“The Canadian colonies have always been deprived of representation in the Imperial government, and, until the recent Dominion Constitution, prescribed by act of the British Parliament in 1867, they had few privileges of self-government. The colonial government given to Canada after the fall of the French power was not even as liberal as that under which the New England colonies had struggled. The home government understood the peculiar nature of its subjects and established a strong and almost tyrannical colonial administration, while the Canadians were content to be ruled by a Governor and Council, since they knew no government better than that of Louis XV., and did not desire self government and legislation according to the constitutional system of a governor and two branches or houses. The several Colonial Secretaries who were appointed do not seem to have worked for the best interests of the colonies, since their terms of office were dependent upon the success of their party. Each secretary understood the peculiar policy pursued by his party toward Canadian affairs and made it his custom not to acquire a suitable knowledge of the needs of his people, but to study how he might retain his place and salary. Thus, while the leading features of the Canadian policy were changing often with party movements, the details of carrying out that policy were in the hands of irresponsible agents who sat in their high seats in England.

The government established by the Constitutional Act of 1791 did not avert the abuses and misgovernment which resulted from differences in party politics. The province was divided into Upper and Lower Canada with a separate legislature in each, composed of a Council and Assembly. The executive power was vested in a Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada and a Governor of Lower Canada, who had also a certain control over the Upper province. There was an Executive Council, composed of officers of the Crown, presiding over both provinces. These provinces were then, as now, essentially different in ethnical character and political knowledge. The colonies were satisfied for years afterward with the rule of England; but when the increased population became fused with English and American settlers, it began to feel its strength, and appreciating the rights conferred by the Constitution of 1791 to desire their substantial exercise and further extension. Dissatisfaction naturally commenced in Lower Canada, the most powerful and progressive of the six colonies, and spread to the others. The question of becoming independent often agitated the minds of the Canadians, and after the triumphs of the revolutionary principle in Europe during the ten years preceding 1840, the excitement of the people was strongly in favor of a government similar to that “composing the industrious, moral and prosperous confederations of the United States.” The Assembly of Lower Canada, in 1834, passed a set of resolutions, asking for a Legislative Council chosen by the people, instead of by the Crown, and the power of revising the constitution. They declared that by this measure the British Parliament “would preserve a friendly intercourse between Great Britain and this province, as her colony, as long as the tie between us shall continue, and as her ally whenever the course of events may change our relative position.”

The sentiment of the people as represented in the lower house became so strong for reform of existing government or entire independence, that they “Resolved, that the neighbouring states have a form of government very fit to prevent abuses of power, and very effective in repressing them ; that the reverse of this order of things has always prevailed in Canada under the present form of government; that there exists in the neighbouring states a stronger and more general attachment to the national institutions than in any other country, and that there exists also in those states a guarantee for the progressive advance of their political institutions toward perfection, in the revision of the same at short and determinate intervals, by conventions of the people, in order that they may without shock or violence be adapted to the actual state of things.” Not content with these bold, and, as the British thought, treasonable expressions, they added that ” the institutions of Great Britain are altogether different from our own,” and ” that the unanimous consent with which all American States have adopted and extended the elective system, shows that it is adapted to the wishes, manners, and social state of the inhabitants of this continent. These numerous petitions, complaints and demands for redress of grievances were caused by the desire of the French Canadians to keep alive their nationality, the influence of American agitators, and the conflict of the two races arising out of those land grants which we have already investigated, as well as those made to the British-American Land Company, which increased the influence of the mother country. It is not necessary to trace the history of this agitation onward through its various stages. The people demanded:

- An Elective Council.

- The repeal of the Tenures Act, and the act creating the British-American Land Company.

- Complete Parliamentary control over the whole of the lands belonging to the colony.

- Complete control over revenue and expenditures.

