From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

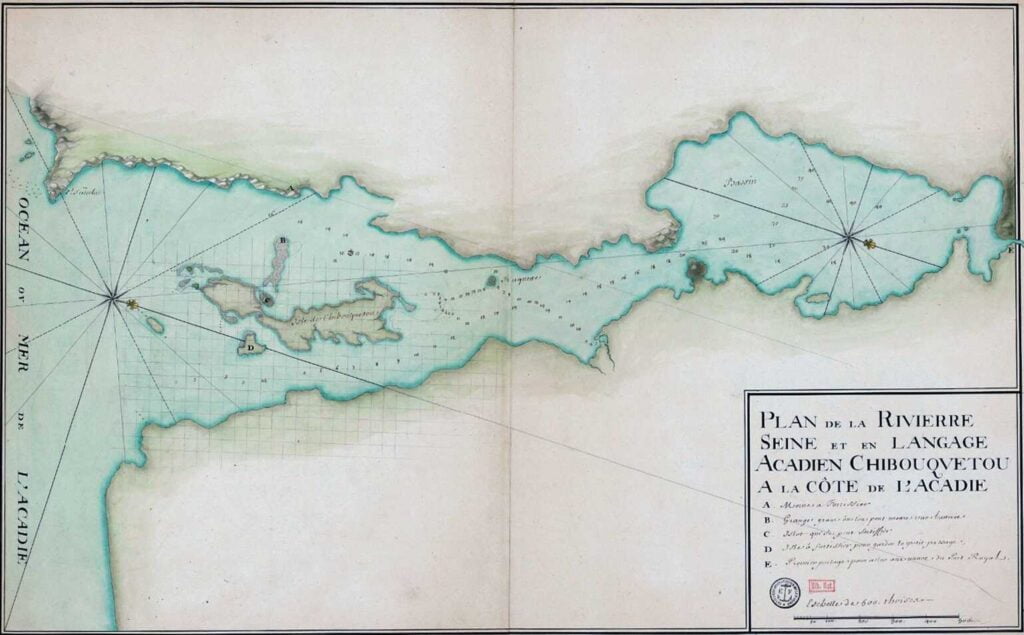

After the Treaty of Utrecht, the first recorded proposal for a settlement on the Dartmouth side from British officials originated with Captain Thomas Coram of London in 1718. One of the districts selected for establishing colonists was “northeast of the harbor of Chebucto”. Massachusetts influence opposed this plan as being detrimental to their fisheries.

As an aside, Martin’s account of Captain Thomas Coram in 1718 and his attempt to establish settlements “northeast of the harbor of Chebucto” isn’t supported by “An historical and statistical account of Nova Scotia” by Thomas Chandler Haliburton, where it is stated that the settlement was instead planned for a location “upon the sea coast, five leagues S.W. and five leagues N.W. of Chebucto”, not on the Dartmouth side. (Five leagues is approximately 28 km). It did make me wonder about the “Bayer’s Lake mystery walls” and whether they are remnants of a such a settlement, made regardless of a lack of authorization from Colonial authorities.

