Not just any old moldering title, but that of the second last royalist governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson. Written in 1765, at a time when all of the colonies were kindred, just previous to the implementation of the Stamp Act. Although specifically written on the history of Massachusetts, that Nova Scotia was once affixed ensures the inclusion of numerous details.

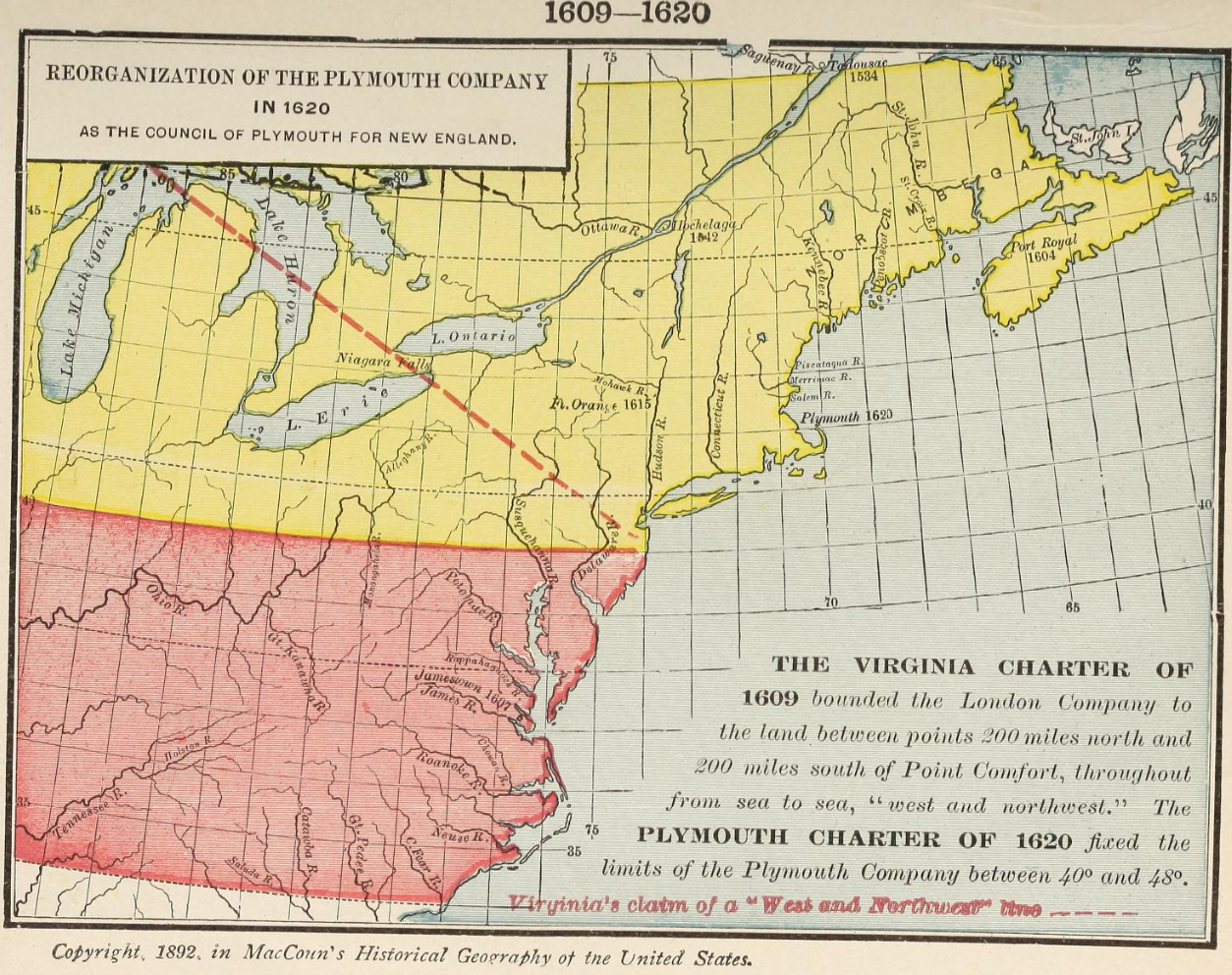

It is observable that all the colonies, before the reign of King Charles the second, Maryland excepted, settled a model of government for themselves. Virginia had been many years distracted under the government of presidents and governors, with councils in whose nomination or removal the people had no voice, until in the year 1620 a house of burgesses broke out in the colony; the King nor the grand council at home not having given any powers or directions for it.

