Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane. Bye-laws of the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane, 1868. [Halifax, N.S.: s.n.], 1868. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/aeu.ark:/13960/t9184245w

1860s

Canadian confederation, information in relation to petition of Nova Scotia delegates

“The scheme for confederating the provinces took its rise in Canada…”

Canadian Confederation: Information In Relation to Petition of Nova Scotia Delegates. [S.l.: s.n., 1866.] https://hdl.handle.net/2027/aeu.ark:/13960/t45q6422g

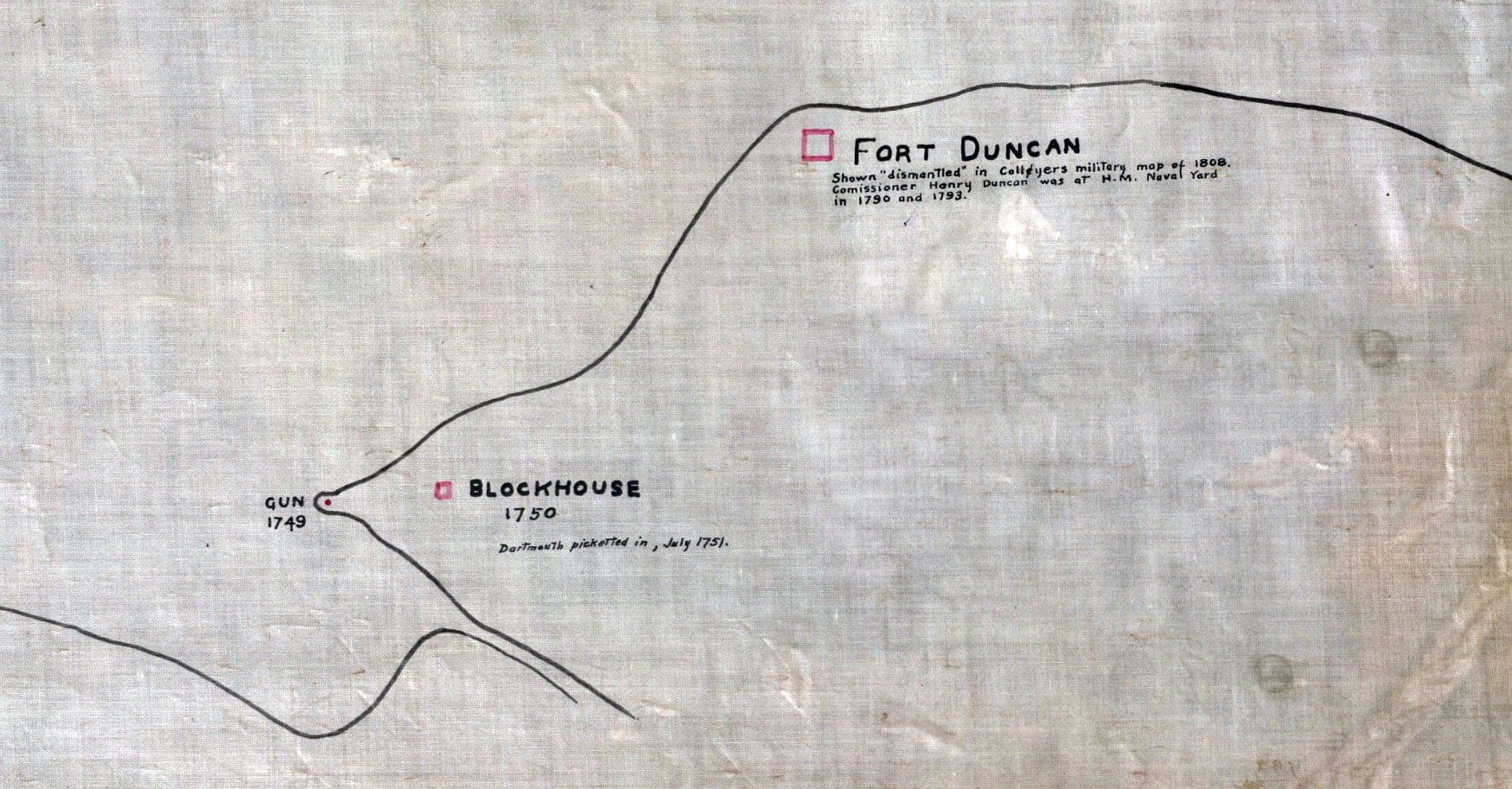

Fortifications (in Dartmouth)

Fort Duncan: Shown “dismantled” in Collyers military map of 1808. Commissioner Henry Duncan was at H.M Naval Yard in 1790 and 1793.

Blockhouse: 1750. Dartmouth picketed in, July 1751.

Gun: 1749.

Eastern Battery, Fort Clarence: 1754. Freestone tower there in Jan 1810 & in 1834. Tower removed about 1865, when new works were begun. Fort Clarence reconstructed 1865 to 1868 (Mil. recds). Site sold to Imperial Oil Co, 1927. Known as Eastern Battery in 1786.

“Halifax Fortifications”, 1928. https://archives.novascotia.ca/maps/archives/?ID=1443

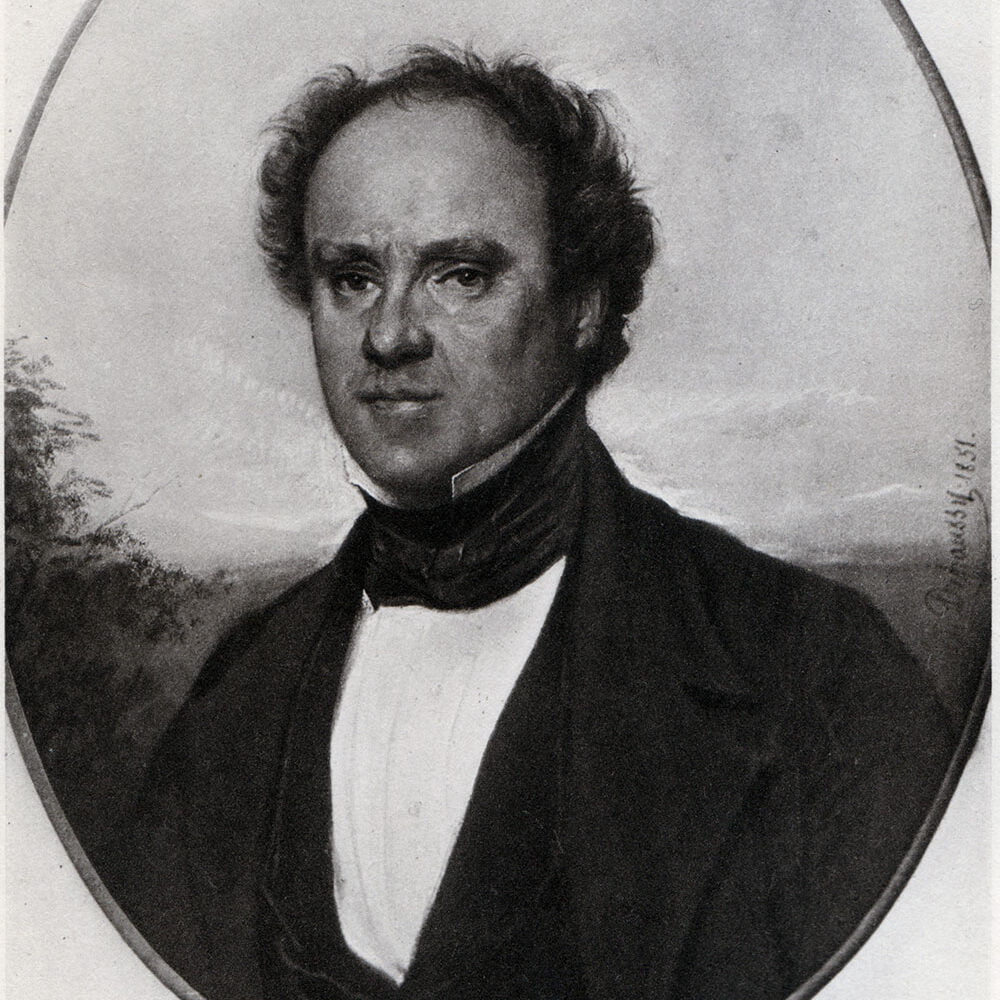

Speech in favor of repeal, January 13th, 1868

“Let me say in conclusion that I have not instigated these meetings. Every action taken in Nova Scotia will in some quarters be attributed to me, and we will be told that the feeling is the result of my organized agitation. I had scarcely got home to Dartmouth when I got an invitation to attend the meeting there. This meeting sprung from the simultaneous feeling of the community, and it would be a great mistake to suppose that that feeling, in all its depth and strength, originates in the intellectual action of one man. If I had been drowned on my passage from England, the electoral returns would hardly have been reduced by a single seat; if I were to die tomorrow the people of Nova Scotia would go on with steady, steadfast roll of thought in this highly intellectual struggle for freedom.”

Howe, Joseph. Annand, William. Chisholm, Joseph Andrew. “The Speeches and Public Letters of Joseph Howe” Halifax, Canada: The Chronicle publishing company, 1909. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b724784?urlappend=%3Bseq=553

Speech at Dartmouth, May 22 1867

Joseph Howe’s Speech at Dartmouth, May 22nd, 1867, is a passionate lamentation, decrying the loss of Nova Scotian autonomy and self-governance to the Canadian government through confederation. He reminisced about the struggles over decades for self-government fought against British control, highlighting the achievements in areas such as governance, trade, taxation, militia organization, postal services, currency stability, banking, and savings institutions.