The clamor for an elective legislative body was made by the French element, which was opposed to the English, and desired authority over the immediate representatives of the Crown. The Assembly withheld the supplies, and there followed acts of disorder, causing the rebellion of 1837-8 for national independence which was soon put down by those who were loyal to England and desired her supremacy. The leader of the revolt was Louis Joseph Papineau an ambitious French Canadian of mild manners, but possessing a discontented mind filled with theories for the advancement of the people of his nationality. He thought that by causing the Canadians to revolt he might gain the independence of Canada, with himself as Dictator, after the manner of the revolutionary leaders of France. The constitution of Lower Canada was suspended, and Lord Durham, who was appointed to administer the provisionary government, made a report on the conditions and needs of the province in which he recommended the restrictions of the French language and the union of the British North American possesions because “it would enable the province to cooperate for all common purposes, and above all, it would form a great and powerful people, possessing the means of securing good and responsible government for itself, and which, under the protection of the British Empire, might in some measure, counterbalance the preponderous and increasing influence of the United States on the American continent.”

The result was a bill brought forward by Lord John Russel, during the session of 1839, providing for a new constitution. The debates that followed were interesting and important, and local and responsible government received full consideration. Lord John Russel did not want separation, but said that the interference of the Imperial Parliament in affairs of colonial government ought to be confined to extreme cases. Therefore, by the constitution of 1840, the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, which had been separate since 1791, were united, and a government established whereby England removed the management of local affairs from the combinations and agitations in home politics, and permitted Canada to approach nearer the ideal self-government system of Teutonic states. Representation was divided equally between the two provinces, although Lower Canada was more populous. Lord Syndenham, who came out as Governor, succeeded, during his short term of office, in counteracting the French-Canadian influence by procuring an Anglo-Canadian majority in both Houses of the Parliament of the united province. This caused a feeling of security for a time in the country, since legislation was toward securing titles to real property and the abolition of the feudal system. One of the most successful arguments to excite rebellion had been that the inhabitants would free themselves from seignioral dues. The political movements of the times succeeding, were the endeavors of the “Liberals” and “Conservatives” to get the upper hand, and of the Governors to please both elements of the population. The Liberals had in their party the French-Canadian faction, headed by Mr. Papineau, who had been conspicuous in the late rebellion. They frequently agitated the subject of annexation or independence, and were encouraged by American speculators and those who had strong democratic ideas. It was through their maneuvering that the Rebellion Losses Indemnity Bill was passed through both Houses and received, from Lord Elgin, his sanction and recommendation to the home government. Annexation associations were formed in a few places, but the movement was confined to no particular party. It was noticeable that persons of the most opposite political views on domestic questions forgot their differences and united in their advocacy of this great scheme. The annexation manifestoes were approved by many who thought that England’s policy at that time was in favor of getting rid of her colonies. The position taken by many of the leading London papers, for example, the Times, was such as to convey this impression. It is likely that some decisive action would have been taken but for the internal disturbances in the United States which preceded the Civil War. Opposed to the Annexationists was a strong party consisting of the Roman Catholic clergy, with their French-Canadian followers, and the Conservatives. The latter, after the passage of the Rebellion Losses Indemnity Bill, had banded themselves into a ” British American League,” which was loyal to England and instrumental in restoring peace and order. The Conservative party began to lose power, and there was a movement in all parties toward reform. That part of Canada known as the maritime provinces does not need as much attention in a constitutional history, inasmuch as it has not been subject to the French influence. It was originally Acadie, but in the year 1749 England colonized it and gave it the name Nova Scotia (–not exactly…), including the provinces of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. The latter was constituted a distinct province in 1770, and the former in 1784.

These provinces were colonized by English, Scotch and U. E. Loyalists, and, therefore, remained in sympathy with British institutions. Their government was more responsible than that of French Canada and freer from great internal dissensions. It was quite natural, therefore, that Nova Scotia should take the first step toward forming a confederation of the provinces on the plan of responsible government so often proposed in political crises. This province, with that of New Brunswick, urged the union, and there resulted a conference of delegates from all the provinces at Quebec, October 10th, 1865, in which was formed the foundation of the present constitution and government. The Fenian movement against Canada in June, 1866, did not arise from a desire for annexation, but was planned by the leader, O’Neil, and his American followers, through sympathy for Irish independence. Their intention was to injure England and help Ireland gain its freedom. The government of Canada soon restored peace ; the United States then, as in the subsequent raid of 1869 by the same leader, giving assistance. The British North American Act federally united the provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and made provisions for the admission of other parts of British North America. The province of Canada was divided into the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, having their territories co-extensive with the old provinces of Upper and Lower Canada. Provincial constitutions were given to these provinces according to the constitutions existing before the Union Act of 1840. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick retained the same boundaries and provincial constitutions. Before entering on the discussion of the constitution it would be well to speak of the provinces lately admitted into the Dominion of Canada.

