a debate less lively than that on a dog tax bill which followed.

But the British had no more succeeded in convincing Howe and his party in Nova Scotia of the sapiency of Imperial policy than he had convinced them of its folly. These opponents of confederation would be heard again, and in unmistakable tones.”

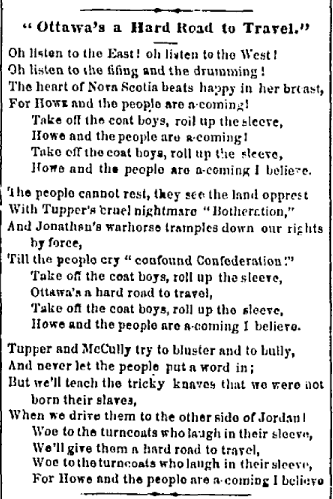

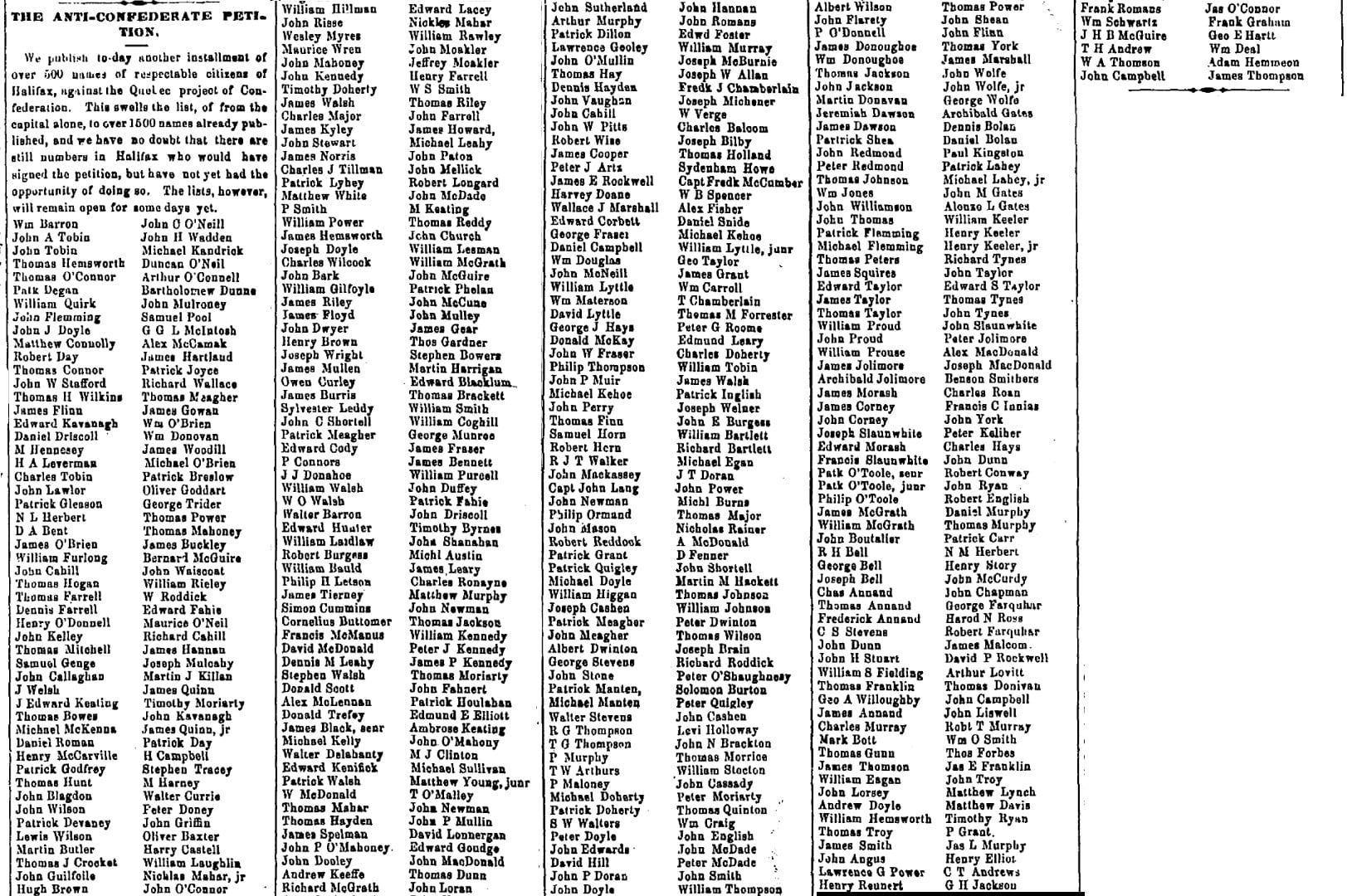

“The opposition to the union in the United States was mildcompared to the distaste with which many in Canada regarded their new country and government. This antagonism, with its accompanying danger to the British connection, was present in Quebec and Ontario, but reached its greatest pitch in Nova Scotia. Here the anticonfederationist leader Howe had warned that his province might seek annexation to the United States if the Imperial government insisted on forcing it into the union. Nova Scotians showed no signs of accepting the Dominion as a fait accompli even after July 1, 1867, when their province became part of the federation. They stubbornly asserted that they would not remain in the union; the equally obstinate British government refused to heed their demands for release from it. A crisis was mounting and a small annexation movement had already made its appearance in the disaffected province.11 Confederation was inducing what it had been designed to prevent, rather than acting as an antidote to it.”

“It is not surprising that the resentment and protest was most acute in Nova Scotia. As already noted, the people of that province had carried their opposition to union to the Crown, only to be spurned. When Joe Howe returned from his fruitless mission to London, he found his province tottering on the brink of disloyalty. He had set a dangerous precedent and course when, in his correspondence with the Colonial Office, he had listed the temptations which annexation offered to his people. The antis of Nova Scotia continued in this direction. Newspapers and public speakers vied with each other in skipping along the verge of treason. Although many of their hints of annexation were attempts to frighten the British government into permitting the secession of the province, some of them were sincere. 17