“The rifle is the modern weapon, and our people have not been slow to learn the use of it. Organized by their own Government, commanded by their friends and neighbours, 50,000 men have been embodied and partially drilled for self-defence. But now strangers are to control this force—to appoint the officers and to direct its movements.“

He expressed deep concern that these hard-won freedoms and systems were being eroded by the Canadian government, distant and uncaring, imposing its will on Nova Scotia without regard for its unique needs and experiences. He viewed the impending loss of control over crucial aspects of governance, economy, and finance as a betrayal, fearing increased taxation, economic instability, and exploitation of the populace by external interests. All of which came to pass.

“But it is said, why should we complain? We are still to manage our local affairs. I have shown you that self-government, in all that gives dignity and security to a free state, is to be swept away.

The Canadians are to appoint our governors, judges and senators. They are to “tax us by any and every mode” and spend the money. They are to regulate our trade, control our Post Offices, command the militia, fix the salaries, do what they like with our shipping and navigation, with our sea-coast and river fisheries, regulate the currency and the rate of interest, and seize upon our savings banks.

What remains? Listen, and be comforted. You are to have the privilege of “imposing direct taxation, within the Province, in order to the raising of revenue for Provincial purposes.” Why do you not go down on your knees and be thankful for this crowning mercy when fifty per cent has been added to your ad valorem duties, and the money has been all swept away to dig canals or fortify Montreal.”

Howe, one of our leading statesman and also, it appears, our prognosticator in chief, painted a vivid picture of a once-independent Nova Scotia being subjugated and marginalized within the larger Canadian federation, and the dire consequences for its economy, society, and autonomy that would result.

In opposing the British North America Act… (Joseph Howe) always urged that it was not acceptable to the people of Nova Scotia. As an election was soon to be held, to make good his statement Mr. Howe felt that he must organize his forces, and demonstrate beyond dispute that the Province of Nova Scotia was overwhelmingly opposed to the union. He returned early in May, and on May 22nd delivered at Dartmouth the following speech, in which he betrays no loss of his old-time warmth and vigour:

MEN OF DARTMOUTH —

Never, since the [Mi’kmaq] came down the Shubenacadie Lakes in 1750, burnt the houses of the early settlers, and scalped or carried them captives to the woods, have the people upon this harbour been called upon to face circumstances so serious as those which confront them now. We may truly say, in the language of Burke, that “the high roads are broken up and the waters are out,” and that everything around us is in a state of chaos and uncertainty. A year ago Nova Scotia presented the aspect of a self-governed community, loyal to a man, attached to their institutions, cheerful, prosperous and contented. You could look back upon the past with pride, on the present with confidence, and on the future with hope.

Now all this has been changed. We have been entrapped into a revolution. You look into each other’s faces and ask, What is to come next? You grasp each other’s hands as though in the presence of sudden danger. You are a self-governed and independent community no longer. The institutions founded by your fathers, and strengthened and consolidated by your own exertions, have been overthrown. Your revenues are to be swept beyond your control. You are henceforward to be governed by strangers, and your hearts are wrung by the reflection that this has not been done by the strong hand of open violence, but by the treachery and connivance of those whom you trusted, and by whom you have been betrayed.

The [Mi’kmaq] who scalped your forefathers were open enemies, and had good reason for what they did. They were fighting for their country, which they loved, as we have loved it in these latter years. It was a wilderness. There was perhaps not a square mile of cultivation, or a road or a bridge anywhere. But it was their home, and what God in His bounty had given them they defended like brave and true men. They fought the old pioneers of our civilization for a hundred and thirty years, and during all that time they were true to each other and to their country, wilderness though it was. There is no record or tradition of treachery or betrayal of trust among these [Mi’kmaq] to parallel that of which you complain.

Let us, in imagination, do them the injustice they do not deserve, and assume that six of their young men went over and sold them to the Milicetes of New Brunswick or to the Penobscots of Maine. What would have happened? Would the old men, on their return, have folded them to their bosoms, or the young braves have trusted them again? No,—the tomahawk and the fire would have been their reward, and the duty of honour and good faith would have been illustrated by a terrible example. The race is mouldering away, but there is no stain of treason on its traditions. Even in its day of decadence and humiliation it challenges respect, and when the last of the [Mi’kmaq] bows his head in his solitary camp and resigns his soul to his Creator, he may look back with pride upon the past, and thank the “Great Spirit” that there was not a Tupper or a Henry, an Archibald or a McCully in his tribe.

Look again at that dreary and uncertain hundred and thirty years which preceded the foundation of Halifax, which Beamish Murdoch (whose book it always gives me pleasure to recommend) so carefully delineates, and you will find that even among the earlier explorers and occupants of our western counties, fitful and uncertain as were their fortunes, there were fidelity and honour. When Halifax and Dartmouth were founded, when there were but a few thousand men upon this harbour, living within palisades and defended by block-houses—when an impenetrable wilderness lay behind them, and the woods were full of [Mi’kmaq] and of French, we hear of no treachery, of no betrayal of trust.

The “forefathers of our hamlets” were true to each other. They toiled in the belief that they were founding a noble Province that their posterity would govern. The loyalists, who came in great numbers during the revolutionary war, cherished the same belief, and never dreamed that the Province they were strengthening by their intelligence and industry was to be wrested from their descendants and governed by Canadians. The Scotch emigrants who flowed into our eastern counties came, attracted by a name they loved, to govern themselves, and transmit the country untrammelled to their descendants. The Irish, fleeing from a land that had been swindled out of its legislature, fondly believed that here they would find the freedom and the self-dependence they had sighed for at home. For ninety years all these industrial, intellectual and social elements, fusing into an active and high-spirited community, were led and guided by able and patriotic men, now no more.

In fancy I can see them ranged around me in a noble historic gallery—Colonel Barclay and Isaac Wilkins, Sampson Salter Blowers, Foster Hutchinson, and many others. Was there one among them all who would have sold his country? Coming down to a later period, we find men of whom we are not ashamed. We are sometimes told that small countries produce small men, but John Young, Robie, Fairbanks, Bliss, Doyle, Huntington, Uniacke, Bell, in breadth of view, brilliancy and knowledge were the equals of the best that Canada ever produced. Which of these men would have sold Nova Scotia, or delivered her over, bound hand and foot, without the consent of her people to the government of strangers? There is not one whose picture would not start from the wall, whose bones would not rattle in the grave, at the very suspicion.

Sir, there is one name, that of S. G. W. Archibald, that among this fine fraternity is invested with a rare lustre in comparison with the recent achievement of one who has earned unenviable notoriety. When the rights and powers of our Parliament were menaced he defended them, and even though the immediate matter in dispute was but 4d. a gallon upon brandy, like the ship-money of old, it involved a principle, and Archibald defended the rights of the House, and the independent action in all matters of revenue and supply of the people of Nova Scotia. Gratefully is the act remembered, and now that we have seen all our revenues and the united power of taxation transferred to strangers, is it surprising that we should wish that the person who has perpetrated this outrage should have found another name?

The old men who sit around me, and the men of middle age who hear my voice, know that thirty years ago we engaged in a series of struggles which the growth of population, wealth and intelligence rendered inevitable. For what did we contend? Chiefly for the right of self-government. We won it from Downing Street after many a manly struggle, and we exercised and never abused it for a quarter of a century. Where is it now? Gone from us, and certain persons in Canada are now to exercise over us powers more arbitrary and excessive than any the Colonial Secretaries ever claimed. Our Executive and Legislative Councillors were formerly selected in Downing Street. For more than twenty years we have appointed them ourselves. But the right has been bartered away by those who have betrayed us, and now we must be content with those our Canadian masters give. The batch already announced shows the principles which are to govern the selection.

For many years the Colonial Secretary dispensed our casual and territorial revenues. The sum rarely exceeded £12,000 sterling, but the money was ours, and yielding at last to common sense and rational argument, our claims were allowed. But what do we see now? Almost all our revenues—not twelve thousand but hundreds of thousands—are to be swept away and handed over to the custody and the administration of strangers.

The old men here remember when we had no control over our trade, and when Halifax was the only free port. By slow degrees we pressed for a better system, till, under the enlightened commercial policy of England, we were left untrammelled to levy what duties we pleased and to regulate our trade. Its marvellous development under our independent action astonishes ourselves, and is the wonder of strangers.

We have fifty seaports carrying on foreign trade. Our shipyards are full of life and our flag floats on every sea. All this is changed: we can regulate our own trade no longer. We must submit to the dictation of those who live above the tide, and who will know little of and care less for our interests or our experience.

The right of self-taxation, the power of the purse, is in every country the true security for freedom. We had it. It is gone, and the Canadians have been invested by this precious batch of worthies, who are now seeking your suffrages, with the right to strip us “by any and every mode or system of taxation.”

We struggled for years for the control of our Post Office. At that time rates were high, the system contracted; offices had only been established in the shire towns and in the more populous settlements. We gained the control, the rates were lowered and rendered uniform over the Provinces, newspapers were carried free, offices were established in all the thriving settlements and way offices on every road, but now all this comes to an end. Our Post Offices are to be regulated by a distant authority. Every post-master and every way office keeper is to be appointed and controlled by the Canadians.

