This contains the most charitable and interesting sections of the book. Many of these vintage titles I’ve found contain so much that is superfluous or offensive that I try to be selective, not to paint a pretty picture, but to find anything that approached a realization of the gravity of the situation. I don’t think these excerpts represent the totality of the opinion at the time, or the prevalent opinion, so I don’t take them as broadly representative. They were representative enough, however, to have found their way into print.

An interesting connection I noticed was what I think is a reference to Cain and Abel, below (“And when they shall have passed away, and their very name is forgotten by our children, will not the voice of our brother’s blood cry unto God from the ground? And in the Day of Judgment when all past actions will be brought to light, and the despised [indigenous person] will stand on a level with his now more powerful neighbor, then as poor and as helpless as himself; when the Searcher of Hearts shall demand of us, “Where is thy brother?”, how shall we answer this question, if we make not now one last effort to save them!”).

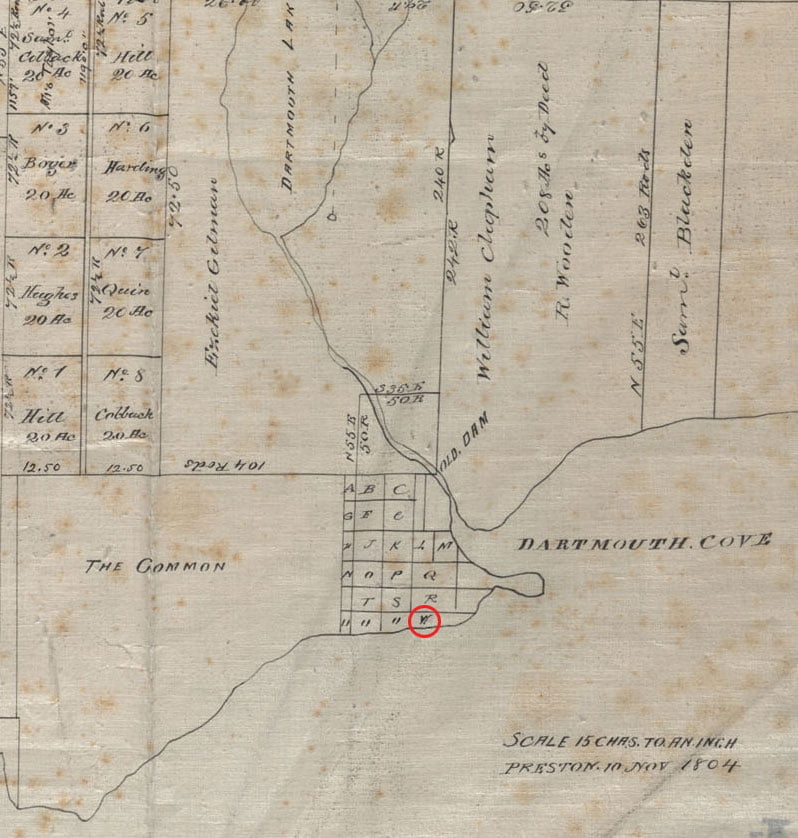

This is reminiscent of Quaker Joshua Evans of West Jersey, who visited Dartmouth in 1795, 55 years earlier, who often preached “something is yet due the [Mi’kmaq] for land wrongfully taken”. He would often compare the blood of Abel, calling out for revenge, to the blood of slaves and [Mi’kmaq].

Something else I am interested in is the contention here that the Mi’kmaq language resembles Hebrew, “especially in the suffixes by which the Personal Pronouns are connected in the Accusative Case, with the Verb.” Truly fascinating.

“Drunkenness is fearfully prevalent … though not so much of late years as formerly; and other vices resulting from the proximity of what we proudly call “civilization”, a civilization which too often seeks its own interest and gratification, regardless of either the temporal or spiritual interests of others; caring for neither soul or body.”

“Chiefs are … duly elected. The [Mi’kmaq] assemble on such occasions to give their votes, and any one who knows any just cause why the candidate should not be elected, is at liberty to state it. Councils too are held, to which ten different tribes, extending from Cape Breton to Western Canada, send their delegates; and they seem to consider the affair as important as it ever was.”

“The language of the [Mi’kmaq] is very remarkable. One would think it must be exceedingly barren, limited in inflection, and crude. But just the reverse is the fact. It is copious, flexible, and expressive. Its declension of Nouns, and conjugation of Verbs, are as regular as the Greek, and twenty times as copious. The full conjugation of one Micmac Verb, would fill quite a large volume! … in other respects the language resembles the Hebrew. Especially in the suffixes by which the Personal Pronouns are connected in the Accusative Case, with the Verb.”

“We have treated them almost as though they had no rights, and as if it were somewhat doubtful whether they even have souls.”

“…they have some knowledge of Astronomy. They have watched the stars during their night excursions, or while laying wait for game. They know that the North star does not move, and they call it “okwo-lunuguwa kulokiiwech,” “the North star.” They have observed that the circumpolar stars never set. They call the Great Bear, “Muen” the bear. And they have names for several other constellations. The morning star is ut’adabum, and the seven stars ejulkuch. And “what do you call that?” said a venerable old lady a short time ago, who with her husband, the head chief of Cape Breton, was giving me a lecture on Astronomy, on nature’s celestial globe, through the apertures of the wigwam. She was pointing to the “milky way”. “Oh we call it the milky way — the milky road,” said I. To my surprise she gave it the same name in [Mi’kmaq].”

“Now all these facts relate to the question of the intellectual capacity of the [Mi’kmaq]; the degree of knowledge existing among them; and the possibility of elevating them in the scale of humanity. If such be their degree of mental improvement, with all their disadvantages, what might they not become, were the proper opportunity afforded? Shame on us! We have seized upon the lands which the Creator gave to them. We have deceived, defrauded, and neglected them. We have taken no pains to aid them; or our efforts have been feeble and ill-directed. We have practically pronounced them incapable of improvement, or unworthy of the trouble; and have coolly doomed the whole race to destruction. But dare we treat them thus, made as they are in the image of God like ourselves? Dare we neglect them any longer? Will not the bright sun and the blue heavens testify against us? And will not this earth which we have wrested away from them, lift up its voice to accuse us? And when they shall have passed away, and their very name is forgotten by our children, will not the voice of our brother’s blood cry unto God from the ground? And in the Day of Judgment when all past actions will be brought to light, and the despised [indigenous person] will stand on a level with his now more powerful neighbor, then as poor and as helpless as himself; when the Searcher of Hearts shall demand of us, “Where is thy brother?” how shall we answer this question, if we make not now one last effort to save them! We will make such an effort. We are doing so, and God is with us. He will crown our labours with success. We will implore forgiveness for the past, and wisdom and grace for the future.”

Rand, Silas Tertius. “A short statement of facts relating to the history, manners, customs, language, and literature of the Micmac tribe of Indians” [Halifax, N.S.? : s.n.] 1850. https://archive.org/details/cihm_39506