From The Story of Dartmouth, by John P. Martin:

Dartmouth, long before the European explorers and colonizing forces, had a 7,000 year history of occupation by the [Mi’kmaq]. The [Mi’kmaq] annual cycle of seasonal movement; living in dispersed interior camps during the winter, and larger coastal communities during the summer; meant there were no permanent communities in the Euro-centric sense, but Dartmouth was clearly a place frequented by [Mi’kmaq] for a very long time. Whether it was the Springtime smelt spawning in March; the harvesting of spawning herring, gathering eggs and hunting geese in April; the Summer months when the sea provided cod and shellfish, and coastal breezes that provided relief from irritants like blackflies and mosquitos, or during the autumn and its eel season; Dartmouth with its lakes and rivers, both breadbasket and transport route back and forth to the interior, was a natural place for the [Mi’kmaq] to spend their non-winter months.

A fascinating look into what Nova Scotia and Atlantic Canada could’ve looked like, from the end of the ice age at 19,000 BCE, until present. By 12,000 BCE, this model shows Cape Cod extending much further into the ocean than it does at present, along what is now Brown’s bank, a ridge which more or less stretches all the way to Sable Island along the continental shelf. A sea level 300 feet lower than it is today was enough to create a kind of land bridge to the parts of western and central Nova Scotia no longer under ice, the Bay of Fundy looking like it was an inshore repository for glacial meltwater until sea levels rose. This could’ve allowed for human exploration and settlement in what is now known as Nova Scotia previous to the retreat of the ice sheet in full.

By 10,000 BCE most of the ice had retreated, which squares with the earliest artifacts found in the area, such as at Debert, which date to the same general period, if not previous to that. That sea levels had risen one hundred feet in this two thousand year period might be instructive as to why artifacts are few and far between from this period, many of the settlements, if coastal, would have long ago been lost to the sea. Assuming the artifacts found (at Debert and Belmont) were not from nomadic hunters, and that this model is somewhat accurate, Nova Scotia could have been settled for 10,000 years or more.

Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20210807155606/https://sos.noaa.gov/catalog/datasets/blue-marble-sea-level-ice-and-vegetation-changes-19000bc-10000ad/, https://web.archive.org/web/20130219202242/https://sos.noaa.gov/Docs/bluemarble3000h.kmz