Since the necessity for a better organization of the militia became apparent, our young men have shown a laudable spirit of emulation and have volunteered cheerfully, formed naval brigades, and shown a desire to acquire discipline and the use of arms. I have viewed these efforts with special interest. There is no period in the history of England when the great body of the people were better fed, better treated, or enjoyed more of the substantial comforts of life, than when every man was trained to the use of arms, and had his long-bow or his cross-bow in his house.

The rifle is the modern weapon, and our people have not been slow to learn the use of it. Organized by their own Government, commanded by their friends and neighbours, 50,000 men have been embodied and partially drilled for self-defence. But now strangers are to control this force—to appoint the officers and to direct its movements; and while our own shores may be undefended, the artillery company that trains upon the hills before us may be ordered away to any point of the Canadian frontier.

By the precious instrument by which we are hereafter to be bound, the Canadians are to fix the “salaries” of our principal public officers. We are to pay, but they can fix the amount, and who doubts but that our money will be squandered to reward the traitors who have betrayed us? Our “navigation and shipping” pass from our control, and the Canadians, who have not one ship to our three, are already boasting that they are the third maritime power in the world. Our “sea-coast and inland fisheries” are no longer ours. The shore fisheries have been handed over to the Yankees, and the Canadians can sell or lease tomorrow the fisheries of the Margaree, the Musquodoboit or the La Have.

Our “currency,” also, is to be regulated by the Canadians, and how they will regulate it we shrewdly suspect. Many of us remember when Nova Scotia was flooded with irresponsible paper, and have not forgotten the commercial crisis that ensued. In one summer thousands of people fled from the country, half the shops in Water Street, Halifax, were closed, and the grass almost grew in the Market Square. The paper was driven in. The banks were restricted to five-pound notes. All paper, under severe penalties, was made convertible. British coins were adopted as the standard of value, and silver has been ever since paid from hand to hand in all the smaller transactions of life.

For a quarter of a century we have had free trade in banking, and the soundest currency in the world. Last spring Mr. Galt could not meet the obligations of Canada, and he could only borrow money at ruinous rates of interest. He seized upon the circulation, and partially adopted the greenback system of the United States. The country is now flooded with paper; only, if I am rightly informed, convertible in two places—Toronto and Montreal. The system will soon be extended to Nova Scotia, and the country will presently be flooded with “shin-plasters,” and the sound specie currency we now use will be driven out.

Our “savings banks” are also to be handed over. Hitherto the confidence of the people in these banks has been universal. We had the security of our own Government, watched by our own vigilance, and controlled by our own votes, for the sacred care of deposits. What are we to have now? Nobody knows, but we do know that the savings of the poor and the industrious are to be handed over to the Canadians. They also are to regulate the interest of money. The usury laws have never been repealed in Nova Scotia, and yet capital could always be commanded here at six, and often at five per cent. In Canada the rate of interest ranges from eight to ten per cent, and is often much higher. With confederation will come these higher rates of interest, grinding the faces of the poor.

But it is said, why should we complain? we are still to manage our local affairs. I have shown you that self-government, in all that gives dignity and – security to a free state, is to be swept away. The Canadians are to appoint our governors, judges and senators. They are to “tax us by any and every mode” and spend the money. They are to regulate our trade, control our Post Offices, command the militia, fix the salaries, do what they like with our shipping and navigation, with our sea-coast and river fisheries, regulate the currency and the rate of interest, and seize upon our savings banks.

What remains? Listen, and be comforted. You are to have the privilege of “imposing direct taxation, within the Province, in order to the raising of revenue for Provincial purposes.” Why do you not go down on your knees and be thankful for this crowning mercy when fifty per cent has been added to your ad valorem duties, and the money has been all swept away to dig canals or fortify Montreal. You are to be kindly permitted to keep up your spirits and internal improvements by direct taxation.

Who does not remember, some years ago, when I proposed to pledge the public revenues of the Province to build our railroads, how Tupper went screaming all over the Province that we should be ruined by the expenditure, and that “direct taxation” would be the result. He threw me out of my seat in Cumberland by this and other unprincipled war-cries. Well, the roads have been built, and not only were we never compelled to resort to direct taxation, but so great has been the prosperity resulting from those public works that, with the lowest tariff in the world, we have trebled our revenue in ten years, and with a hundred and fifty miles of railroad completed, and nearly as much more under contract, we have had an overflowing treasury, and money enough to meet all our obligations, without having been compelled, like the Canadians, to borrow money at eight per cent, and to manufacture greenbacks.

But if we had been compelled to pay direct taxes for a few years to create a railroad system that by-and-by would be self-sustaining, and that would have been a great blessing in the meantime, the object would have been worth the sacrifice. But we never paid a farthing. What then? The falsehood did its work. Tupper won the seat, and now, after giving our railroads away, and all our general revenues besides, the doctor, after being rejected by Halifax, is trying to make the people of Cumberland believe that to pay “direct taxes” for all sorts of services is a pleasant and profitable pastime. Cumberland may believe and trust him again, but if it does, the people are not so shrewd or so patriotic as I think they are.

But listen, you have another great privilege. What do you think it is? You are allowed “to borrow money.” But will anybody lend it? Most people find that they can borrow money easiest when they do not want it, but where is it to be got? The general government, who can tax you “by any and every mode,” and override your legislation as they please, have also power to borrow. If I know anything of the men who now rule the roost in Canada, they will screw every dollar out of you that you are able to pay, and borrow while there is a pound to be raised at home or abroad. Thus fleeced, and with the credit of the Dominion thus exhausted, who will lend you a sixpence should you happen to want it? Nobody who is not a fool. There is not a delegate among the lot who would lend £100 upon such security.

But you have other great privileges. Listen again. You are generously permitted to maintain “the poor,” and to provide for your “hospitals, prisons and lunatic asylums.” We have it on divine authority that the poor “will be always with us,” and come what may we must provide for them. What I fear is that, under confederation, the number will be largely increased, and that when the country is taxed and drained of its circulation, the rich will be poorer and the industrious classes severely straitened. The lunatic asylum of course we must keep up, because Archibald may want it by-and-by to put Tupper and Henry into at the close of the elections.

Keep cool, my friends. This precious instrument confers upon you other high powers and privileges. You are permitted to establish local courts, and to “fine and imprison” each other. And this brings me to the key to this whole “mystery of iniquity.” Local courts you may establish. The Supreme Court is to be transferred to the general government, which is to appoint the judges and fix the salaries. Our judges now receive £700 or £800 currency per annum. The judges in Canada get £1000 or £1250 currency. The delegation which represented Nova Scotia in Canada and England was composed of five lawyers and a doctor. What the doctor is to get we may see by-and-by, but the five lawyers expect to be judges. John A. Macdonald knew this very well, and when he opened his confederation mouse-trap he did not bait it with toasted cheese. Judgeships, with these high salaries, was the bait that he dangled before their noses. They were caught, and though they hated each other, and had spoken a good deal of severe truth of each other before they went to Quebec, the bait produced a marvellous effect upon them, and, like a happy family, they have lived in brotherly love ever since, wagging their tails just whenever Mr. Macdonald told them.

But this bait was intended to have effect outside the mere delegation—to influence judges and lawyers in all the provinces. The confederates tell us that in this Province all the judges and lawyers are in favour of this scheme. If it were so, we should perhaps not be much surprised. All the carpenters would be in favour of it if you could convince them that their wages would be doubled. Let us hope that this assertion is but a scandal.

The bar, certainly, is not all in favour of the scheme. Many high-spirited men in the profession loathe the very name of confederation. As respects the judges, whatever may be their opinions, let us hope that they have never expressed them. Among the other inestimable blessings which we have had in Nova Scotia has been a pure administration of justice—a spotless ermine, worn by men above suspicion of political bias or corruption. Let us hope that this distinction may be ours while our old constitution lasts. “Shadows, clouds and darkness” rest upon the future, and nobody can tell what we are to have next.

Hitherto we have been a self-governed and independent community, our allegiance to the Queen, who rarely vetoed a law, being the only restraint upon our action. We appointed every officer but the Governor. How were the 1867 high powers exercised? Less than a century and a quarter ago, the moose and the bear roamed unmolested where we stand. Within that time the country has been cleared—society organized. The Province has been intersected with free roads—the streams have been bridged—the coasts lighted— the people educated, and all the modern facilities afforded by cheap postage, telegraphs, and railroads were rapidly being brought to every man’s door, and the growth of our mercantile marine evinced the enterprise and indomitable spirit of the people. A few years since there were eleven “captain cards” upon the Noel shore.

Some time ago I went into a house in the township of Yarmouth. There was a frame hanging over the mantelpiece with seven photographs in it. “Who are these?” I asked, and the matron replied, smiling, “These are my seven sailor boys.” “But these are not boys, they are stout powerful men, Mrs. Hatfield.” “Yes,” said the mother, with the faintest possible exhibition of maternal pride, “they all command fine ships, and have all been round Cape Horn.” It is thus that our country grew and throve while we governed it ourselves, and the spirit of adventure and of self-reliance was admirable. But now, “with bated breath and whispering humbleness,” we are told to acknowledge our masters, and, if we wish to ensure their favour, we must elect the very scamps by whom we have been betrayed and sold.

