The fascinating paper traces the constitutional evolution of Nova Scotia, particularly focusing on the role and eventual abolition of its Legislative Council. Established in 1719, the Council initially held executive, legislative, and judicial powers. However, reforms in 1838 separated it into Executive and Legislative Councils. Over time, the Legislative Council became viewed as antiquated, especially post-Confederation when its role diminished due to the Dominion Parliament’s authority over critical matters.

Unlike other provinces, Nova Scotia struggled to abolish its Legislative Council. Attempts were made between 1879 and 1928, led by both Conservatives and Liberals. Premier William Stevens Fielding even appealed to the Queen and Westminster for constitutional amendments. However, Westminster’s refusal and internal disputes prolonged the Council’s existence.

Scholarly research on the Legislative Council is limited, with primary sources such as Assembly and Council debates only available up to the mid-1920s. This lack of documentation complicates understanding the Council’s history. Additionally, crucial records from the Office of the Attorney General are missing, further hindering research efforts.

The Nova Scotian constitution relied heavily on royal prerogative, with the Legislative Council’s structure evolving over time through various commissions and instructions. Despite reforms, recruiting and retaining members remained challenging due to unpaid positions and vague tenure rules.

A significant reform occurred in 1925, limiting Councillors’ tenure and setting an age limit. Premier Armstrong’s bill aimed to modernize the Council, but it faced opposition from other parties, leading to heated debates.

The Supreme Court’s decision in 1926 regarding the Council’s constitution was inconclusive, prompting Premier Rhodes to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Privy Council’s ruling in 1927 validated the Lieutenant-Governor’s power to abolish the Council, ending its existence.

The text highlights the complexities of Nova Scotia’s constitutional history and the challenges in understanding and documenting its evolution. Premier Rhodes’s determined efforts ultimately led to the Legislative Council’s demise, challenging long-held constitutional conventions in the process.

“From the origins of British government in Nova Scotia, there had been a council. The first, established in 1719, combined the roles of cabinet, court of appeal, and upper house of the provincial Legislature. Known simply as the Council or the Council of Twelve (for the twelve members of which it was customarily composed), it came under increasing attack. In 1838, the British Government, finally giving in to popular demands for reform, split the Council of Twelve into separate Executive and Legislative Councils (the judicial functions having for the most part earlier been transferred to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia). Although the Legislative Council was initially accepted as an integral component of Nova Scotia government, as decades passed it came to be seen as increasingly antiquated and unnecessary, especially after Confederation transferred many of the most important (and controversial) concerns to the Dominion Parliament. While an appointed upper house might have served an important role when the Nova Scotia Legislature had to face questions of international trade, national defence, criminal justice, and navigation, it seemed an extravagance when the Legislature’s jurisdiction had been circumscribed to matters such as education, public health, and management of public lands.”

“While other Canadian provinces had also had Legislative Councils, none found it as difficult to achieve abolition. New Brunswick’s Legislative Council was abolished within the ten years of the Andrew Blair administration (1882-1892) after Blair decided to delay any appointments to the Council until a majority of pro-abolition members could be named all at once. Prince Edward Island, which had experimented with an elective Legislative Council, merged the two houses of its legislature in 1893, with half elected as assemblymen (by the electorate at large) and half councillors (by landowners). Manitoba’s Legislative Council, which had existed for only a brief six years, was abolished in 1876 after the Dominion government refused to subsidize the province unless it cut expenditures, the majority of which were spent on maintaining the Legislature. The Legislative Council of Québec, which survived forty years longer than Nova Scotia’s, did not come under serious critique until the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s; although it initially refused to abolish itself and the provincial government petitioned Westminster to amend the British North America Act to remove the upper house, the Council ultimately agreed when the the Union Nationale government offered to pay annual pensions to the councillors. Other provinces lost their Legislative Councils at the same time as broader constitutional changes: the Colony of Vancouver Island lost its Council during its merger with mainland British Columbia; Ontario was created without a Council, though it had previously had one as part of the Province of Canada; and Newfoundland, which had a Council prior to the suspension of responsible government in 1933, lost it upon joining Canada in 1949. Nova Scotia, however, was different. For the better part of half a century, from 1879 to 1928, the Province sought to abolish its Legislative Council without success, with only a brief period of quiescence in the first decade of the Twentieth Century. Initially championed by Conservatives, Liberals soon jumped onto the abolition bandwagon, with Premier (and later federal Finance Minister) William Stevens Fielding submitting an address to the Queen asking for an amendment to the British North America Act to accomplish what was seen as otherwise impossible. It was only after Westminster refused to act that Nova Scotia’s political elite grudgingly accepted the Council’s continued existence. But even this temporary ceasefire would shatter with the passage of the imperial Parliament Act, 1911.”

