The book delves into the historical and social landscape of Nova Scotia, particularly focusing on religious movements, governance, and societal norms. It begins with a discussion on religious fervor in the late 18th century, influenced by New England revivalism, and the subsequent tensions between Anglicanism and dissenting sects. The text explores the impact of legislation on religious practices and the social dynamics between different religious communities, highlighting the presence of dissenters and the struggles they faced.

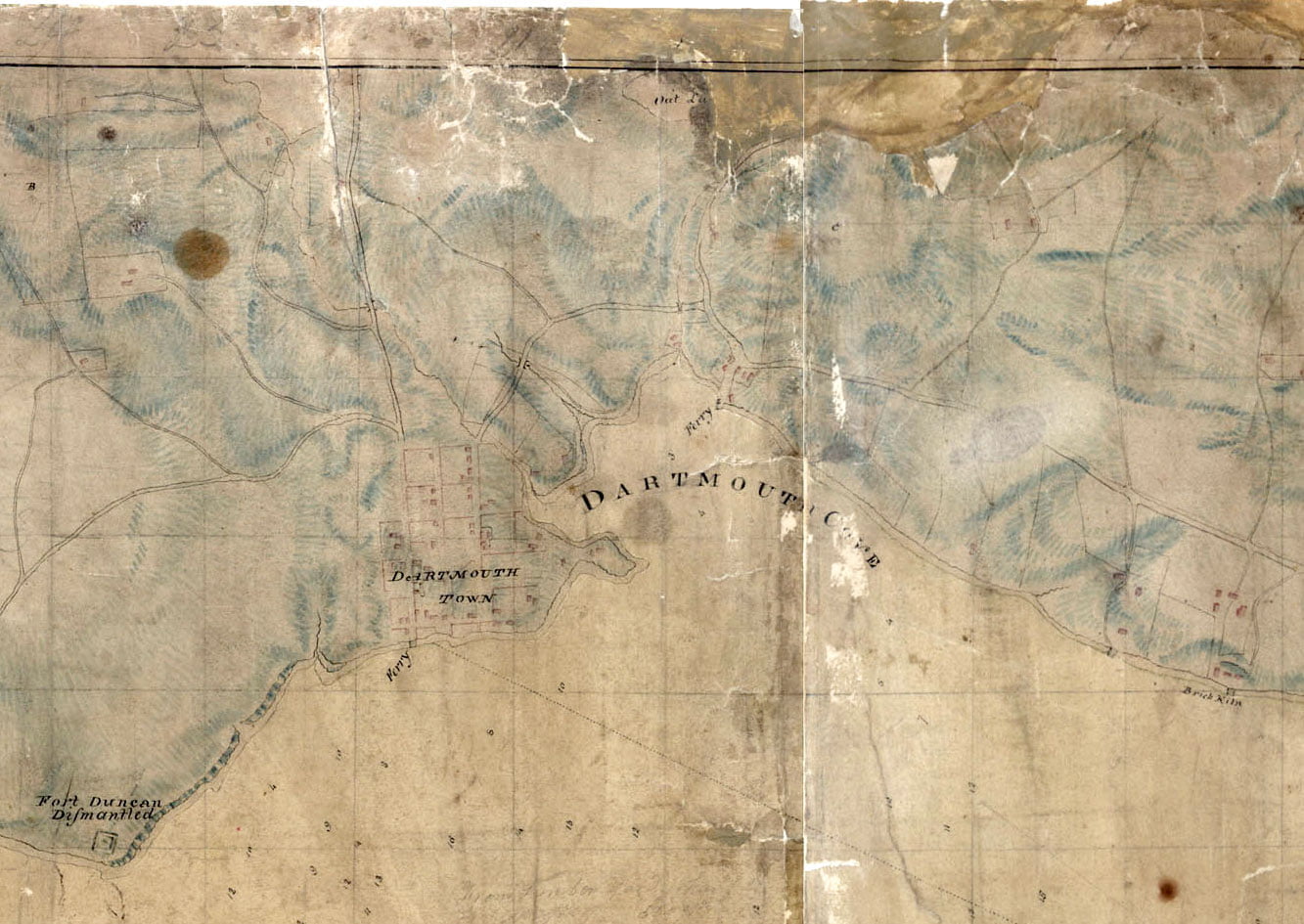

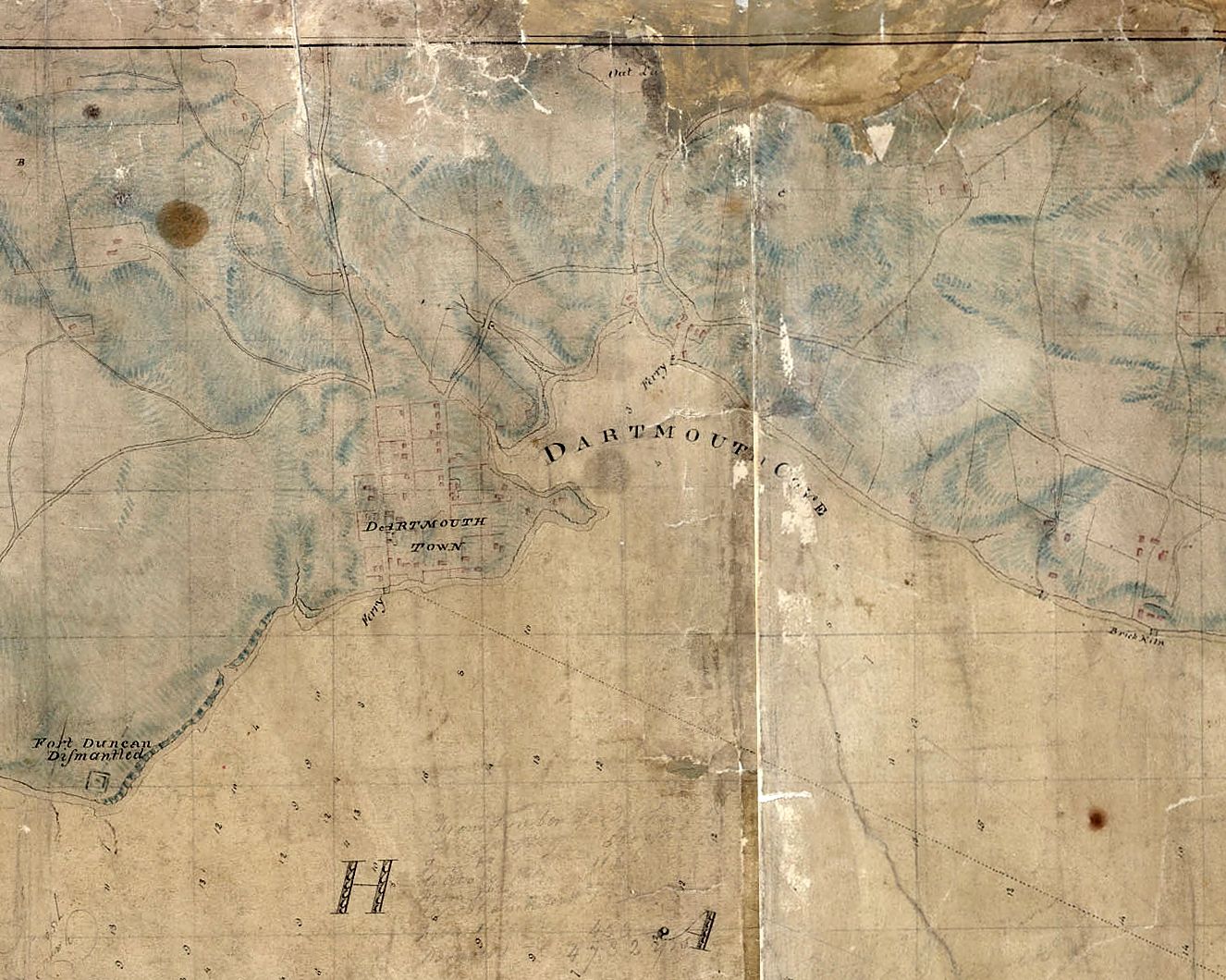

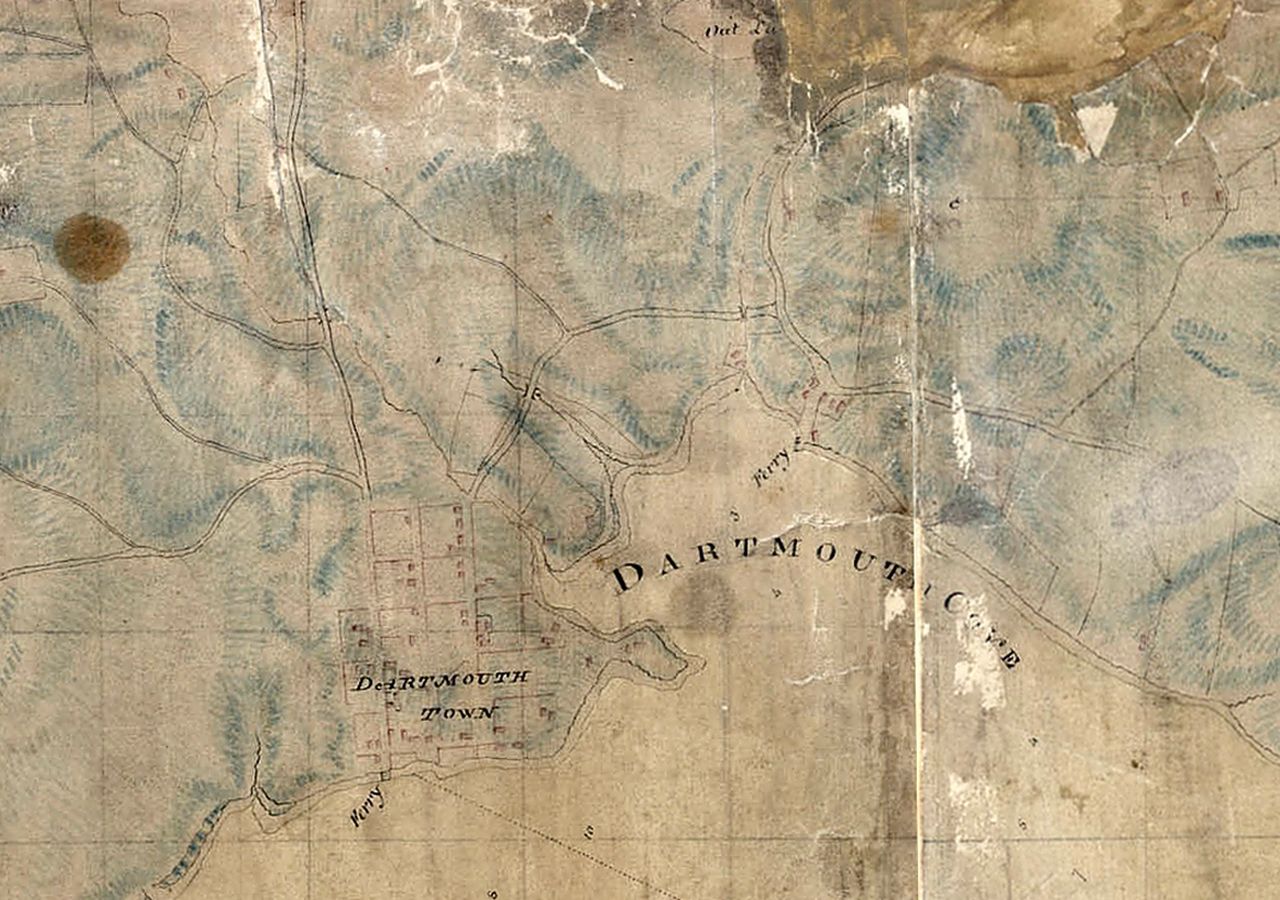

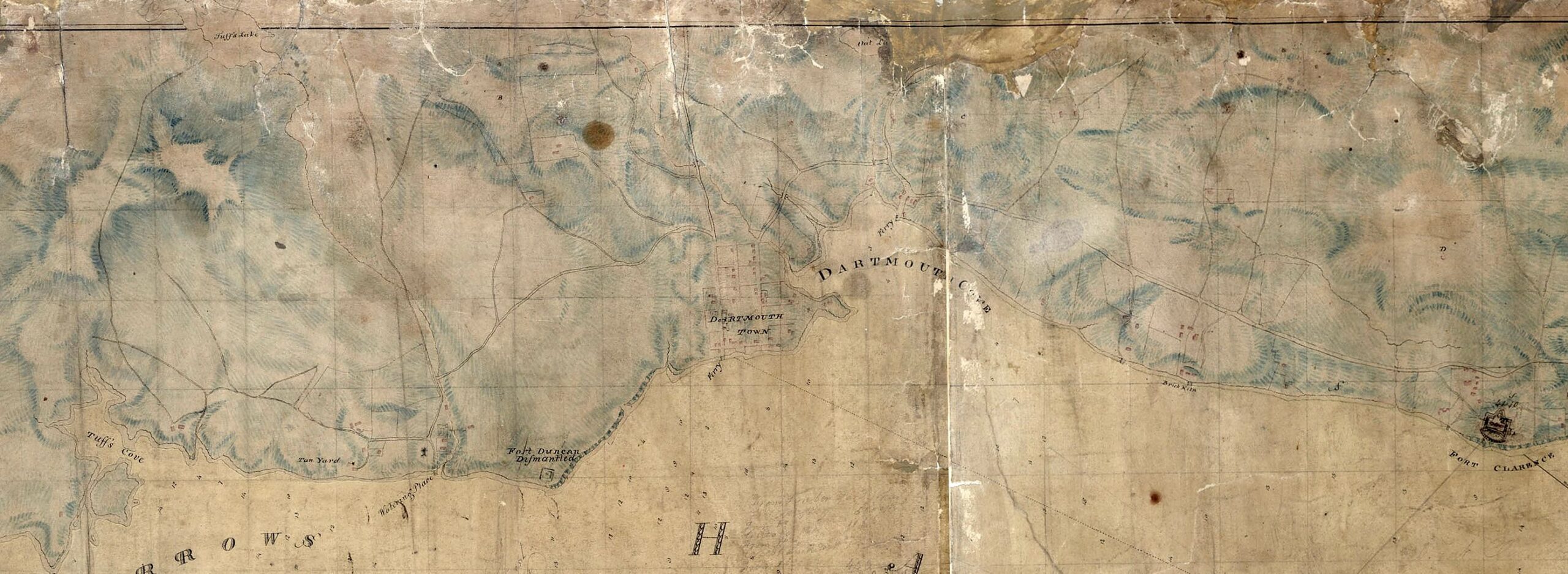

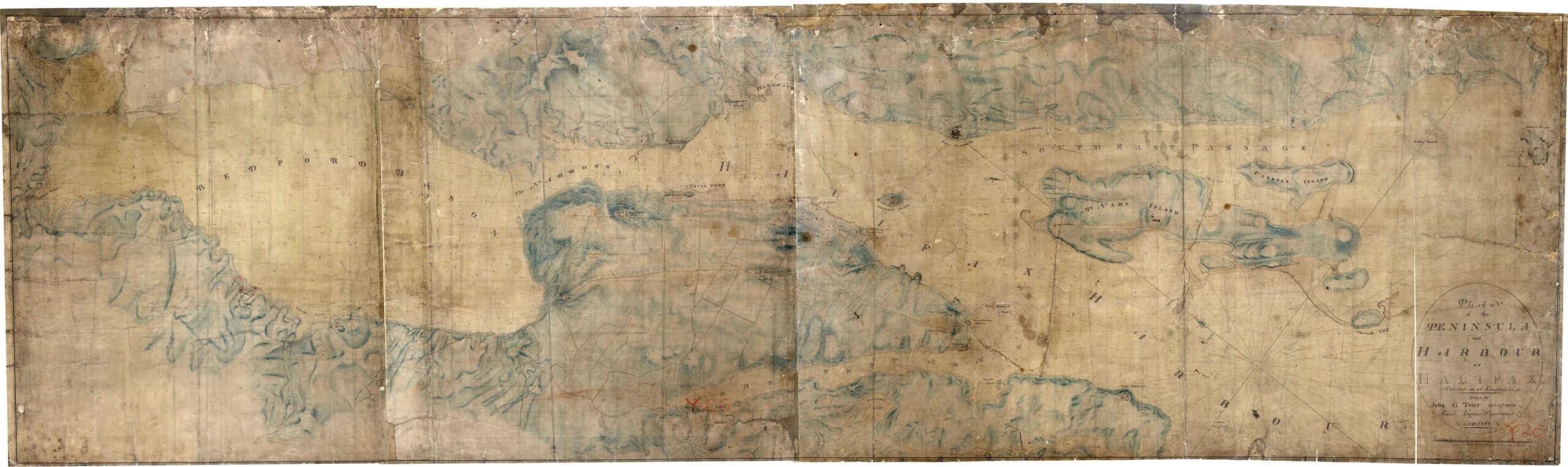

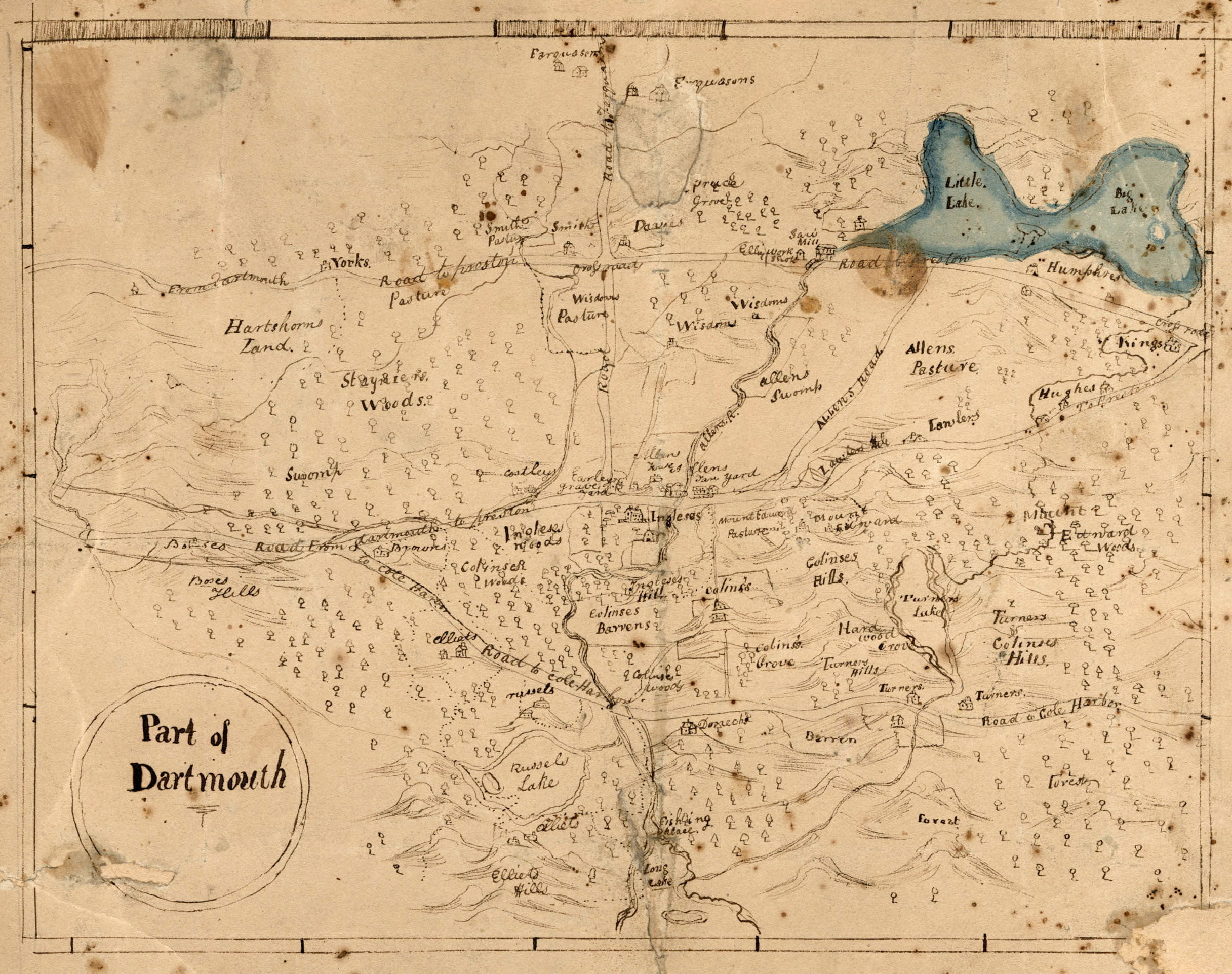

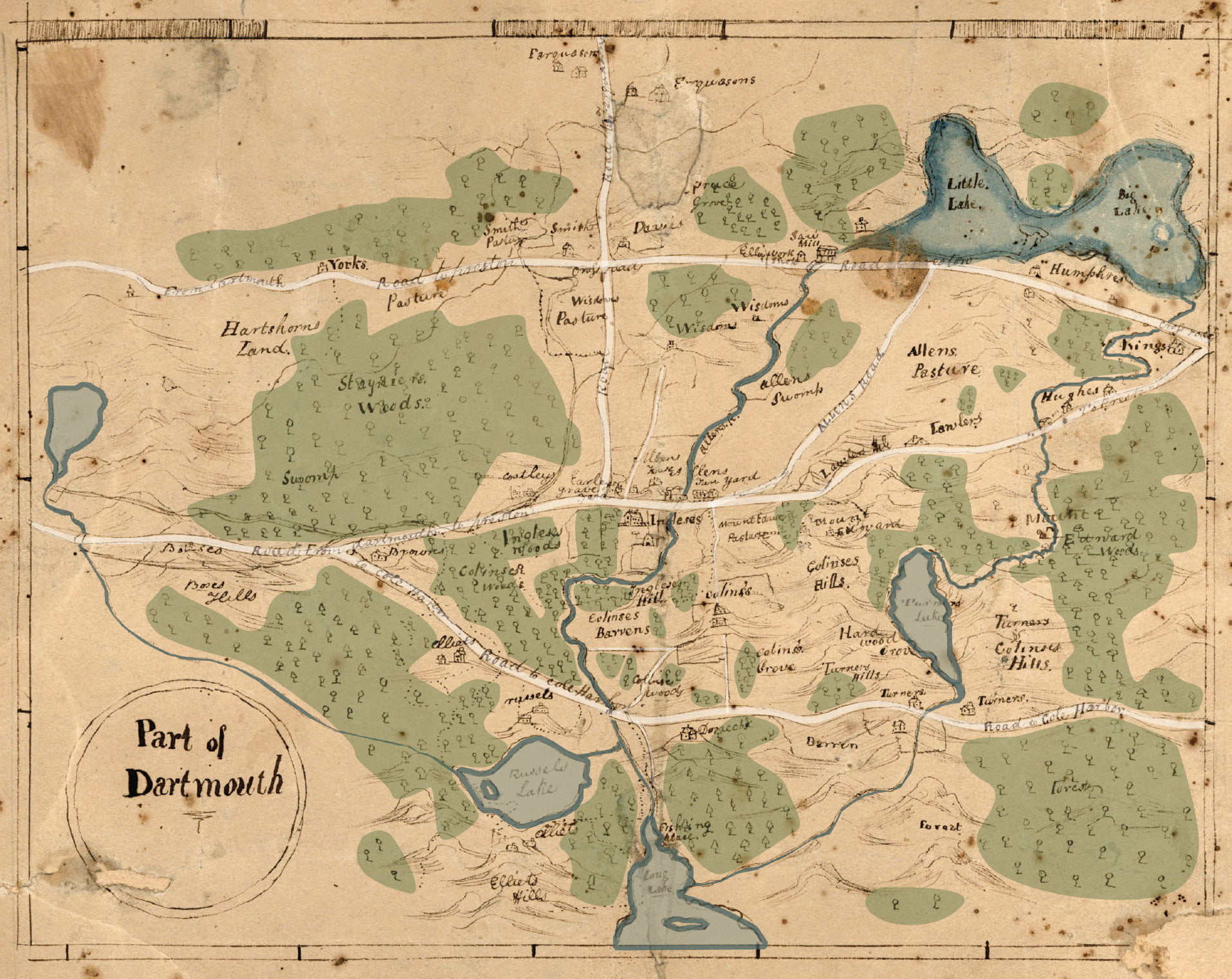

Furthermore, it describes the migration patterns from New England to Nova Scotia, emphasizing the collective nature of settlement and the adaptation of New England practices in township organization. The role of government intervention in local governance and its effect on the development of town meetings is examined. Additionally, societal issues such as slavery, education, and moral conduct are addressed, shedding light on the complexities of early Nova Scotian society.

The passage also discusses the repercussions of the American Revolution on religious institutions and the political climate of Nova Scotia, showcasing the diverse responses of ministers and communities to the conflict. It concludes with reflections on the resilience of Nova Scotians amidst uncertainty and the efforts of religious leaders like Henry Alline to provide spiritual guidance during challenging times.

“In the year 1799 the Bishop of Nova Scotia reported to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts that the Province was being troubled by “an enthusiastic and dangerous spirit” among the sect called “Newlights”, whose religion seemed to be a “strange jumble of New England Independency and Behmenism.” Through the teaching of these “ignorant mechanics and common laborers”, the people were being excited to a “pious frenzy,” and a “rage for dipping” prevailed over all the western counties. It was further believed by the Bishop and the Anglican clergy that these sectaries were engaged in a plan for “a total Revolution in Religion and Civil Government.”

“…as Bishop Inglis recognized, the movement was a continuation of the great revival of religion which occurred in New England between 1740 and 1744, it may be properly called “The Great Awakening in Nova Scotia.”