But we are told that we ought to be reconciled to all this because we are to have the Intercolonial Railroad, and because, financially, the delegates have made so good a bargain. If you will bear with me a few moments I will dissipate this delusion. I am speaking from memory, and my figures may not be strictly accurate. But in the main they will be found correct, and the argument based upon them is irresistible.

When I went into the Legislature in 1837 our revenue was about £60,000. It only doubled in seventeen years, before we commenced building our railroads. In 1854 we passed our railroad laws, and in 1855 Tupper went screaming all over Cumberland, prophesying ruin and decay. In ten years since then our revenues have trebled, and last year amounted to £400,000. We have built the road to Truro, the road to Windsor, the extension to Pictou; and before this precious bargain and sale of all our resources was consummated we had the Northern road to New Brunswick, all of the Intercolonial within our borders, and the road to Annapolis under contract.

We had money enough to pay for all these roads without being under any compliment to the Canadians or the British Government either; and in ten years more, without financial embarrassment, could have extended our system to Yarmouth on the one side, and to Sydney on the other. At this moment it was—with my railroad policy so successful—the country, that Tupper swore I had ruined, so prosperous—the treasury, which he declared was milked dry, overflowing year by year, under the tariff we bequeathed to him, and our debentures two or three per cent above the bonds of Canada—that we were sold like sheep. This was the moment for these delegates to step in and trade us away, our rights and revenues, to Canada. God help us, and enable us “to possess our souls in patience.” No such deed as this was ever done or attempted where death was not the penalty.

I cannot help smiling when I hear Tupper crowing about the railroads he has built. He ought to be ashamed of vain boasting. We all know, and he knows, that had his warning voice been heeded, there never would have been a mile of railroad built in Nova Scotia up to this hour. The roads to Windsor and to Truro were built upon the policy inaugurated by myself, and with the money borrowed by me in England. What had he to do with it? Just this— that the Government having changed, he and his colleagues paid away about £40,000 of your money to a parcel of contractors who set up irregular claims. All the roads made since have been made on my policy of pledging the public credit to make them, which Tupper declared would be ruinous. There has been, however, an important difference in the mode of dealing with contracts and expending the money, which ought to be held up to indignant reprobation.

When I was at the head of the Railway Board I was surrounded by six business men, an accountant, and an engineer. Every mile of road was thrown open to competition by tender and contract. When tenders were sent in they were placed in custody of the accountant till the time expired, and the whole board assembled. I never looked at one of them till they were opened in presence of all the commissioners, the accountant, and engineer. The lowest tender, if the party produced good security, took the contract, without reference to politics, to country, or to creed. Look at the new system inaugurated by Dr. Tupper. Take the Pictou line as an illustration. A number of our own people tendered for the work. If kindly treated, some of them might have pulled through. If they did not, their bondsmen were liable. By a system of dealing, instead of the work being put up to tender again, the whole was handed over to the engineer by private bargain, a system most unfair to the whole people, and open to suspicion of gross favouritism and corruption. Instead of offering the northern and western lines to fair competition, the Government took powers to hand them over, by private bargain, to whomever they chose to select. I do not say, because I cannot prove, that any of the members of the Government were sleeping partners, or profited by these contracts. But I do say that the system was most perilous to the public interests, and open to grave objections. We pray to be “kept out of temptation,” but these gentlemen, with profitable contracts to dispose of, amounting to nearly a million and a half of money, exposed themselves to temptations hard to resist, and laid themselves open to suspicions widely entertained. I left the Railway Board as poor as I went into it. I bought or built no property then or since. I hope those who succeeded to the administration have left with hands as clean.

Let me turn your attention, now, to the bargain that has been made with Canada. We give them the roads already completed, which have cost nearly a million and a half. We give them the roads under contract, which may cost another million. We give them revenue enough to cover the interest upon these roads, till they pay, when they will get them for nothing, and have the revenue besides. Our whole revenue now amounts to £400,000. It has trebled in ten years. If it only doubles in the next ten we will have £800,000. By that time our old roads will pay, and the new ones yield half the interest. Out of this sum we are to get back of our own money £133,000, a sum utterly inadequate to provide for Provincial services now, and by that time deplorably insufficient. We can only provide for those services by direct taxation. The Canadians get all the rest.

Hitherto I have reasoned upon a ten per cent. tariff, which would have provided for all our wants, and given a fund for railway extension to the extremities of the Province, east and west. But we know that under confederation our tariff will be raised to fifteen per cent. If the revenue is collected, taking our Customs duties at $1,231,902, the additional taxation will take out of our pockets $500,000 the very first year. The interest on the £3,000,000 required for the Intercolonial road is £120,000 sterling. The road will take four years to construct. The Canadians will only pay interest as the work goes on, yet from the start they will take out of our pockets by increased duties, to say nothing of the general revenues surrendered, £100,000 sterling, a sum nearly sufficient to pay the interest on the whole three millions. This is the profitable bargain they have made, and they have the audacity to suppose that Nova Scotians are such idiots that they can cover up the transaction with every species of falsehood and mystification. They shall not do this. It shall be presented to the people everywhere in its naked deformity and injustice, and when it is they will pronounce universal condemnation. You have been told that Mr. Annand, Mr. McDonald, and I opposed the Intercolonial Railroad. Why, if the bargain had been a good one, we would have flung the road to the winds to save the independence of the Province, but being what it is, a fraud upon the revenues and an insult to the common sense of Nova Scotia, we did our best to defeat it.

But confederation will bring with it other blessings. Stamp duties, hitherto unknown, will soon be imposed, and toll-bars will become ornaments of the scenery. We have but two toll bridges in the Province, and all our roads are free. In Canada you can hardly travel five miles without being stopped by a toll-bar, and compelled to pay for the use of the road. Our newspapers now go free, but they will soon be taxed as they are in Canada. For all these mercies should we not be thankful to the delegates? Yes, as thankful as men are for the plague or the smallpox.

But we are told when we complain of this fraudulent conveyance of our independence—of this reckless sacrifice of our dearest interests, that we are disloyal—that we are annexationists, Fenians, and dangerous persons. Are we indeed?

A year ago there was no annexationist in Nova Scotia. If there are any now, we have to thank those who have overthrown our institutions, and treated the population with contempt. This old cry of disloyalty does not terrify me. It has been raised by some interested faction at every crisis of our Provincial history. I met it at the outset of my public life, and trampled the accusation under my feet in the old trial with the magistrates of Halifax. I met it again at the outbreak of the Canadian rebellion, and put the enemy to shame by the publication of my letter to Chapman. The records are here, and he who runs may read.

[Holding up a volume of speeches.] Surrounded by the élite of Massachusetts, all the Yankees eminent in station and distinguished by talent, I have vindicated the institutions and upheld the honour of Great Britain. You know—these wretched slanderers know—how at Detroit, before the commercial representatives of the Provinces and of the Northern States, I won the respect of our neighbours by the triumphant vindication of British interests; and won what, perhaps, I valued as much, the thanks of my Sovereign, conveyed to me by the Secretary of State. But Dr. Tupper accuses me of disloyalty, does he, and sets his newspapers, subsidized with public plunder, to asperse better men than himself?

Let me contrast his conduct with my own. During the Crimean war our army was decimated by the great battles of the Alma, Balaclava and Inkerman. Surrounded by hordes of Russians, and suffering for supplies, there was some risk that they might be driven into the sea. Reinforcements were urgently required, and a Foreign Enlistment Act was passed. To assist in carrying out that Act I risked my life for two months in the United States, surrounded by Russian agents, American sympathisers, and Fenians. Mr. Gibson, now in this room, was in New York at the time, and knew the state of feeling, and urged me to quit the service and not risk imprisonment or personal violence. I persevered, rarely sleeping twice in the same bed till recalled; and this I did for England in her hour of peril, and never received a pound for my services, or asked one.”

Now, what was Dr. Tupper doing at this time? He was scouring the county of Cumberland while I was absent on the service of the Crown, meanly endeavouring to deprive me of my seat. He slandered me in every part of the county—he invented stories that I was imprisoned and would not be back. I only got back a few days before the election, too late for any canvass or efficient organization, and was defeated, of course. In this dishonourable mode he won the seat he now holds, and certainly illustrated his devotion to his Sovereign after a mode that ought to be remembered. At a later period, in 1862, when, foreseeing the dangers which have since threatened these Provinces, my Government revived the militia law and increased the annual grant for defence, did not this very loyal gentleman endeavour to reduce the Governor’s salary, to deprive him of the vote for a secretary, and to strike out $8000 of the grant for the militia upon the ground that the Province was so poor that it could not afford the expense?

I pass by this “retrenchment scheme” as utterly beneath contempt. I pass by the wretched jobs by which his administration has been distinguished – from its commencement to its close. Let me waste a few words on the cry that “we ought to send the best men”—by which, of course, these precious delegates mean themselves. The best men of this lot, bad is the best. Now the best men to send are not scheming lawyers, who would dig up and sell their fathers’ bones for money or preferment, but honest men in whom the people of this country have entire confidence. Dr. Tupper has already chosen his twelve senators, and now he wants to be allowed to choose the people’s representatives. Why should he not? You were too stupid to pass an opinion upon confederation. Are you sure that you have sense enough to choose a representative?