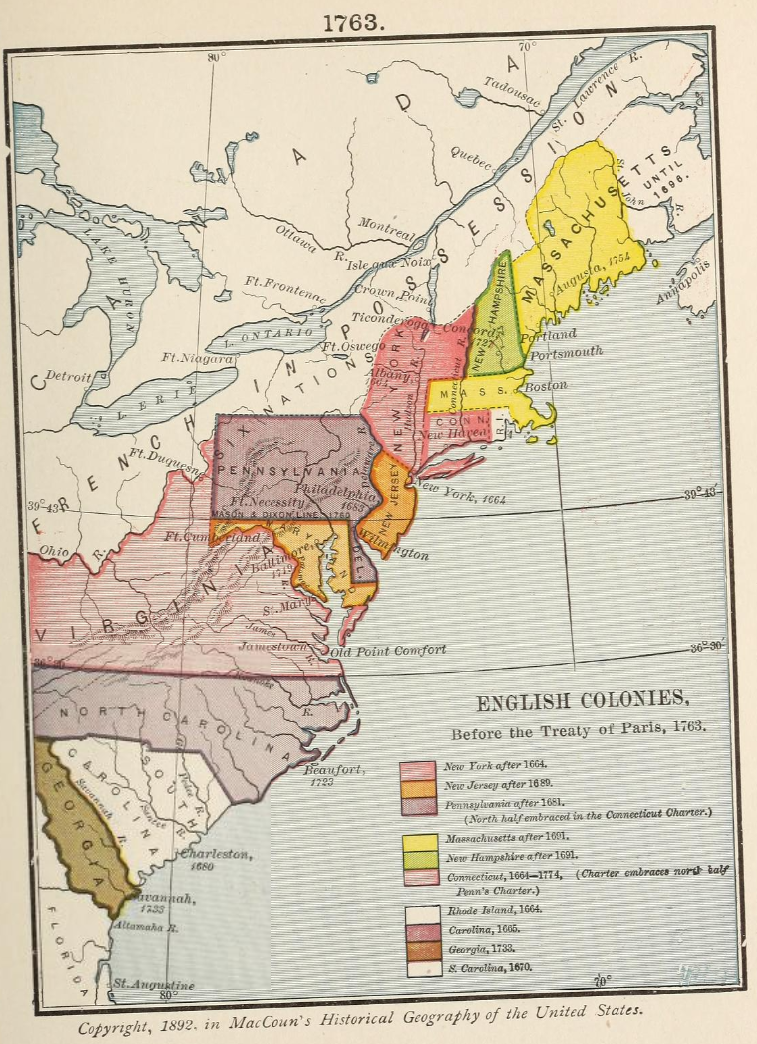

— The governor and assistants of the Massachusetts at first intended to rule the people, and, as we have observed, obtained their consent for it, but this lasted two or three years only; and although there is no colour for it in the charter, yet a house of deputies appeared suddenly, in 1634, to the surprize of the magistrates and the disappointment of their schemes for power. — Connecticut soon after followed the plan of the Massachusetts. — New-Haven, altho’ the people had the highest reverence for their leaders and for near 30 years in judicial proceeding submitted to the magistracy (it must however be remembered that it was annually elected) without a jury, yet in matters of legislation the people, from the beginning, would have their share by their representatives. — New Hampshire combined together under the same form with Massachusetts, — Lord Say tempts the principal men of the Massachusetts, to make them and their heirs nobles and absolute governors of a new colony; but, under this plan, they could find no people to follow them. — Barbadoes and the leeward islands, began in 1625, struggled under governors and councils and contending proprietors for about 20 years. Numbers suffered death by the arbitrary sentences of courts martial, or other acts of violence, as one side or the other happened to prevail. At length, in 1645, the assembly was called, and no reason given but this, viz. That, by the grant to the Earl of Carlisle, the inhabitants were to enjoy all the liberties, privileges and franchises of English subjects, and therefore, as it is also expressly mentioned in the grant, could not legally be bound or charged by any a without their own consent. This grant, in 1627, was made by Charles the first, a Prince not the most tender of the subjects liberties. After the restoration there is no instance of a colony settled without a representative of the people, nor any attempt to deprive the colonies of this privilege, except in the arbitrary reign of King James the second. The colonies, which are to be settled in the new acquired countries, have the fullest assurance, by his Majesty’s proclamation, that the same form of government shall be established there. Perhaps the same establishment in Canada, and the full privileges of British subjects conferred upon the French inhabitants there, might be the means of firmly attaching them to the British interest; and civil liberty tend also to deliver them by degrees from their religious slavery.

The inhabitants of Acadie or Nova-Scotia lived, above forty years after the reduction of Port Royal under the government of their priests. No form of civil government was established, and they had no more affection for England than for Russia. The military authority served as a watch to prevent confederacies or combinations. The people indeed chose more or less deputies from each canton or division, but their only business seems to have been to receive orders from the governor, and to present petitions to him from the people. Temporal offences, unless enormous, and all civil controversies were ordinarily adjudged and determined by their spiritual fathers. I asked some of the most sensible of the Acadians, what punishment’s the priests could inflict to answer the ends of government. They answered me by another question. What can be a greater punishment than the forfeiture of our salvation? In no part of the Romish church the blind persuasion, of the power of the priest to save or damn, was ever more firmly riveted; and although these Acadians have, for eight years past, been scattered through the English colonies, yet I never could hear of one apostate or so much as a wavering person among them all: and if the Canadians are treated in the same manner, they will probably remain under the same infatuation.”