Manitoba was part of the territory granted to the Hudson Bay Company by Charles II. In 1811 the Earl of Selkirk, who owned stock in the company, purchased a large tract of country covering what is now Manitoba, and established a colony of Scotch, which was unsuccessful. The company bought it back in 1835 and established a government with a Governor and Council. Legislation over Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territories was vested in the Dominion in 1868, when a provisional government was established, but owing to the consequent conflicting rights of the company and the government, a rebellion arose among the French [Metis] led by Louis Riel, which resulted in the immediate establishment and entrance into the Dominion, in 1870, of the province of Manitoba. Its government is vested in a Lieutenant-Governor and Executive Council, and a Legislative Assembly. The Saskatchewan rebellion, in 1882, also led by Louis Riel, caused the formation of the provisional districts of Assinboia, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Athabasca, of the Northwest Territories, with a Lieutenant Governor and Council. British Columbia was also a part of the Hudson Bay Company’s territory, but at the time of the “gold fever” of 1858, it received distinct territorial government. Vancouvers Island was united with it in 1860. In 1871 it entered the Dominion with a constitution consisting of a Lieutenant-Governor, an Executive Council and a Legislative Assembly. Prince Edward Island entered in 1873, and has a legislature consisting of a Lieutenant-Governor, a Legislative Council and an Assembly. The Canadian constitution is based upon the English, although in many respects it borrowed from the American.

The Imperial Parliament does not allow local jurisdiction over those matters which regard imperial interests and honor, but maintains a large amount of control over the Dominion government, especially by reserving to England the rights of appointing the Governor-general, of making treaties and of disallowing acts not affecting trade and commerce. The Dominion can alter its constitution only through the Imperial Parliament and not, as in the United States, through the ratification by three-fourths of the states, of amendments proposed by a convention called by Congress or proposed by two-thirds of both Houses of that body. The local self-government system is in many respects directly the reverse of that in the United States. The provinces possess only the power of legislating on those matters allowed by the Dominion constitution. The government at Washington, on the other hand, is limited in its functions under the constitution by the rights of the several states. Here we find the distinction between “states” and “provinces.”