This incipient annexation movement, however, soon received a check. Most of the antis still looked upon political union with the United States as a last resort and hoped to relieve their distress by other means. These soon seemed to offer. At the first provincial election under the new Dominion, the opponents of confederation achieved a smashing victory. Thirty-six of the thirty-eight members of the provincial assembly were antis, and Tupper was the only unionist among the nineteen members of the federal House of Commons returned from Nova Scotia. This was no victory for annexation. The repealers were confident that their startling success would compel the British government to heed their wishes, and the majority of Nova Scotians still believed that their problems could be solved within the Empire by a return to the status of a separate and self-governing colony. They could restore their old revenue tariff, the income of their government would rise, and no Canadian majority could trample their interests. They also believed that the United States would renew the treaty of 1854 with Nova Scotia alone. This questionable conclusion arose from the dubious assumption that Americans regarded the Canadian economy as competitive with their own, but the Nova Scotian economy as its complement.

So the anti triumph in the election of 1867 convinced Nova Scotians that annexation was unnecessary; they would soon escape the Dominion and return to reciprocity and prosperity. Since secession from Canada was the key which would unlock the door to this pleasant future, the repealers sought to gain it. The provincial assembly passed resolutions requesting the British government to release Nova Scotia from the Dominion, sent

Howe to London bearing this appeal, and awaited confidently for news of their deliverance from the Canadian yoke.

Howe did not share their optimism. His previous mission had taught him that the home government was committed to confederation as the only preventive for annexation.18 If Nova Scotia seceded, New Brunswick would probably follow, and the Dominion would collapse. The Governor General, Lord Monck, had reached the same conclusion. He pressed the colonial secretary to refuse Howe’s request graciously but firmly; if the union broke up, wrote Monck, “I have no hesitation in expressing my opinion . . . that the maintenance of British power or the existence of British institutions in America will soon become impossible.”19 This advice from the man on the spot fortified the determination of the British government to deny the repeal of confederation. As further insurance, the Dominion government sent Charles Tupper to London to counteract the eloquence of his anti rival.

The colonial secretary proved to be courteous in hearing the complaints of Nova Scotia but adamant in refusing to permit its secession.