“Although laws — such as 1758’s an Act for the establishment of religious public Worship in this province, and for suppressing popery — were intended only for the proper regulation of the Church of England, and although the Assembly took care to insert a clause in the act providing for the liberty of conscience and freedom of worship for Protestant Dissenters (32 Geo. II, Cap. V, ii), the remaining sections of the act contain very stringent laws against “popish priests,” providing “perpetual imprisonment” for any offenders found within the province after Mar 25, 1759, and a fine of £50 and the pillory for any person harboring, relieving, concealing or entertaining such a priest. These harsh enactments were omitted from the revised laws of 1783, but Test Oaths were required of all Catholics until 1827. The Anglican church was not disestablished until 1851, nevertheless, there was enough of the coercive in the law to arouse the suspicion of the New Englanders… Were not these laws respecting unlicensed teachers and preachers similar to those aimed at the itinerants and exhorters in Connecticut and Massachusetts?”

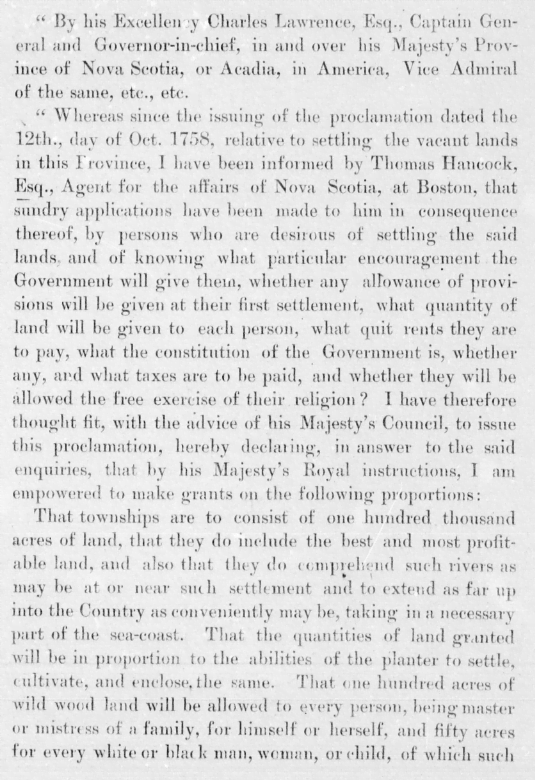

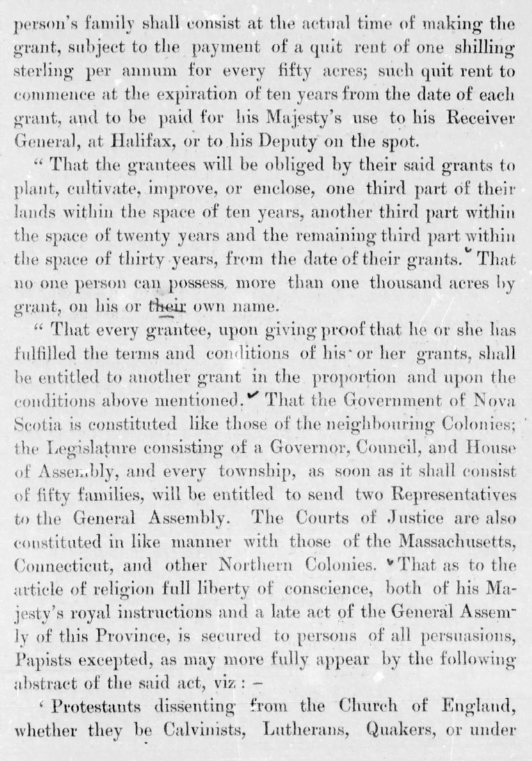

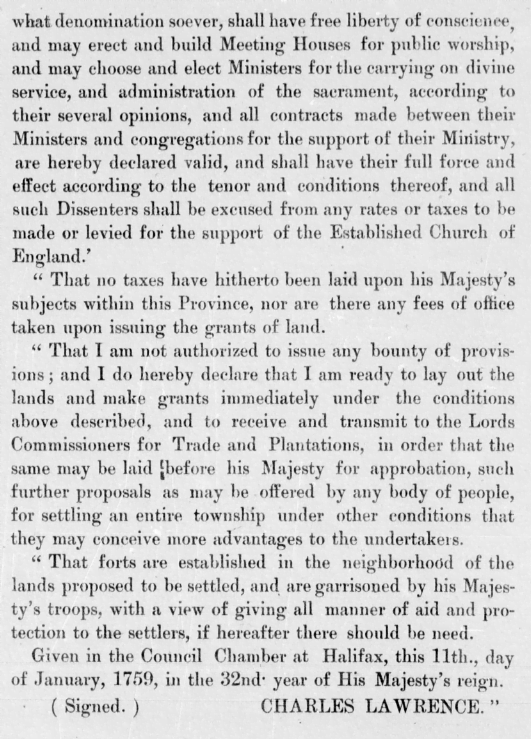

“…Governor Lawrence was led to issue a second proclamation on January 11, 1759. This document contained the solemn assurances of the government upon the subject of civil and religious liberties within the province, which early won for it the title “The Charter of Nova Scotia.” (T.C. Haliburton, An Historical and Statistical Account of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1829), I, 220. A copy of the original proclamation may be seen in the John Carter Brown Library, Providence, R.I. It also appeared in Boston News-Letter, Feb 15, 1759.)