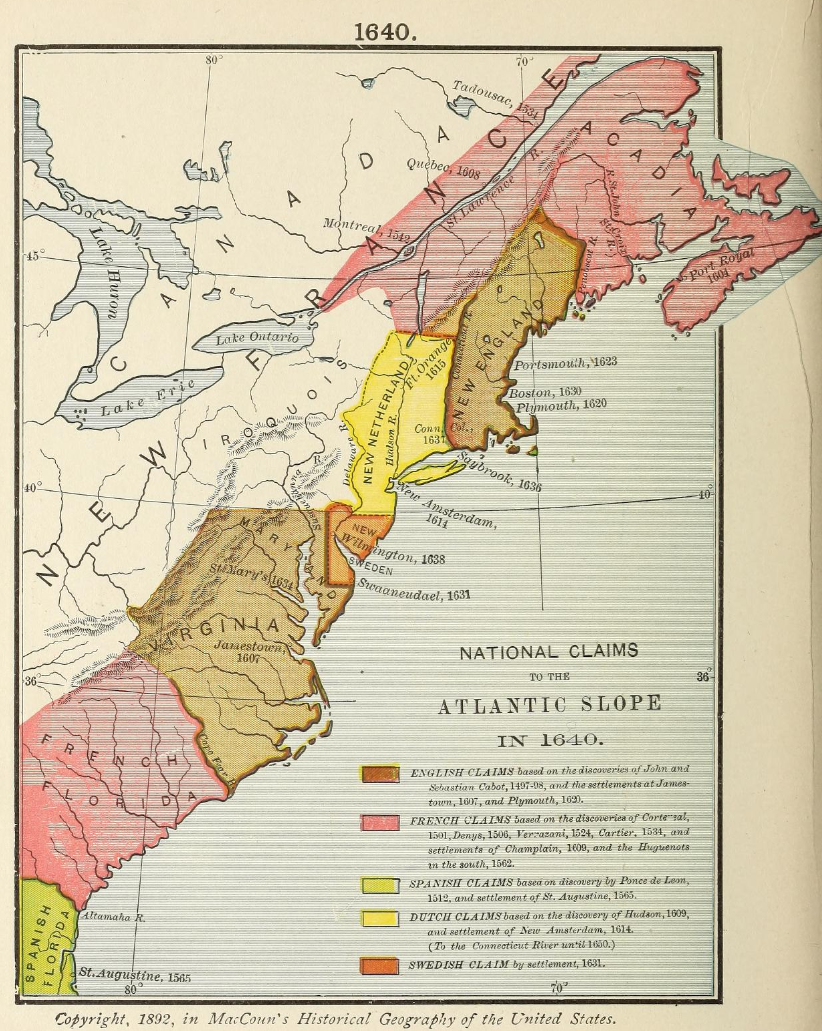

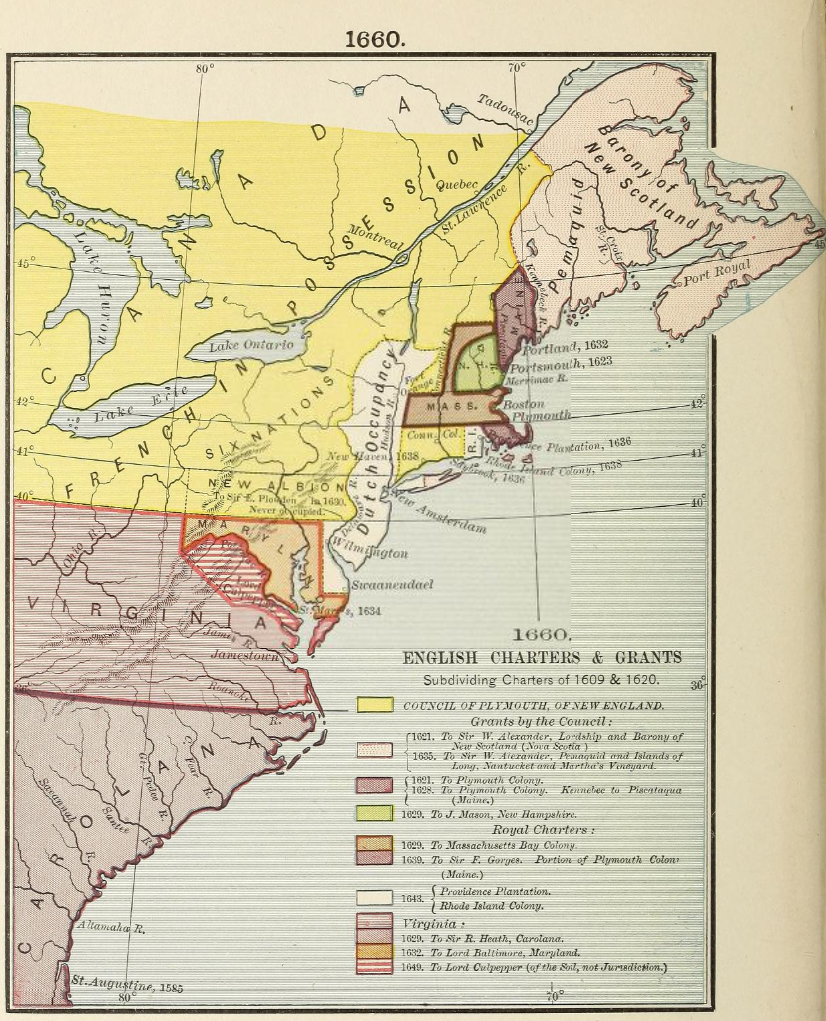

About this time [1644], much division and disturbance in the colony was occasioned by the French of Acadie and Nova-Scotia. It is necessary to look back upon the state of those countries. After Argall dispossessed the French in 1613, they seem to have been neglected both by English and French, until the grant to Sir William Alexander in 1621. That he made attempts and began settlements in Nova-Scotia has always been allowed, the particular voyages we have no account of. It appears from Champlain, that many French had joined with the English or Scotch, and adhered to their interest. Among the rest, La Tour was at Port Royal in 1630, where out of seventy Scots, thirty had died the winter before from their bad accommodations. La Tour, willing to be safe, let the title be in which it would, English or French, procured from the French King a grant of the river St. John, and five leagues above and five below, and ten leagues into the country; this was in 1627.