The “best men”!—let us see how he has chosen. In the first place he has taken six senators from one county, leaving eleven counties entirely unrepresented. Then he has taken three men who were open and avowed anti-confederates; who ratted, sold themselves, and were purchased by the distinction. A friend came in and told me last spring that he was afraid Bill was being tampered with, as he saw Tupper taking him up to Government House that morning. I discredited the story, because I did not believe that the Queen’s representative would degrade his office by canvassing and tampering with members of the House. I think so still. No doubt the visit was one of mere form, but Caleb’s name appears in the list of Ottawa senators, and who doubts how his sudden conversion was effected? Compare him with McHeffy, who is in gentlemanly manners, intelligence and sturdy independence, out of sight his superior. Yet the best man is left behind because he would not sell his country. Who does not remember Miller denouncing the confederation scheme on the platform in Temperance Hall, and there and everywhere declaring that it ought to be sent to the hustings. But he was a convert, and the price must be paid, even though Mather Almon, who in experience and weight of character was his superior in every quality required for a legislator, should be left behind.

Of the candidates who have presented themselves for the representation of this county on the other side, it is enough to say that they are on that side, and are not the men for Galway. I would vote against my own brother if he had a hand in these transactions, or if he attempted to justify the mode in which the people of Nova Scotia have been treated. The very life and soul of any country are honour and good faith. We can never hold up our heads till we stamp out treachery, as we would the rinderpest if it came here. We would not let a plague spread among our cattle, and we must not allow our people to be contaminated with the example of these delegates. Such treason as theirs, in other countries, would earn for them the halter or axe. We may not even elevate them to the dignity of tar and feathers, but we can at least leave them on the stools of repentance to become wiser and better men.

Of the people’s candidates I need say but little. They are known to you all, as industrious, honest, business men, of shrewdness and intelligence. Mr. Cochrane and Mr. Power are universally respected by the body to which they belong, and enjoy the confidence of the community. Mr. Jones and Mr. Northup are men to whom you can safely entrust your interests at home and abroad. Mr. Balcom I have known for twenty years. I have slept beneath his roof, and know that in his domestic relations and in his commercial activity he is a fitting representative of the sturdy class of men who are enlivening the sea-coast by their industry. None of these men care for public distinctions. They would retire tomorrow, if by so doing they could serve their country. They can serve her best by fighting her battles out, and I hope to see the whole five triumphantly returned.

Howe, Joseph. Annand, William. Chisholm, Joseph Andrew. “The Speeches and Public Letters of Joseph Howe” Halifax, Canada: The Chronicle publishing company, 1909. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007688708

The story of Christ Church, Dartmouth

- When Halifax was first settled, this side of the harbor was the home and hunting ground of the [Mi’kmaq].

- Soon after the settlement of Halifax, Major Gillman built a saw mill in Dartmouth Cove on the stream flowing from the Dartmouth lakes.

- On September 30th 1749, [Mi’kmaq] attacked and killed four and captured one out of six unarmed men who were cutting wood near Gillman’s mill.

- In August 1750, the Alderney, of 504 tons, arrived at Halifax with 353 immigrants, a town was laid out on the eastern side of the harbor in the autumn, given the name of Dartmouth, and granted as the home of these new settlers.

- A guard house and military fort was established at what is still known as Blockhouse hill [—the hill on King Street, at North].

- In 1751 [Mi’kmaq] made a night attack on Dartmouth, surprising the inhabitants, scalping a number of the settlers and carrying off others as prisoners.

- In July 1751, some German emigrants were employed in picketing the back of the town as a protection against the [Mi’kmaq].

- In 1752, the first ferry was established, John Connor, of Dartmouth, being given the exclusive right for three years of carrying passengers between the two towns.

- Fort Clarence was built in 1754.

- In 1758 the first Charles Morris, the Surveyor General, made a return to Governor Lawrence giving a list of the lots in the town of Dartmouth.

- In 1762 the same Charles Morris wrote: “The Town of Dartmouth, situate on the opposite side of the harbour, has at present two families residing there, who subsist by cutting wood.”

- In 1785 three brigantines and one schooner with their crews and everything necessary for the whale fishery arrived, and twenty families from Nantucket were, on the invitation of Governor Parr, settled in Dartmouth. These whalers from Nantucket were Quakers in religion. Their fishing was principally in the Gulf of St. Lawrence which then abounded with black whales.

- In 1788 a common of 150 acres [—200 acres, in keeping with with the New England tradition of “200 acres for a common, sixty acres for a Town Site“, (1808 Toler map overlay) and certain tracts for a meeting house, cemetery, school”] was granted Thomas Cochran, Timothy Folger and Samuel Starbuck in trust for the town of Dartmouth. When these good Quakers left, Michael Wallace, Lawrence Hartshorne, Jonathon Tremaine, all subsequently members of Christ Church, were made trustees [in 1798]. Acts relating to this common were passed in 1841, 1868 and 1872, and the present Dartmouth Park Commission was appointed in 1888.

- In 1791 the idea of building a canal between the Shubenacadie river and Dartmouth by utilizing the lakes, a plan which originated with Sir John Wentworth, was brought before the legislature. The Shubenacadie Canal company was incorporated in 1826.

- In 1792 most of the Quakers left Dartmouth. One at least, Seth Coleman, ancestor of the Colemans of today, remained.

- In early days Lawrence Hartshorne, Johnathon Tremain and William Wilson all Churchmen, carried on grist-mills at Dartmouth Cove. At a ball given by Governor Wentworth on December 20th, 1792, one of the ornaments on the supper table was a reproduction of Messrs. Hartshorne and Tremain’s new flour mill.

- Many French prisoners of war were brought here off the prizes brought to the port of Halifax. Some were confined in a building near the cove, which now forms part of one of the Mott factories.

- In 1797 “Skipper” John Skerry began running a public ferry between Halifax and Dartmouth.

- In 1809 Dartmouth contained 19 houses, a tannery, a bakery and a grist-mill.

- In 1814 Murdoch relates that “Sir John Wentworth induced Mr. Seth Coleman to vaccinate the poor persons in Dartmouth, and throughout the township of Preston adjoining. He treated over 400 cases with great success.”

- The team boat Sherbrooke made her first trip across the harbor on November 8th, 1816.

- As already related the first schools in the town were established by the Church of England, the teachers getting salaries, small it is true, from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Mary Munn (appointed 1821) was the first teacher of the girls at a salary of £5 a year. William Walker (appointed 1824), father of E.M. Walker, and grandfather of H.R. Walker, now superintendent of Christ Church Sunday School, at £15 year of the boys. Mr. Walker held school in a little half stone house on the site of the present Central School. The S.P.G. was specially anxious for the religion instruction of the children, and the following “Prayers for the use of the Charity Schools in America”, issued by the society were doubtless regularly used by these early teachers.

- A fire engine company was formed in 1822, a Axe and Ladder Company in 1865, and a Union Protection Company in 1876.

- Lyle & Chapel opened a shipyard about 1823.

- In 1828 a steam ferry boat of 30 tons, the Sir Charles Ogle, was built at the shipyard of Alexander Lyle. In 1832 a second steamer, the Boxer, was built; and in 1844 a third, the Micmac.

- In 1836 the ice business was commenced. William Foster erecting an ice house near the Canal Bridge on Portland Street. The ice was taken in a wheel-barrow to Mr. Foster’s shop in Bedford Row, Halifax, and sold for a penny a pound.

- In the thirties the industries of Dartmouth included besides the grist mill, of which William Wilson was chief miller, a foundry run by James Gregg on the hill back of the railway station; the manufacture of putty and oils by William Stairs; a tannery kept by Robert Stanford; a tobacco factory; the making of silk hats or “beavers” by Robinson Bros.; a soap chandlery run by Benjamin Elliott opposite Central School, and several ship building plants.

- It is estimated that altogether $359,951.98 was spent on this canal. The stone locks and parts of the canal are all that remain today.

- Edward H. Lowe, a leading member of Christ Church, was for many years secretary and manager of the Dartmouth Steamboat Company. At his death he was succeeded by another good Churchman, Captain George Mackenzie, whose wife was a daughter of Rev. James Stewart.

- The first vessel built in Dartmouth was called the “Maid of the Mill”, and was used in carrying flour from the mill then in full operation.

- In 1843 Adam Laidlaw, well known as driver of the stage coach between Windsor and Halifax, commenced cutting and storing the ice on a large scale, making this his only business.

- In 1845 a Mechanics Institute, the first of the kind in Nova Scotia, was formed in Dartmouth.

- The first regatta ever held on Dartmouth Lake is said to have been that on October 5th, 1846.

- About 1853 the late John P. Mott commenced his chocolate, spice and soap works.

- In 1853 the inland Navigation company took over the property and in 1861 a steam vessel of 60 tons, the Avery, went by way of the canal to Maitland and returned to Halifax.

- In 1856 George Gordon Dustan Esq., purchased “Woodside.” He was much interested in the refining of sugar, and the Halifax Sugar Refinery company was organized with head offices in England, and Mr. Dustan was one of the directions. The first refinery was begun in 1883, and sugar produced in 1884. In 1893 the refinery was transferred to the Acadia Sugar Refinery Company, then just founded.

- Mount Hope, the Hospital for the insane, was erected between 1856 and 1858, the first physician being in charge being Dr. James R. DeWolfe.