Regarding religion the proclamation declared:

…full liberty of conscience, both of His Majesty’s royal instructions and a late act of the General Assembly of this Province, is secured to persons of all persuasions, Papists excepted, as more fully appears from the following extract of the said act, viz: “Protestants dissenting from the Church of England, whether they be Calvinists, Lutherans, Quakers, or under what denomination soever, shall have free liberty of conscience, and may erect and build Meeting Houses for public worship, and may choose and elect Ministers for the carrying on of Divine services and administration of the sacrament, according to their several opinions, and all contracts made between Ministers and Congregations for the support of their Ministry are hereby declared valid, and shall have their full force and effect according to the tenor and conditions thereof, and all such Dissenters shall be excused from any rates or taxes to be made or levied for the support of the Established Church of England.”

“With the opening of the Ohio country in 1768, immigration from American colonies practically ceased, and Nova Scotia remained a back-water untouched by the main currents of American migration until the flood-tide of Loyalist refugees burst in upon it at the close of the Revolutionary war. Immigration from the other side of the Atlantic, however, continued.”

“The movement from New England to Nova Scotia was social and not individualistic. Associations of families and not lone pioneers, made the plans, sent their representatives… When they reached their new township they met together, chose their own officers, and laid out their own lands and town-plot. This was all done in accordance with old New England practice. (Cf., R.H. Akagi, The Town Proprietors of the New England Colonies (Philadelphia, 1924), esp. Ch. 1, 3 & 4.)”

“The term “proprietor” is very familiar in New England history. The proprietors were the owners of the land and were responsible collectively for the improvement of the new plantation. “More specifically they were responsible for inducting and enlisting newcomers, for locating home lots and dwelling houses, for building highways and streets, for subdividing the adjacent arable land, and subjecting the meadow and forest, for a time at least to a common management. Records of proprietors meetings at Falmouth, Cornwallis, and Horton show that the Nova Scotia immigrants followed the New England custom.

At the first meeting of the Falmouth proprietors, on June 10, 1760, Shubael Dimock, a former deacon of the Separate Church in Mansfield, Connecticut, was elected Moderator, and, according to custom, a standing committee of three was appointed to manage the prudential affairs of the community. This committee laid out the lands as they had been laid out for over a century in New England; two hundred acres for a Common, sixty acres for a town site and certain tracts for a meeting house, cemetery, school, and for the first resident minister.”

“In one very important respect, however, the Nova Scotian proprietors differed from those in New England. The number of lots or shares in each township was determined by the government and not by the proprietors meeting, and each proprietor received only his exact share; the lands remaining in the township then still remained in the hands of the Crown, and were granted to new proprietors by the Lands Office at Halifax and not by the local proprietors meeting.”

“In 1766 there was a remonstrance from the principal inhabitants of Halifax to the Lords of Trade because “all the scum of the Colonies” was being admitted to the province which they said had been “inundated with persons who are not only useless but burdensome,” and that the passage money of “persons from goals, hospitals and work-houses” was actually being paid by the other colonial governments… There is ample evidence, however, to show that there were among the pioneers self-reliant and socially assured leaders who, given the advantages of a new land, soon forged ahead and achieved prosperity and independence for themselves.”

“The neatly planned towns, with their regularly laid out streets and village greens, did not materialize. Instead, the shortest path across the fields of an absentee owner, or of a deserted homestead, connected the irregularly scattered dwellings of the village.

Because of direct government interference, the associations of proprietors in Nova Scotia never developed into the influential town-meetings which were so familiar in New England. As early as 1761, on the recommendation of Governor Belcher, the Lords of Trade disallowed an “Act enabling proprietors to divide lands held in common,” which had been passed by the first assembly. Belcher’s motive… was to extend the authority of the central government over the townships…

The fate of town-meetings was bound up with the intrigues of the Halifax circle. Instead of permitting the freeholders to elect their own officers, it was arranged that the grand juries of the four principal counties should nominate candidates for the local offices and then the local Justices of the Peace choose from among the nominees the men who should finally be appointed. In this way the offices of the townships were kept in the hands of the friends of the government, or at least that group of enterprising men who held key positions in council. About the only power left to the town meetings was the care of the poor. The change did not pass without protest, but on the whole the towns were too weak to defend “the rights and liberties of Englishmen.”

In 1770 the town meeting of Truro objected to the officers chosen to govern it. Liverpool and other towns also made complaints, but a warning that the Attorney-General had been instructed to prosecute persons who called “Town Meetings for Debating and Resolving on Several Questions Relating to the Laws and Government of this Province” seemed to have a quieting effect. The new settlements were too scattered to unite in any effort to preserve their liberties, and too poor to carry on the struggle. Those who might have been their leaders already held offices under the centralized system and shared in its profits.

It was this lack of leadership, organization, and experience, as well as their remoteness and poverty, which to a great extent determined Nova Scotia’s attitude during the War of Independence. There can be little doubt that Governor Belcher’s policy “prevented the formation of some twenty little republics in western Nova Scotia, and it enabled the central government to establish communications with the townships and to retain a check upon their activities. It also accelerated the moral and social decline which has already been observed.”

“Drunkenness seems to have been the most prevalent evil. Provincial statutes, comparable to the “Blue Laws” of New England, provided severe sentence for all breaches of the criminal code, and for such offenses as profanity, or absence from Church. Church wardens were ordered to walk the streets during the time of divine worship to discover the delinquents. (1 Geo. III, Cap. 1, Acts of the General Assemblies.)