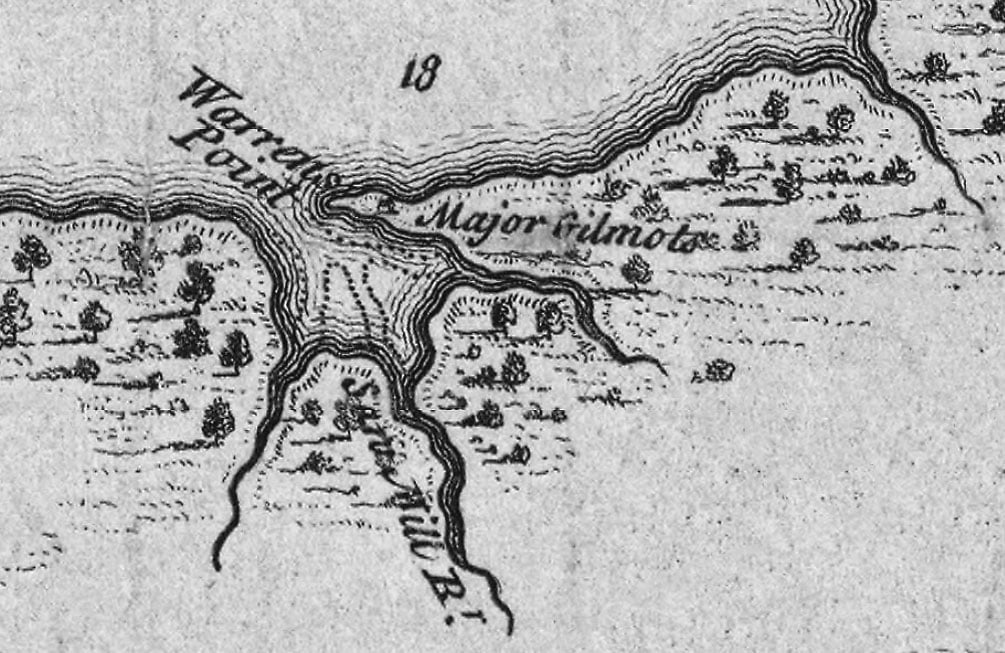

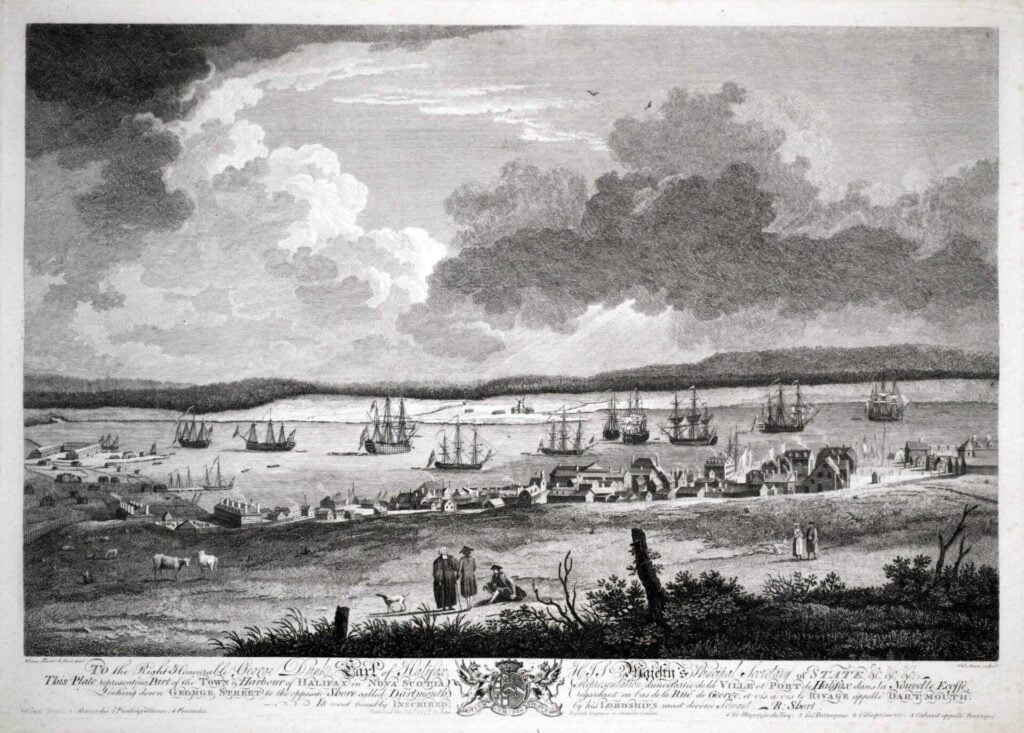

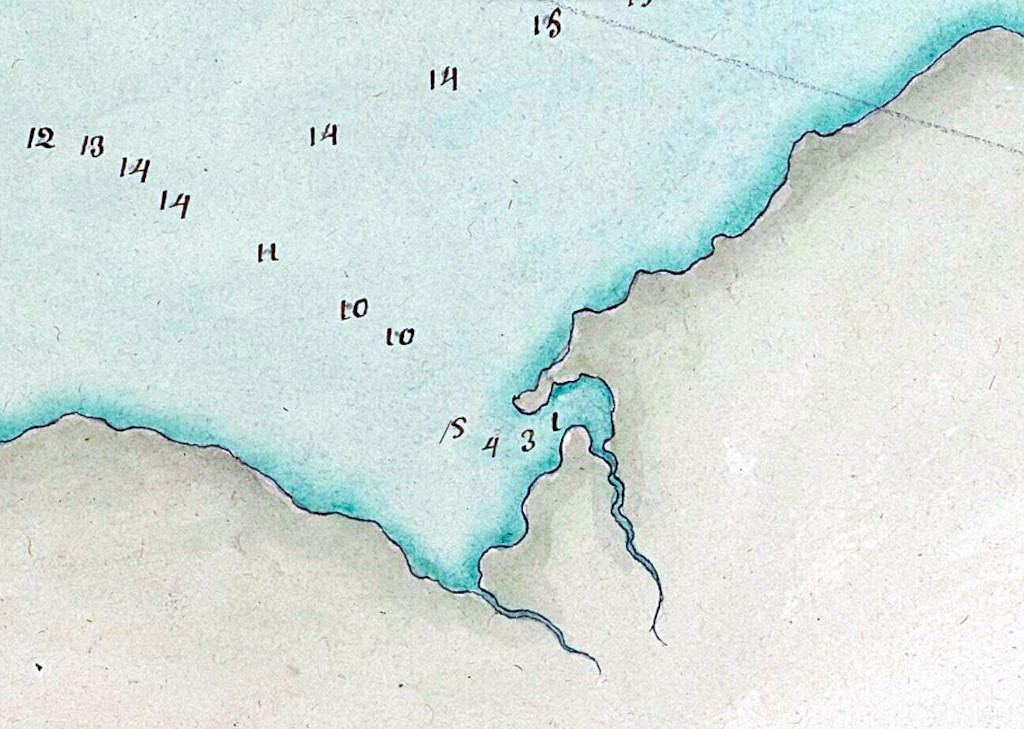

When Hon. Edward Cornwallis set out to settle Halifax in 1749, he carried a complete plan of the harbor, the Basin and the surrounding shores, which had been previously surveyed by British Admiral Durell. The latter’s information about useful places on the eastern side must have been noted, and probably soon inspected by Cornwallis, for he does not lose much time in sending men over to the present Canal stream with the necessary gear to erect the sawmill.

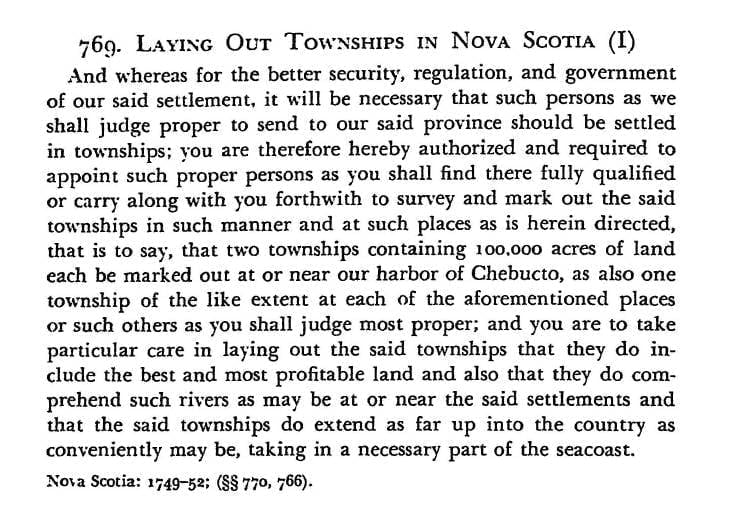

Cornwallis also carried with him royal instructions that called for the founding of two townships “…containing 100,000 acres of land each be marked out at or near our harbor of Chebucto”.

New York, Octagon Books, 1967. https://archive.org/details/royalinstruction028364mbp/page/n93/mode/2up

There were about 30 men quartered at the sawmill during the winter of 1749-1750. More were living aboard the “Duke of Bedford” and on an armed sloop, which were anchored in the Cove nearby. It must have been an especially severe season, for the two ships were frozen-in so that ice had to be broken every night to prevent incursions from the shore.

Major Ezekiel Gilman was in charge of the sawmill. This pioneer local industry seems to have been an utter failure. In April 1750 Cornwallis reported to London that the mill had been his “constant plague from the beginning. We have never had one board from it”. This was partly due to Mr. Gilman’s bad management.

On the other hand, the Governor makes more encouraging reports on a second undertaking, presumably carried out on the eastern side of the harbor. In July 1750 he writes that “30,000 bricks have been burnt here which prove very good”.

Brick clay can still be clawed out of the sloping bank along the railway from Tupper Street to the Passage. Mott’s Pottery used tons of it. Until the 1880’s the Wellington brickyard flourished near the Seaplane base at Imperoyal. A record in the New York Public Library says that [Mi’kmaq] before going into battle, used to appear more ferocious by smearing their faces with “that red vermillion found on the east side of Chebucto”.