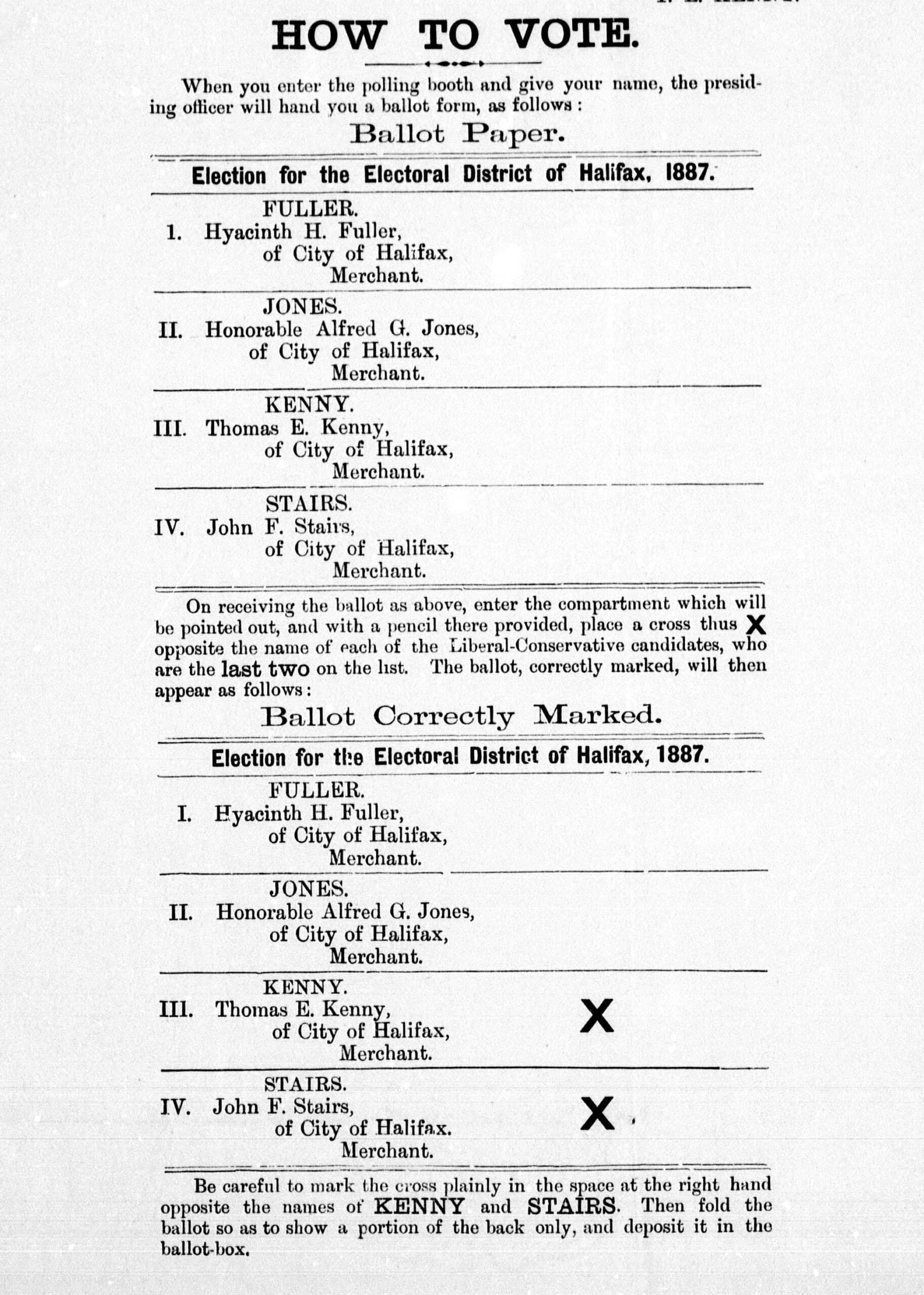

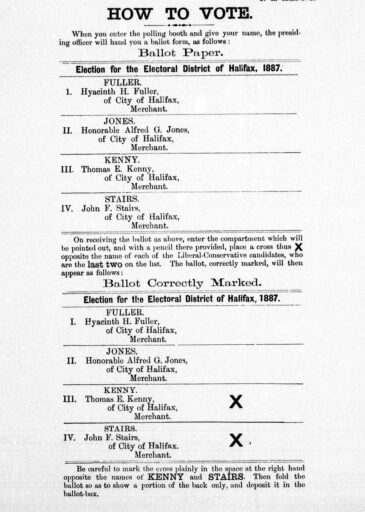

Imperial control in all matters can be traced to the fountainhead in the will of the sovereign prerogative. For the purpose of examining the constitution and comparing it with that of the United States let us glance briefly at the legislative powers, subject to the Imperial Parliament as embodied in the Governor General, Senate and House of Commons in the central government, and the legislatures in the provinces. The Governor-General, who represents the dignity of sovereignty is appointed by the Crown, and can be removed at pleasure. He appoints the member of the Senate from the provinces, and the Lieutenant- Generals. The members of the Senate hold office for life, and are of the aristocratic class. They therefore vote down all measures that may tend to diminish the power of the Crown or undermine their secure and lofty positions. The lack of real interest for local affairs in the provinces from which they are appointed gives them little support in the popular feeling, since their motives are not always for the best interest of the people. Canadian Senators do not fear the loss of votes at a re-election, and therefore do not have that incentive which spurs on the American Senator to advance the power of his state according to the idea of his constituents. The members of the House of Commons are chosen by the people and represent the true democratic ideas of government. Since 1885 the franchise in Canada has been uniform and based on ownership, occupation or income. The right to vote is given to all who possess the following qualifications:

- The ownership or occupation for at least one year of premises of the value of $300, in cities; $200 in towns, and $150 in other places.

- An income of $300 a year or an annuity of $100, provided there has existed a residence of one year.

- The father’s ownership or occupation, as required gives the franchise to the sons.

- Possession of fishing outfits to the value of $300.