- About 1860 the Chebucto Marine Railway Company was found by Albert Pilsbury, American Consul at Halifax, who then resided at “Woodside,” four large ships being built by H. Crandall, civil engineer.

- In 1860 the Dartmouth rifles were organized with David Falconer as captain, and J.W. Johnstone (afterwards Judge) and Joseph Austen as lieutenants.

- A month later the Dartmouth Engineers with Richard Hartshorne as captain and Thomas A. Hyde and Thomas Synott lieutenants were found.

- Gold was discovered at Waverly in 1861.

- In 1862 the whole property and works were sold by the sheriff to a company which was styled “The Lake & River Navigation Company,” which worked the canal for a little time at a small profit. Thousands of pounds were spent on the enterprise.

- The works of the Starr Manufacturing Company were commenced by John Starr in 1864, associated with John Forbes. At first they made iron nails as their staple products. Mr. Forbes invented a new skate, the Acme, which gained a world-wide reputation, and in 1868 a joint company was formed.

- In 1869 the Boxer was sold and the old Checbucto also built there, put in her place.

- In 1868 the firm of Stairs, Son & Morrow decided to commence the manufacture of rope, selected Dartmouth for the site of the industry, erected the necessary buildings and apparatus in the north end of the town, and began the manufacture of cordage in 1869.

- Dartmouth was incorporated by an act of the Provincial Assembly in 1873 with a warden and six councillors. The first warden was W.S. Symonds, the first councillors, Ward 1 J.W. Johnstone, Joseph W. Allen; Ward 2, John Forbes, William F. Murray; Ward 3, Thomas A. Hyde, Francis Mumford.

- In 1885 a railway was constructed from Richmond to Woodside Sugar Refinery, with a bridge across the Narrows 650 feet long, which was swept away during a terrific wind and rain storm on Sept. 7th, 1891. A second bridge at the same place was carried away on July 23rd, 1893.

- In 1886 the railway station was built.

- In 1888 the Dartmouth (ferry) was built.

- The present Ferry Commission was appointed on April 17th 1890. It purchased the Arcadia from the citizens committee, and also the Annex 2 of the Brooklyn Annex Line, which was renamed the Halifax. The Steam Ferry Company finally sold out to the Commission, thus terminating an exciting contest between town and company.

- In 1890 the Halifax and Dartmouth Steam Ferry Company withdrew the commutation rates, and the indignant citizens purchased the Arcadia which carried foot passengers across for a cent, but at a loss.

- Until 1890 most of the water was obtained from public wells and pumps.

- In 1891 a Water Commission was formed. E.E. Dodwell, C.E. was appointed engineer, and on November 2nd 1892, our splendid water supply was turned on for the first time.

- In 1891 a public reading room, believed “to be the only free reading room in the province” at the time, was established near the ferry docks.

- The old brick post office near the ferry was erected in 1891, the present fine building quite recently.

- On July 13th 1892, the Dartmouth Electric Light and Power Company began its service.

- Woodside once had a brickyard and lime kilns, first owned by the late Samuel Prescott. They then passed by purchase to Henry Yeomans Mott, father of John Prescott Mott and Thomas Mott.

- Mount Amelia was built by the late Judge James William Johnstone.

- Among the early settlers in Dartmouth was Nathaniel Russell, an American loyalist, who settled near the Cole Harbor Road near Russell Lake. He was the father of Nathaniel Russell, who took so great an interest in the Mechanics Institute, grandfather of Mr. Justice Benjamin Russell, great grandfather of H.A. Russell, one of our progressive citizens of today.

- The Rev. J.H.D. Browne, now of Santa Monica, California, and editor of the Los Angeles Churchman, who was with the Late Archdeacon Pentreath, one of the founders of Church Work, was born and spent his boyhood in Dartmouth.

- Captain Ben Tufts was the first settler at Tuft’s Cove.

- John Gaston, who lived near Maynard’s Lake, drove a horse and milk wagon into Halifax, a two-wheeled conveyance known as “Perpetual Motion”. He is said to have been the first to extend his milk route from this side to Halifax.

See also:

Vernon, C. W. "The story of Christ Church, Dartmouth" [Halifax, N.S.] : publisher not identified , 1917 https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.80672

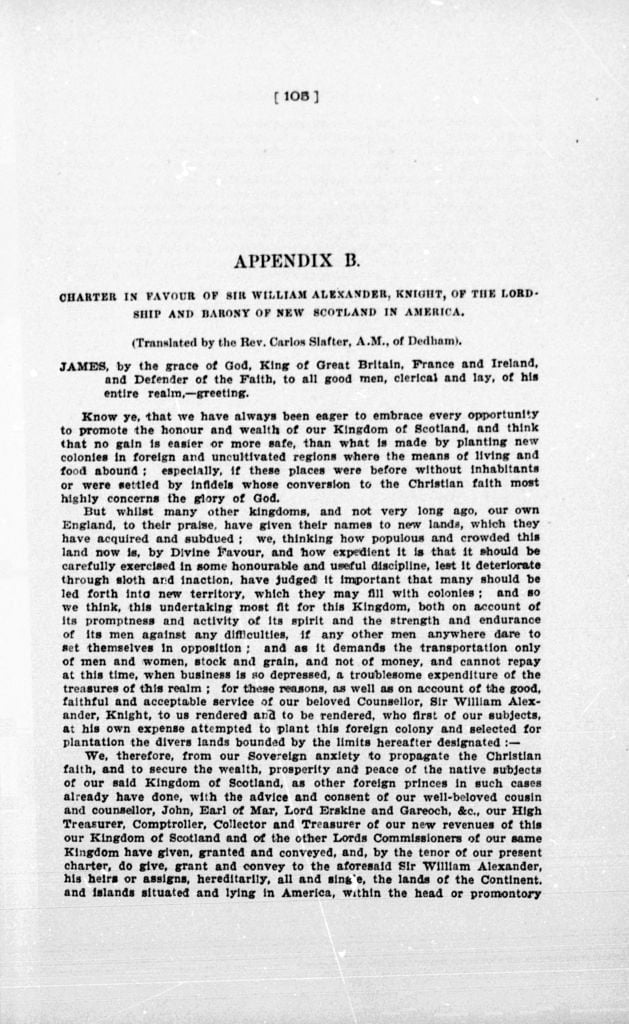

Charter In Favor Of Sir William Alexander, Knight, Of The Lordship And Barony Of New Scotland In America

(See also: https://cityofdartmouth.ca/nova-scotias-charter/)

(Translated by the Rev, Carlos Slafter, A.M., of Dedham).

JAMES, by the grace of God, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, ‘and Defender of the Faith, to all good men, clerical and lay, of his entire realm,—greeting.

Know ye, that we have always been eager to embrace every opportunity to promote the honour and wealth of our Kingdom of Scotland, and think that no gain is easier or more safe, than what 1s made by planting new colonies in foreign and uncultivated regions where the means of living and food abound; especially, if these places were before without inhabitants or were settled by infidels whose conversion to the Christian faith most highly concerns the glory of God.

But whilst many other Kingdoms, and not very long ago, our own England, to their praise, have given their names to new lands, which they have acquired and subdued ; we, thinking how populous and crowded this land now is, by Divine Favour, and how expedient it is that it should be carefully exercised in some honourable and useful discipline, lest it deteriorate through sloth and inaction, have judged it Important that many should led forth into new territory, which they may fill with colonies; and so we think, this undertaking most fit for this Kingdom, both on account of its promptness and activity of its spirit and the strength and endurance of its men against any difficulties, if any other men anywhere dare to set themselves In opposition; and as it demands the transportation only of men and women, stock and grain, and not of money, and cannot repay at this time, when business is so depressed, a troublesome expenditure of the treasures of this realm; for these reasons, as well as on account of the good, faithful and acceptable service of our beloved Counsellor, Sir William Alexander, Knight, to us rendered ara to be rendered, who first of our subjects, at his own expense attempted to plant this foreign colony and selected for plantation the divers Iands bounded by the limits hereafter designated :—