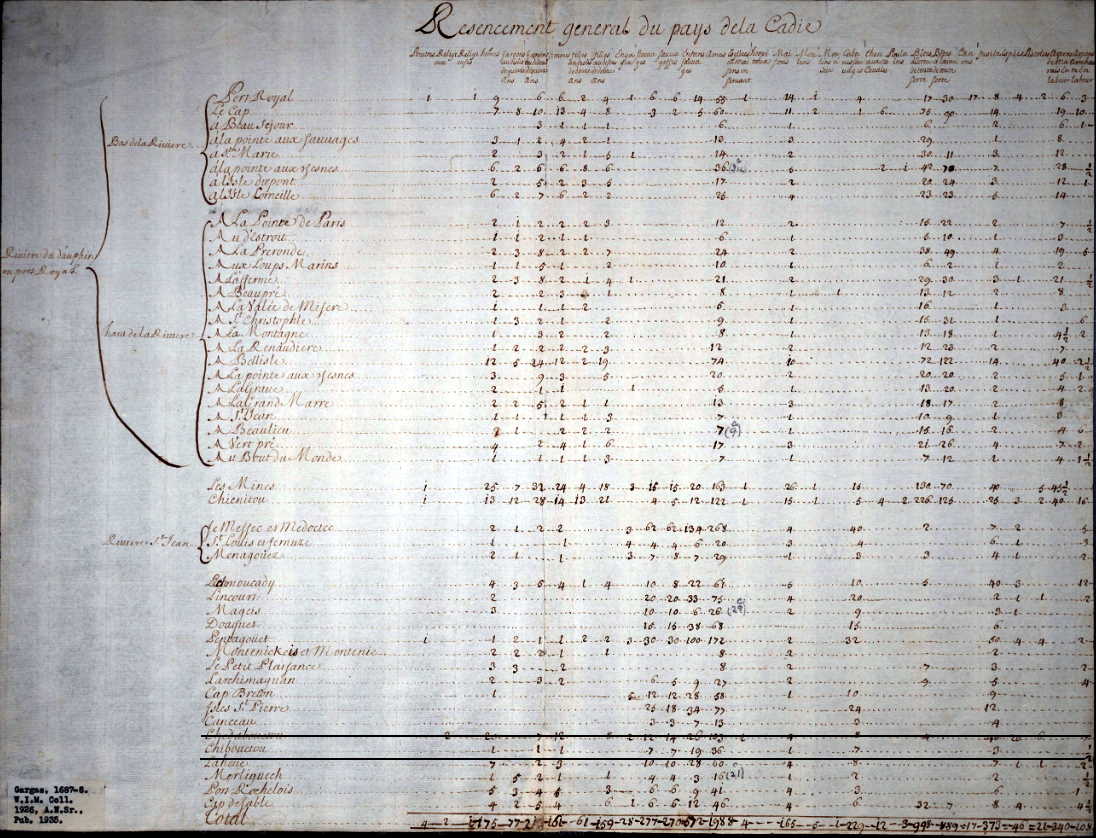

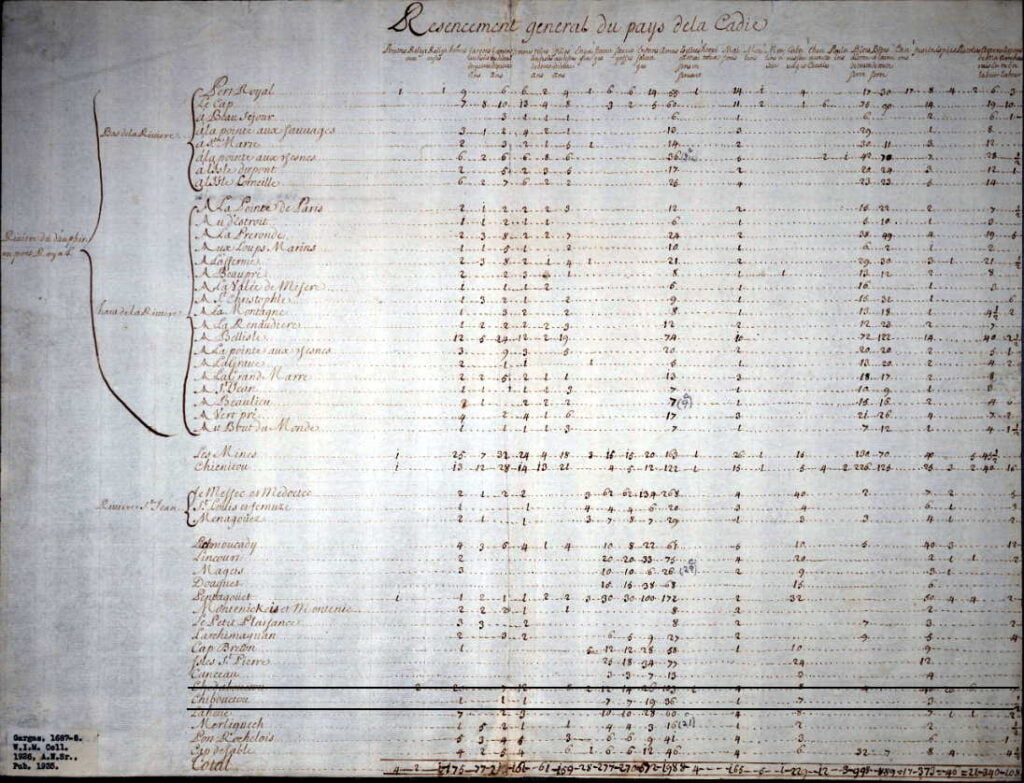

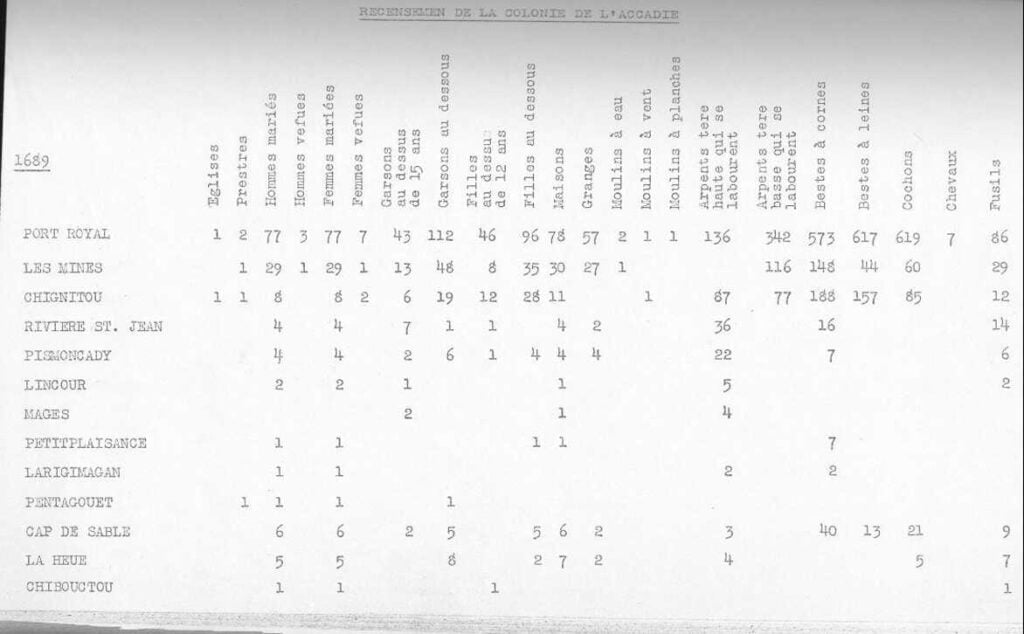

A census of the district of Acadia taken in 1687-1688 attributed to de Gargas shows Chebucto had 1 French family consisting of a man, wife and son; that there were 7 Mi’kmaw men, 7 Mi’kmaw women and 19 Mi’kmaw children, “36 souls” in total. 1 French house, 7 Mi’kmaw homes, 3 guns, 1/2 acre of improved land.

The St. Malo fishermen who were located at Sambro and at Prospect in the days of French ownership, must often have run to the inner harbor either to dry fish on our long beaches, or to barter furs with the natives who were always their allies. On the Dartmouth side of the harbor, geographical conditions were far more favorable for congregating, with three voluminous streams of never-failing fresh water flowing down to the estuaries of the two little bays, both later known as Mill Cove.

Besides that, there was an abundance of shell fish available at low tide, along with lobsters, crabs, sea-trout, salmon, halibut, codfish, and haddock, with the usual runs of herring and mackerel in warm weather. The woods teemed with wild life. Partridge roosted on trees, moose and deer roamed the forest, and wedges of wild fowl honked high overhead.

The evidence already submitted that the [Mi’kmaq] resorted to the Cove, is borne out by the description of Cobequid (Truro district) by Paul Mascarene about 1721, where he states that “there is communication by a river from Cobequid to Chebucto”. This Implies that the Shubenacadie route had long been in use. Engineer Cowie, after studying several harbor sites for Ocean Terminals a hundred years ago was of the opinion that Chebucto had been used as a trading post over a century before its permanent settlement.

In 1701, when M. Brouillan the newly appointed French Governor, came here from Newfoundland to rule Acadia, he went overland from Chebucto to Port Royal. This is in Murdoch’s History. Dr. Thomas H. Raddall, in his bicentennial story of Halifax, thinks that on this occasion, [Mi’kmaq] transported the Governor by the well-known canoe route of Dartmouth Lakes. (One can’t imagine a viceregal party trudging over a rough black-flied trail from Bedford to Windsor, or portaging through the shallow rivers of that section of country).