This law regarding electors seems to be an improvement on the too liberal granting of the franchise practiced in many of our states. The government of Canada is in three branches, decidedly unlike the three powers in the United States, where there is a balance of power, each branch being able to veto the acts of the other two, and each receiving its authority from the people. Each state, in exercising those attributes not relegated to the central government under the federal constitution, is a commonwealth enjoying domestic sovereignty. By an admirable method adopted by the framers of the constitution the representation at Washington of states unequal in areas and populations is provided. The Senate is composed of two members from each state, who compose the Federal or Upper House, while in the Lower or National House the members are in proportion to the population of each state. In Canada, the Upper House and the Governor-General, though the latter is usually careful with his veto, work for the interests of the Crown, and the voice of the people can only be heard in the Lower House and the Privy Council of the Governor-General, according to the plan of responsible government.

There is no equality among the provinces; each is only a part of the whole Dominion. They are represented in the Senate as follows:

- Ontario, 24 members

- Quebec, 24

- Nova Scotia, 10

- New Brunswick, 10

- Manitoba, 3

- British Columbia, 3

- Prince Edward Island, 4

- Northwest Territories, 2.

The House of Commons consists of 215 members, representing the provinces as follows:

- Ontario, 92 members, representing a population of 20,904 to each.

- Quebec, 65 members, representing a population of 20,908 to each.

- Nova Scotia, 21 members representing a population of 20,979 to each.

- New Brunswick, 16 members, representing a population of 20,077 to each.

- Manitoba, 5 members, representing a population of 21,728 to each.

- British Columbia, 6 members, representing a population of 8,243 to each.

- Prince Edward Island, 6 members, representing a population of 18,148 to each.

- The Territories, 4 members, representing a population of 12,090 to each.

The number of 65 members for the province of Quebec was fixed, as it was thought that the population was of a permanent character, upon which the representation from the other provinces could be based. For each of the other provinces the members are in such proportion to the population, as ascertained every ten years, as the number 65 bears to the number of the population of Quebec. Thus it may be noticed that in the two provinces especially subject to the French and Catholic influence, the representation in the Dominion Parliament is greater than in the other provinces and sufficient to have a preponderating weight in all matters that come before it. The Queen has concurrent power over all matters within the legislative jurisdiction of the Dominion government, since she is not divested of her prerogative powers, and the Dominion government, in turn, over matters in the Provincial government. But within certain limits each legislature is supreme. The people of Canada are thus subject to the mother country through three legislative bodies. The lowest body is that of the province, headed by a Lieutenant Governor, whose acts can be vetoed by the higher bodies. England, therefore, has great power over Canada, for although she allows the government to regulate all matters between the provinces, as well as those pertaining to its own internal affairs, she will treat with the provinces only through the Dominion Parliament, which in turn must direct its communications to the Crown through the Colonial Office. If the present status of Canada should change, it is generally agreed upon that it will take one of these three destinies

- Imperial Federation.

- Independence and a new American Republic.

- Annexation to the United States.

Imperial Federation

The tendency of colonies has been to overcome their sense of inferiority by resenting the legal exercise of imperial powers. After attaining a mature growth, like the child become a man, they desire to leave the protection of the mother country and assume sovereign powers. To counteract this tendency, and secure a closer political union between England and her colonies, statesmen have long advocated a plan of Imperial Federation. By this system they propose to establish on a firm basis the relation which a dependency bears to the centre of power in the empire, and so define and regulate reciprocal obligations that distant and powerful colonies can be maintained as parts of one great empire. Thus, as the force of gravitation can hold the far off planets in subjection to the sun as the centre of one system, this Imperial Federation would unite states independent in their internal affairs into one great nation. A new body would be formed for imperial matters, and the colonies would enjoy independent legislative powers in all matters of self-government. The colonies would be on the same footing and free to act within the scope of their prescribed powers, but all subject to the decision of a common supreme tribunal. They would be immediately interested in all international affairs and have a power of voting on all such questions. War, therefore, could not be declared by England without the consent of her colonies, thus avoiding the often repeated complaint of colonies that they are compelled to assist in wars in which they have no interest. England could not impose taxes without their consent. Imperial rights would be exercised to maintain the unity of the empire, and promote the common interests of all its widespread possessions. There would be an universal military organization, and an universal commercial union establishing free trade between distant parts of the empire.