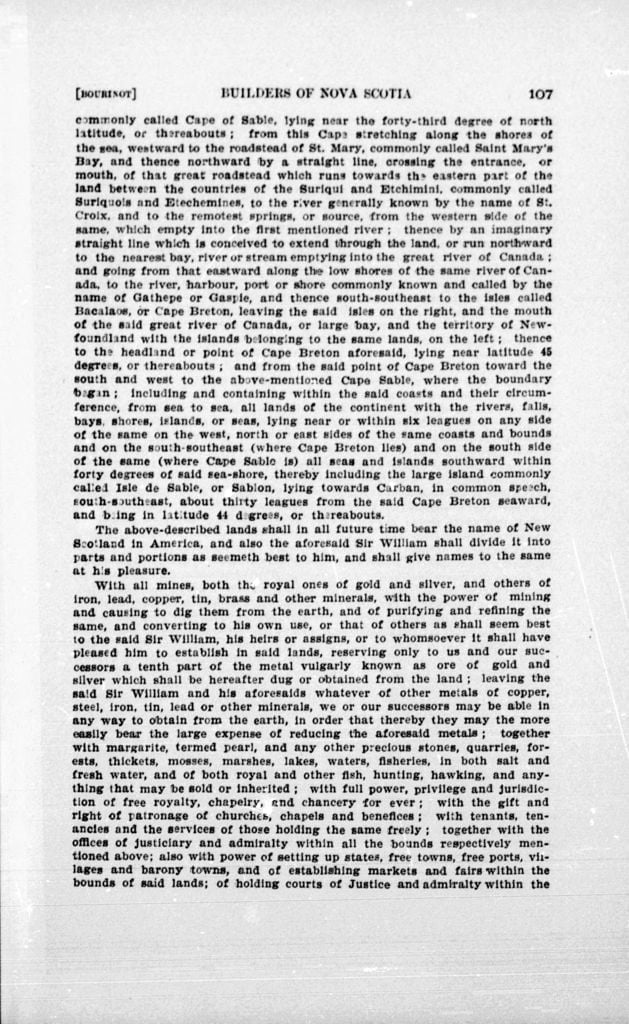

‘We, therefore, from our Sovereign anxiety to propagate the Christian faith, and to secure the wealth, prosperity and peace of the native subjects of our said Kingdom of Scotland, as other foreign princes in such case already have done, with the advice and consent of our well-beloved co and counsellor, John, Earl of Mar, Lord Brakine and Gareoch, &., our High Treasurer, Comptroller, Collector and Treasurer of our new revenues of this ‘our Kingdom of Scotland and of the other Lords Commissioners of our same Kingdom have given, granted and conveyed, and, by the tenor of our present charter, do give, grant and convey to the aforesaid Sir William Alexander, his heirs or assigns, hereditarily, all and single, the lands of the Continent, and islands situated and lying in America, within the head or promontory commonly called Cape of Sable, tying near the forty-third degree of north latitude, or thereabouts; from this Cape stretching along the shores of the sea, westward to the roadstead of St. Mary, commonly called Saint Mary’s Bay, and thence northward by a straight line, crossing the entrance, of mouth, of that great roadstead which runs towards the eastern part of the the countries of the Suriqui and Etchimini, commonly called Suriquois and Etchemines, to the river generally known by the name of St. Croix, and to the remotest springs, or source, from the western side of the same, which empty Into the first mentioned river ; thence by an imaginary straight line which is conceived to extend through the land, or run northward to the nearest bay, river or stream emptying Into the great river of Canada; ‘and going from that eastward along the low shores of the same river of Canada, to the river, harbour, port or shore commonly known and called by the name of Gathepe or Gaspie, and thence south-southeast to the isles called Bacalaoe, or Cape Breton, leaving the said isles on the right, and the mouth of the said great river of Canada, or large bay, and the territory of Newfoundland with the islands belonging to the same lands, on the left; thence to the headland or point of Cape Breton aforesaid, lying near latitude 45 degrees, or thereabouts; and from the said point of Cape Breton toward the south and west to the above-mentioned Cape Sable, where the boundary an; including and containing within the said coasts and their circumference, from sea to sea, all lands of the continent with the rivers, fall bays, shores, islands, or lying near or within six leagues on any side of the same on the west, north or east sides of the same coasts and bounds and on the south-southeast (where Cape Breton lies) and on the south side of the same (where Cape Sable is) all seas and islands southward within forty degrees of said seashore, thereby including the large island commonly called Isle de Sable, or Sablon, lying towards Carban, in common speech, south-southeast, about thirty leagues from the said Cape Breton seaward, and being in latitude 44 degrees, or thereabouts.

The above-described lands shall in all future time bear the name of New Scotland in America, and also the aforesaid Sir William shall divide it into parts and portions as seemeth best to him, and shall give names to the same at his pleasure.

‘With all mines, both the royal ones of gold and silver, and others of tron, lead, copper, tin, brass and other minerals, with the power of mining ‘and causing to dig them from the earth, and of purifying and refining the same, and converting to his own use, or that of others as shall seem best to the said Sir William, his heirs or assigns, or to whomsoever it shall have pleased him to establish in said lands, reserving only to us and our successors a tenth part of the met silver which shall be hereafter dug or obtained from the land said Sir William and his aforesaids whatever of other metals of copper, steel, iron, tin, lead or other minerals, we or our successors may be able in any way to obtain from the earth, in order that thereby they may the more easily bear the large expense of reducing the aforesaid metals; together with margarite, termed pearl, and any other precious stones, quarries, forests, thickets, mosses, marshes, lakes, waters, fisheries, in both salt and fresh water, and of both royal and other fish, hunting, hawking, and anything that may be sold or inherited; with full power, privilege and jurisdiction of free royalty, chapelry, end chancery for ever; with the gift and right of patronage of churches, chapels and benefices; with tenants, tenancies and the services of those holding the same freely; together with the offices of justiciary and admiralty within all the bounds respectively mentioned above; also with power of setting up states, free towns, free ports, villages and barony towns, and of establishing markets and fairs within the bounds of said lands; of holding courts of Justice and admiralty within the limits of such lands, rivers, ports and seas; also with the power of Improving, levying and receiving all tolls, customs, anchor-dues and other of the said towns, marts, fairs and the free ports; and of owning and using the same as freely in all respects as any greater or lesser Baron in our Kingdom of Scotland has enjoyed in any past, or could enjoy in any future time; with all other prerogatives, privileges, Immunities, dignities, perquisites, profits, and dues concerning and belonging to said lands, seas, and the boundaries thereof, which we ourselves can give and grant, as freely and in as ample form as we or any of our noble ancestors granted any charters, letters patent, enfeoffments, gifts, or commissions to any subjects of whatever rank or character, or to any society or company leading out Such colonies into any foreign parts, or searching out foreign land in free and ample form as if the same were included in this present charter ; also we make, constitute and ordain the said Sir William Alexander, his heirs and assigns, or their deputies, our hereditary Lieutenants-General, for representing our royal person, both by sea and by land, in the regions of the sea, and on the coasts, and in the bounds aforesaid, both in seeking said lands and remaining there and returning from the same; to govern, rule, punish and acquit all our subjects who may chance to visit or inhabit the same, or who shall do business with the same, or shall tarry in the said places ; also, to pardon the same, and to establish such laws, statutes, constitutions, orders, instructions, forms of governing and ceremonies of magistrates in said bounds, as shall seem fit to Sir William Alexander himself, of his aforesaids, for the government of the said region, or of the inhabitants of the same, in all causes, both criminal and civil; also, of changing and altering the said laws, rules, forms and ceremonies, as often as he or his aforesaids shall please for the good and convenience of said region ; so that said laws may be as consistent as possible with those of our realm of Scotland, We also will that, in case of rebellion or sedition, he may use martial law against delinquents or such as withdraw themselves from his power, freely as any lieutenant whatever of our realm or dominion, by virtue of the office of lieutenant, has, or can have, the power to use, by excluding all other officers of this our Scottish realm, on land or sea, who hereafter can pretend to any claim, property, authority or interest in or to said lands or province aforesaid, or any jurisdiction therein by virtue of any prior disposal of patents; and, that a motive may be offered to noblemen for joining this expedition and planting a colony in said lands, we, for ourselves and our heirs and successors, with the advice and consent aforesaid, by virtue of our Present charter, do give and grant free and full power to the aforesaid Sir ‘William Alexander and his aforesaids, to confer favours, privileges, gifts and honours to those who deserve them, with full power to the same, or any one of them, who may have made bargains or contracts with Sir William, or hie deputies for the said lands, under his signature, or that of his deputies, and under the seal hereinafter described, to dispose of and convey any part or parcel of said lands, ports, harbours, rivers or of any part of the premises: ‘also, of erecting machines of all sorts, introducing arts or sciences or practicing the same, in whole or in part, as he shall judge to be to their advantage; also, to give, grant and bestow such offices, titles, rights and powers, make and appoint such captains, officers, bailiffs, governors, clerks and all other officers, clerks and ministers of royalty, barony and town, for the execution of justice within the bounds of said lands, or on the way to these lands by sea, and returning from the same, as shall seem necessary to him, according to the qualities, conditions and deserts of the persons who may happen to ‘dwell in any of the colonies of said province, or in any part of the same, or ‘who may risk their goods and fortunes for the advantages and increase of the ‘same ; also, of removing the same persons from office, transferring or chan; ing them, as far as it shall seem expedient to him and his aforesaide.

And, since attempts of this kind are not made without great labour and expense, and demand a large outlay of money, so that they exceed the means of any private man, and on this account the said Sir William Alexander and his aforesaids may need supplies of many kinds, with many of our subjects and other men for special enterprises and ventures therein, who may form contracts with him, his heirs, assigns or deputies for lands, fisheries, trade, or the transportation of people and their flocks, goods and effects to the said New Scotland, we will that whoever shall make such contracts with the said Sir William and his aforesaids under their names and seals, by limiting, assigning and fixing the day and place for the delivery of persons, goods and effects on shipboard, under forfeiture of a certain sum of money, and shall not perform the same contracts, but shall thwart and injure him in the proposed voyage, which thing will not only oppose and harm the said Sir ‘William and his aforesaids, but also prejudice and damage our so laudable intention; then it shall be lawful to the said Sir William and his aforesaids, or their deputies and conservators hereinafter mentioned, in such case to velze for himself, or his deputies whom he may appoint for this purpose, all such sums of money, goods and effects forfeited by the violation of these contracts. And that this may be more easily done, and the delay of the law be avoided, we have given and granted, and by the tenor of these presents ¢o give and grant full power to the Lords of our Council, that they may reduce to order and punish the violators of such contracts and agreements made for the transportation of persons. And although all such contracts ‘between the said Sir William and his aforesaids and the aforesaid adventurers shall be carried out in the risk and the conveyance of people with their goods and effects, at the set time; and they with all their cattle and goods arrive at the shore of that province with the intention of colonizing and abiding there; and yet, afterwards, shall leave the province of New Scotland altogether, and the confines of the same, without the consent of the said Sir Wlliam and his aforesaids or their deputies, or the society and colony afovesaid, where first they had been collected and joined together; and shall go away to the uncivilized natives, to live In remote and desert places; then they shall lose and forfeit all the lands previously granted them; also all their goods within the aforesaid bounds; and it shall be lawful for the said Sir William and his aforesalds to confiscate the same, and to reclaim the same lands, and to seize and convert and apply to his own use and that of his aforesaids all the same b longing to them, or any one of them.