“Very little scholarship relating to the Legislative Council exists from the period prior to abolition. The most significant was a presentation by constitutional scholar John George Bourinot during the 1896 annual meeting of the Royal Society of Canada. The presentation, entitled “Some Contributions to Canadian Constitutional History: The Constitution of the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia”, focused largely on the Commissions and Instructions of Nova Scotia’s colonial governors, but ultimately shifted to the effects of the 1845-46 correspondence between the Colonial Office and the Legislative Council. In Bourinot’s view, the 1845-46 correspondence was a moral contract between the sovereign and the Legislative Council, which had become a customary part of the Province’s constitution; but, while the changes wrought were as much a part of the constitution as the recognition of responsible government, Bourinot recognized they were just as unenforceable in court. Somewhat surprisingly given his stature in late Nineteenth- Century constitutional law, his article was not referenced directly in either of the court decisions concerning the Legislative Council’s constitution, nor in the 1926-1928 abolition debates; either his article had been forgotten in the intervening years or neither side in the debate viewed it as helping their cause significantly, as it argued the Councillors’ tenure was for life under constitutional convention, but that that convention could not be enforced in court.”

“Of much greater concern was the disappearance or non-existence of key primary sources. As my research was to focus largely on the arguments raised in the legislative debates, I naturally turned to the printed House of Assembly and Legislative Council debates. Unfortunately, I soon discovered that Nova Scotia had ceased publication of the Assembly debates after 1916 and the Council debates after 1922, with publication picking up only in the 1950s. There were thus no published legislative debates from which I could draw these competing discourses. Fortunately, the Halifax newspapers of the era were generally very good at covering any Assembly debates considered “important”; the abolition of the Legislative Council, a major change to the provincial constitution, was seen as important, and the debates were covered regularly and in fair depth. However, neither the Halifax Herald nor the Morning Chronicle (later the Halifax Chronicle) published anything that could be considered authoritative; both papers had strong partisan biases (the Herald being connected with the Conservative Party and the Chronicle with the Liberals), meaning information was emphasized or left out depending on how it fit the papers’ agendas. Moreover, if something else important was taking place, the papers would dedicate far less time to the Council question. (During the first World War, for instance, the debates on reforming the Legislative Council were barely covered by either paper, which instead focused almost exclusively on news from the front; there is thus almost no record of the 1917 constitutional crisis.) Thus while the Herald and Chronicle provided significant records of the abolition debates, they had to be considered in tandem in order to arrive at something approaching the real turn of events. In effect, I was forced to reconstruct the legislative debates from the incomplete reports of two biased newspapers. This reconstruction was made all the more difficult by the fact that neither paper is indexed or is available online; I have thus been required to review on microfilm the entire run of each paper during the months when the Nova Scotia Legislature was in session, looking for any article, editorial, or letter to the editor that might be related to the Legislative Council. (In the case of the Herald, I reviewed the entire run from January 1925 through March 1928.)