This theory of Imperial Federation is not one peculiar to modern colonial reformers, but is the outcome of ideas long cherished by those who believe in self-government. If we trace back through the events of colonial history of the United States, and examine carefully the charters granting lands in America, we shall see that the colonies enjoyed local autonomy subject to the sovereignty of the Crown. In the event of Imperial Federation the present colonies would tend to become sovereignties, and representatives in the federal congress would be partly ambassadorial. The representation from distant states with democratic ideas would tend to abolish the English hereditary nobility. Thus it is a question whether England would lose or gain power by this scheme. The advocates of this system belong to both parties in England, and for the purpose of discussing its practicability, are bound together in a society called the Federation League. Sir John Macdonald, the Premier of Canada, is a member, and has for his associates a wealthy class who think that by this method the annexation or independence of Canada would be retarded. The Marquis of Lome, in a work entitled “Imperial Federation,” says “Does not disintegration loom in the future, and is not the independence of Australia, and the annexation of Canada, a result sure to follow the local freedom practiced throughout the Anglo-Saxon Empire ?”

Independence

The recent growth of nations has been toward democracy. In former times the people never conceived the idea of a social condition different from that in which they were born, but as intelligence spread and knowledge became general, the principles of action in economics, education and religion advanced toward democracy. The people have gradually learned -that they are sovereign and constitute the state. Political independence, therefore, has raised itself from the relics of religious superstition and feudalism. Since the separation of the American colonies from the mother country in which Canada refused to join, struggling nations have turned to the example of the North American Republic for political reform. England may expect the separation of all her colonies. Her course in regard to them has been a beneficial one, but not made for ever.

The people of the colonies can move an overwhelming preponderance of power against existing institutions. They are thousands of miles from the mother country and almost independent in their self-government. Thus the only tie that binds is the military and diplomatic protection of England. Does Canada need this protection? The confederation has proved of great benefit to the country in creating an almost national existence, and was brought about by Canadian statesmen. It was a step toward Imperial Federation, since in all matters concerning their interests England consults Canada, and has appointed on such commissions, as that of the fisheries men who were especially interested in the promotion of Canadian affairs. Then, the idea of federation has been, in a small degree, carried out by Canada having a resident in London, known as High Commissioner, who acts in accordance with his instructions from the Dominion government. The first commissioner was Sir Alexander Gait, who was followed by Sir Charles Tupper. England has often assured Canada that she will protect its interests in the negotiations of all treaties, and has evinced a desire to retain only the treaty-making power. This, then, is intended as a link of connection whereby England, through honor and affection may continue her protection, at the same time allowing the Dominion Parliament almost sovereign powers. Canada has passed through the stages of development usual in all nations from the despotism under the old regime to the constitutional period, when the struggle between the monarch and the people took place, which led to the present self-government. It is but a short step forward to complete independence. Whether this will occur in the near future is a question which must be determined by the majority of the Canadian people, but political sentiment is divided between the Conservatives, Liberals and French Nationalists. The Conservatives are the old Canadians who still cling to the British flag, because under its protection they feel secure. They are the wealthier class of the population and compose the society immediately outside of the royal and aristocratic retinue attached to the Governor-General. He is the representative of royalty and in his person brings forcibly to the minds of the Conservatives their allegiance to the English Crown, which he represents. The Conservatives, headed by the old and beloved Premier, Sir John Macdonald, hold the most important offices, and therefore do not want the present condition of affairs disturbed. The Orangemen must also be classed in this party, although many of them since the allowance of the Jesuits’ Estates Bill have gone over to the Liberals. The Liberals comprise the “Young Canada” element of the population, and instead of being British colonists, would prefer to say: “We are Canadians” or possibly, “We are Americans.” There is no aristocracy in Canada that is regarded by the people as constituting their natural superiors and rulers, and the Liberals are asking the question

“Why not elect our own Governor and Senators?” Expressions are now frequently used which would have been regarded as high treason before the Union Act. The desire for independence or a national change has been admitted, even by those newspapers which work in the interest of the government. The London Free Press, the Windsor Review, the St. Catharine Star, the Toronto Mail and numerous other papers see indications of independence. Since the organization of a national party, whose motto was “Canada First,” the spirit of national independence has rapidly increased. The young Liberal Clubs in all parts of the Dominion are increasing their memberships even from the ranks of the Conservatives. The issue of independence has been frequently brought forward, and elections have taken place of candidates who were in favor of independence. There has been exhibited in Windsor, Ontario, a proposed Canadian flag of dark blue with a red square in the corner, in which is displayed a white beaver representing the Northwest territories, while in the blue field are seven stars representing the provinces.