Slavery was practiced by those who could afford it. The Nova Scotia Gazette from time to time carried advertisements such as the following:

Ran Away

On Monday the 10th., of June last, between the hours of 9 and 10 at night, a negro woman named Florimell, she had on when she went away, a red Poppin Gown, a blue baize outside Petticoat, and a pair of Men’s shoes, she commonly wears a handkerchief around her Head, has scars on her face, speaks broken English, and is not very black.. 1 Guinea Rwd. and all charges for their trouble. (Nova Scotia Gazette, July 9, 1776. See Also Ibid., May 28, 1776. The price of slaves varied from £20 to £75 N.S. Money. Cf., T.W. Smith, “The Slave in Canada” N.S.H.S., X, 11 ff.)

In addition to household slaves it was customary for Town meetings to farm-out the local poor. The wealthier rate-payers “bid-off” these unfortunates, who then went to work for them in return for food, lodging and clothes. The town-charges thus became a form of indentured servants, and in addition the good citizen who took them received from the town a sum of money equivalent to his “bid”. (Eaton, Kings County, 162.)”

“Henry Alline, who before his conversion was a leader among the younger set in Falmouth, has left accounts of evenings spent at neighbor’s homes, where the young people amused themselves singing “carnal songs,” telling stories, and causing great mirth by imitating the “extra-ordinaries” of the Newlights, whom some of them remembered before 1760 in Connecticut.”

“In 1765 the Assembly passed An Act Concerning Schools and Schoolmasters, which required all would be teachers to be examined by a minister or two justices of the peace, and to present a certificate of morals and good conduct, signed by at least six inhabitants. He must also take the oath of allegiance. By the same act, boards of school trustees were set up to administer the lands reserved in the original plans of every township for a school. (6 Geo. III, Cap vii, Acts of General Assemblies. The effect of the Act was to place the control of the school lands in the hands of the Anglican clergy, from which they were wrested only after a long and bitter struggle ending in an appeal to the Privy Council in the middle of the nineteenth century. Cf., Eaton, Kings County, 269,270.)”

“…the majority of the population of the province before 1784 were Dissenters. In Halifax, even before the great New England migration of 1760, settlers from the American colonies composed a large and influential part of the community. A protestant Dissenter’s meeting House, known as Mather’s Place in honor of the well-known Boston divines, was erected in 1750 and was supplied by Congregational ministers until the end of the revolution.” (Walter Murray, “History of St. Matthew’s Church,” N.S.H.S., XVI, 137-170.)

“The final blow to congregationalism in Nova Scotia was the American Revolution. (M.W. Armstrong-“Neutrality and Religion in Revolutionary Nova Scotia,” The New England Quarterly, Mar. 1946, 50-62). To the already demoralized and disintegrating churches were now added the calamities of a further loss of ministers, an increased uncertainty because of privateers and possible invasion, and the gnawing uneasiness of a divided loyalty.

By 1775, half of the Congregational pulpits were already vacant. During the war, some of the ministers evinced republican sympathies, but were instantly silenced by the government. The Rev. Benaiah Phelps of Cornwallis was accused of being “an uncompromising Whig” and left the province in 1777. The Rev. Seth Noble of Maugerville, after months of seditious activity, fled to Machias. The Rev. Arzarleh Morse of Granville seems to have been peaceable enough, but at the close of the war gave up his trying charge and returned to New England. John Frost who had been ordained by the church of Jebogue was reported to the Provincial Council in the month of August, 1775, for interfering with a muster of the militia at Argyle and for publicly expressing “his hopes and wishes that the British forces in America might be returned to England confuted and confused. (Minutes of the Council, Aug. 23, 1775. Mr. Frost was deprived of his office as justice of the peace and died shortly after.) The Rev. John Seccomb of Chester was also charged before the Council with “preaching a Sermon tending to promote Sedition and Rebellion,” and with “praying for the Success of the Rebels.” (Ibid., Dec 23, 1776, Jan. 6, 1777) He was placed under a bond of £500 for his future good behavior and henceforth had an uneventful career. Only the Rev. Israel Cheever of Liverpool, “a hard drinker,” and the Rev. Johnathan Scott, the farmer-pastor of Jebogue, avoided the political pitfalls of the times and labored to preserve the New England way in Nova Scotia.

The Presbyterian churches were not so seriously affected by the war… Only the Rev. James Lyon of New Jersey, who had once advised the patient Mr. Bruin Romcas Comingoe “To avoid a party spirit in politics,” showed republican sentiments. Migrating to Machias, Maine, he became the center of plots and schemes to capture Nova Scotian villages and plunder British shipping in the Bay of Fundy. There is some evidence that some of the Ulster settlers in Colchester County shared Parson Lyon’s views. Writing from Halifax to the Secretary of State in 1776, General Massey said, “If you Lordship will pardon me for going out of my walk … I take upon me to tell your Lordship that until Presbytery is drove out of His Majesty’s Dominions, Rebellion will ever continue, nor will that set ever submit to the laws of England.”

“In a time of greatest doubt and discouragement, Alline and his followers in every township pointed out the blessings of peace, and turned men’s thoughts away from the political issues of the day. The uncertain Nova Scotians were made to feel that in contrast with conditions in the other colonies their own lot was good, and that in escaping the horrors of war they had been the particular subjects of divine favor.”

Armstrong, Maurice Whitman, 1905-1967. The Great Awakening In Nova Scotia, 1776-1809. Hartford: American Society of Church History, 1948. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89065270951