To make matters worse, very few documents relating to Legislative Council abolition have been maintained in archives or governmental files. Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management (NSARM, previously the Public Archives of Nova Scotia) was established by an act of the Legislature in 1929, the year after the Legislative Council was abolished. While NSARM holds a fairly comprehensive collection of Premier Edgar Nelson Rhodes’ papers from late 1927 on, there are substantial gaps in the earlier period of his premiership (beginning in mid-1925). As such, Rhodes’ papers provide fairly comprehensive coverage of the Legislative Council’s final days, after the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council decision, but there is very little regarding Rhodes’ decision to push for abolition, his negotiations with the Councillors in 1926-1927, his efforts to appoint in excess of twenty one Councillors in March 1926, or the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia decision and appeal to the Privy Council. While disappointing, these gaps in Rhodes’ files might not have been critical but for the disappearance of other materials, notably the records of the Office of the Attorney General. NSARM’s catalog lists among the Attorney Generals’ files a folder identified “Legislative Council: re: legal matters, appointments, 1926-40”. Unfortunately, when I requested this file, I was informed that it had been missing since at least 1982, when NSARM moved into its present location. While the archivists were kind enough to attempt to locate the folder in other areas (e.g., RG10 F44), it was not and may never be located. As such, what may have been the best compilation of materials relating to the Legislative Council litigation, carefully collected into a single location for future researchers, is lost and inaccessible. Other materials, while theoretically in existence, have proven inaccessible for other reasons.”

“Unlike the Canadian federal government or the governments of Ontario, Quebec, and other provinces created in or after 1867, there is no single document or set of documents to which one can look to ascertain the Nova Scotian constitution. While the British North America Act, 1867, included detailed constitutional provisions on the governments of Ontario and Quebec, the constitution of Nova Scotia continued as it existed prior to Confederation, except insofar as it was changed by the British North America Act itself:

“The Constitution of the Legislature of each of the Provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick shall, subject to the Provisions of this Act, continue as it exists at the Union until altered under the Authority of this Act.”

Moreover, unlike many of the colonies of the First British Empire, Nova Scotia was not granted a colonial charter establishing the terms of its government. Instead, Nova Scotia’s constitution was based largely on royal prerogative, as expressed in the Commissions and Instructions presented to the Province’s pre-Confederation Governors. The British North America Act attempted to set into stone Nova Scotia’s prerogative constitution, as it existed at the time of Confederation. But, what did that mean? A prerogative constitution implied one that could be changed by the Sovereign, yet the British North America Act suggested the constitution was locked in place. Did the British North America Act remove prerogative—that is, eliminate the Sovereign’s ability to change the constitution of the Province at will—or did it merely state that the provincial constitution would continue to be built upon sand until affirmative action by the Nova Scotia Legislature? For almost sixty years after Confederation, the predominant view in Nova Scotia was that the British North America Act had, indeed, locked the Province’s constitution in place, so that it could no longer be changed by simple prerogative. Instead, the royal prerogative to amend the constitution had been delegated to the Nova Scotia Legislature. This view would only unravel slowly, as the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council recognized the continuing role of prerogative in the provincial constitutions. In order to understand these later debates, however, we must first examine the origins of Nova Scotia’s prerogative constitution, particularly those provisions relating to the Legislative Council.