The French Nationalists constitute a third and independent party, and side with that party in all political questions who will enable them to retain their ethnic and confessional autonomy. Those misunderstandings and differences which the inhabitants of Quebec have had so long with the Anglo-Canadians have not been dispelled by confederation. The growth of empire in the Northwest, and the ethnic influence which always existed in their favor among [Metis] has raised new hopes. They have long maintained a French Catholic province on an English Protestant continent, and hope ere long to see it promoted into a nation. The leading papers in Quebec have frequently expressed this desire of the French Canadians, and in a recent article La Verite says: “Let us say it boldly—the ideal of the ‘French Canadian people is not the ideal of the other races which today inhabit the land our fathers subdued for Christian civilization. Our ideal is the formation here, in this corner of the earth watered by the blood of our heroes, of a nation which shall perform on this continent, the part France has played so long in Europe. Our aspiration is to found a nation which, socially, shall profess the Catholic faith and speak the French language. That is not and cannot be the aspiration of the other races. To say, then, that all the groups which constitute confederation are animated by one and the same aspiration is to utter a sounding phrase without political or historical meaning. For us the present form of government is not and cannot be the last word of our national existence. It is merely a road toward the goal we have in view. Let us never lose sight of our national destiny; rather let us constantly prepare ourselves to fulfill it worthily at the hour decreed by Providence, which circumstances shall reveal to us.”

On the other hand, the Anglo-Canadians see that if they would establish a great nation they must abolish French institutions, the levying of tithes, and the maintenance of parochial schools by public money. These ethnic and religious differences retard the growth of independence and act as a drawback to annexation, for annexation is not likely to take place until after independence. Since Brazil has changed its government, and its de-facto existence has been acknowledged, British America is the only country on the hemisphere not a republic. England’s right to govern Canada is based wholly on the presumption that it is not able to govern itself. Is it not proper, then, that she should cease to play the part of a parent, by withdrawing that protection for which Ireland as well as Great Britain must pay? Her indirect liabilities through keeping the Canadian connection are enormous, since their commercial policies are at right angles, and England is prevented from entering into whatever relations she pleases with the United States. When Canada is free and exists under a policy of peace and free commerce it will be a matter of history as to her ultimate destiny. But we can only conjecture that, after the French influence has been over- come by an increased population, the greater nation will absorb the smaller on the North American continent.

Annexation

Although Canada is practically sovereign—a “semi-sovereignty”—it has not the power to discharge external functions, and is not a state in an international position. Therefore, in exercising power given by the constitution, whereby “new states may be admitted by the Congress into the Union,” it is necessary for us to consider our international relations with England. The methods by which annexation may be brought about are

- Conquest by the United States.

- Independence of Canada and cession of its territory by its people.

- Cession of Canada by its people with the consent of Parliament and the Crown.

- Treaty arrangement between Great Britain and the United States, and the consent of the Canadian people.

Behind the constitution there is a right to acquire territory by conquest, which is “an incident of sovereignty.” This is a power that has always existed, but in the present, development of international law and human rights, it is only exercised in the subjection of uncivilized people and semi-states. The interference of the United States in Canadian affairs would probably bring about a war with England, but other nations would not be likely to interfere in a movement in which they are not concerned, whereby the United States would prepare the way for that certain future advance in population and national prosperity. If it had been our policy to conquor, Canada would have belonged to the United States long ago, since statesmen have often referred to the advisability of annexation.