And that all our beloved subjects, as well of our kingdoms and dominions, so also others of foreign birth who may sail to the said lands, or any part of the same, for obtaining merchandise, may the better know and obey the power and authority given by us to the aforesaid Sir William Alexander, our faithful counsellor, and his deputies, in all ‘such commissions, warrant: and contracts as he shall at any time make, grant and establish for the more fit and safe arrangement of offices, to govern said colony, grant lands and execute justice In respect to the said inhabitants, adventurers, deputies, factors or assigns, in any part of said lands, or in failing to the same, we, with the advice and consent aforesaid, do order that the said Sir William Alexander and his aforesaids shall have one common seal, pertaining to the office of Lieutenant of Justiciary and Admiralty, which by the said Sir ‘William Alexander and his aforesalds or their deputies, in all time to come, shall be safely kept; on one side of it our arms shall be engraved, with these words on the circle and margin thereof :—”Sigillur: Regis Scoliae Angliae Franclae et Hybernlae,” and on the other side our image, or that of our successors, with these words :—” Pro Novae Scotiae Locum Tenente,” ‘and a true copy of it shall be kept in the hands and care of the conservator of the privileges of New Scotland, and this he may use in his office as occasion shall require. And as it is very important that all our beloved subjects who inhabit the said province of New Scotland or its borders may live in the fear of Almighty God and at the same time in his true worship, ‘and may have an earnest purpose to establish the Christian religion therein, ‘and also to cultivate peace and quiet with the native inhabitants and savage aborigines of these lands, so that they, and any others trading there, may safely, pleasantly and quietly hold what they have got with great labour and peril, we, for ourselves and successors, do will and decree, and by our present charter give and grant to the said Sir William Alexander and his aforesaids and their deputies, or any other of our government officers and ministers whom they shall appoint, free and absolute power of arranging and securing peace, alliance, friendship, mutual conferences, assistance and Intercourse with those savage aborigines and their chiefs, and any others bearing rule and power among them; and of preserving and fostering such relations and treaties as they or their aforesaids shall form with them; provided those treaties are, on the other side, kept faithfully by these barbarians; and, unless this be done, of taking up arms against them, whereby they may be reduced to order, as shall seem fitting to the said Sir William and his aforesaids and deputies, for the honour, obedience and service of God, and the stability, defence and preservation of our authority among them; which power also to the said Sir William Alexander and his aforesaids, by themselves or their deputies, substitutes or assigns, for their defence and protection at all times and on all Just occasions hereafter, of attacking suddenly, Invading, expelling and by arms driving away, as ‘well by sea as by land, and by all means, all and singly those who, without the special license of the said Sir Willlam and his aforesaids, shall attempt to occupy these lands, or trade in the said province of New Scotland, or in any part of the same; and in like manner all other persons who presume to bring any damage, loss, destruction, injury or invasion against that province, or the inhabitants of the same: And that this may be more easily done, it shall be allowed to the said Sir William and his aforesaids, their deputies, factors and assigns to levy contributions on the adventurers and inhabitants of the same; to bring them together by proclamations, or by any other order, at such times as shall seem best to the said Sir William and his aforesaids; to assemble all our subjects living within the limits of the said New Scotland and trading there, for the better supplying of the ‘army with necessaries, and the enlargement and Increase of the people and planting of said lands: With full power, privilege, and liberty to the said Sir William Alexander and his aforesalds, by themselves or their agents of sailing over any seas whatever under our ensigns and banners, with as many ships, of as great burden, and as well furnished with ammunition, men and provisions as they are able to procure at any time, and as often as shall seem expedient ; and of carrying all persons of every quality and grade who are our subjects, or who wish to submit themselves to our sway, for entering upon such a voyage with their cattle, horses, oxen, sheep, go0ds of all kinds, furniture, machines, heavy arms, military instruments, as many as they desire, and other commodities and necessaries for the use of the same colony, for mutual commerce ‘with the natives of these provinces, or others who may trade with these plantations; and of transporting all commodities and merchandise, which shall seem to them needful, into our Kingdom of Scotland without the payment of any tax, custom and impost, for the same to us, or our custom-house offers, or thelr deputies; and of carrying away the same from thelr offices on this side, during the space of seven years. following the day of the date of our present charter; and to have this sole privilege for the space of three years next hereafter we freely have granted, and by the tenor our present charter grant and give to the sald Sir Walllam and bie aforesaids, according to the terms hereinafter mentioned.

And after these three years are ended, it shall be lawful, to us and our successors, to levy and exact from all goods and merchandise which shall be exported from this our Kingdom of Scotland to the said province of New Scotland, or imported from this province to our said Kingdom of Scotland, in any ports of this our kingdom, by the said Sir William ‘and his aforesaids, for five per cent. only, according to the old mode of reckoning, without any other impost, tax, custom or duty from them here- after; which sum of five pounds per hundred being thus paid, by the said Sir William and his aforesaids, to our officers and others appointed for this business, the said Sir William and his aforesaids may carry away the ‘said goods from this our realm of Scotland into any other foreign ports and climes, without the payment of any other custom, tax or duty to us or our heirs or successors or any other persons; provided also that said goods, within the space of thirteen months after their arrival in any part of this our kingdom, may be again placed on board a ship. We also give and grant absolute and full power to the said Sir William and his aforesaids, of taking, levying and receiving to his own proper use and that of his aforesaids, from all our subjects who shall desire to conduct colonies, follow trade, or sail to said land of New Scotland, and from the same, for goods and merchandise, five per cent. besides the sum due to us; whether on account of the exportation from this our Kingdom of Scotland to the said province of New Scotland, or of the importation from the said province to this our Kingdom of Scotland aforesaid; and in like manner, from all goods and merchandise which shall be exported by our subjects, leaders of colonies, merchants, and navigators from the said province of New Scotland, to any of our dominions or any other places; or shall be imported from our realms and elsewhere to the said New Scotland, five per cent. beyond and above the sum before appointed to us; and from the goods and merchandise of all foreigners and others not under our sway which shall be either exported from the said province of New Scotland, or shall be Imported into the same, beyond and above the said sum assigned to us, ten per cent. may be levied, taken and received, for the proper use of the said Sir William and his aforesaids, by such servants, officers or deputies, or their agents, they shall appoint and authorize for this business. And for the better security and profit of the said Sir William and his aforesaids, and of all our other subjects desiring to settle in New Scotland aforesaid, or to trade there, and of all others in general who shall not refuse to submit them- selves to our authority and power, we have decreed and willed that the said Sir William may construct, or cause to be built, one or more forts, strongholds, watch-towers, block-houses, and other bulldings, with ports and naval stations, and also ships of war: and the same shall be applied for defending the said places, as shall, to the said Sir William and his aforesaids, seem necessary to accomplish the aforesaid undertaking; and they may establish for their defence there, garrisons of soldiers, n addition to the things above mentioned; and generally may do all things for the acquisition, increase and introduction of people, and to preserve and govern the said New Scotland and the coast and land thereof, {in all its limits, features and relations, under our name and authority, as we might do if present in person; although the case may require a more particular and strict order than is prescribed in this our present charter and to this command we wish, direct and most strictly enjoin all our justices, officers and subjects frequenting these places to conform themselves, and to yield to and obey the cold Sir William and his aforesaids in all and each of the above-mentioned matters, both principal and related; and be equally obedient to them in their execution as they ought to be to us whore person the represents, under the pains of disobedience and rebellion, Moreover, we declare, by the tenor of our present charter to all Christian kings, princes any one, or any, from the said colonies, in the province of New Scotland aforesaid, or any other persons under their license and command, exercising piracy; at any future time, by land or by sea, shall carry away the goods of any person, or in a hostile manner do any injustice or wrong to any of our subjects, or those of our heirs or successors, or of other kings, princes, governors or states in alliance with us, then, upon such injury offered, or just complaint thereupon, by any king, prince, governor, state or their subjects, we, our heirs and successors will see that public proclamations are made, in any part of our said Kingdom of Scotland, just and suitable for the purpose, and that the said pirate or pirates, who shall commit such violence, at a stated time, to be determined by the aforesaid proclamation, shall fully restore all goods so carried away ; and for the said injuries shall make full satisfaction, so that the said princes ‘and others thus complaining shall deem themselves satisfied. And, if the authors of such crimes shall neither make worthy satisfaction, nor be careful that it be made within the limited time, then he, or those who have committed such plunder, neither are nor hereafter shall be under our government and protection; but it shall be permitted and lawful to all princes and others whatsoever, to proceed against such offenders, or any of them, ‘and with all hostility to invade them.