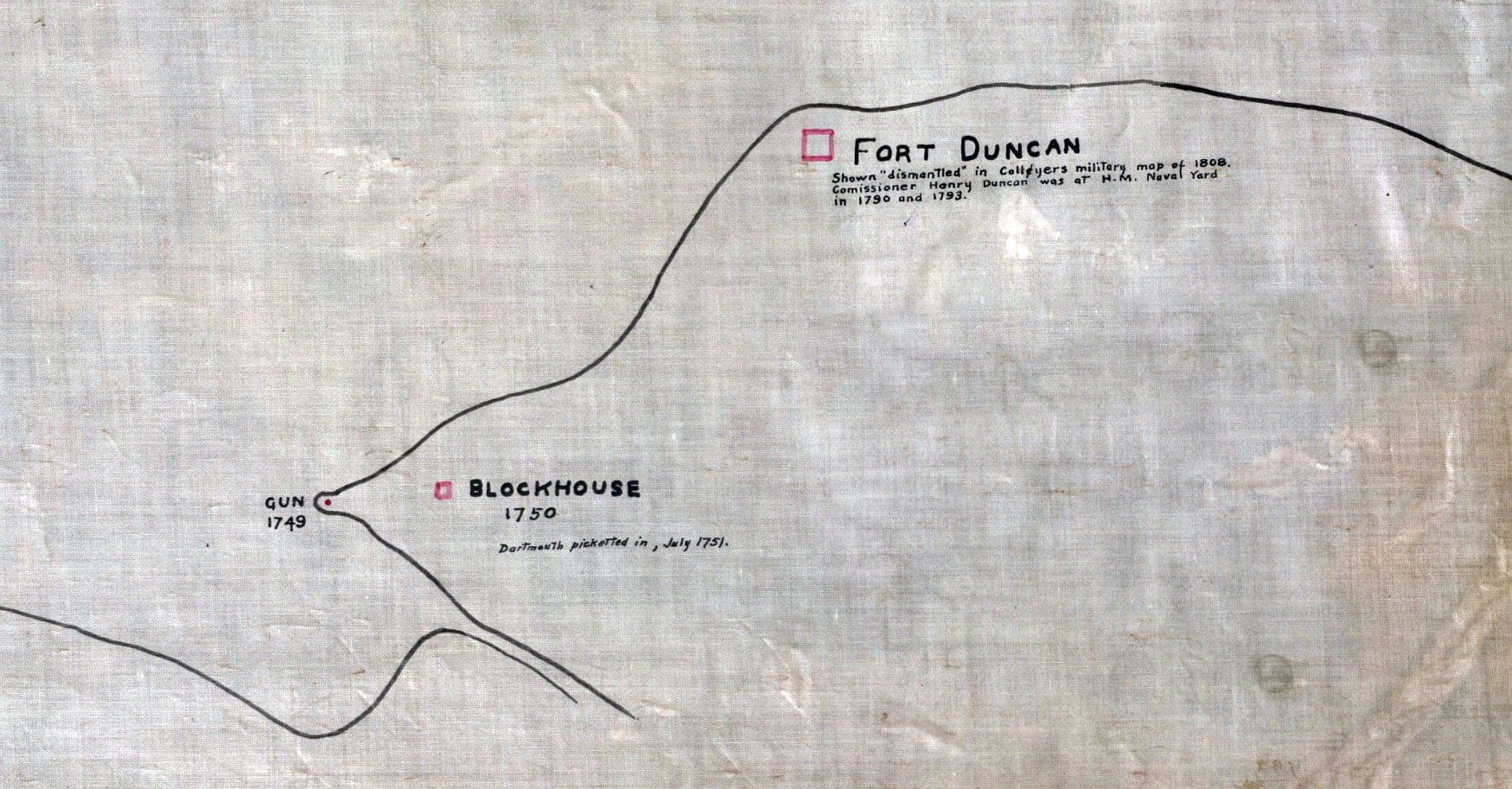

Depending on how one views the issue, the Legislative Council dated back to 1719 (the first Council, which combined executive, legislative and judicial functions), 1838 (the split of the earlier Council of Twelve into separate Legislative and Executive Councils), or 1861 (the reformation of the Legislative Council in Governor-in-Chief Monck’s Commission of office). The original Council (generally known as the Council of Twelve) dates to 1719, when it was created pursuant to the Commission and Instructions given to Richard Philipps, third Governor of the newly-acquired Province of Nova Scotia. Philipps’ original Commission, dated July 1719, authorized him “to appoint such fitting and discreet persons as you shall either find there or carry along with you, not exceeding the number of twelve, to be our Council in the said province, till our further pleasure be known, any five whereof we do hereby appoint to be a quorum.” Upon arriving in Nova Scotia in April 1720, Philipps did just that, appointing a council “consisting of himself and eleven officers and townsmen.” This initial Council of Twelve consisted primarily of military officers, as there were as yet few British settlers and the Acadians were not seen as appropriate for appointment. For similar reasons, Philipps did not call an Assembly, though he had been instructed to do so in his Commission, and legislation for the Province was impossible in its absence. In the meantime, Philipps’ commission stated that he could refer to the Instructions to the governor of Virginia, which provided something of a framework for government in the absence of an Assembly or formal charter.”