This appears from a list of the several grants made to La Tour, communicated to governor Pownall by Monsieur D’Entremont a very ancient French inhabitant of Acadie descended from La Tour, and who was removed to Boston in 1756 and died in a few years after. At the same time he was connected with the Scotch, and first obtained leave to improve lands and build within the territory, and then, about the year 1630, purchased Sir William Alexander’s title. La Tour’s title is said to have been confirmed to him under the great seal of Scotland, and that he obtained also a grant of a baronettage of Nova-Scotia. It is probable the case was not just as represented. King Charles in 1625 confirmed Alexander’s grant, under whom La Tour settled Penobscot, and all the country westward and southward, was at this time in the possession of the English. In 1632, La Tour obtained from the French King a grant of the river and bay of St. Croix and islands and lands adjacent, twelve leagues upon the sea and twenty leagues into the land. The French commissaries speak of this grant as made to Razilly.

By the treaty of St. Germains, the same year, Acadie was relinquished by the English, and La Tour became dependent upon the French alone. In 1634, he obtained a grant of the isle of Sables ; another of ten leagues upon the sea and ten into the land at La Have; another of Port Royal the fame extent; and the like at Menis, with all adjacent islands included in each grant. Razilly had the general command, who appointed Monsieur D’Aulney de Charnify his Lieutenant of that part of Acadie west of St. Croix, and La Tour of that east. In consequence of this division, D’Aulney came, as has been related, and dispossessed the English at Penobscot in the year 1635. Razilly died soon after, and D’Aulney and La Tour both claimed a general command of Acadie and made war upon one another. D’Aulney, by the French King’s letter to him in 1638, was ordered to confine himself to the coast of the Etechemins, which in all his writings he makes to be a part of Acadie. La Tour’s principal fort was at St. John’s. As their chief views were the trade with the natives, being so near together, there was a constant clashing of interest. In November 1641, La Tour sent Rochet, a protestant of Rochel, to Boston from St. John’s, with proposals for a free trade between the two colonies, and desiring assistance against D’Aulney; but not having sufficient credentials, the governor and council declined any treaty, and he returned. The next year, October 6, there came to Boston a shallop from La Tour, with his Lieutenant and 14 men, with letters full of compliment, desiring aid to remove D’Aulney from Penobscot, and renewing the proposal of a free trade. They returned without any assurance of what was principally desired, but some merchants of Boston sent a pinnace after them to trade with La Tour at the river St. John. They met with good encouragement, and brought letters to the governor, containing a large state of the controversy between D’Aulney and La Tour, but stopping at Pemaquid in their way home, they found D’Aulney upon a visit there, who wrote to the governor and sent him a printed copy of an arrêt he had obtained from France against La Tour, and threatened, that if any vessels came to La Tour he would make prize of them. The next summer (June 12) La Tour himself came to Boston, in a ship with 140 persons aboard, the matter and crew being protestants of Rochel. They took a pilot out of a Boston vessel at sea, and coming into the harbour saw a boat with Mr. Gibbon’s lady and family, who were going to his farm. One of the Frenchmen, who had been entertained at the house, knew her, and a boat being manned to invite her aboard, she fled to Governor’s island and the Frenchmen after her, where they found the governor and his family, who were all greatly surprized, as was the whole colony when they heard the news.

The town was so surprized, that they were all immediately in arms, and three shallops filled with armed men were lent to guard the governor home. Had it been an enemy, he might not only have secured the governor’s person, but taken possession of the castle opposite to the island, there not being a single man at that time to defend the place . This occasioned new regulations for the better security of the place. The castle was rebuilt in 1644, at the charge of the six neighbouring towns.

La Tour acquainted the governor, that this ship coming from France, with supplies for his fort, found it blocked up by D’Aulney his old enemy, and he was now come to Boston to pray aid to remove him. La Tour had cleared up his conduct, so as to obtain a permission under the hands of the Vice Admiral and Grand Prior, &c. for this ship to bring supplies to him, and in the permission he was stiled the King’s Lieutenant General in Acadie. He produced also letters from the agent of the company in France, advising him to look to himself and to guard against the designs of D’ Aulney. The governor called together such of the magistrates and deputies as were near the town, and laid before them La Tour’s request. They could not, consistent with the articles they had just agreed to with the other governments, grant aid without their advice; but they did not think it necessary to hinder any, who were willing to be hired, from aiding him, which he took very thankfully ; but some being displeased with these concessions, the governor called a second meeting, where, upon a more full debate, the first opinion was adhered to.