This clay belt must extend under the surface of downtown Dartmouth, because excavations at 85 Portland Street brought up quantities of plastic mud from the bottom of a 20-foot well, unearthed in the back yard.

The earliest accounts of the colonists destined to become our first citizens have been obtained from the Secretary of the Public Record Office in London. Their 1750 files disclose that the “Alderney” was getting ready to sail for this port from Gravesend on May 25. On July 6, she was reported at Plymouth, having put in there on account of contrary winds.

Evidently then, the pioneer settlers of Dartmouth sailed from the same English port as did the Pilgrim Fathers in 1620.

The actual day that the Alderney reached Halifax harbor is not definitely known. It was not before August 19, and not after the September 3rd, because Governor Cornwallis’ Council met on the latter date to select a location for the new settlers. The sites suggested were at the head of Bedford Basin, at the North West Arm, in the present Woodside-Imperoyal section and near the Saw Mill. The last mentioned was finally chosen. (The dates given are all old style. To conform to the present calendar, eleven days should be added).

The Alderney was a ship of 504 tons and the number of passengers on board totaled 353. No deaths were recorded on the voyage, mostly because immigrant vessels were by that time fitted-up with the newly-invented system of ventilation. The largest vessel among Cornwallis’ transports of 1749 was the “Wilmington” yet she carried only 340 colonists. Stretching space on the Alderney must have been very limited.

As a conjecture, the hold of the Alderney was also jammed with family heirlooms, household utensils, bedding, clothing, perhaps pet dogs, cats and parrots in the midst of seasick youngsters and oldsters inhaling the garlicky atmosphere so characteristic of old-time steerage accommodations. Hence, transatlantic voyages on these lurching and leaning sailing ships weren’t just exactly luxurious.

How our town came to be called Dartmouth is not definitely known. Dartmouth, England, was probably named for the first Earl of Dartmouth, George Legge the celebrated Admiral. He stood in high favor until suspected of treasonable correspondence with James II. Then he was imprisoned in the Tower for three months until his death in 1691.

William Legge, the second Earl of Dartmouth, was Keeper of the Privy Seal, and perhaps held that office in 1750 when he died. The late Harry Piers, who edited Mrs. Lawson’s History, says that our town was doubtless named after this man.

On the other hand, the name may have come from Dartmouth in Devon on the west coast of England. The 1950 guidebook of the latter town informs us that people from that district of the river Dart, migrated to Newfoundland from earliest times, probably to prosecute the fisheries.

Governor Cornwallis’ reports of 1750 indicate that he is anxious to obtain fishermen in order to make his colony self-sustaining. He hoped to have “people from the West of England next year for the fishery. Mr. Holsworth of Dartmouth sent people here this year, they have cleared ground to begin upon the Fishery next year”.

Dartmouth, England, guidebook states that the Holdsworth family occupied the post of Governor of Dartmouth Castle in hereditary succession until 1832. The descendants still live in Devon, according to recent information received from Mr. B. Lavers ex-Mayor of Dartmouth, Devon.

The town plan as laid out in 1750 comprised 11 oblong-shaped blocks, mostly 400 feet long by 200 feet wide. Each building lot was 50 by 100 feet. Reference to the cut shows that all the streets running north and south, lead to the Point, which is the front part of the settlement. The northern boundary seems to be the present line of North Street. The southern boundary is the present Green Street (once between Portland Street and Front Street), if it were produced through to Commercial St (present Alderney Drive). All the area from that line to the Point would be the 10 acre grant of Benjamin Green.

The eastern boundary is at Dundas Street, and from there the present Queen Street extends through the middle of the plot to Commercial St. But Portland and Ochterloney Streets come to an end at King Street. (No street names appear on first plan).

From that point all the way to Eastern Passage, larger areas ranging from 60 to over 200 acres, and fronting on the shore, were granted to people prominent among Cornwallis’ settlers. Adjoining Davison’s was that of Samuel Blackden (or Blagdon); next was John Salisbury at Hazelhurst shore, then Charles Lawrence in the Department of Transport vicinity; William Steele, Richard Bulkeley, Byron Finucane, Joseph Gerrish, Jacob Hurd, Charles Morris, Leonard Lockman, Rev. Aaron Cleveland, Rev. Mr. Tutty and others.