“When the seat of government was moved from Annapolis Royal to Halifax under Governor Edward Cornwallis, the Council of Twelve was reconstituted with new membership and a slightly modified constitution. Cornwallis and his successors could now appoint provisionally up to nine Councillors.

In 1764, the Commission appointing Governor Montagu Wilmot would also limit the time Councillors could be out of the Province without the consent of the Governor or Sovereign to six months and one year, respectively. Neither reform, however, seems to have eliminated the problems with maintaining quorum. When the Council of Twelve did operate, it exercised executive, judicial, and (after 1758) legislative powers. In addition to acting as Nova Scotia’s cabinet (with members typically serving in such roles as Chief Justice, Provincial Secretary, Treasurer, Surveyor- General, or Attorney General), the Council also acted as the Province’s General Court, which had original jurisdiction in criminal cases and appellate jurisdiction in civil matters concerning a dispute over £300. This judicial function was reduced, but not wholly eliminated, upon the creation of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia in 1754. Finally, after the first Assembly was finally called in 1758, the Council acted as the Upper House of the Legislature, and would frequently amend or refuse its assent to legislation with which the Councillors did not agree, especially any and all attempts to increase the powers of the Assembly at the expense of the Council.”

Although the 1837-38 reforms created a more modern Legislative Council, better positioned to act as an independent chamber of sober, second thought, it still proved difficult to recruit Councillors, especially from outside of Halifax. Members of the Council of Twelve had never been paid for their service as Councillors (though most held executive or judicial office that came with some manner of reimbursement); the tradition of an unpaid Council continued post-reform. As such, any potential members would have to be wealthy enough to afford to take off several weeks at a time for legislative sessions, and, if they lived outside of Halifax, pay for travel, room and board. Prospective Councillors were also turned off by the lack of secure tenure and the ill-defined nature of the Legislative Council’s constitution. In response to the perceived difficulty in recruiting and maintaining strong candidates, on March 18, 1845, the Council formed a committee of five members to consider the issue and report back with recommendations. On April 7, the committee proposed an address to Queen Victoria, to be delivered via Lieutenant-Governor Falkland and the Colonial Office, laying out the difficulty and requesting either that Councillors be compensated for their work or that the Council be given a defined constitution:

Seats in the Legislative Council are among the most honorable Colonial distinctions in the gift of Your Majesty, yet it is with difficulty that Gentlemen can be induced to accept them, or if they do, a speedy resignation or partial attendance exhibit the estimation in which the Body itself, and the Office of a Legislative Councillor are held. Whether these results may be ascribed to the want of a defined Constitution, or of a pecuniary provision for the expense of the attendance of the Country members at the Legislative Sessions, will be for Your Majesty’s gracious consideration. . . . In regard to a matter in which your personal wishes and feelings may influence their judgment, they [the Councillors] do not presume to suggest what steps should be taken, but humbly and earnestly pray that Your Majesty would adopt such measures as seem proper for establishing this Branch of the Legislature upon such a basis as may be compatible with the right, efficient, and independent discharge of its high and important duties.”

“Post-Confederation, there was only two significant amendments to the constitution of the Legislative Council. First, in 1872, the power to appoint Councillors was vested wholly in the Lieutenant-Governor in the name of the Crown. No longer would it be necessary to make “provisional appointments,” which would later be approved or denied by the Queen. In addition to greatly streamlining the appointment process and removing a step seen as wholly unnecessary in the new political context, the reform also removed any constitutional concerns about the Sovereign’s ability to act at all on a matter of provincial or Dominion concern post-Confederation.”