Some of the magistrates, deputies and elders, were much grieved at this proceeding. A remonstrance to the governor was drawn up and signed by Mr. Saltonstall, Mr. Bradstreet, and Mr. Symonds of the magistrates, and Mr. Nath. Ward, Ezekiel Rogers, Nathanael Rogers and John Norton of the elders ; wherein they condemn the proceeding, as impolitic and unjust, and set forth “that they should expose their trade to the ravages of D’AuIney, and perhaps the whole colony to the resentment of the French King, who would not be imposed upon by the distinction of permitting and commanding force to assist La Tour ; that they had no sufficient evidence of the justice of his cause, and in causa dubia bellum non est suscipiendum ; that La Tour was a papist attended by priests, friars. Sec. and that they were in the case of Jehoshaphat who joined with Ahab an idolater, which act was expressly condemned in scripture.

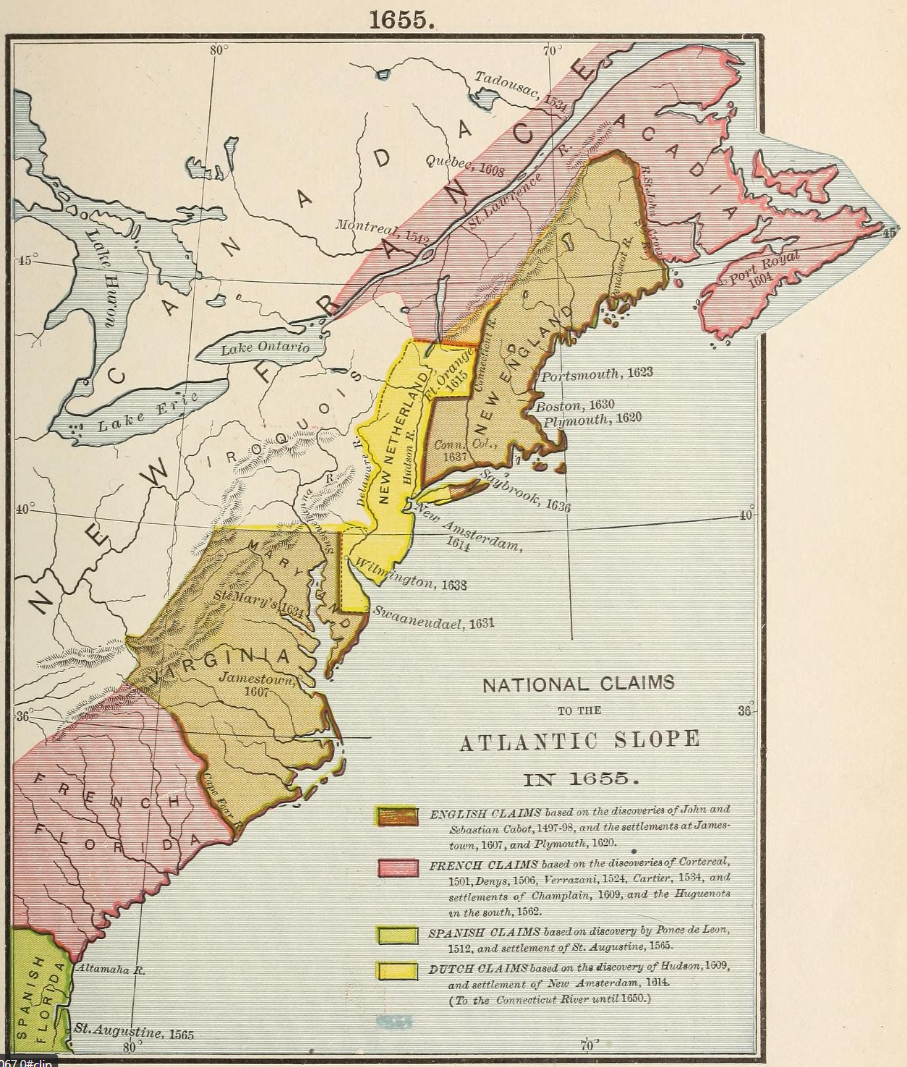

La Tour hired four ships of force, and took 70 or 80 volunteers into his pay, with which assistance he was safely landed at his fort, and D’Aulney fled to Penobscot, where he ran his vessels ashore; and although the commander of the ships refused to attack him, yet some of the soldiers joined with La Tour’s men in an assault upon some of D’Aulney’s men, who had intrenched themselves; but were obliged to betake themselves to flight, having three of their number slain. The ships returned in about two months, without any loss. The governor excused the proceeding to D’Aulney, as not having interested himself in the quarrel between them, but only permitted La Tour, in his distress, as the laws of Christianity and humanity required, to hire ships and men for his money, without any commission or authority derived from the government of the colony. D’Aulney went to France, and, being expected to return the next summer 1644, with a great force, La Tour came again to Boston, and went from thence to Mr. Endicot, who was then governor and lived at Salem, and who appointed a meeting of magistrates and ministers to consider his request. Most of the magistrates were of opinion that he ought to be relieved as a distressed neighbour, and in point of prudence, to prevent so dangerous an enemy as D’Aulney from strengthening himself in their neighbourhood; but it was finally agreed, that a letter should be wrote to D’Aulney, to enquire the reason of his having granted commissions to take their people, and to demand satisfaction for the wrong he had done to them and their confederates, in taking Penobscot, and in making prize of their men and goods at the Isle of Sables; at the same time intimating, that although these people who went the last year with La Tour, had no commission, yet if D’Aulney could make it appear they had done him any wrong (which they knew nothing of) satisfaction should be made ; and they expected he should call in all his commissions, and required his answer by the bearer. They likewise acquainted him, that their merchants had entered into a trade with La Tour, which they were resolved to support them in. La Tour being able to obtain nothing further, returned to his fort. Some of the province of Maine going this summer (1644) from Saco to trade with La Tour, or to get in their debts, put in at Penobscot in their way, and were detained prisoners a few days ; but for the fake of Mr. Shurt of Pemaquid, one of the company, who was well known to D’Aulney, they were released. La Tour afterwards prevailed upon Mr. Wanneston, another of the company, to attempt, with about twenty of La Tour’s men, to take Penobscot, for they heard the fort was weakly manned and in want of victuals. They went first to a farm house of D’Aulney ’s about six miles from the fort. They burned the the house and killed the cattle, but Wanneston being killed at the door, the rest of them came to Boston. In September, letters were received from D’Aulney informing that his master the King of France understanding that the aid allowed to La Tour, the last year, by the Massachusetts, was procured by means of a commission which he shewed from the Vice-Admiral of France, had given in charge that they should not be molested, but good correspondence should be kept with them and all the English, and that, as soon as he had settled some affairs, he intended to let them know what further com-mission he had, &c. Soon after, he lent a commissioner, supposed to be a friar, but dressed in lay habit, with ten men to attend him, with credentials and a commission under the great seal of France, and copy of some late proceedings again! La Tour, who was proscribed as a rebel and traitor, having fled out of France again against special order. The governor and magistrates urged much a reconciliation with La Tour, but to no purpose. La Tour pretended to be a Huguenot, or at least to think favourably of that religion, and this gave him a preference in the esteem of the colony to D’Aulney; but as D’Aulney seemed to be established in his authority, upon proposals being made by him of peace and friendship, the following articles were concluded upon, viz,. The agreement between John Endicott, Esq; governor of New-England, and the rest of the magistrates there, and Monsieur Marie commissioner of Monsieur D’Aulney, Knt. governor and lieut. general for his Majesty the King of France in Acadie, a province of New France, made and ratified at Boston in the Massachusetts aforesaid, October 8, 1644.