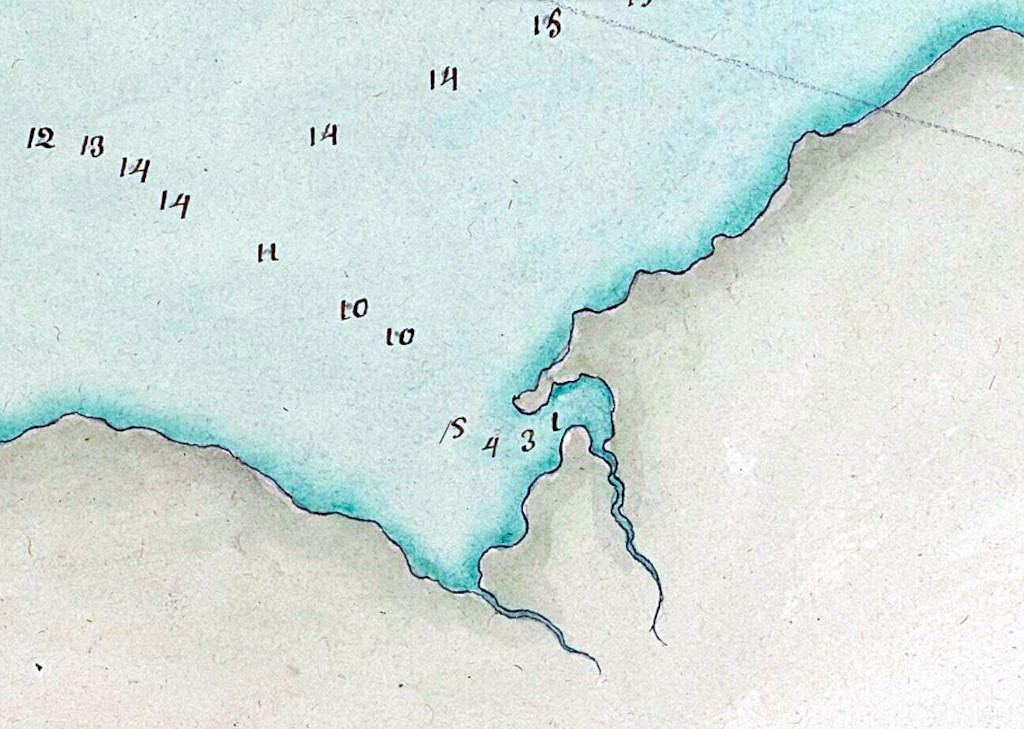

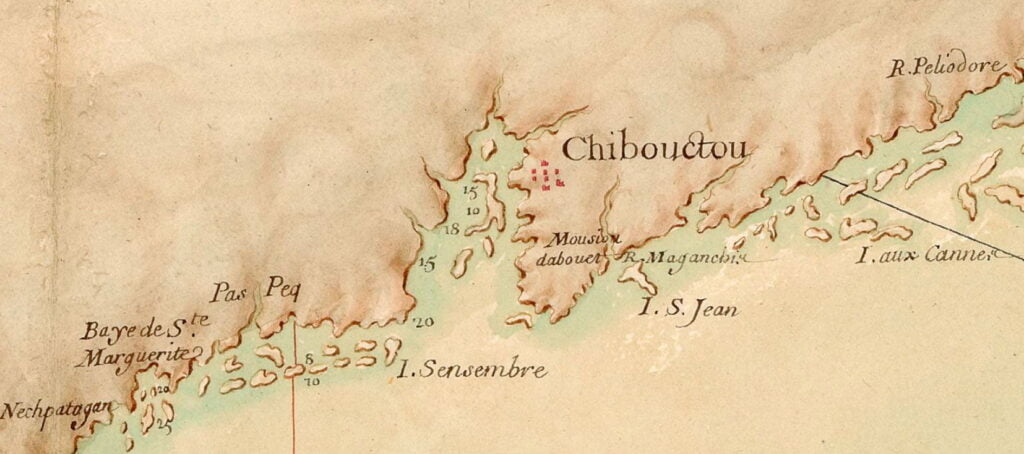

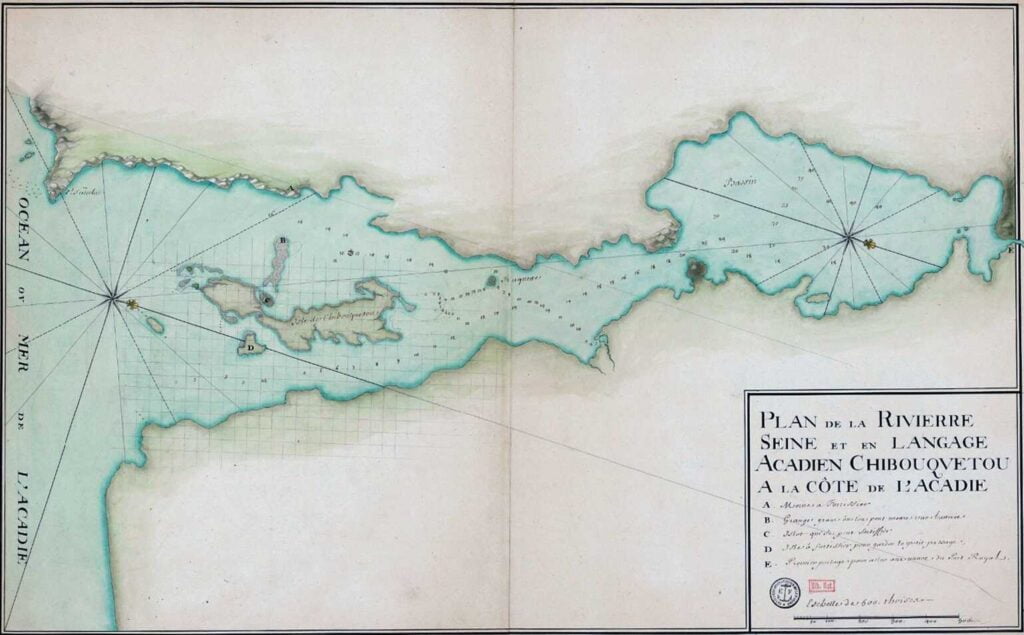

One of the early sketches of Dartmouth side is preserved at the N.S. Archives. It is a detailed drawing of the whole shore and harbor, showing the depth of water from the Eastern Passage to the head of the Basin, done by the French military engineer De Labat in 1711.

The indentations of the various inlets seem quite accurate. The soundings must have occupied a full summer, and the work was no doubt done from small boats; otherwise his large vessel would have butted such shoals as Shipyard Point and the one off shore at Queen Street.

Not sure whether this is the 1711 map Martin attributes to De Labat but it is detailed, especially as it relates to the Dartmouth Cove, and it contains a number of soundings as he describes. From: “Plan de la rivière de Seine et en langage accadien Chibouquetou” http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53089940v/f1.item.r=halifax.zoom