“The second major amendment to the Legislative Council’s constitution came in 1925, at the tail end of forty-three years of Liberal rule and four years of discussions between the Assembly and Council. After repeated efforts to abolish the Council had failed, Premier Armstrong and the Liberals instead proposed reforming it, and, surprisingly, the Council agreed. On April 6, 1925, Armstrong introduced his reform bill, which echoed the reforms of the Parliament Act, 1911, while also limiting the tenure of office of newly-appointed Councillors to ten years and establishing an upper age limit for members (75 for existing members and 70 for new members); until reaching the maximum age, however, Councillors could be reappointed when their terms expired. The Morning Chronicle largely praised the bill, though it did suggest removing the provision allowing for reappointment. In particular, the Chronicle lauded the reasonableness and non-radical nature of the reform, which changed the Council insofar as it was necessary. It does not propose to impair extensively or undesirably, much less to override, the essential present powers of the Council. It does not propose to alter, except by amendments, its membership. It is merely intended to provided that the fixed and determined will of the elected representatives of the people shall ultimately prevail over persistent opposition of the non-elective House, after due delay for reflection and re- consideration. The power of the Upper House to check and correct hasty legislation and enforce due discussion is to be left practically unimpaired, while a means to overcome factious or unwarranted opposition from the Council is to be provided. If anything, the Chronicle suggested the reform might be too radical, as the emasculated state of the House of Lords had been criticized in Britain. Other parties were less supportive of the reform proposals. The Farmer-Labor coalition, which had swept into the role of Opposition after the 1920 election, opposed reform on principle. D.G. McKenzie, Leader of the Opposition, for instance, condemned Armstrong’s bill, saying that the province needed “a responsible government” and that it would be better to abolish the Council or make it an elective body than to fill it with defeated Liberal candidates. The three Conservatives in the Assembly also opposed the bill despite party leader William Lorimer Hall (who did not hold a seat in the Assembly) having introduced a very similar bill in 1916.”

“The (Tenure of office) Bill inspired a Liberal uproar. The Morning Chronicle called it “the hand of Tammany,” referring to the still-powerful Tammany Hall political machine that dominated New York City politics from the 1850s through 1930s.”

“In reply to claims that the Council would protect the province from ill-drafted legislation, he cited an example from the 1922 Session in which two inconsistent acts were passed in regards to the rules of the road, without anyone in the Council having noticed (though, admittedly, the error was made by the Assembly); in order to rectify the error without calling a special session of the Legislature, the Liberal government petitioned Ottawa to disallow the statute. According to Rhodes, if the Council could not catch such an obvious error in legislation—“any child could have discovered the inconsistency”—then contrary to the Liberals’ claims, the Council did nothing to correct “hasty legislation.” Instead, having a second chamber encouraged the Assembly to be lazy in drafting legislation. After Chisholm compared the Council to the Canadian Senate, which the Fathers of Confederation had endorsed, Rhodes repeated his earlier defence of the Senate, emphasizing Nova Scotia’s disproportionate representation. But where the Senate dealt with important national issues, such as foreign relations and war, the Council faced no issues of such great importance. Indeed, most other provinces had found their upper houses unnecessary. Rhodes then audaciously expanded his argument into a belittling of Nova Scotian government, stating, “With a population less than Toronto we have trimmed ourselves with all the legislative attributes of a nation. I venture to say that the people of this province would be well advised if this chamber were reduced to 30 members instead of 43 as at present. To my mind there is no reason why this should not be brought about.” In Rhodes’ eye, the trappings of the Nova Scotia government, including the Legislative Council, were undeserved and unneeded.”

[This argument, “with a population less than Toronto”, is still used today to push any number of unilateral constitutional changes to bring about “greater efficiency”, which is usually code for a dictatorial action to support a specific party or to install a mechanism used to sever an accountability framework (such as municipal amalgamations, dissolutions of grand juries and local courts, dissolution of elected school boards and local health boards, all achieved by fiat].

“Three months later, on October 23, 1926, the Court delivered its decision, such as it was. For all practical purposes, the Court was evenly divided, with Chief Justice Harris and Justice Chisholm holding that the Lieutenant-Governor could appoint in excess of twenty- one members to the Council, and that members held their positions during the pleasure of the Lieutenant-Governor. By contrast, Justices Carroll and Mellish held that the Council was capped at twenty-one, absent a formal amendment to the provincial constitution, and that tenure, if at pleasure, was at the pleasure of the Crown acting by and with the advice of the imperial cabinet (Carroll and Mellish disagreed on whether tenure was at pleasure (Carroll) or for life (Mellish)). Thus with only two exceptions, there could not be said to be a “decision” of the Court, as it was on most issues evenly divided.”