“The Governor and all the rest of the magistrates do promise to Mr. Marie, that they, and all the rest of the English within the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts, shall observe and keep firm peace with Monsieur D’Aulney, &C. and all the French under his command in Acadie. And likewise, the said M. Marie doth promise in the behalf of Monk D’Aulney, that he and all his people shall also keep firm peace with the governor and magistrates aforesaid, and with all the inhabitants of the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts aforesaid; and that it shall be lawful for all men, both the French and English to trade with each other , so that if any occasion of offence should happen, neither part shall attempt any thing against the other in any hostile manner, until the wrong be first declared and complained of, and due satisfaction not given. Provided always, the governor and magistrates aforesaid be not bound to restrain their merchants from trading with their ships with any persons, whether French or others, wheresoever they dwell. Provided also, that the full ratification and conclusion of this agreement be referred to the next meeting of the commissioners of the united colonies of New-England, for the continuation or abrogation, and in the mean time to remain firm and inviolable. This agreement freed the people from the fears they were under of ravages upon their small vassals and out plantations. La Tour was suffered to hire a vessel to carry a supply of provisions to his fort ; which vessel he took under his convoy and returned home.

The agreement made with D’Aulney was afterwards ratified by the commissioners of the united colonies, but he proved a very troublesome neighbor notwithstanding. In 1645 he made prize of a vessel, belonging to the merchants of Boston going to La Tour with provisions, and sent the men home (after he had stripped them of their cloaths and kept them ten days upon an island) in a small old boat, without either compass to steer by or gun to defend themselves. The governor and council dispatched away a vessel with letters to expostulate with him upon this action, complaining of it as a breach of the articles, and requiring satisfaction; but he wrote back in very high and lofty language, and threatened them with the effects of his master’s displeasure. They replied to D’Aulney, that they were not afraid of any thing he could do to them ; and as for his master, they knew he was a mighty prince, but they hoped he was just as well as mighty, and that he would not fall upon them without hearing their cause, and if he should do it, they had a God in whom to trust when all other help failed. With this ship D’Aulney made an attempt the same year upon La Tour’s fort while he was absent, having left only 50 men-in it; his lady bravely defended it, and D’Aulney returned disappointed and charged the Massachusetts with breach of covenant in entertaining, La Tour and sending home his lady. They excused themselves in a letter, by replying, that La Tour had hired three London ships which lay in the harbour. To this letter D’AuIney refused at first to return any answer, and refused to suffer the messenger, Capt. Allen, to come within his fort; but, at length, wrote in a high strain demanding satisfaction for his mill which had been burnt and threatening revenge. When the commissioners met in September, they agreed to send capt. Bridges to him, with the articles of peace ratified by them, and demanding a ratification from him under his own hand. D’Aulney entertained their messenger with courtesy and all the state he could, but refused to sign the articles, until the differences between them were composed ; and wrote back, that he perceived their drift was to gain time, whereas if their messengers had been furnished with power to have treated with him and concluded about their differences, he doubted not all might have been composed, for he stood more upon his honour than his interest, and he would sit still until the spring expecting their answer.