Early in June, 1868, he informed Monck that the Imperial government could not consider any request for secession; all provincial grievances must and could be redressed within the framework of the Dominion.20 The publication of this dispatch, frustrating their highest hopes, was a terrible shock to the antis. They rained sorrowful and angry denunciations down upon the Canadian and Imperial governments. Many went beyond philippics and vowed that their loyalty was gone. A member of the Dominion Parliament and a former chief justice of Nova Scotia were enthusiastically applauded when they spoke for political union with the United States at a meeting in New Glasgow.21 Other town meetings became forums on annexation.22 The leading paper in the province, the Halifax Morning Chronicle, asserted that “with 30,000,000 of freemen alongside of us, Britain and Canada well

know that they cannot crush Nova Scotia, or force it into a hateful connection.”23 The annexation movement in the province, it was obvious, was waxing as repealers joined its ranks. This sedition was a startling contrast with the past. Nova Scotia had been a devoted colony. The Loyalists who flooded into it after the American Revolution brought with them love of mother country and antipathy to the United States. The Nova Scotians considered themselves a chosen people, and their demonstrations of attachment to the Crown seemed to outdo those of the English themselves. Extreme devotion was followed by immoderate reaction.”

44 Reginald G. Trotter, Canadian Federation, Its Origins and Achievements, (Toronto, 1924), 39-42.

48 These provinces were afraid that Canada would not consent to providing an adequate protection for their fisheries. Moreover, the total population of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. was not equal to that of either Ontario or Quebec.

49 The Canadian tariff averaged 20 percent; that of Nova Scotia, levied principally on luxuries, averaged 10 percent. Joseph Howe Papers, 26, pt I, Miscellaneous Papers on Confederation (Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa).

50 Yarmouth Tribune, June 27, 1866.

54 The American consul at St. John reported that a quarter of the people of the province favored annexation. James Howard to Seward, May 14, 1866, Consular Despatches, St. John, VI, 159.

Curiously, the Fenian raids seem to have promoted the cause of annexation as well as the cause of confederation, for many Canadians who felt that their country was defenseless were ready for “peace at any price.” Monck to Henry Herbert, Earl of Carnarvon, September 28, 1866, G 180 B, Secret and Confidential Despatches, 1856-1866.

55 This is an obvious reference to the Banks bill, described in the next chapter.

56 Instructions to Howe from the League of the Maritime Provinces,

Howe Papers, IV, Letters to Howe, 1864-1873.

57 British Parliament, Accounts and Papers, 1867, XLVIII, 14-15.

58 Howe Papers, IV, 159-86.

11 There were many instances of annexationist activities in Nova Scotia. C. D. Randall to Macdonald, January 7, February 25, 1868, Macdonald Papers, Nova Scotia Affairs, III; Yarmouth Herald, July 18, 1867. Much of the annexationist materials described in this section on Nova Scotia has previously appeared in the author’s article, “The Post-Confederation Annexation Movement in Nova Scotia,” Canadian Historical Review, XXVIII (June, 1947), 156-65. I wish to express thanks to the editor, John T. Saywell, for permission to use the material in this study.

17 Some annexationists were even appealing to the Department of State for assistance in their projects. J. B. Cossitt to Seward, June 20, 1867, Stephen Howard to Seward, March 26, 1867, A. McLean to Seward, June 29, 1867, Miscellaneous Letters to the Department of State, 1867, March II, and June, II.

18 Though outwardly confident, Howe had written gloomy letters to his friends before departing for London. Archbishop T. L. Connolly to Macdonald, October 26, 1867, Macdonald Papers, Nova Scotia Affairs, III; Howe to A. Musgrave, January 17, 1868, Howe Papers, XXXVII, Howe Letter Book.

19 Monck to Richard Campbell Grenville, Duke of Buckingham, February 13, 1868, G 573 A, Secret and Confidential Despatches, 1867- 1869.

20 Buckingham to Monck, June 4, 1868, Macdonald Papers, Nova Scotia Affairs, III. Attempts by John Bright to set up a royal commission of inquiry were defeated, good sign that Howe’s cause was hopeless. Creighton, Macdonald, 17.

21 Yarmouth Herald, August 13, 1868.

22 Connolly to Macdonald, September 16, 1868, Macdonald Papers,

Nova Scotia Affairs, III.

23 Halifax Morning Chronicle, July 11, 1868.

Warner, Donald F. (Donald Frederick). Idea of Continental Union: Agitation for the Annexation of Canada to the United States, 1849-1893. Lexington: Published for the Mississippi Valley Historical Association by the University of Kentucky Press, 1960. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000278662