Mr. Clay, in a speech on the occupation of West Florida, said: “I am not, sir, in favor of cherishing the passion of conquest, but I must be permitted to conclude by declaring my hope to see, ere long, the New United States (if you will allow me the expression), embracing not only the old thirteen states but the entire country east of the Mississippi, including East Florida, and some of the territories to the north of us also.” It is the peculiar duty of a Republic to recognize the rights of other peoples, and so endeavor to maintain them. The second method is very simple, for as an independent state, Canada could rightfully cede her whole territory and unite her government with us without the interference of any foreign power. In treating the third method by which annexation might be accomplished, we must consider that Canada has not the power of making treaties with foreign states, which is an incident to sovereignty. But it might appoint a committee to treat with the United States, with the positive or tacit consent of the mother country, the conclusions of which might be accepted by the sovereign through a treaty.

This method would depend upon the willingness of England to permit Canada to go forth from her protection, and differs from the fourth method in the source from which the proposals for annexation seem to eminate. It is founded on the theory that the people constitute the state and that from them must proceed any desire for a change. The negotiation of treaties between sovereigns, is a usual method of annexation, as was demonstrated in the annexation of Schleswig-Holstein to Prussia, of the Neopolitan Provinces to Italy, and of Savoy and Nice to France. ̶I̶n̶ ̶a̶l̶l̶ ̶t̶h̶e̶s̶e̶ ̶c̶a̶s̶e̶s̶ The plebiscite of the people ̶w̶a̶s̶ should be obtained before the cession ̶s̶ is ̶w̶e̶r̶e̶ completed.

If England had the power to barter or give Canada without the will of the people, she might cede the territory to China or Russia; and thus a great social disturbance would occur through difference in unities. Whereas the United States is the only country to which Canada could properly be annexed. Now, as to the organization of the new government and relations. It would not be necessary to obtain the consent of each state in the Union for the admission of Canada, as long as there were a majority in Congress in favor of the union. This was demonstrated in the annexation of Texas. On the other hand, the Dominion could not cede the territory without the consent of the people of each province, for this would be a violation of the principle which we have just seen. For the same reason, England has been unable to join Newfoundland to the Dominion. Therefore, any province might declare its independence and unite its government with us; but it would be a violation of de jure rights under the Dominion, as the provinces have not sovereignty or the power to secede.

This has been clearly demonstrated by the uneasiness of Nova Scotia since confederation. This province was the first to propose the new government, but it soon desired to withdraw from a union with its undesirable neighbors—a procedure which it found impossible. Lately this desire for a change has clearly shown itself, nor would it be surprising if a proposition for annexation should come from this English province. The inhabitants of the ceded territory would be admitted according to the principle of our federal constitution, into all the rights of citizens of the United States. The rights and obligations which belonged to each province before the union would be binding upon them or the government at Washington. Thus the debt of Canada would be assumed by the federal government, apportioned among the provinces as it was before the Dominion Act, or divided according to relative population. The annexed territory would retain all its private rights of property in the soil, and the public buildings would belong to the province in which they are situated.

Having discussed the methods of annexation the next question is its practicability. On casting a retrospective eye on the progress of Canada we cannot but be struck with the difficulties it has had to encounter before attaining its present position on the threshold of a new existence. It is governed by institutions and laws similar to our own, and inhabited by a people, many of whom have a like origin, education and religion with ourselves. But we have seen differences between the populations which can only be gradually eliminated by social fusion. The question of religion in state and common schools would be a source of discussion and controversy, since we are apt to maintain our belief in non-sectarianism as a policy superior to that of Canada. We must not look to the provinces of Quebec, Ontario and those on the Atlantic, whose future can only be prophesied by the historic past, for a beneficial union with us, but to the wonderfully fertile and sparsely populated country extending to the Pacific. The west and northwest are receiving a tide of immigration which must, through similarity in ethnical character, develop social institutions suitable for an intimate alliance with us. The territory of the Dominion is contiguous, and annexation, if not necessary, would at least permit the extension of our commerce with perfect freedom and security. Its numerous harbors, large rivers and communications connect its people with our own, and, by the representative system and the avoidance of sectional prejudices and factions, the United States though of vast extent, might with perfect harmony and security expand into an entire North American Republic.”

Aitken, William Benford. “The Dominion of Canada; a study of annexation”, New York, H. K. Van Sielen, 1890. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gdc/scd0001.00173951760