The general court, upon considering this answer, resolved to send the deputy governor Mr. Dudley, Major Demson and Capt. Hawthorn, with full powers to treat and determine, and wrote to D’AuIney, acquainting him with their resolution, and that they had agreed to the place he desired, viz. Penobscot or Pentagoet, and referred the time to him, provided it should be the month of September. This was opposed by some, as too great a condescension, and they would have had him come to the English settlement at Pemaquid; but his commission of lieutenant-general for the King or France was thought by others to carry so much dignity with it, that it would be no dishonour to the colony to go to his own home ; but it seems he was too good a husband to put himself to the expense of entertaining the messengers, and wrote in answer that he perceived they were now in earnest and desired peace, as he did also for his part, and he thought himself highly honored by their vote to send so many of their principal men to him; but desired he might spare them the labour, and he would fend two or three of his to Boston, in August following (1646) to hear and determine, &c. On the 20th of September, Messrs. Marie, Lewis, and D’Aulney’s secretary, arrived at Boston in a small pinnace, and it being Lord’s day, two officers were sent to receive them at the water side and to conduct them to their lodgings without any noise, and after the public worship was over, the governor sent Major Gibbons, with other gentlemen and a guard of musketeers to attend them to his house, where they were entertained. The next morning they began upon business, and every day dined in public, and were conduced morning and evening to and from the place of treaty with great ceremony. Great injuries were alleged on both sides, and after several days spent, an amnesty was agreed upon.