“Almost immediately after the decision was rendered, Premier Rhodes stated that he intended to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. In response, the Councillors, initially through the Morning Chronicle and later through legal counsel, argued that appeal was inappropriate, as the Supreme Court had not actually reached a decision. If there was no decision, asked the Morning Chronicle, how could there be an appeal to a higher court? While the Chronicle recognized there might be some technical way out, it argued that the better approach was to reargue the case in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia before a panel of five or seven judges, in order to ensure a majority decision.”

“On October 18, 1927, the waiting finally came to an end, as the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council released its judgment. In a brief fifteen paragraphs, the Privy Council found for the Province on all four questions, finally opening the door for Rhodes to abolish the Legislative Council at the next session of the Legislature. It would be strange indeed for the Nova Scotian Fathers of Confederation to have intended to create a toothless Legislative Council that could be abolished or whose members could be dismissed at any time; if that had been the intent, why not simply abolish the Council as part of the British North America Act? Moreover, both the plan of Confederation and the 1873 Act were approved by the Legislative Council, which presumably would have rejected either if it believed it meant signing its own death warrant. The semi-anonymous author (“J.E.R.”) of a Canadian Bar Journal “Case and Comment” on the Privy Council decision agreed:

The theory [that all prerogative powers had been transferred to the Lieutenant-Governor] is in itself not free from difficulty. Its acceptance gives to the B.N.A. Act an effect that certainly would have shocked the ‘Fathers of Confederation.’ A persual of the various drafts of sections dealing with the constitutions of the legislatures of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick discloses a clear intention that the N. S. Legislature should retain its constitution with restricted legislative powers. If there had been any suggestion, that the result would have been a second chamber, completely dependant upon the House of Assembly, whose members would always be subject to the threat of dismissal if they dared to disagree with the views of the lower house, it is unlikely that the concurrence of the Nova Scotia Legislature would have been obtained. Their Lordships refer to the anomaly of appointments made in Halifax being revoked in London but there is no doubt that the so-called anomaly was the result actually contemplated.”

“Just six months after the Legislative Council disappeared forever, Nova Scotians returned to the polls. Though Rhodes had not thought it necessary to consult the electorate on changing the provincial constitution by abolishing the Council, he argued in September 1928 that the members of the Assembly should face the voters before making use of their substantial new powers. That is, changing the constitution did not require an election, but using the powers resulting from that changed constitution did.”

“This constitutional conundrum—the Legislative Council’s consent was required to abolish the Legislative Council—appeared for decades to be unresolvable. Successive governments sought to achieve abolition through some alternative means, whether it be an amendment to the British North America Act, requiring appointees to pledge themselves in favour of abolition, or offering substantial pensions, but none were successful. Eventually, the governing Liberals effectively gave up, embraced the Council, and sought reform instead of abolition. But decades of criticism left a Council bereft of popular support. When Edgar Nelson Rhodes took office, he recognized the Council as a vestige of the old regime, an independent source of authority that could block his legislative agenda (even if that authority was mostly unexercised). Rhodes thus launched a renewed battle against the Council, dedicated this time to destroy it once and for all. In doing so, Rhodes questioned decades-old assumptions about the nature of the provincial constitution and the role of the Council. When Lieutenant-Governor Tory and the Dominion Law Officers were unwilling to go through with his plans to pack the Council with Conservative appointees, he took the matter to court. Fortunately for Rhodes, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council was unwilling to recognize the settled conventions on which so much of Nova Scotian practice was based. According to the Privy Council, the Legislative Council was built on a foundation of sand.”

“While the Privy Council’s decision verified that Lieutenant-Governor Tory had the ability to act, it in no way mandated his actions. Indeed, use of the prerogative powers of the Sovereign to dismiss Councillors or to appoint in excess of twenty-one members violated constitutional convention in place since at least 1846. True, these conventions did not have the binding force of law, but this did not make them any less a part of the constitutional structure of the Province.”

Hoffman, Charlotte, The Abolition of the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia, 1925-1928 (December 7, 2011). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2273029 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2273029