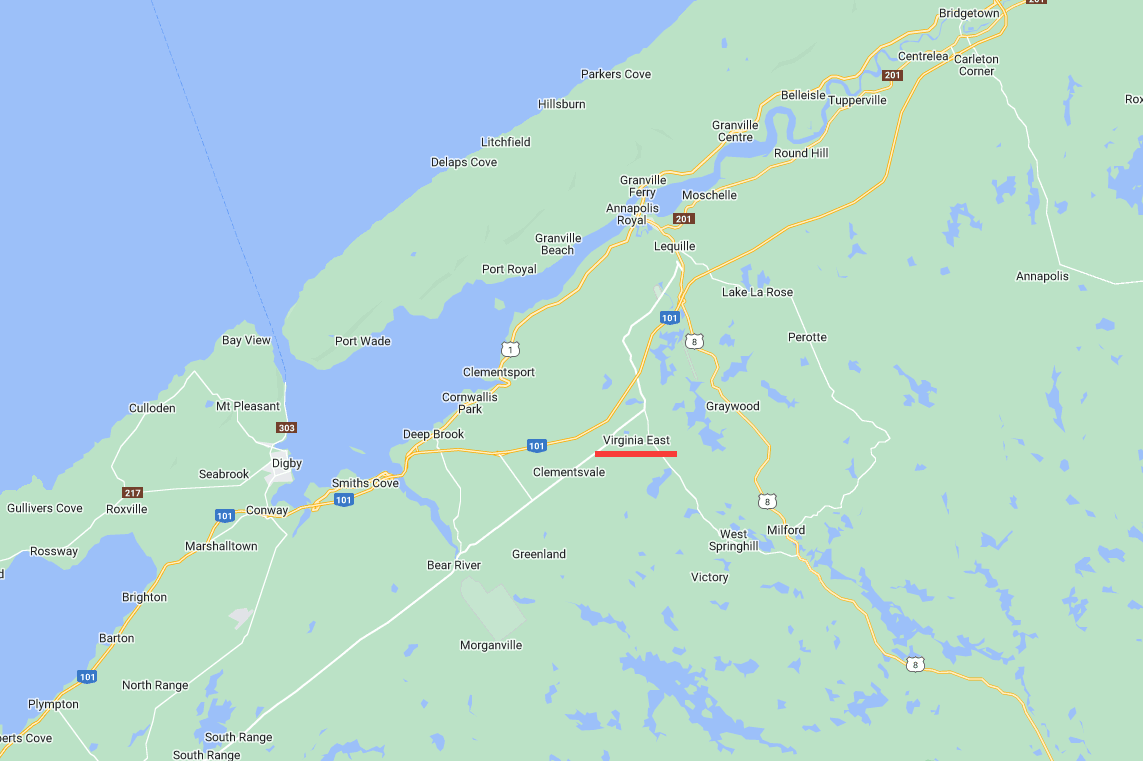

One Capt. Cromwell had taken in the West Indies a rich sedan made for the Vice Roy of Mexico, which he gave to Mr. Winthrop : This was sent as a present to D’Aulney, and well accepted by his commissioners, the treaty renewed, and all matters amicably settled. In the mean time, D’Aulney effectually answered his main purpose, for by his high language he kept the colony from assisting La Tour, took his fort from him, with ten thousand pounds sterling in furs and other merchandise, ordnance stores, plate, jewels, &c. to the great loss of the Massachusetts merchants, to one only of whom (Major Gibbons) La Tour was indebted 2500l. which was wholly lost. La Tour went to Newfoundland, where he hoped to be aided by Sir David Kirk, but was disappointed, and came from thence to Boston, where he prevailed upon some merchants to send him with four or five hundred pounds sterling in goods to trade with the Indians in the bay of Fundy. He dismissed the English, who were sent in the vessel, and never thought proper to return himself or render any account of his consignments. D’Aulney died before the year 1652, and La Tour married his widow, and repossessed himself, in whole or in part, of his former estate in Nova Scotia ; and in 1691, a daughter of D’Aulney and a canoness at St. Omers dying, made her brothers and fillers La Tours her general legatees. Under them, and by force of divers confirmations of former grants made by Lewis the 14th, between the peace of Ryswick and that of Utrecht, D’Entremant aforementioned claimed a great part of the province of Nova Scotia and of the country of Acadie. Of part of those in Nova Scotia he was possessed, when all the French inhabitants were removed by order of admiral Boscawen and general Lawrence.

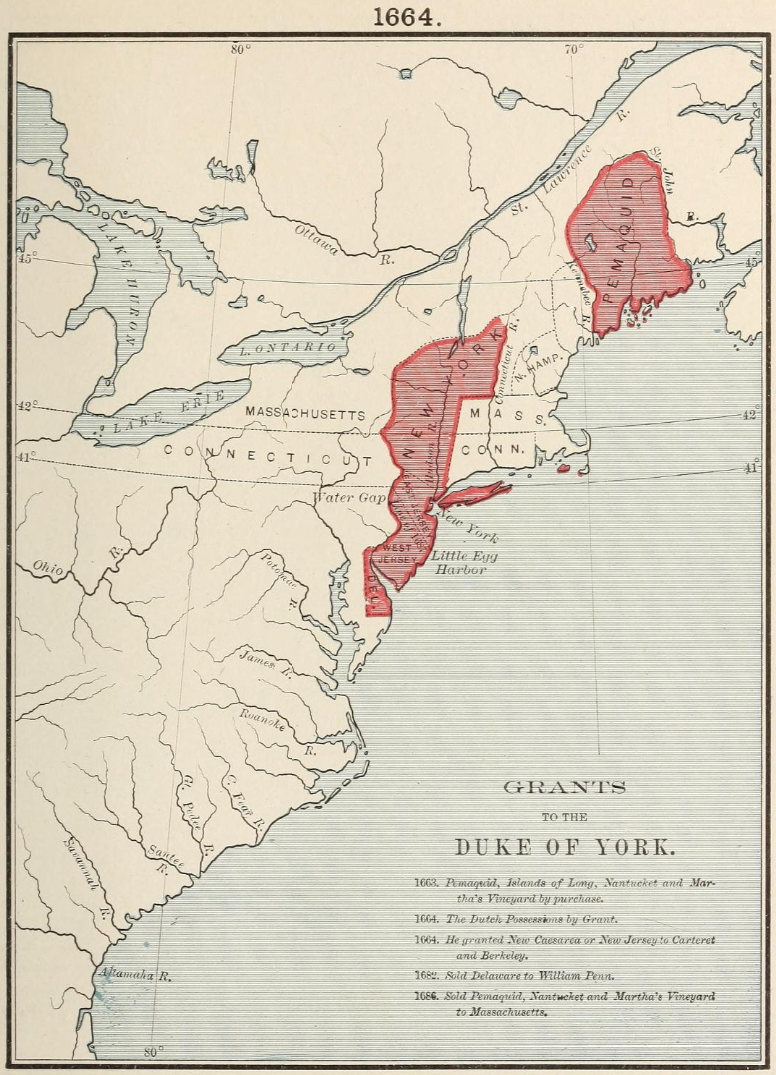

Sir Thomas Temple came first to New-England in 1657, having, with others, obtained from Oliver a grant of lands in Acadie or Nova Scotia, of which he was made Governor. He was recommended by Nathaniel Fiennes, son to Lord Say. Mr. Fiennes calls him his near kinsman. The King having recommended, by a letter Feb. 22d 1665, to the governor and council, an expedition against Canada, the court in their answer to Lord Arlington, July 17th 1666, say that “having consulted with Sir Thomas Temple, governor of Nova Scotia, and with the governor of Connecticut (Mr. Winthrop, who had lately been in England) they concluded it was not feazable at present, as well in respect of the difficulty, if not impossibility of a land march over the rocky mountains, and howling deserts, about four hundred miles, as the strength of the French there, according to reports.

From 1666 to 1670 Mr. Bellingham was annually chosen governor, and Mr. Willoughby deputy governor. Nova-Scotia and the rest of Acadie, which had been rescued from the French by Cromwell, were restored by the treaty of Breda. The French made little progress in settling this country. The only inconvenience the Massachusetts complained of, until after the revolution, was the encouragement given to the Indians to make their inroads upon the frontiers. Sir Thomas Temple who, with others had a grant of the country first from Cromwell, and afterwards from King Charles, thought he had reason to complain, and the King’s order was repeated to him, to give up his forts to the French, some pretense being made for not complying with the first order.

Hutchinson, Thomas. The History of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay. 1765. https://archive.org/details/historyofcolonyo00hutc/page/94/mode/2up